(Full Text Below)

Abstract

This artistic research project investigates the ceramics workshop as a dynamic site at the convergence of art, pedagogy, and ecopolitics. Utilizing practice-based, iterative feedback loops, it explores how cycles of making, reflecting, and teaching with clay evolve concepts, methods, and material outcomes in an ongoing dialogue between agencies.^1 Clay is reimagined beyond a primitive arts and crafts medium as an infrastructural archive that embodies ecological, political, and urban narratives.

Grounded in a material-ecological framework and informed by critical theory from Bruno Latour, Karen Barad, and Donna Haraway, the project situates ceramics pedagogy within an experimental ecology of keythings; clay, tools, kilns, residues, and bodies, that co-constitute knowledge.^2 This research embraces contradictions and complexities of wicked ecological problems, fostering a pedagogy of “comfortable discomfort” that resists mastery and embraces provisionality.^3

The research unfolds over a time of wicked problems: war, speculated ecological collapse, institutional fragility, and the difficulty of knowing which crisis demands priority or whether these crises are in fact complicit in one another. Within this uncertainty, it is also considered how to navigate complexity with mindful presence, cultivating forms of practice that allow us to remain responsive without paralysis and eventually if this approach could be conducive to locate stable solutions and re-inject questions stemming from the practice back into practice and beyond.^4

Outcomes include pedagogical models and artistic works that demonstrate how material practices mediate relations between sustainability, ethical responsibility, and creative agency. Ultimately, the project envisions the ceramics studio as a vibrant, relational ecology that invites ongoing inquiry into the entangled systems constituting artistic research, practice and pedagogy.^5

Introduction

The reintroduction of ceramics teaching to the Sculpture Studios at the Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna in 2023, supported by head of Molding and Casting Workshop, Kristin Weissenberger’s reopening of the plaster workshop for clay work and the acquisition of a new electric kiln^6, established both the necessary physical infrastructure and a meaningful symbolic foundation for workshop-led ceramics research, teaching, and practice.

Research Questions

How can a ceramics workshop function at the intersection of art, pedagogy, and ecopolitics, specifically by employing practice-based artistic research to create iterative feedback loops, where each cycle of making and learning meaningfully informs and transforms future concepts, processes, and outcomes?

In what ways can clay; a material simultaneously rooted in primitive tradition and suffused with contemporary concerns of excavation, waste, and toxicity, be reimagined as an infrastructural archive, documenting and responding to the ecological and political systems from which it is sourced?

Keythings

This project evolves from a deliberate effort to move research beyond the confines of language and abstract keywords, such as art practice, sustainability, waste, ecology, and pedagogy, toward material engagement with what it proposes as “keythings.” These keythings include clay, tools, storage materials, kilns, workshops, institutions, data, food, fire, bodies, residue, waste, byproduct, sustainability, climate, collapsology, and artistic practice. They are not inert objects but dynamic participants that co-constitute and quietly destabilize research, embodying complex material, ecological, and social entanglements.

Drawing inspiration from experimental approaches in critical and ecological engineering, such as those practiced by Tega Brain; the methodology positions keythings within what Bruno Latour describes as a ‘parliament of things.’^7^8 Here, human and nonhuman actors interact as equal collaborators in knowledge production. Situating ceramics and clay within this ecology reframes pedagogy as a collectively negotiated inquiry and practice as a material ecology, unfolding through a choreography of contradictions and ongoing negotiation rather than fixed outcomes.

Theoretical Framework

This project is situated within the field of artistic research, understood as a distinct and generative form of knowledge-making grounded in experience and practice. Following Patricia Leavy, artistic research resists reducing art to illustration or case study, instead positioning creative processes as rigorous inquiry capable of articulating complexities of lived experience, sociopolitical realities, and material entanglements that conventional scientific or humanities methods often cannot address.^9

In tandem with material philosophy and ecological thought, clay emerges as an active participant in knowledge production rather than an inert medium. Building upon Bruno Latour’s “parliament of things,” the studio assembles clay, kilns, tools, food, bodies, and fire as collaborators in inquiry.^10 Karen Barad’s notion of intraaction reinforces that meaning and matter co-emerge through entangled processes.^11 Pedagogy is reframed as artistic research in the form of collective, embodied learning; attentive to material resistances and affordances.

