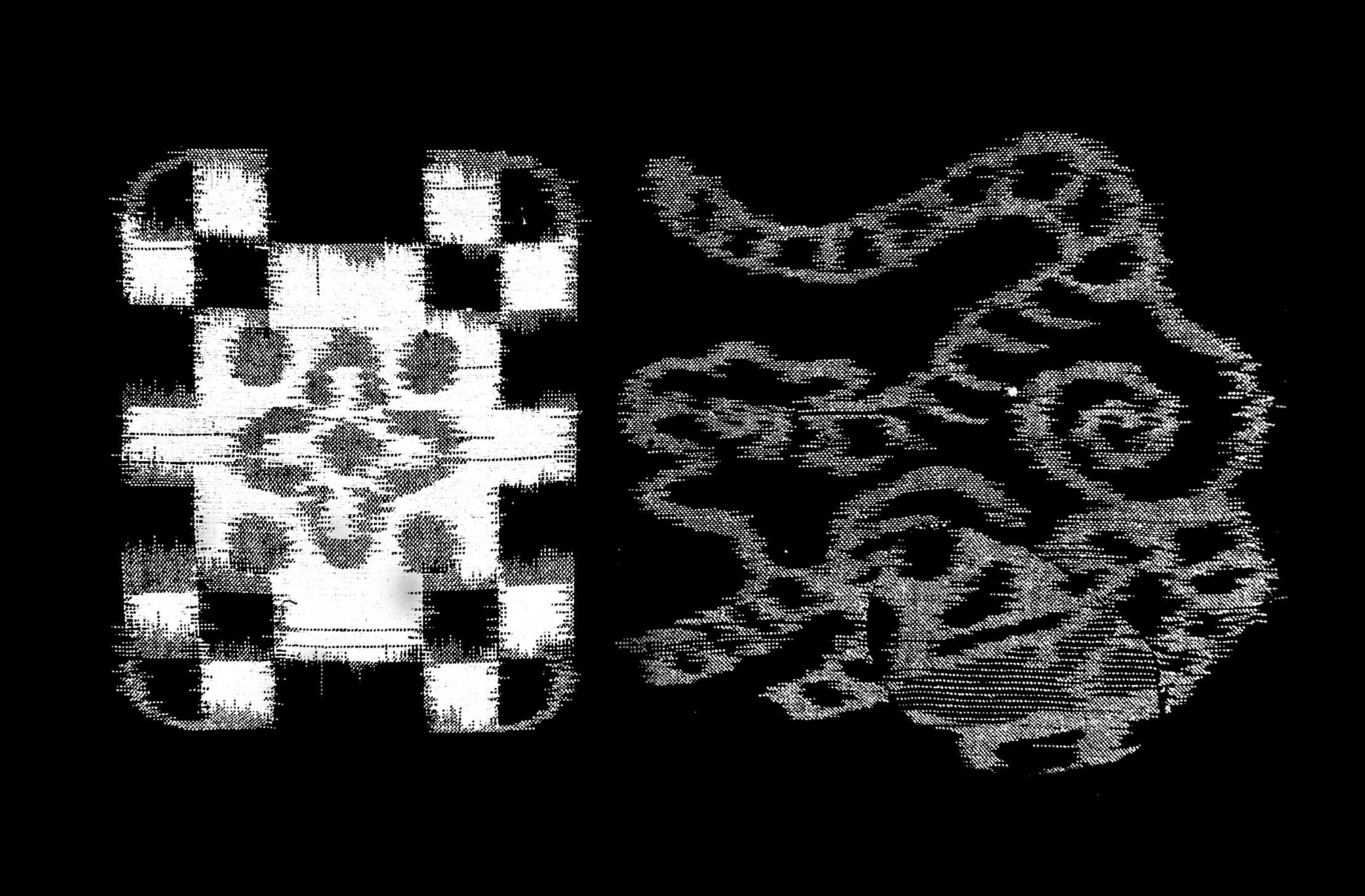

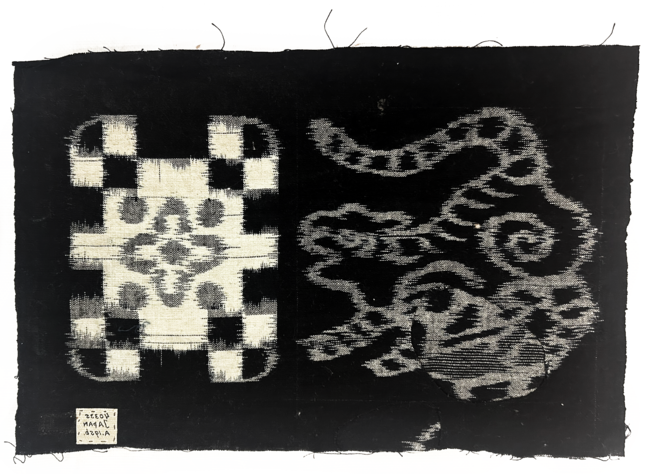

Culture: Japanese

Date: early 20th century

Size: length 22 x width 33.5 cm

Material: cotton (momen), woven indigo

(plain weave), kasuri: double kasuri

Keywords: textile, lying and sleeping, settlement, infrastructure, and transport, household

