This week, I thought about how I could write a different text based on what you saw above. Instead of my own story, I started drafting a piece about a fictional female character who performed as a meddah in the 19th century.

What I wanted to find out was telling the story I wrote and see if it captivates people and create a public space through story telling. Moreover, experience the story telling performance as a performer in a public coffee house. While sitting at a café with my friends, I asked them if they would be interested in hearing a meddah story I had in mind. My insights were like these; they were interested in the story I told and more importantly the story telling environment I created at that moment. They listened with great interest and expressed curiosity about what would happen next. So I decided to work on the rest of the story that I've been writing. For me, it was an opportunity to create a storytelling space and to briefly observe how people engaged with the story and their thoughts on this narrative form. You can find the text of the story shared in the video below.

PERFORMING THE FEMALE MEDDAH: The Male Turkish Traditional Public Storyteller Through a Feminist Perspective

Question: From a feminist perspective, what could a modern female meddah use instead of traditional meddah costumes and accessories?

This week, I worked on how to adapt traditional meddah costumes to my project.

Why do I need to try new costumes and accessories?

Meddah costumes and accessories have been used in the same way for centuries. In other words, when we see someone wearing these costumes, we can immediately identify them as a meddah in our society because this image has become associated with the traditional meddah. In my project, the meddah is different because of the narrative style, the fact that the storyteller is a woman (which is not usual), and the content of the stories (which are about women's rights and gender issues). Therefore, instead of using traditional costumes, I wanted to try different costumes and accessories that would better fit my project and make the relationship between the form and content of the performance more harmonious.

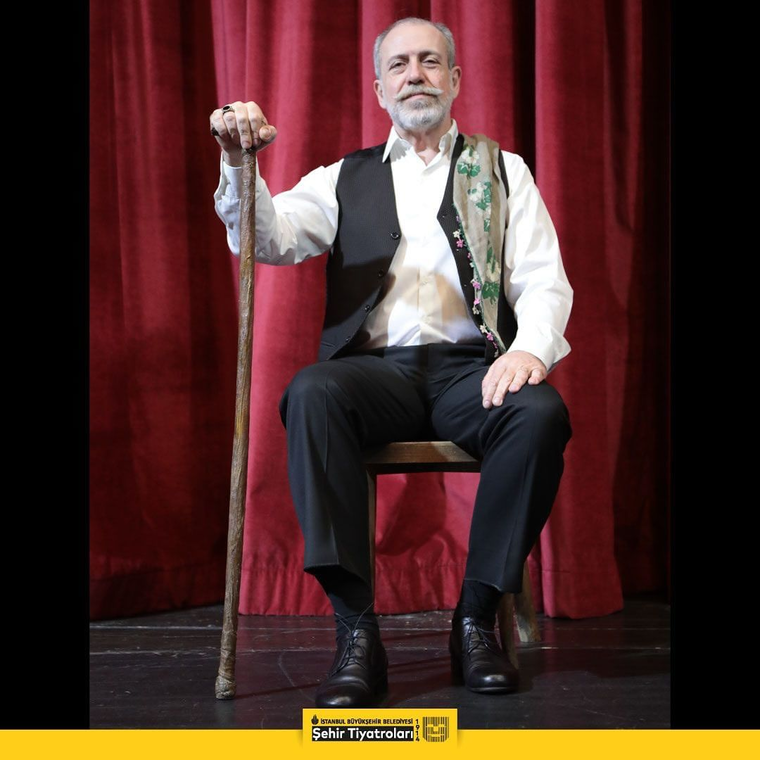

Traditional meddahs usually used to wear a cübbe (a religious robe that Ottoman religious figures used to wear), carry a cane, wear a kavuk (a special hat which most of the meddah used to wear, but as time went by, it started not to appear during the meddah shows), and have a handkerchief on their shoulders. The meddah would hit the cane on the ground three times to draw attention and signal that the performance was starting. The kavuk has its origins in the traditional Turkish theater form called orta oyunu, and it is linked to the character named "Kavuklu'' (which means the one with the Kavuk). Over time, it became a symbolic element of this art, passed down from master to his student (the next meddah after him). This tradition of passing the kavuk is still practiced today and is always given to a male meddah. The handkerchief, on the other hand, is used by the meddah for character transitions. For example, if the meddah is playing a woman, the handkerchief is used like a scarf; if playing a sick person, the handkerchief is used to cover the mouth when coughing, and so on.