Crucially, this project integrates pedagogical feedback models where teachers and students engage in iterative learning loops. This dialogic process, supported by extensive educational research, foregrounds reciprocal feedback as essential for deepening understanding and fostering agency.^12 Feedback is conceived not as top-down judgment but as an ongoing exchange in which students actively interpret, respond to, and generate feedback themselves. In this co-creative feedback loop, knowledge evolves dynamically through negotiation, reflection, and shared experimentation.

Ecological theorists Donna Haraway and Timothy Morton deepen the framework by challenging solutionist impulses and insisting on embracing contradictions and complexities intrinsic to ecological entanglement.^13 ^14 Haraway’s injunction to “stay with the trouble” and Morton’s concept of "dark ecology" support this artistic research stance, where contradictions serve as conditions of possibility rather than obstacles.

Anna Tsing’s conception of friction further illustrates how knowledge arises through uneven encounters, between surplus subway clay and commercial clay, institutional frameworks and student collectives, edible and sculptural forms, revealing artistic research as a site of unstable, affectively rich transformation.^15 As Patricia Leavy notes, this knowledge is experiential, emotional, and material.^16

By positioning clay as a “keything” in an ecology of practice, this project creates iterative feedback loops of making, teaching, and learning; anchored both materially and pedagogically. These loops resist hierarchies of knowing and foreground relationality, enabling artistic research to generate new epistemic spaces where knowledge lives simultaneously in material form, thought, and collective experience.

Methodology

This research embraces a qualitative, practice-based approach rooted in the iterative dynamics of artistic making, pedagogical engagement, and critical reflection emerging within the ceramics studio.^17 Data collection unfolded through attentive note-taking during studio discussions and participant observation, embedding student feedback and experiential insights as integral threads within a broader entanglement of research literature, personal artistic practice, and pedagogical encounters.

Collaboration transpired primarily horizontally among students, who responded to evolving course prompts by conceiving and realizing collective sculptural works reflecting their distinct yet interconnected inquiries. These collaborative processes served both as artistic outputs and epistemic sites, where making, dialogue, and critique continuously looped back to inform successive stages of exploration. This cyclical feedback and not a linear transmission, constitutes the core methodological framework, aligning with artistic research as a mode of knowledge production inseparable from embodied, material practice.

Central to this approach is the acknowledgment of the studio as a shared ecology, where what this project alludes to as ‘Keythings’ instead of Keywords; human and nonhuman actors including clay, tools, kilns, residues, and bodies, co-produce meaning through what Barad refers to as intra-action.^18 This methodological positioning supports an ongoing negotiation between control and openness, mastery and uncertainty, situated within material and ethical complexities of sustainability and ecological entanglement while destabilizing traditional hierarchies between subject and object.

The project employs a material-ecological framework that draws upon interdisciplinary collaboration and ecological thinking to reveal complex entanglements between urban infrastructure, waste, extraction, and sustainability. This approach is grounded in immersive studio practices, including working directly with surplus clay excavated from Vienna’s subway construction and engaging in material preparation processes such as sifting, wedging, and blending. These embodied activities bring to light the ecological and ethical dimensions inherent in material use.

The research extended across disciplinary boundaries through collaborations that brought in perspectives on ceramic waste as a form of value in guest talk/workshop with Christina Schou Christensen^19 and on clay as a medium for data storage with Martin Kunze^20. Such transversal exchanges emphasize inquiry as a shared, collective process rather than isolated disciplinary endeavors

Sustainability practices are present throughout the methodology, including intentional material rationing, reuse strategies, and thinking about energy management during firing processes.^21 The kiln itself is considered an active agent whose operational energy consumption shapes artistic outcomes and ethical decisions alike.^22 This reflects an ethic of scarcity and responsibility, resonant with themes from collapsology and material ecology.

