Bärenreiter

Bärenreiter was established in 1923 in Augsburg, Germany. They started with publishing early music. From the beginning of this publishing house, historians were involved and research was done before publishing a new edition. Bärenreiter was the first publisher that made the complete editions. These editions were entirely made around the historic background and the research of a music piece. Bärenreiter's repertoire has been expanding to classical composers and later on to more romantic composers including Schubert and Berlioz. Lately, composers like Fauré and Rossini joined their bibliography. Besides, Bärenreiter works with a few contemporary composers. Bärenreiter is mostly well-known for their Urtext edition where they put a lot of effort in clarifying its editorial choices. A lot of their music comes with separate parts to make it easier to understand for the musician what they edited and what is the raw version.

Boosey & Hawkes

Boosey & Hawkes was founded in London in 1930. The main focus of this publisher was to publish music of contemporaries. Early investment in young promising composers lead into a big collection copyrights on the music of composers like Stravinsky, Bartok and Prokofieff. Living composers include Steve Reich and John Adams. Jazz composers are attracted to have their music published by Boosey & Hawkes as well. Next to publishing scores, Boosey & Hawkes also started from the beginning to catalogue music recordings, having a variety of original recordings usable for all kinds of media.

Breitkopf & Härtel

With their founding year in 1719 (Leipzig, Germany), Breitkopf is the oldest music publishing house in the world. The firm started with scientific and theological books. Soon the first sheet music was printed. Ever since Breitkopf published music scores of German speaking composers including Bach, Mozart, Beethoven and Schubert. In the 19th century the company made also pianos and was the publisher of the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung, one of the first major music journals.

Similar to Boosey, Breitkopf works togehter with contemporary composers, all of whom are German or at least German based. Besides, Breitkopf publishes a lot of pedagogical editions (instrumental methods) for beginners. Recently this publisher also started an Urtext-line. More and more of their bibliography is changing into an Urtext edition.

Donemus

Donemus is a Dutch publisher that manages all contemporary Dutch music. Founded in 1947 it published more than 1000 works. The company sells sheet music of over 600 composers who are Dutch or have a working relationship with the Netherlands. The bibliography goes back to the beginning of the 20th century. For almost all of the scores that are sold by Donemus, the copyrights are owned by this publisher. A great majority of Dutch music has been published by Donemus.

Durand

Durand has been established as one of the most important publishers of French music over the last 150 years. Composers such as Saint/Saëns, Debussy, Ravel, Poulenc, Messiaen, and Milhaud had their music published with Durand. Ever since, this pbulishing house has been representing new French music. The collaboration with another French publisher Salabert (light music) and Eschig (brought foreign publishers to France) has lead to a publishing house that is recognised all over the world.

Editio Musica Budapest

By the name ‘Hungarian State Music Publisher’ the company was founded in 1950 as result of the communistic influence of the Sovjet Union. Before, many smaller publisher were active in Hungary. The most well-know was Rózsavölgyi & Co.. Composers such as Bartók, Kodály and Dohnányi had their music published by this firm. From 1950 onwards, the company has been focussing on Hungarian music exclusively: classic, folk, church music and music for educational purposes. When at the end of the 60th’s all firms had to become financially independent, new ways had to be found: export became really important. To have a good profile towards foreign customers they changed the name into Editio Musica Budapest. In the 90th’s the company started to collaborate with other publishers so they could sell their music to others and for the domestic market they could make new editions based on editions from other publishers. Editio Musica Budapest is still a big house for domestic contemporary composers because of their international network.

Edition Peters

At the end of the year 1800 the composer Franz Anton Hoffmeister established together with organist Ambrosius Kühnel the Bureau de Musique. Based in Leipzig they published books and sheet music. Besides, they sold instruments as well. The first publications included the Haydn quartets and Mozart’s quartets and quintets. Soon a few works by Bach and Beethoven (including his first symphony) were published. Also more theoretical publications were made such as the violin methods of Rode and Kreutzer. In 1867, the name ‘Edition Peters’ came into existence. By this name Bach’s Wohltemperierte Klavier was the first publication. The bibliography mostly contained German Austrian composers. Because of the Nazi regime in the 1930s the son of the Hinrichsen family (by that time the owner of the company) fled to London, where he established the Hinrichsen Editions, which later on also became Edition Peters. Another son, Walter, emigrated to the United States and established C. F. Peters Corp., New York. Therefore the network of Edition Peters grew intensively. Many orchestras played from their editions and also in the chamber music world, the company was represented really well. With the growing interest in the Urtexts they lost ground in the chamber music and violin repertoire. That is the reason that starting last year, the company comes with Peters Urtext, starting with all Haydn quartets again.

Henle

Henle was founded in 1948 by Günter Henle (a politician and industrial magnate). Playing the piano he realized that a lot of sheet music was edited in such a way that the intentions of the composers had been partly lost. His idea was to create new music editions that would come as close as possible to the original ideas of the composer. It is acclaimed that Günter Henle invented the word Urtext although he never protected it with copyright. Besides the importance to have ‘clean’ sheet music, the level of usability and durability were major cornerstones for Henle. The bibliography of the company entails composers from early baroque up to the first half of the 20th century.

