III. (R)Evolution: a brief history of the bow and right hand technique

The bow has always been an inherent element of playing the violin. Although instruments played with bows had existed since around six centuries before the birth of the violin, the violin bow was born together with the violin in the beginning of the 16th century1. Since that moment until our days, the bow, as well as the violin, has undergone several changes that make the modern bow we use today very different from the one used during the 16th and 17th centuries. These changes, that will be explored in this chapter, have come along with the evolution of the music: the new musical ideas needed a different tool to be better expressed and the improvements made by the luthiers allowed the composers and the violinists to use the violin and the bow in a different way.

To have a proper overview of the evolution of the bow it is important to underline the fact that before the introduction and acceptation of the Tourte’s design around 1785, a standard model of bow had never existed2. Thus during the baroque period and especially during the 18th, century a lot of bows that differed from each other in terms of length, shape, weight or balance were in use in different places at the same time3. Nevertheless, we can see that this evolution, documented by iconography (paintings of that era like those next to this lines), testimonies, and extant bows of the time, points in a direction, the Tourte model, and goes step by step towards the design that has been in use since the end of the 18th until our days.

17th century

The short bow

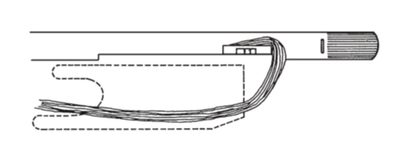

The aforementioned development starts around 1625 due to the necessity of string players, that had considerably improved their technique, of playing with more sophisticated bows to get “a clearer articulation, increased volume and a more complex sound”4. The bows from that period, called short bows by Robert Seletsky, were made of snakewood and used to weigh from 36 to 44 grams. Their length, around 61 cm, was similar to the length of the violin. The equal proportion between instrument and bow was common also for the rest of the string instruments: the cello bow was longer than it is now, being closer to the size of the instrument. The bow stick was slightly convex at the point, so there was enough space between the hair and the stick. In the first half of the 17th century, the way of connecting the hair with the bow stick changed considerably. The hair was no longer knotted at the tip (as the image c shows) and wrapped by another piece, but was introduced inside the head through a mortise and then knotted and curled inside. Something similar functioned at the frog: the hair was introduced into the stick and a removable frog was kept there by the tension of the hair. This constitutes the so-called clip-in system5(image d). This short bow, as we will discuss later, is often linked with the French dance style.

18th century

It was during the 18th century that the bigger changes on the violin and the bow were introduced. There was a frenetic activity of violin and bow makers, especially in Italy in the beginning of the century and in France in the end. The short bow was modified in such a way that by 1800 it was a considerably different object with many different possibilities. Those changes reflected the demands of the new aesthetic of the time, which the new bow fulfilled.

The long bow

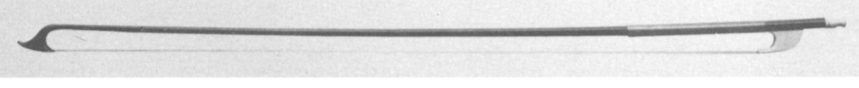

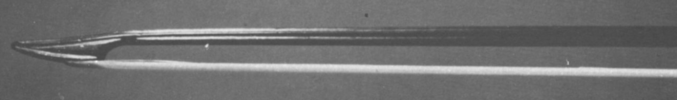

During the first half of the 18th century, there was a tendency to increase the length of the bow to 66-72 cm, augmenting at the same time the weight (45-55 grams). The previous pike’s (picture a) head was replaced by a more elevated head with a swan bill profile (picture b). The hair ribbon measured around 8 mm. This longer bow was more suitable for some musical and technical demands of the new century, such as the Italian cantabile style or the triple-stopping in some Leclair sonatas6.