A central aspect of this methodological approach involves navigating the moral and ethical complexities of sustainability, not as a rigid, prescriptive burden imposed on artists or students, but as a set of guiding anchor points designed to resist reductive greenwashing or tokenistic gestures.^23 The research remains attentive to the challenges inherent in discussions of ecological responsibility, acknowledging collective complicity within broader systems of collapse.^24 Recognizing that no perfectly ethical mode of living or making exists provides the ground for cultivating a space that honors nuance and rejects moralizing. This ethical stance reinforces that responsibility is distributed socially, rather than resting solely on the shoulders of individual artists.

In sum, the methodology enacts practice-based artistic research as a dynamic feedback loop where cycles of making, reflection, and teaching continuously inform and transform one another. This iterative process opens spaces for evolving conceptual frameworks, material experimentation, and a shared ecological consciousness within the ceramics workshop.

Teaching and Workshop Practice

Ceramics 1 (2023-24)

In winter of 2023, I started teaching Ceramics 1, a foundational course designed to introduce art students to key handbuilding techniques in ceramics. The course focuses on instruction in pinch, coil, slab, and hollow forms, alongside essential finishing methods. While the primary goal is to develop strong practical skills through intensive studio practice, I also encourage students to consider wider significance of ceramics. Alongside mastering techniques, they are invited to reflect on how ceramics connects to broader artistic traditions and global ecological and cultural issues. This helps situate their learning within a larger context without detracting from the core focus on foundational skill-building.

In the same year (2023) at the academy, students of Art and Architecture, Institute for Art and Architecture, together with Prof. Michelle P. Howard, collected a large amount of soil excavated from the Vienna tube station construction site and used it to create an artistic installation. After the exhibition, a discussion between Prof. Michelle P. Howard and Prof. Julian Göethe (Departments of Art and Space I Object, Institute of Fine Arts, Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna), facilitated through Senior Lecturer / Head of Molding and Casting Techniques Workshop, Kristin Weissenberger, explored the possibility of giving this material a second artistic life. This idea extended into the ceramics course, and I was pleased to incorporate the excavated soil as both material and concept within a workshop setting.

Teaching Project Grant: Waste is Optional between Artistic Agency and Gaze (Workshop 2024)^25

Kristin Weissenberger, played a central role in shaping the workshop we delivered together. Kristin and I came together to design a workshop titled, Waste is optional: between Artistic Gaze and Agency, for ceramics 1 students, and we decided to apply for the annual teaching project grant at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna.^26 As we began structuring the schedule and setting goals, we felt a tension between wanting to focus on essential technical skills and the deeper need to create space for critical reflection and meaningful dialogue. We were uncertain about how to balance these aims without overwhelming the students or losing sight of the creative process. Through open conversations with each other, we navigated these uncertainties together, deciding to expand the scope of the workshop to include ecological and conceptual dimensions alongside technique.

We framed our proposal around sustainable art practices as a foundation and used the notion of “waste” as a provocative tool to challenge assumptions about materials. We questioned what really counts as waste, refuse, or surplus, and how these ideas might open up new paths for inquiry and expression. The grant allowed us to gather materials for processing clay and reusing discarded substances for glazing, which felt both exciting and daunting; how to work ethically with what others discard, and what limitations or surprises might arise?

Inviting guest speakers like Christina Schou Christensen and Martin Kunze added layers of complexity and inspiration, showing us how clay can be a medium of research that connects ecology, speculative futures, and sustainability. Throughout, both Kristin and I were learning alongside the students, uncertain but committed to holding space for experimentation, discomfort, and reflection. This vulnerability, acknowledging what we didn’t fully know, became part of the workshop’s fabric and ultimately enriched the work we did together.

The workshop course’s parallel naming and evolution into the Sustainable Ceramics Group reflected a potential interest in collaborative, intersectional research with a focus on sustainable approaches to ceramics. However, I am uncertain whether this naming was the right decision, as it appeared to impose a focus on sustainability that didn’t necessarily emerge naturally from the students’ interests or practices. Despite this, we have continued to use the label, and I hope that over time it becomes more than just a greenwashing term; something that genuinely informs and enriches our practice for at least some of us.

