The original exercise taken from The Choreographer’s Way by Jonathan Burrows is “Try to make a piece only using your habits” (Burrows 2010). My first adaptation is as follows:

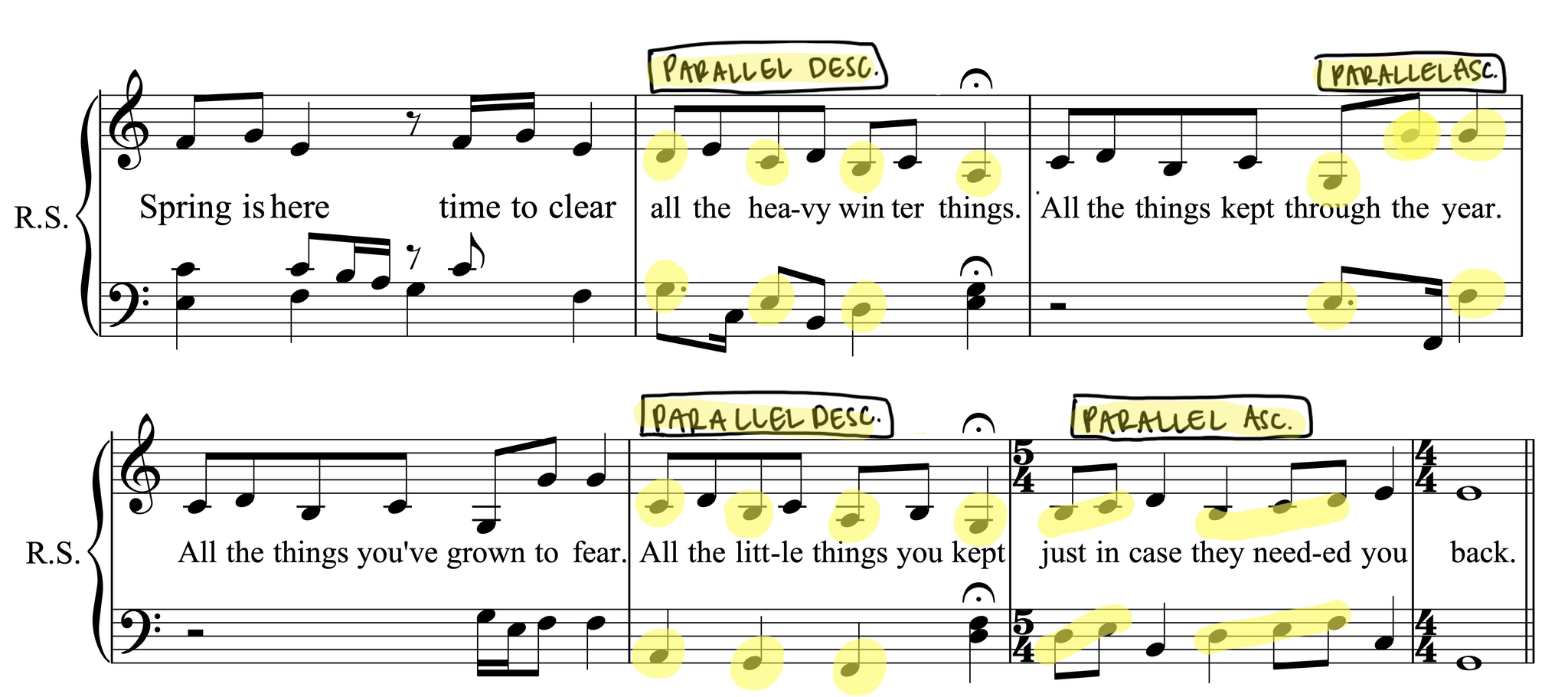

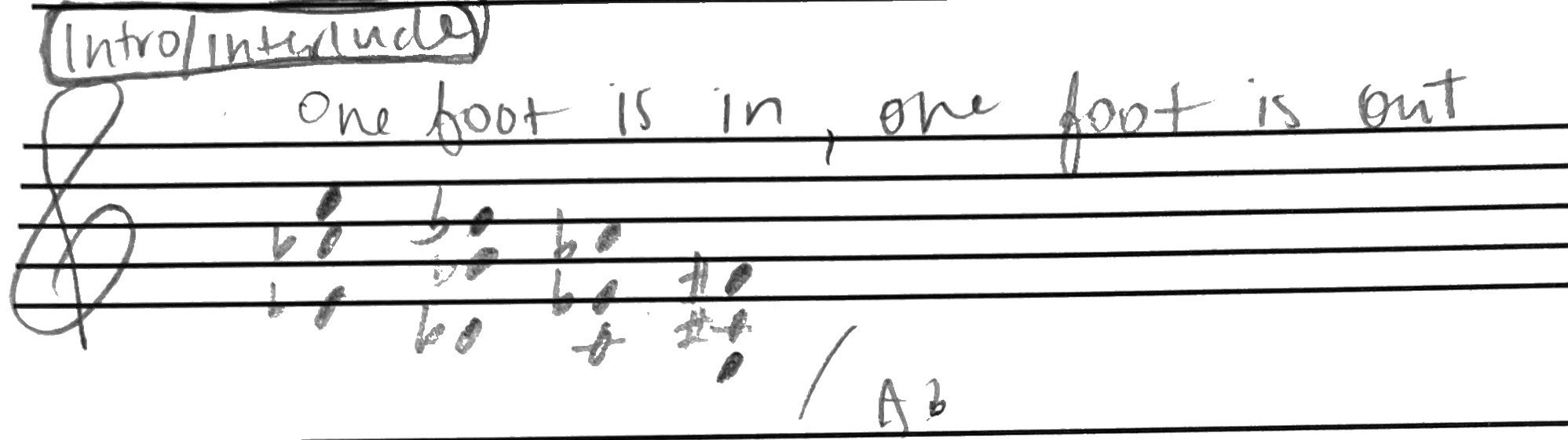

When I started composing “Spring Cleaning,” I had the habit of parallel major chords and parallel motion between the melody and harmony in my head. The first parallelism between the melody and harmony occurs in the second measure. The bassline descends first with a minor third then in steps for the downbeat of each group over the course of three beats. The eighth note melody also descends in steps on the downbeat. This parallelism continues in the third and fourth beats of measure three (the melodic intervals are different but the melody and bass both ascend). In measure five, there is a similar figure to measure two, starting on a different bass note and descending in steps until beat four.

In measure six, it continues with parallel ascending notes on beats one, three, and four. Despite intending to write with parallel major chords, there are few examples of this. In actuality, I mostly alternated between major and minor triads in different inversions. On the topic of habits, I started writing lyrics related to personal introspection and letting go of old things mentally. This lyric theme was not intended by the method instructions, it just happened. At this point, I decided to develop this idea and realized it would be impossible to continue only using habits, so I strayed from the rules of the exercise. I used what I wrote as a rubato first section. I continued from there with a wordless slow grooving melody as a second section which progresses into a third section of a soli over a two-chord vamp. The structure then goes back to the wordless melody (in a new key), and the rubato section, making it a symmetrical composition.