A disagreement between different authors exists when it comes to designate the different types of bows during the baroque period. We have talked about the short and long bow, distinction made according to Seletsky and to the terminology of the time. David D. Boyden, however, makes another classification, which was generally assumed as true and is followed by other authors such as Robin Stowell. He maintains that before 1725 there were two bows in use: (i) the French dance bow, very appropriate for the french style because of its ability to “produce short incisive bow strokes” and emphasizing “the rhythms of dance music”7 and (ii) the bow for the Italian sonata, named by him the Corelli-Tartini bow. This term had been coined by Michel Woldemar8, a French violinist born in 1750, in his Grand Méthode de Violon (1800). Boyden recognizes the inaccuracy of this name, that puts together two violinists with very different styles and ways of playing and born 40 years apart, but he uses it anyway to describe the Italian sonata bow in contrast with the French dance bow. He prefers this term instead of baroque bow, even more imprecise9. Seletsky points out some facts that contradict Boyden’s statement. It is true, as we have mentioned above, that the longer bow is more suitable for the cantabile ideal of the Italian style than the short bow, but we know that many Italian violinists preferred a shorter bow when the longer one was already in use. Corelli was known for its powerful tone produced by a short bow and Locatelli, a student of Corelli, who lived until 1764, also preferred this kind of bow for his virtuoso music10. Tartini, for his part, may have used a lot of bows throughout his life, since he lived during a period of constant innovation11, but two extant bows of his, preserved in Trieste, are a long bow and even an early transitional bow12 (although it seems unlikely that this last one, of a “very rough quality” could have been used by a “noted master like Tartini”13). In conclusion, it is very imprecise to put together Corelli and Tartini to describe the same bow. In addition, there are testimonies which claim that some French violinists, as for example Leclair, used to play with a longer bow than many of their Italian contemporaries14. Seletsky finally clarifies that for him the history of the bow is not very related to the national styles, but more connected with different styles of composition: for the polyphonic style of Corelli, a shorter bow is more suitable, while for a more galant style (Tartini or Leclair) a longer version of the short bow is a better tool15.

To sum up, during the first half of the 18th century, the luthiers experimented with increasing the length of the bow. This new long bow was adopted at first by some soloists and progressively by more and more violinists, though as we have seen above, there were many players that continued to prefer the short version of this baroque bow. As the hair was also longer, it became more sensitive to changes in humidity and a new system to regulate its tension appeared. It is the well-known screw adjustable frog, where the hair is introduced in the frog and not in the stick, as it used to be with the clip-in frog. The frog is attached to the stick with a movable system, using an eyelet and a screw16. We can see an example on picture g.

All these bows, despite their differences in length, have many characteristics in common that make them produce the sound in a particular way and distinguish them from the later bows (the so-called transitional bow and the Tourte model, also known as modern bow). These peculiarities are given by its slightly convex bow stick and its more yielding hair, that together make the basic stroke of this old bow a non-legato bowing, with clear articulation of every note, especially in the middle of the bow17. This short, light and unaccented stroke without leaving the string, if speeded up, is similar to the spiccato achieved by a modern bow in the middle or lower half (as we can hear in the example 1). In addition, the attack of this bow, as a result of the above-mentioned characteristics, is not immediate: in the beginning and end of every note there is a “small, if barely audible, softness”18. Due to this special quality Tartini warns us that if we try to put all the pressure at once with this bow as we do with the modern one, we will get a “harsh, scraping sound”19. We can hear in the example 2 a natural attack of this type of bow in contrast with the one achieved by a modern bow. With a baroque bow, being lighter, especially at the head, the violinist can achieve more easily the fast string crossings and the broken chords, that will come out in a clearer way20.

As we have seen, in spite of the characteristics they have in common, the great variety of bows used all over Europe during the end of the 17th century and the first half of the 18th century make the task of making a clear and irrefutable classification of them very difficult.

Transitional bow

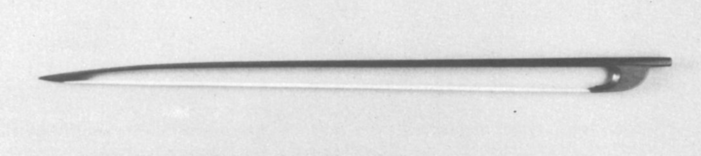

During the second half of the 18th century, around the 1770s, a sort of new bow, as varied as the previous ones, started coexisting with the already known long bow21. It is the transitional or classical bow, also called Cramer bow, after the German violinist Wilhelm Cramer (1745-1799)22. Some of the principal changes of this new bow were the slightly concave curvature (we can appreciate this change on images h and i) and a more developed head23, which was even more raised up24. The battle-axe profile (picture j), and the hatchet profile (picture k), were typical on these bows, even if the last one was eventually more successful25. Even though there were shorter transitional bows than long baroque bows, the tendency was again to increase the length as well as the width of the hair channel26. There are extant transitional bows built of snakewood, but bow makers started to use more and more ironwood and especially, pernambuco27. The last one is a less dense wood, so the stick, in spite of being longer and sometimes ticker, is lighter28.