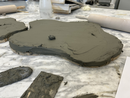

The workshop progressively evolved beyond basic instruction of techniques, as students gained experience using both store-bought commercial clay and surplus clay excavated from Vienna’s subway construction. This clay that came bagged as tons of dried raw chunks to the Sculpture Studios has its own interesting parallel story.

We incorporated primitive pottery methods to wet process, sieve, and purify this wild/city dirt into workable clay. This meticulous and time-consuming technique grounded participants in a practice of slow, generative research, emphasizing the importance of patience and care in material preparation. The final project culminated in a collaborative sculpture forming a modular Landscape that could be fragmented, recombined, and expanded. This artwork evolved through the integration of edible components, including finger food brunch and bread sculptures fired in the kiln. Such experimentation cultivated relationality, grounded the practice in research, and positioned sustainability as a tangible, everyday artistic reality.

Throughout the course, questions about the necessity and consequences of making were foregrounded. Together, we asked whether every mark, every form, every fired object was essential, opening consideration for unfired ceramics, low firing, and the potential positioning of ceramics not only as artistic objects but also as technical devices or components within a larger system of production. This led to critical reflection on the potentially extractive nature of certain artistic practices and knowledge economies, contemplating approaches that may balance creativity with ecological consciousness.

Feedback loops developed organically: insights and outcomes generated by students and collective activities continually fed back into my own artistic research, enriching both teaching and personal work while participating in a culture of reciprocity and shared learning. The dynamic movement between individual art practice and group research supported ongoing innovation and iterative knowledge formation.

Artistically, this group’s project generated works that both embodied and disrupted our collective research. The main sculpture; a shared landscape, fragmented into autonomous units and continued to evolve, initially presented with food at the Sculpture Symposium, Red threads, loose ends, another sculpture is possible,as Open Lunch with Sustainable Ceramics and later revisited alongside bread sculptures baked in the ceramics kiln re-displaying the landscape sculpture under the title, ‘Home is a place that feels like baking’ at the annual Rundgang Exhibition 2025. Each stage expanded contexts of sculpture, research, sustainability, and relationality.

Ceramics 1 (2025)

Michel Serres reminds us that knowledge is never separate from its material circumstances; it flows and circulates, deeply entangled with the things themselves.^27 In 2025, despite the absence of a teaching grant, the course continued, benefitting from the open-source knowledge developed by last year’s group; a resource now accessible to all through collective research. There is no definitive conclusion to this inquiry; each new group, and anyone engaging with it through digital platforms and creative commons licensing, can extend and enrich the research in their own way. Like a network of roots, knowledge spreads, connecting, supporting, and growing beyond any single point of origin.

A field excursion to Wienerberg Park served as both methodological case study and affective anchor.^28 This former industrial site, now reimagined as public park, provided an opportunity to foreground the place-bound politics and histories of clay. Through situated, embodied inquiry, we moved through layers of sediment, labor, and memory.

Clay, in this context, emerged as a keything; simultaneously sediment and testimony, archive and agent, object and history. The workshop’s material practices: processing, sculpting, but also listening, tasting, collaborating, mirrored and unsettled cycles of extraction, value, and neglect, prompting new questions about the social role of art and the ethics of ecological or material engagement.

The group discussion unfolded as an ecology of observation, reflection, and tactile engagement. Victor Adler’s documentation of brickworkers’ conditions; long hours, minimal wages, child labor, overcrowded barracks, and the exploitative truck system, surfaced as spectral presences in the park.^29 . Students in the workshop later, handled the clay, transforming abstract knowledge of industrial oppression into embodied engagement.

The artistic outcome from students this year 2025 is developing as a collective exhibition on ‘Voices in Clay' (working title). This project emerged intuitively as students imagined bird forms and musical instruments for the common garden at the sculpture studios building. Through reflective conversations, the group continues to explore the ways these objects contribute voices; building presence and interaction within the garden context. As we plan to continue discussions and working on this project, we will focus on how these sculptural works generate voice, may or may not mark collective memory, and animate the space as part of a dynamic material parliament.

