The evolution of voice health

Physiological, psychological, and environmental elements that support and improve voice function are now included in the concept of voice health. Warming up and cooling down before and after singing, avoiding forcing, speaking with voice coaches, understanding one’s vocal limits, resting the voice, staying properly hydrated, and other techniques are among the skills that are usually taught in formal music education and end up in the toolkits of professional singers in almost every genre [1]. But the majority of this information comes from relatively recent scientific and technological advancements, especially in the fields of medicine and anatomy.

Prior to the 1800s, there was no official education or expertise on voice health and care. Artists who wanted to take better care of their voices turned to a range of books, guides, and tools. This information functioned within a wider framework of narratives relevant to public health during the 19th century and was based either on superstition, medical advice, or a combination of both. Vocalists had access to a wide variety of general literature on vocal hygiene, which served as background information for their medical environments. They also had access to detailed instructions from well-known literature from the era, which many singers had probably used as a reference while creating their own health regimens. But the books and guidance provided to singers lacked scientific rigor and were frequently based on anecdotal information. Prior to the 19th century, most of knowledge about voice health was derived from personal experiences and beliefs rather than from scientific research and medical knowledge.

In the 19th century, the line between scientifically sound medical advice and quackery was often blurred. Singers, in their quest to maintain vocal health, encountered a variety of treatments that ranged from the legitimate to the dubious. Quackery, as defined by legal historian Leonard Le Marchant Minty, referred to individuals without medical skill who claimed expertise and profited from self-praise and disparaging competitors. These quacks often exploited the poor and the desperate, using old wives’ remedies and herbal concoctions passed down through generations.

Singers might have turned to such quacks for fear of losing their voices, which could spell the end of their careers. The fear and the desire for magical intervention to prevent such a calamity were key elements that drew people to superstition. Singers could have consulted a mix of formal medicine and quackery, what is described as a synthetic approach to health. This could have included herbal remedies, homeopathic treatments, and other non-traditional therapies that were prevalent at the time.

Despite the potential risks, singers were often educated and financially secure enough to investigate and pay for healthcare and products that promised to maintain or improve their voices. However, the historical record lacks detailed information on the specific practices of quackery or alternative medicine that singers might have used, leaving a gap in our understanding of their health regimens.

Also during the 19th century, women played a significant role in vocal health care, though their agency was often constrained by patriarchal medical and social structures. Despite these limitations, women managed to exert some control over their health regimens. Opera singers, for example, were able to afford health consultations, self-education, and various equipment to maintain their vocal health. This autonomy was significant, given the era’s widespread condescension and misogyny in health narratives, which often focused on menstruation and hysteria.

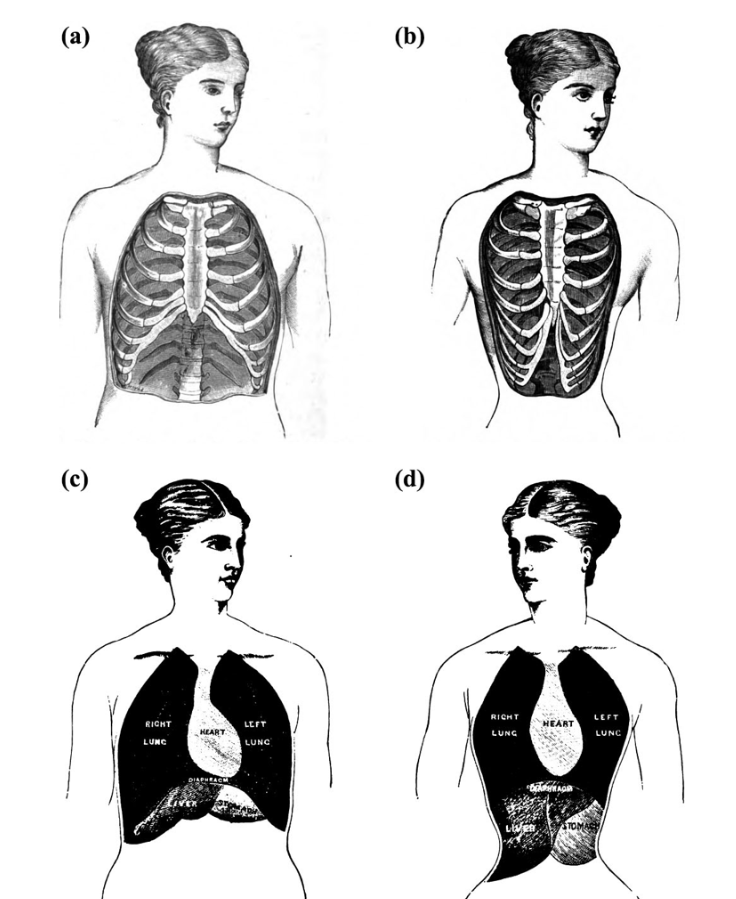

Women opera singers’ health practices were informed by an increasing body of medical literature on vocal hygiene. This literature provided detailed advice on maintaining vocal health through balanced diets, exercise, and proper clothing. Notably, female singers had to navigate societal expectations and medical advice that often conflicted with their professional needs. For instance, they were advised to avoid tight corsets, which could impair breathing and vocal performance, and to wear flannel drawers during menstruation to avoid painful menstruation and voice suppression.

These health regimens, while sometimes guided by male experts, showcased the singers’ ability to adapt and take charge of their own well-being. This autonomy, however limited, helped them maintain their careers and challenged some of the patriarchal stereotypes of women’s health during the period.

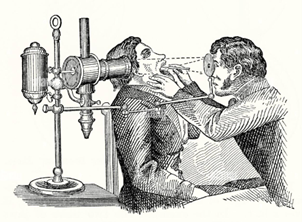

By the middle of the 20th century, research on the human voice’s acoustics, physiologic tests, neurologic examinations, and anatomy had become increasingly multidisciplinary. The field of laryngology underwent formalization and its principles on voice health were altered [2]. Doctors such as Paul Moore and Chevalier Jackson were among the first to diagnose and treat vocal abnormalities using laryngeal surgery and voice treatment [3], and Sir Victor Negus, a well known United kingdom scientist, took it further to the comparative anatomy and physiology of the larynx [4]. The development of the laryngoscope and other medical equipment transformed how vocal fold function was visualized and evaluated, allowing for more accurate diagnosis and treatment planning [3:1].

In a same way, as science and technology advanced, so did teaching and voice health education. Early in the nineteenth century, there was little interest in the art and science of voice care, and the majority of patients with diseases of the vocal system were trained and rehabilitated by professionals who specialized in public speaking, interpretation, and elocution, using conventional techniques. But following the war, there was a change toward a more multidisciplinary approach that emphasized the value of voice care and voice science, especially in the United States of America. An important turning point in the global awareness of voice research and care was the inaugural International Voice Conference, which took place in 1957. As a result of this multidisciplinary conference, which emphasized the value of human voice in the era of mass media, the Gould Foundation was founded to fund voice research [3:2]. All things considered, the history of voice health education has witnessed a shift from conventional techniques to a more thorough and scientific approach, emphasizing multidisciplinary research and cooperation.

References

-

dukevoicecare.org ↩︎

-

Paul Watt, 2024, How Did Nineteenth-Century Singers Care for Their Voice?, Royal Musical Association Research Chronicle ↩︎

-

Hans von Leden, 1990, Pioners in the Evolution of Voice Care and Voice Science in the United States of America, Journal of Voice Vol. 4 No. 2. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Victor_Negus ↩︎