A gometric motif with a “Mon” or family crest in the central panel. Both patterns are applied using the “Kukuri-gasuri” (tie-dye) technique, respectively on the weft, weft, and warp threads (double-Kasuri), in white (natural) reserved on an indigo blue background.

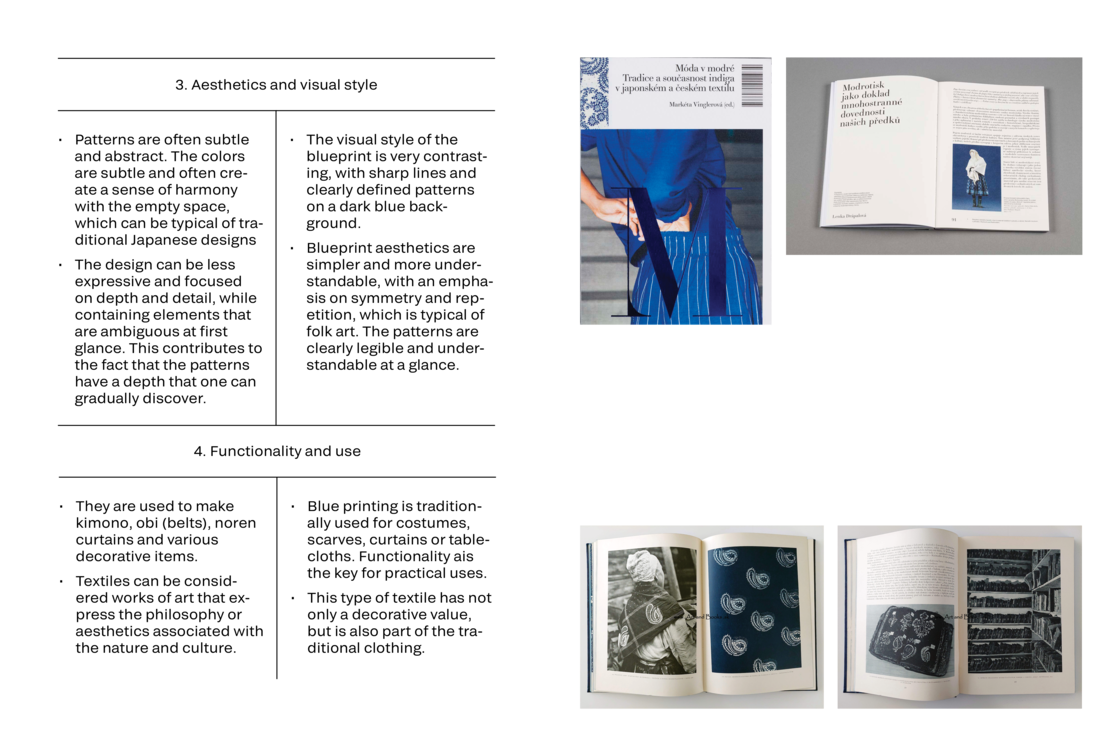

Japanese Ornamental Art

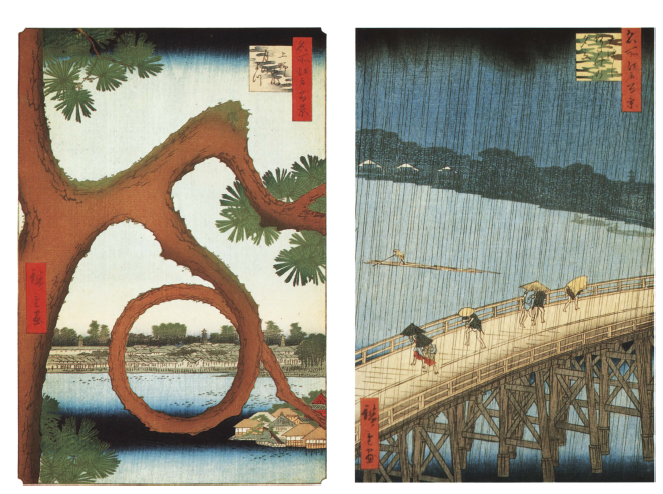

Virtuous art and ingenuity. The patterns are most graceful. "Only those who love their work and find fulfillment in its perfection can truly experience all that they create." Nature should not be imitated but stylized, so as not to break the rule: decoration must remain flat. A genius cannot be enslaved by syntax. Whatever he creates, he does not break the rules; rather, he forms them. Even in extravagance, balance is achieved.