This exhibition practice directly continues previous workshop methods, emphasizing a deliberate rationing of materials and. Working with fragments, leftovers, and rejecting extractivist assumptions of endless supply, scarcity is reframed as both method and stance. At the same time, it is clear that artists must not bear burden alone to solve or directly reckon with social or environmental issues. Artistic practice is diverse: some engage consciously with these concerns, while others embrace emotional resonance, beauty, personal reflection, or other forms of expression. The idea of voices in clay embodies this multiplicity, through many points of entry with student contributions, it speaks in many registers: sometimes loud, sometimes quiet, often in the spaces between words. The act of making itself becomes voices, as a presence that invites gentle listening and engagement with the complexity of being.

Feedback Loops and Pedagogical Reflection

Conversations in the studio inspired me to develop and share methods of rationing practice and production without judgment, and with reinforced commitment to informed, mindful decision-making.^30 Together with students, we explored the questions of whether every mark etched into clay or every sculpted object needs firing, and how unfired or low-fired ceramics might hold valuable space within artistic practice. We thought of ways to expand our understanding of ceramics beyond making pleasing objects for display or use, considering the medium’s expanded potential as industrial devices or architectural components, thus prompting critical inquiry into the material’s multiple functions, significances and future potentials.

Such investigations also led us to discuss if the difficulty lies in the use of materials in general for artists and art students. When discussing the extraction not only of physical resources but also of knowledge and disciplinary capital, we acknowledged that few practices engaged in producing material or conceptual outcomes, are exempt from extractive or transactional aspects. And this ought not to bring guilt or shame but rather a mindful approach to decision making. Throughout this process, Timothy Morton’s concept of "dark ecology" was a vital touchstone for me.^31 It guided me towards embracing the inseparability of life, matter, and destruction; attending deeply to entanglements while resisting illusions of control or mastery.^32 At times, I learned that my own artworks and those emerging from student collaborations became part of these interwoven cycles of complicity, influence and reciprocity.^33 Refusing closure, these moments of creative friction, as Anna Tsing describes, were where new knowledge/s emerged: through encounters, disruptions, and uneven entanglements rather than linear transmissions.^34

Drawing from my time in the workshop, I’m fully aware that “inspiration” often acts as a convenient label for extractive impulses, where ideas and materials just flow one way, leaving behind an uneven exchange.^35 What I’m aiming for instead is a feedback loop, a kind of creative circuitry where work sparked by the students loops back, feeding their future practices and conversations.^36 It’s not about taking, but about generating ongoing gestures of reciprocity that keep evolving within our shared ecosystem.

Using leftover clays, bits sourced from the city or grabbed from workshop remnants, I built book sculptures with fragmented alphabets. One of these pieces made it to the Academy Auction, a conscious act of giving back, made with academy materials but distinctly carrying layered meanings.

These Book-sculptures emerged from the residues of studio labor: fragments of leftover clay, slips, sieved particles, alphabet fragments. Words, letters, and text were embedded with specific codes and yet as unreadable in conventional sense, legible to touch, spatial perception, and material understanding. Here, Barad’s notion of intra-action is tangible: text and material, body and clay, knowledge and labor are entangled in inseparable relation.^37

The students’ bread sculptures that were created together with Kristin Weissenberger, as edible co participants of the collective sculpture, Landscape reorganizing once again for the annual Rundgang exhibition, Home is a place that feels like baking, in their own right, later ignited my series of Palimpsests, surfaces for baking and serving confectionaries. The bisque fired porous Palimpsests are interacted with during book readings. Reading them means tasting chemistry, witnessing accumulation, sensing fragility and contemplating collapsology. Reading them also means confronting what is left after the sweet consumption.In cookies and parathas, as with other foods where reducing sugars combine with certain amino acids, the color and the aroma is peculiarly interesting. What we crave is the Maillard Reaction.^38 These sugars meet amino acids, molecules rearrange, break, recombine. Some compounds brown food, others rise as aroma, promising comfort before the first bite. But heat also creates acrylamide, a toxic byproduct of the Maillard Reaction.^39 By bringing these works into book readings with the students, I aim to offer a space for reflection and further conversation, inviting them to engage deeply with these interwoven themes of materiality, comfort, risk, and transformation.