The transitional bow is closer to the modern bow than to its predecessor; in Boyden’s words it constitutes “a decisive step towards the modern bow”29. It preserves the lightness of the old bow so the player can get a “natural softness of articulation”30, while its new curvature allows the violinist to have more precise attacks31.

The transitional bow constitutes an experimentation that led to the standardization of the Tourte model.

Tourte bow

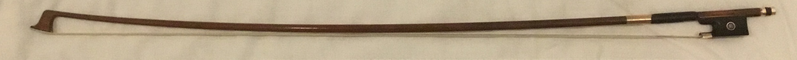

Between 1880 and 1890, François Tourte, a Parisian bow maker, introduced some new elements to the violin bow that, as we have seen, had been in constant change during the whole century. Those features included a greater length (around 74-75 cm), a more pronounced concave curve (see picture l), a heavier weight (57-60 grams), a greater strength, a better distribution of the weight along the stick, and a closed, rectangular frog with a mother-of-pearl slide covering the hair and a gold or silver ferrule to keep the broader hair ribbon (of 11 mm) flat32 (see picture m). This bow was the result of a long evolution and it became the first design that served as a model, that is to say, it turned to be the standard bow from then until today. Even though it was finally adopted by all the violin schools, the older transitional design was still made and in use well into the 19th century (see a litograph from Karl Begas from around 1820 of Paganini holding a classical bow here).

The aforementioned characteristics of the Tourte bow enable an immediate attack and a quicker response, since the hair can be with greater tension. Besides the elasticity of the bow in combination with the tautness of the hair bring naturally the so-called springing bow strokes, such as spiccato, sautillé or ricochet33. Because of its weight and good balance it gets a more powerful tone and an easier legato sound. Actually, with the heavier tip of the Tourte bow and the possibility of making a strong attack in this part of the bow, the difference between down and up bow is considerably reduced, and the bow changes if performed with a good technique, can be hardly audible. This issue of down and up bow, that concerned Leopold Mozart and many other violin players in the late 18th, mostly in Germany and France34, does not have so much importance when applied to the modern bow, since the differences are not so obvious. Nevertheless, the basic rules of beginnings on strong beats played with a down bow and the upbeats with an up bow were generally kept.

Musical reasons of the evolution into the Tourte model: Controversy over the bounced or springing bow strokes with the classical and Tourte bow

The musical reasons that led the bow makers to develop the bow in this way are under discussion. There are some elements that should be considered. The longer, more sustained phrases with long cantabile lines in the music of the end of the 18th century and later can be more easily played using a longer bow with a concave curvature, that is: a classical or a modern bow. The accented bow strokes required to play some new musical effects such as sforzando or martelé stroke are also more easily achived by a modern bow. The increase of volume in the tone that comes naturally with a heavier, better balanced bow is also quite evident35. The polemical element are the springing bow-strokes that are naturally performed with a transitional or, especially, a modern bow. Seletsky defends that the main reason of the evolution of the bow towards the transitional and subsequently the Tourte bow was the seeking of these bounced bow strokes, typical from Mozart or Haydn’s music36. Clive Brown, as well as many historically informed performers, detracts from the idea of the springing bow strokes as a common element in the performance practice of the end of the 18th century. Soloists such as Cramer used this kind of new effects but apparently there were some opponents, like Leopold Mozart or Ludwig Spohr37. The last one, who was a declared admirer of the evolution of the bow (“the bow has been so much altered for the better, that it seems no longer capable of further improvement"38), refering to Tourte's model) critize the use of springing bows by some violinists of his time in his diary by 180339. Undoubtedly, the springing bow strokes had a great development during the first decades of the 19th century, thanks to the possibilities that the Tourte model offered, but it seems unclear for me wether the use of those first bouncing bow strokes came as a consequence of the changes in the bow construction or wether the old bow was modified in order to be able to produce this kind of articulation, as Seletsky defends.