Results Attempt 1:

I only came up with one main idea that suited my tastes throughout my time testing this version of the method. I had some other starts and ideas but nothing interesting enough for me to develop. The song that I composed is one of my most unique songs in structure and a new favorite in my repertoire. I think this is because after I started the piece, I soon gave up on the exercise entirely and just completed it how I wanted to with no restrictions. In this way, I failed in my use of this method but this failure produced a composition that I am excited about. Although my research is aimed at finding usable methods for inspiring composition, by rebelling against the method, I made music I like. So, in many ways, I consider it a success.

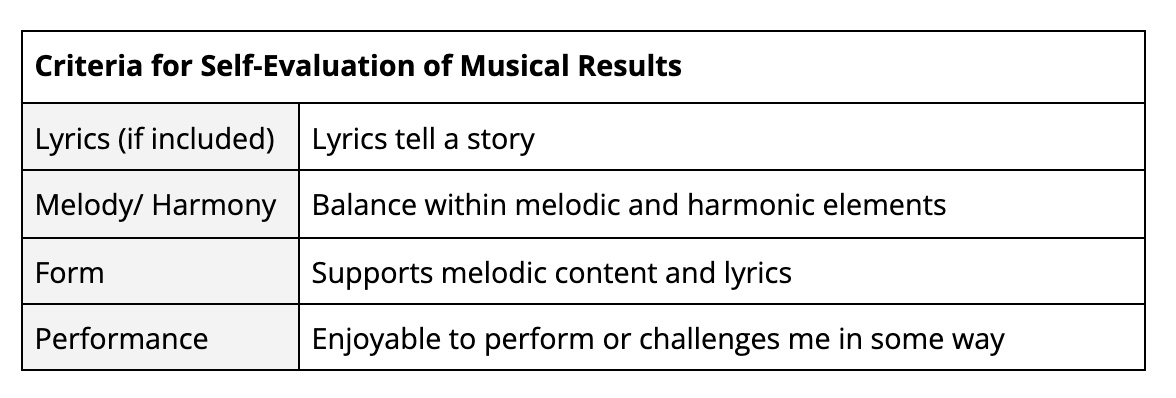

Melody/Harmony: There is balance in the opposition between the diatonic and non-diatonic in the melody and harmony of this composition. The rubato sections are primarily diatonic in melody and harmony whereas the wordless groove section is mostly non-diatonic harmony and melody. The soli section is a balance of the two with a diatonic and repeating harmony of D13(sus4) to Cmaj7 and a melody that explores both diatonic and non-diatonic possibilities on top of the progression.

Form: The three-part symmetrical form (rubato section, groove section, soli, groove section, rubato section) supports a build through the soli section to a recapitulation of the groove section as the apex of emotion. Lastly, the repeat of the rubato section at the beginning and ending allows for a clear difference in the meaning of the lyrics.

Performance: I enjoy performing this song because of how personal and exposed it is. The phrasing and timing of the counterpoint section is challenging for delivering the lyrics and the timing is different each time I perform it.