Through this messy, nonlinear exchange, I want to cultivate a practice where teaching, making, and reflecting saturate each other; where inspiration is less about ownership and more about circulation, connection, and nourishing the complex flows of collective creativity.

Reflecting on this ongoing research, it becomes clear that the project is less about arriving at answers and more about dwelling within complexity as an unfinished conversation where feedback loops of making, reflecting, and learning continuously intertwine with the ethical and ecological questions we face.

Sustainability in art practice challenges easy definitions or greenwashed slogans. I witnessed how students often felt unsettled by these tensions, caught between grappling with ethical responsibility and navigating an art world demanding relentless productivity and portfolio building. The creation of the Sustainable Ceramics Group was never about crafting a definitive ethical project. Rather, it served as a space where sustainability and climate discourse could be integrated into practice without sidelining the creative impulse or becoming a burden.

During the workshop, pedagogy for me was always an assertion of co-presence; a negotiation of attention, time, labor, and materiality. Collective learning emerged through material engagement, through touch, repetition, failure, and the patient observation of process. The affective atmosphere was one of comfortable discomfort, a shared space where contradictions lived side by side: clay as resource, art as practice and inquiry, teaching as instruction and mutual discovery.

Theoretical insights from Anna Tsing helped me see this pedagogy as emergent and relational, shaped by the friction between a multitude of agencies and keythings in the studio.^40 As students learned to read clay as more than material; as index, archive, and agent within systemic ecologies, they also encountered material constraints that could not be mastered simply through skill or intention, enacting Karen Barad’s idea of intra-action, where knowledge and matter co-emerge inseparably.^41

Interdisciplinary perspectives expanded this inquiry, with scientific, ecological, and technological voices provoking deeper reflection. Clay became a lens onto geopolitics, extractivism, and relationality, unveiling how everyday studio practices are embedded within expansive global networks of energy, labor, and consequence but also that ceramics is not just an art and craft material; we have ceramics components in our mobile phones and other devices, infrastructures etc.

In this light, pedagogy for me became less about transmitting skills and more about aiming to cultivate a research ecology as shared ground for experimentation, negotiation, and reflection, where students and I enter feedback loops that acknowledge complexity without demanding premature resolution. Care, attentiveness, and ethical responsiveness emerge as vital materials of practice, attuned to a world that is never neatly circumscribed but always in flux.

This reflection invites ongoing questioning and openness, recognizing that the work of sustainability in and alongside art is never complete but always a practice of becoming with.

Conclusive Thoughts

Woven throughout the project is a belief in the potential of artistic research. Leavy’s approach champions scholarship as accessible, affective, and publicly resonant, and our practices reiterated this principle.^42 In the ceramics studio, clay was both medium and interlocutor, embodying the ways in which matter, agency, and social process entwine.^43 Every outcome, whether edible, performative, archival, or ephemeral, returns to the practice as an open record: an invitation to further discourse, practice and critique.

No single object, sculpture, confectionary is an endpoint; each is a provocation to re-examine the relationships between making, knowledge, material care, and world.^44 This project situates clay as a material and conceptual hinge connecting artistic practice, pedagogy, and ecopolitics. It challenges dominant narratives of sustainability by focusing not on solutions but on material negotiation, relationality, and intraaction.^45 Clay is simultaneously primitive, speculative, infrastructural, and geopolitical. It records imagination, extraction, circulation, and labor, embodying the entanglement of artistic, ecological, economic, and political systems.^46

The research illustrates that artistic practice can act as a site for inhabiting wicked problems. War, ecological collapse, institutional constraints, and pedagogical imperatives are entangled; none can be prioritized without acknowledgment of complicity. The studio becomes a 'parliament of things', where clay, tools, kilns, bodies, food, and fire co-author knowledge.^47 These keythings provoke, resist, and destabilize, shaping research as much as it shapes them.