Considering these three main accessories and their functions, I worked on the question of what a modern female meddah could use instead of these traditional items.

OCTOBER 14-20

This week I worked on one of my research questions, which is ''How can we create a public space through story telling?''

I wanted to find out if people are open to a dialog with a stranger, if they are willing to listen to a woman who approaches to them and wants to tell a story, their knowledge about Meddah and their ideas about a Female Meddah.

I went to a café and sat down. At the other tables, there were people spending time with their friends, chatting. I approached them and asked whether they knew about Meddah (a traditional Turkish storyteller) and if they would be interested if a woman suddenly started telling stories like a Meddah in a place. I also inquired what kind of stories would capture their interest and how long they would be willing to listen.

I had interesting insights. The answers were very enlightening. The first thing I noticed was that young people generally hadn’t heard of Meddah before. Very few people were familiar with it. However, when I explained what a Meddah is and asked if they would be interested in watching a modern female Meddah, they responded with great enthusiasm, saying yes.

Another insight I had is that people would want to go to a café knowing that this kind of performance would take place, but they wouldn’t appreciate being interrupted while chatting with their friends. As for the duration, they indicated that they could watch this performance for a maximum of half an hour. Another interesting thing was that when a waiter saw me going to different tables and talking with people, he spontaneously came over and said, “You can also go to that table.” It seemed that he enjoyed the conversation environment I had created. And finally I asked the people I talked to if they would like to come see me perform woman Meddah and they were all excited and gave me their mail adresses to be able to keep in touch. I hope they'll show up :)

Below, you can find the audio recordings and the English transcript of the recordings, where you can examine the detailed responses.

When I went to the theater that I work to try on new costumes and accessories, I had some costume and accessory alternatives in mind. For example, the wand you will see below was an accessory I wanted to try instead of the cane. (The reasons and insights that came up after the experience are explained below.) Some accessories and costumes, however, I intiutively wanted to try when I saw them. Even though I didn’t have clear reasons at that moment, for example, there was something that drew me to the color red. (You will see below.) All these experiments and analyses I did, both intiutively and analytically, are listed below.

WHAT IS MEDDAH?

Meddah is a male public story teller that has survived from Traditional Turkish theater to the present day. Today, we can say that the closest performance areas to meddah are stand-ups and one-man shows. Traditionally, Meddah people would go to coffeehouses and sit on a chair with a cane in their hand and a handkerchief to use while imitating later. To attract the attention of the people of the coffeehouse, they would either tap their cane on the ground 3 times or attract the attention of the people with some rhyming sentences, and then begin to tell their story. These stories are about daily events that concern the society, stories from parables, or humorous stories with lots of imitations. In this way, he would both entertain and present a performance from which the public could learn a lesson or just have a good time.

Below is the chronogical overview of my research process.

The page extends downwards and rightwards.

D: Thank you very much. Yes, Meddah. Is this your first time hearing about it?

Woman 1: It’s my first time, right now.

D: May I ask how old you are?

Woman 2: 27. I'm old.

D: No, you're not I’m 39 years old.

Both Women: How can you be 39? You don’t look it at all.

D: Yes, I don't thanks :)Well, this Meddah was basically someone who used to stand up in cafés and start telling stories, and people loved it. They would start with something like “Right, my friend, right.” Perhaps that rhyming stuff sounds familiar to you. I’m curious about something right now. For example, if a woman suddenly came out in today’s cafés and started telling a story like a Meddah, how would you feel? Like, if I suddenly caught your attention and started a story...

Woman 1: I’d listen.

D: Would you? What topics would you like to hear about? I mean... If a woman came here, caught your attention, what would she tell that you’d listen to? What interests you?

Woman 2: For instance, if she talked about something political, I don’t think we’d pay much attention. Because it would feel like those surveyors telling us something, and that vibe would make me turn back to my meal. I’d be interested, but not at that moment. Maybe something we can relate to daily life. Something she could adapt to that moment. But, for example, I would want to know that I was going to that café with this in mind. In a café where I’m going to chat with my friend, we can’t even focus on the music.

Woman 1: It’s like, “We’ve chosen this place because the music was so high in the other one.” We’re already trying to hear each other. Someone telling a story would be spontaneous.

D: But it’s very true. Yes, true.

Woman 2: So, of course, I’d listen. Anything at a high volume would directly catch my attention, and I’d be watching. If the café’s concept is that, I’d go, I’d be curious.