International Music Company

International Music Company was established in 1941 by A. W. Haendler. Based ins in New York, the company soon became one of the most prominent publishers in the United States. IMC is now a part of Bourne Company Music Publishers. Sheet music of IMC is never Urtext, but always edited by musicians. Regarding the violin repertoire, these musicians include amongst others: Josef Joachim, Carl Flesch, Ivan Galamian, Josef Gingold, Eugène Ysaÿe, David Oistrakh and Aaron Rosand. These editions can be of interest when you are looking for specific fingerings, bowing and articulation remarks. Especially the etudes are popular for this reason.

Universal Edition

This publishing house was founded in Vienna in 1901 with the idea to become more independent of the import of sheet music from mainly Leipzig (Peters) and to make recently composed music more accessible . It started with the obvious classical and romantic composers but next to this also educational literature was part of the bibliography. In that time a lot of new music was written and many of the composers had a contract with UE and came under their the umbrella. For example: Gustav Mahler, Arnold Schönberg, Alban Berg, Anton Weber, Alexander Zemlinsky, Leos janácek, Dmitri Shostakovich, Béla Bartók and Darius Milhaud, all had their works published by UE. To maintain their profile as contemporary music publisher they started to publish works from amongst others Karlheinz Stockhausen, Arvo Pärt, Pierre Boulez and György kurtág. In Austria, UE represents other publishers such as Durand, Schott Music, and Editio Musica Budapest.

Schott Music

It was clarinettist Bernhard Schott who established Schott Music in Mainz in 1770. In the beginning mainly publishing music of the Mannheim School, Schott provided a lot of musical equipment for the city which had a really cultural society. From the start, this publishing house has a lot of music from contemporaries. During the French occupation of Mainz from 1792 – 1814 they got close connections with French composers. Also important works by Beethoven (9th symphony) were published by Schott. The success of Schott Music made opening of new dependances possible. This brought the publishing house to Antwerp, London, Leipzig and Brussels. Because of the international connections, the company had also many international highly-regarded composers under their contract (Gounod, Rossini, Donizetti). A few decades later Wagner was the most important composer represented by Schott Music. More than 800 editions of Wagner appeared under the name of Schott. In the 20th century it was Igor Stravinsky who had an exclusive contract with Schott. Since 1970, Schott started with historical-academic complete editions of works that had been published by them before: Wagner (completed in 2013), Schumann, Schoenberg and Hindemith are a few to mention. Nowadays Schott works together with composers such as: Toshio Hosokawa, Fazil Say and Jörg Widmann.

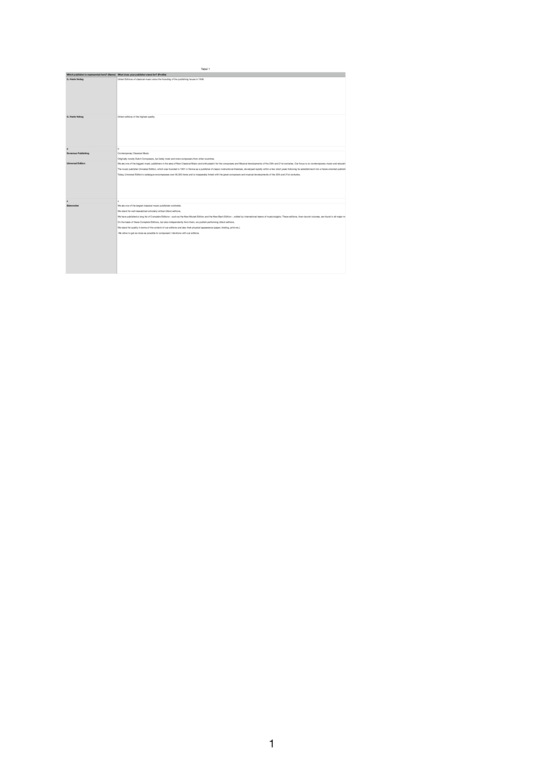

How do publishers present themselves?

For all classical music that has been written over the centuries the following can be mentoined: there have been a lot of changes in the way of playing and in the way of music has been published since the start of classical music's history and the present time. Some publishing house exist already for more than a century, other are relatively young. This chapter will visualize the differences between a few of the most popular publishing houses and create a profile of these publishers. The following publishers will be discussed: Bärenreiter, Boosey & Hawkes, Breitkopf & Härtel, Donemus, Durand, Editio Musica Budapest, Edition Peters, Henle, International Music Company, Universal Edition and Schott Music.