In my journal, I wrote:

“To start off this week I made a list of my habits just based on tools that I tend to use regularly or things I use when I get stuck composing. I only came up with 5 things that I think are pretty consistent throughout my writing. I found it was hard to stick with only using my habits. Maybe this is because I only identified 5 to start but I felt like I was choosing 1 to focus on and then creating connecting material to another one. It was difficult and didn’t really suit my tastes to do some of them at the same time or in close proximity.”

Reflection: Although I was very excited to try this method, I found that trying the exercise in this way was unsuccessful for me. I felt too stifled by the idea of only writing a song completely made from habits. This could result from not identifying enough habits or identifying mostly harmonic habits and fewer melodic or rhythmic habits. Additionally, when I analyzed my songs for habits, I looked at some that I had created since starting my research. I think I should not have included these since I wrote them using different methods that may involve certain specific habits of their own.

Some problems with this attempt:

-

The habits do not necessarily work simultaneously/ they can be mutually exclusive.

-

The timing of when each habit occurs/when to use it is unclear, therefore it is hard to use as a guideline.

-

Some habits are only used in certain situations so, in order to use them, one would have to create the situation that needs that habit.

-

Using only habits for the whole composition is such a strict guideline that, even though restriction can positively promote creativity, felt too restrictive for me.

-

The method could be unapproachable for people without knowledge of theoretical analysis.

-

It would be impossible for people new to composition as they would not have habits formed.

-

I used habits from compositions I have made since starting my research.

-

I could have done a more thorough analysis of songs beforehand.

After this reflection, I updated and adapted the method to reflect the observations from my first attempt. I liked my process of making a list of my habits so, I kept this as part of the exercise. Then I made the exercise more specific by focusing on one habit only.

When reading the text surrounding the exercise in The Choreographer’s Handbook, I found more clarity on the desired outcomes of the exercise. Burrows states, “the paradox is that when I accept that all I can do is the old ideas, the habits, then I relax, and when I relax then without thinking I do something new” (Burrows 2010). Based on this quote, I tried to keep the intention of acceptance in the exercise by focusing on featuring a habit. I believe the exercise is meant to first, push one to be aware of one’s habits while creating, and subsequently, guide one to accept these habits as something positive rather than something to hide or change. In this way, even though the piece is not necessarily fully formed by habits, by featuring the habit in the composition, one must accept its presence and may therefore come up with other ways to incorporate and conceptualize it.

Case study, “Waste No More Days”

In my reanalysis of my previous compositions, I found the recurring habit of using anaphora in my lyrics. Anaphora is “the repetition of words or phrases in a group of sentences, clauses, or poetic lines” (Malewitz 2023). I specifically used them at the start of a new musical section. I selected this habit and thought about how to emphasize it. I came up with the idea of making it a standalone musical section that recurs throughout the song. Additionally, I harmonized underneath the melody to emphasize this section and the lyrics even more. My original sketch of this section can be seen to the right.

Now that I had a recurring element for the song, I started writing a framework to place the element into. In these sections, I did not focus on writing using any identified habits. As noted in my journal, I enjoyed this freedom. The recurring section gave a direction for the rest of the song: high energy, sassy, and strong. Because the lyrics for this first section are ambiguous, it was clear to me that the next sections would need to provide more context to the story. With these directions from the first four bars, I wrote three contrasting sections, a section of bass groove with a simple melody to tell the story (section II), another section with more harmony and longer notes/phrases to provide rest from the drive of the other two sections (section III) and a five bar hook (section IV).

Melody/Harmony: There is balance in the harmonic tension and release of this composition. Section II is centered around Bmin7 and feels stable. Then, section I adds tension by placing upper structure triads over Ab and Gb in the bass. The first eight bars of section III have the typical tension and release of jazz harmony through a (substituted) ii-V-I progression. This is extended with very diatonic and stable harmony around the key center of D for eight bars of a release. Lastly, there is the section of five bars that builds up the tension and energy with a progression of non-diatonic chords with a fast harmonic rhythm to B minor.

Form: The order of the different sections helps tell the story of the song, providing moments of rest and contrast between the high-energy sections. The cycle of sections ends with section IV's lyrics, “Waste no more days,” emphasizing that this is the message and takeaway of the song.

Performance: I enjoy the attitude and message of this song. The groove is fun to sing on top of as well.

Thoughts from my reflective journal: “So far it seems to be more successful, with less restrictions but more specificity on the restriction I have found myself having more ideas and things to work off of.”

Results:

Overall, this retrial of the method was more successful to follow and produce music from. To me, it had a good balance of giving an objective without controlling too many aspects of the music. I enjoyed the element of self-awareness and personal reflection involved which, as mentioned in the drawbacks of the first attempt, may make this method difficult for beginners to use. However, for a composer who already has a practice, this might provide an interesting new way of thinking about style, habits, and what has already been written. I also find it to be a refreshing contrast to many exercises I encountered in my research that encourage creativity by adding a new element. While this does provide a new challenge, it does so with one’s previously existing tendencies.