Rationed practice, scarcity, and working with residue foreground ethical responsibility in material use. This echoes Haraway’s call to 'stay with the trouble': learning to act responsibly within unavoidable systemic entanglements.^48 The work is a form of rehearsal for living within collapse: attentive, iterative, and materially grounded.

The artistic outcomes illustrate the inseparability of aesthetic, ethical, and epistemic inquiry in contemporary artistic research.

Future Directions

Futures direction in researching material ecologies within art practice and pedagogy could benefit from a living, breathing feedback loop where knowledge created and shared continuously feeds into new learning objectives and environments, keeping research a dynamic, evolving method rather than a fixed endpoint.^49

In this ecosystem, clay reveals itself as more than material: a political and infrastructural medium; keything, charged with histories of extraction, labor, and urban metabolism.^50 Working with clay invites direct engagement with the complex ecological, economic, and geopolitical systems shaping contemporary life.

Pedagogy practiced with an ecological gaze becomes a space of cohabitation with contradiction. In the ceramics workshop, artists, clay, kilns, food, tools, bodies, residues, co-create knowledge.^51 Instruction unfolds into negotiation; making is inseparable from reflecting on the conditions that enable it. The workshop functions as a research ecology where contradictions are rehearsed, fueling ongoing inquiry.

This awareness could extend to the delicate balance between reclaimed and commercial materials. Neither rejected nor privileged, both are situated within their broader supply chains; mined, processed, packaged, transported and revealing infrastructures invisible in the studio yet carrying profound ecological and political consequences. Working with surplus clay alongside commercial products cultivates material literacy; a recognition that every object carries a past and projects futures of waste, reuse, or disappearance.^52

Future directions invite expanding keythings mapping across materials and other agencies; exploring institutional ecologies that nurture sustainable, experimental practice; investigating edible material artistic practices; developing rationing as an artistic strategy of scarcity; and designing pedagogy that embraces uncertainty, complexity, and systemic entanglement.

Taken together, these approaches expose the inseparability of art, pedagogy, and ecopolitics through material attentiveness, co-presence, and intra-action. Clay emerges as interlocutor, collaborator, and provocateur, modeling ethical, embodied, speculative engagement in an uncertain world; a template for artistic research as a living, responsive process.^53

Bibliography

Augustine, D. A., and G.-A. Bent. "Acrylamide, a Toxic Maillard By-product and Its Inhibition by Sulfur-Containing Compounds." Frontiers in Food Science and Technology 2 (2022): Article 1072675. https://doi.org/10.3389/frfst.2022.1072675

Christina Schou Christensen. Ceramic artist. Bornholm, Denmark. Accessed June 5, 2025. https://www.christinaschouchristensen.dk/

Geschichtewiki. "Wienerberg (Erholungsgebiet)." Accessed June 5, 2025. https://www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Wienerberg_(Erholungsgebiet).

Haraway, Donna. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016.

Latour, Bruno. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Latour, Bruno. We Have Never Been Modern. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1993.

Leavy, Patricia. Method Meets Art: Arts-Based Research Practice. 3rd ed. New York: Guilford, 2024.

Leavy, Patricia, ed. Handbook of Arts-Based Research. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford, 2025.

Morton, Timothy. Dark Ecology: For a Logic of Future Coexistence. New York: Columbia University Press, 2016.

Outlander Materials. "Outlander Materials." BlueCity, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Accessed June 5, 2025. https://www.outlandermaterials.com/.

ÖGB. "Victor Adler und die Ziegelarbeiterinnen." Accessed June 5, 2025. https://www.oegb.at/themen/geschichte/victor-adler-und-die-ziegelarbeiterinnen.

Puig de la Bellacasa, Maria. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Serres, Michel. The Five Senses. London: Continuum, 1985.

Serres, Michel. Genesis. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1995.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015.

Sara Howard Studio. “Circular Ceramics Book.” 2023.

Kunze, Martin. Ceramic artist and founder of Memory of Mankind. Hallstatt, Austria. Accessed June 5, 2025. https://memory-of-mankind.com/