The above-mentioned overview of the publishers is based on the information they give at their official website. There are big differences in the way publishers present themselves. Some give a lot of information about their history and the kind of editions that are published. Others are less informative, the most striking example here being the website of IMC: no information is to be found about the company and the website contains just their bibliography and a web shop. All publishers give the possibility to reach them by e-mail. To make a better profile of the publisher than using only their website, a questionnaire was sent to the publishers concerning their profile and their ideas, as a part of the present research. Unfortunately the response was less than hoped or expected. After repeatedly sending e-mails or sending messages on their official Facebook page just four companies filled out the questionnaire. These four were Henle (twice), Bärenreiter, Donemus and Universal Edition.

The first question ‘What does your publisher stand for?’ has been answered with the same answer that could be found on the website. The next question ‘In what way is your publisher different from other publishers?’ has been answered in different ways. Where Henle replies that they do only copyright-free music according to the Urtext method, Bärenreiter aswers more extensively: they mention that the practical aspects of their editions are very important and distinctive as well. Universal Edition stresses its focus on contemporary music (‘performance material’) and pedagogical methods. Donemus distinguishes itself by having all their scores available as hardcopy and PDF and emphasizes its role as network for the Dutch contemporary music society.

The next question is ‘In what way does a publisher influence the interpretation of a musician?’. Donemus does not see any role in it because according to them the responsibility of the content lies in the hands of the composer. The way scores are edited or designed is for them less important. UE gives as reaction that they influence by putting bowings, fingerings and articulation remarks that fits in the picture of a performance edition. Henle claims it could be influenced by the practical use of the score and that the content should be clean. Bärenreiter explains a bit differently that to reach an accurate way of reading they always explain in background information what certain symbols means and how it could have been played in the period of the concerning composer.

The question ‘What makes an edition popular to violinists (based on your experiences)?’ gives actually three answers: reputation of the publishers, user-friendliness and also accuracy. Striking is that Donemus answers the question with ‘an edition should be perfect, respecting notational conventions, with strong skills of graphical design etc.’ although in the question before they put the responsibility of the content in hands of the composer.

The following question contains a few words that should be ordered from ‘most important’ to ‘least important’. The words were: Urtext, price, instructions of playing by a musician, background information, readability of music and quality of paper and binding. These words concern the question ‘What is the most important for your publisher to customers?’. Both Henle and Bärenreiter have ‘Urtext’ as first priority and ‘readability’ or ‘quality’ are second or third and price is their least concern. For UE ‘Urtext’ is the least concern, where ‘readability’ and ‘instructions of playing’ are very important to them. For Donemus, ‘accessibility’ and ‘price’ are the most important and ‘binding’ comes last.

‘What is the average lifetime of an edition?’ has been answered in different ways: the companies themselves keep selling the same edition between five years and a few decades. Donemus is the only one that answers with ‘endless’. Henle gives also a reply concerning the physical bookwork in use of a musician: paperbound should last up to 20 years where clothbound editions should last up to 50 years.

The next question concerns reasons why an edition should be revised. For Henle and Bärenreiter it is when new resources has been found. For Donemus it is the composer who decides. UE replies with ‘whenever it is not state-of-the-art anymore’. Probably this concerns playing techniques which develop over the years or when there is evidence that the composer wants something else.

The following questions are about the size of the company. The first is ‘How many people are working at your publisher?’ As mentioned before, Henle filled out the questionnaire twice and somehow the reply on this question differs a bit: one person answered with 26 people, the other with 28. Donemus is the smallest of the four publishers with eight people. UE has 60 people employed and Bärenreiter is by far the biggest company, with 120 people people working for them

At Henle 5 of them are editors (both people answered the same number), Donemus has between 3 and 5 but just as copyists, UE has 6 editors and Bärenreiter 17.

The background of the editors also differs per company: at Donemus it are musicians and composers. UE has musicians and historians as editors. At Henle everybody has a PhD in musicology and plays music (not necessarily professionally) and at Bärenreiter some are musicologists and others are professional musicians.

Concerning the market of the publishers, both UE and Bärenreiter sell mostly in Germany or German speaking countries and most scarcely in South-America. With Henle the answers depends: one person claims that the biggest market is the United States, the other person puts Europe first and the United States second place. Asia is also mentioned as an important market. Donemus sells mostly in the Netherlands but also in other European countries. Africa appears not to be important as market for sheet music

The last two questions are about the future. Everybody mentions the change from paper scores to digital sheet music. UE thinks they will stay important because of the copyrights they have on a lot of their bibliography. Henle and Bärenreiter claim that their quality will always be an important aspect in musical life. Donemus just mentions the transition of their bibliography to PDF. All four of the companies are already digitalizing their products although Henle and Bärenreiter seem to be one step ahead: they both already have an app where you can buy the music, read from it and make notes in it.

With this questionnaire a better look into the functioning of publishing houses was shown. The four publishing houses represented in the questionnaire all adapt with the digitalization of the world. Striking are the reasons that are mentioned for how they will survive: the two Urtext publishers are convinced that the quality they deliver will be the reason. The other two publishers have reasons such as the copyrights they own on certain music or their function as dealers (web shop) because they sell less in an actual music store.