There is a certain charm to Japanese art—the fact that one does not immediately grasp its essence but continues to discover new depths. This quality could never be achieved through simple arrangements of geometric patterns typical of European styles.

In his essay The Critic as Artist, Oscar Wilde noted, "Decorative art is, of all visible arts, the only one that truly creates mood and temperament within us. Color alone, untainted by meaning and unconnected to any particular form, can speak to the soul in a thousand ways. The harmony found in the delicate proportions of line and mass reflects itself in our minds. The repetition of patterns calms us. The marvels of design stimulate our imagination. Within the sheer beauty of the materials used lie elements of culture."

The selection of ornaments for the stage means little by itself. It is through the use of colorful surfaces, shades, and harmonious lines that we attempt to touch the human mind and evoke emotion.

Today, people desire simple objects without complicated forms, yet of beautiful shape, delicate proportions, and quality colors.

Each pattern carries a symbolic meaning:

• Floral patterns (such as chrysanthemum or sakura) symbolize the transience of life and beauty.

• Animals and natural elements (such as cranes and waves) are symbols of longevity, strength and vitality.

• Geometric patterns often represent harmony and balance.

During the Edo (1603-1868) and Meiji (1868-1912) periods, these motifs reflected not only artistic but also social and spiritual values. Such textiles were used for kimonos, which served not just as clothing but as a means to express identity, status, and social roles.

The Japanese also often employed techniques like kasuri (ikat) and shibori (tie-dye), which require high skill and patience. These techniques are part of the concept of “shokunin”—the Japanese dedication to mastery and craftsmanship.

1. The Edo Period (1603–1868)

The Edo period is known as the period of isolation (sakoku), during which Japan limited foreign contacts and focused on internal development. This period is characterized by a strong emphasis on domestic culture, traditions, and craftsmanship. At the same time, textile arts flourished, particularly in cities like Kyoto, where textiles were produced for the nobility, samurai, and wealthy merchant classes.

During this period, various techniques were developed, including:

Kasuri: traditional Japanese textile dyeing and weaving technique, notable for its characteristic blurred or “feathered” patterns. In English, this technique is often referred to as ikat. Kasuri has a long history, with unique styles and methods that set it apart from other fabrics. Is made by partially dyeing the threads before weaving, so that the patterns emerge as the fabric is woven. In kasuri, specific segments of individual threads (either warp or weft) are partially dyed before weaving. The threads are bound or tied in certain areas to resist dye, similar to tie-dye or batik. The dyed sections are carefully planned so that, once woven, they form the desired pattern. This process is intricate, as it requires precise alignment and planning. After dyeing and drying, the prepared threads are woven into fabric. As the dyed threads are woven, they create the characteristic blurred patterns unique to kasuri. The “feathered” edges of the pattern are due to the slight misalignment of the dyed segments during weaving, resulting in a soft, organic look.

Today, kasuri is highly prized and used to create kimonos, clothing, curtains, decorative textiles, and occasionally rugs. Although traditional methods of dyeing and weaving are time-consuming and costly, kasuri retains popularity among lovers of traditional craftsmanship and modern design. Some contemporary designers and artists experiment with kasuri, creating modern patterns and applications that bring this technique into new contexts.

Yuzen-zome: an intricate stencil-dyeing technique allowing for detailed patterns such as flowers and animals.

Shibori: a method of dyeing textiles by binding and folding the fabric, producing unique patterns. Patterns and symbols in Edo period textiles are often delicate and aesthetically balanced, reflecting concepts like wabi-sabi (beauty in imperfection) and ma (empty space). If the textile you are studying contains these elements, it may be influenced by the aesthetics and craftsmanship of the Edo period.

2. The Meiji Period (1868–1912)

The Edo period was followed by the Meiji period, during which Japan opened its borders to the world and began rapid modernization and industrialization. Western influence became an important factor in Japanese art and crafts. The textile industry began to industrialize, and Japan started exporting its textiles worldwide.

This period develope: Hybrid patterns: a combination of traditional Japanese motifs with Western styles and techniques. Western color schemes and new dyeing methods. Industrialization of the textile industry: the beginning of machine weaving and dyeing, which marked the end of fully handmade textiles on a large scale.