The figure of the bow maker

It is not a coincidence that the only bow maker mentioned above is François Tourte. In fact the figure of the bow maker remains anonymous until the second half of the 18th century. Before that, either the violin makers made also the bows or had someone to make the bows for them40. The first bows frequently stamped with the name of their craftsman are of a transitional type41. The different models of bow were named after important violinists that had supposedly used them. Woldemar’s list of bows (see picture n) is a clear proof of this fact. Even François Tourte hardly ever stamped his own bows. His model was named in the beginning, as we can see on Woldemar’s illustration, after Giovanni Battista Viotti, the great Italian violinist that presumably worked with Tourte on the innovations of his design42.

The evolution of the right hand technique and its relation with the evolution of the bow

If we have spoken about an unstandardized scene of the bow model before the 19th century, this can also be applied to the right hand technique. If there were a lot of different bows in use, as well as different violins, we can assume that a wide variety of styles, bow strokes and diverse vocabulary coexisted43. We could never talk about a standard way of playing when the tools the violinists had, differed so much.

There are many factors that affect the holding of the bow and the position of the right arm. We will first talk about the last one. The position of the violin has a paramount importance. If we look at the indications from influential violinists from the first half or the mid-18th century, such as Geminiani or Leopold Mozart, we will see that the elbow was kept near the body (see pictures from Leopold Mozart’s Violinschool here). The violin was held at that time with the right side of the tail piece under the chin. To avoid raising up the elbow when playing on the G string, the violin was slightly inclined towards the E string side44. There was a tendency to raise up the elbow when the position of the violin changed to the left side of the tail-piece. Nevertheless, this came quite late. Baillot, Rode and Kreutzer and Spohr, who already placed the violin with the G string side under the chin recommended not to raise up the elbow and to keep it near the body45,as the images here show. According to Joachim, this was a misunderstanding of the indications from those who held the violin in a different position, and was no longer useful with the new position of the violin46. In the modern technique the position of the elbow and its relation with the wrist vay from one school to another, but we could generally say that the elbow is no longer kept so close to the body and that this change was a consequence of the different position of the violin.

Regarding the position of the hand and the fingers, it varied according to personal taste, national style, demands of the music or type of bow used47. Indeed the characteristics of the bow used, are very important for the resultant behaviour of the right hand. With the already mentioned great variety of bows in use some violinists may have developed its technique trying to adapt to the tools they were using48.

The greatest change regarding the right hand came with the position of the thumb under the bow stick and not under the hair. The old thumb-under-hair grip became obsolete with the arrival of the ideals of the Italian sonata style and the cantabile, which were easier to perform with the thumb in the new position. In 1738, Michel Corrette writes about these different ways of holding the bow, one Italian and the other French, but defends that both are equally good49.

The position of the hand with regard to the frog has suffered a general tendency to get closer to the nut. Geminiani or Mozart recommend to place the hand at a small distance from the frog, and even later, there are evidences and testimonies that confirm that many violinists held their bows at a considerable distance from the nut50. But towards the 19th and 20th century the position of the hand in a lower point of the bow was generally assumed.

We could give some information concerning the position of the fingers. The index finger is responsible from putting pressure on the bow and taking it away to make dynamics, sometimes by its own (according to Geminiani51) or with the help of the rest of the fingers and the hand (as Tartini suggests52). During the 18th century, the index finger was mostly placed at some distance from the rest of the fingers to easily put the aforementioned pressure, but with the Tourte bow there is not so much need to put pressure on the tip, because of its more equal distribution of the weight along the stick, so the fingers tend to come closer to each other53. That may be an example of how the evolution of the bow affected the position of the hand in a direct way. We find proofs of that in Baillot’s recommendation of keeping the index finger close54 or in Spohr’s Violinschool (see pictures here). Another issue with the first finger is the point of contact with the stick, which results as varied as the other questions we have seen. Leopold Mozart defends placing the bow under the second joint55,while the later German school after Tourte, tended to place it under the first joint56. In France, Baillot recommends the point of contact on the second joint57 and this is maintained throughout the Franco-Belgian school together with a slight pronation of the lower arm and hand58. With Leopold Auer (1845-1930) and the Russian school, the bow was placed under the line between the second and the third joint, while the first and second joints were embracing the stick to achieve “the greatest tonal results... with a minimum development of strength”59.

Regarding the position of the thumb, the situation is again similar. We cannot trace a clear line or an evolution. It was Baillot who first wrote the idea of putting pressure also with the thumb, in other words, counterbalancing from below the pressure coming from above to avoid scratching the sound60. The importance of this function of the thumb is of extreme value for the sound. Bending or not this finger is also a question that appears when reading the old masters of the violin. In general in the old and modern technique, above all when playing on the lower half, the thumb is bent as we can see in the pictures here, but Baillot strongly recommends not to bend it61. The position of the thumb with respect to the other fingers also varies between the different authors, but the general rule seems to be placing it in front of the middle finger.

We could go into detail with the rest of the fingers, the wrist, the straight or inclined stick... but as we have seen, it is more a question of different schools and different ways to produce the sound than an evolution towards one clear point, like the evolution of the bow.

On the other hand, there are some aspects regarding right hand technique and way of producing the sound that remained equal throughout the history of the violin. The parallel position of the bow and the bridge, the principle of playing louder near the bridge and softer on the fingerboard, the application of pressure to get more sound, or the passive role of the upper arm are some examples.

An element that seems to appear quite late in a frequent way is the speed of the bow. It is an important part of the description of the use of the bow in the 19th century but not so common during the 18th century62. That could indicate a preference for the slower bowings in the 18th and a tendency to increase the speed of the movements in the classical and romantic music.

The evolution of the bow itself affected the right hand technique in few aspects that have already been mentioned. Nevertheless, this evolution came along with a wider variety of bow strokes that needed to be described with a higher and higher precision. Thus the right hand technique was deeply analyzed by all the great pedagogues and masters of the violin, and that is the reason why we have more concrete information about it from the 19th and 20th century than from before, when the indications were less strict.

We should also consider the changes on the violin itself and the strings as an important factor in the evolution of the right hand technique. All the developments in the bowing technique that have been made in order to increase the volume and gain projection are thought for an instrument that is not the same as it was in the 18th. For that violin with gut strings some of these features of the modern technique would definitely not work.

Summarising

To sum up since the birth of the violin bow until the appearance of the Tourte model, the design of the bow was not standardized. Even though there were many different bows in use, all evolved in the same direction: the Tourte bow. We could say that the general tendency was changing from a shorter, lighter (especially at the tip) bow with a convex curve to a longer stick with a concave shape and better balanced (heavier head). The exact moment and the order in which those changes have been made is very difficult to determine. The reasons why this evolution took place can certainly be of musical origin, but there must also be a component of experimentation on the part of bow makers. After what we have seen, we could imagine that the violinists from the 18th century were not happy and satisfied with their bows, so they wanted to make it different and better for the expression, but actually we know that for instance when the long bow already existed there were violinists that continued using the short one (a step backwards in the evolution to the Tourte design). This fact shows their non-dissatisfaction with their more primitive bow. If they found that their music could be much better expressed using a new tool, would not they use it? Were they too conservative to change, even for the better? We could think then that some new features of the new bows were introduced by bow makers without the actual need of them. Further research on the relationship between violinists and luthiers at that time could be made in order to clarify this question. In any case, due to their distinct characteristics (shape, length, balance...) the different kinds of bows naturally produce a very different sound and articulation, according to the aesthetics of the music for which they were used. Therefore, the behavior of every type of bow and the articulations they get should be considered as a reflection of the musical language of the time they belong. For this reason, playing Schumann violin concerto with a concave old bow would never come to mind to any violinist. We could do it, but it definitely would not help to express Schumann's music. In the same way the baroque bow would not be the proper tool for playing Schumann, I think the modern bow is not the best option for playing Bach or Telemann. We will delve into this question in the next chapter.

Regarding the relation between the evolution of the bow and that of the bowing technique, I would not attribute the changes on the latter only to the actual physical characteristics of every type of bow but also to the different way of holding the violin, to the ideal of sound every violinist or school pursues, to the musical demands of the current aesthetic of every period, to the different strings used, and lastly, to the personal comfort of every player. With a baroque violin held in the old way, gut strings and a baroque bow, the behavior of the right hand is of course different from playing on a modern violin with steel strings and a modern bow, but this difference does not come only from the construction of the bow.

To conclude, all the above analyses are vital and essential, but leave me also with the thought that for a better and complete understanding it is better to treat the bow, violin, right hand and left hand technique evolution as a whole within the evolution of the music.

Example 2: the first audio shows the inmediate attack of the modern bow, and the second one, the attack of the baroque bow, not so direct.

Example 1: on the first audio we can hear a baroque bow playing on the string and in the second one, a modern bow playing off the string.