D: Wonderful. Now, to know that you’re going there for that reason, it would be nice. I think that’s right too.Thank you very much for your answers. If you’d like, I can take your email addresses and invite you when I perform this.

Both: Are you going to perform it?

D:Yes.

Both: Where will it be?

Research question: How do I create a public space through storytelling?

Place: Theatre Cafeteria

Participants/Audience: Cafeteria Manager and Colleagues

Accesories/Costumes: A coat, a hat, a cane, three video cameras for recording

Research Question: How can I build audience in a cafe full of strangers through story telling?

How can I encourage people to reflect on and talk about women's issues after the performance?

Place: A cafe in Beşiktaş/İstanbul

Audience: Random customers in the Cafe, friends, friends of friends who heard about the performance and wanted to come

Collaboration: Burçak Çöllü (tambur player)

Accesories/Costumes: Tambur, a hat, a scarf, a witch's broom

Preperations: Going to the cafe and taking the pictures of the space before the performance, printed questions for the audience, pen.

This week, I studied the performance and performance text of Nurhan Tekerek, who is known as Turkey’s first female meddah, as it represents the first example in the field I am working on.

Since I couldn't access the script, I contacted her directly and explained that I was working in the field of female meddahperformance, and asked if she could share the script with me. She kindly sent it to me. Upon my first reading, what immediately stood out was that it was written in a distinctly masculine language.

WOMEN IN THE TEXT

Like in many traditional meddah stories, the script includes many different characters that the performer plays. But the story mainly focuses on male heroes. The female characters are shown as objects of desire, loud or rude women, victims, or people who need help from the male hero. They don’t have a real impact on the story and are written in a simple, one-sided way.

A Feminist Reading of the Characters: A General Overview

The primary male character, Zilli Şıh, is portrayed as a respected and influential man within his community, holding the authority of a patriarchal figure and having three wives. The text states, ''Evlerin arkası O'nu görmek isteyen kadınlarla doludur''. (Zeybek, 1984, p. 23) (The backs of houses are filled with women who want to see him.). This phrase underscores a repressive patriarchal system wherein women are confined to the domestic sphere and excluded from public life.

Safinaz is portrayed as the youngest wife of Zilli Şıh. Within the text, her character is primarily defined by her physical beauty and the desire she evokes in men. She engages in flirtatious behavior with the village carpenter. In one scene, Safinaz inquires about the price of a tray in the carpenter’s workshop. The carpenter responds that he will give her the tray if she shows him her chest. Safinaz complies by revealing her chest and subsequently obtains the tray.

The text here supports a system that treats women as objects by showing the female body as something shared only with a man’s willingness, which keeps male control and female oppression in place.

In another scene, Safinaz convinces her husband to cut down the mulberry tree in their garden by telling him that a male bird has perched on the tree and is threatening her honor. She insists that he must cut down the tree to protect her reputation. Consequently, her husband cuts down the large mulberry tree that has stood for many years—sacrificing the life of the tree solely to protect a woman’s honor from a male bird.

Here, we see how oppressive social norms position a woman’s body as a sexual object that must be protected even from a male bird.

Another female character in the text is Gülnaz. Gülnaz is a widow who comes to Zilli Şıh seeking help because she is constantly having bad dreams. Zilli Şıh tells her that these troubles are happening because she is a widow and insists that she must get married as soon as possible

Here, the idea is conveyed that a woman not being under a man’s authority—in other words, being without a man—is considered a danger to society. This serves as an endorsement of the patriarchal system that demands a woman’s body remain under male control.

At the end of the story, it concludes with the Şıh’s abuse of Gülnaz

(because in patriarchal systems, a widow is seen as a woman who does not belong to any man, her body is viewed as open to the claims of any man.)

and the revelation that his wife, whom he considered very honorable, was flirting with the carpenter, delivering a message about honor through the portrayal of women.

Conclusion

As can be seen, this text—written by a man—is an example of a masculine narrative that portrays women only as objects of desire, helpless figures, or one-dimensional characters. Therefore, although Nurhan Tekerek’s participation in this male-dominated tradition as the first woman can be seen as a feminist act of resistance, the content of the performance itself is still shaped by a masculine perspective typical of traditional meddah storytelling.

My experience as a performer:

- This week I wanted to keep on experiencing telling the story I've been writing. This time, I added the first draft of my text (the one which inlvolves my personel story) and than switch to the second draft I've been writing (the one with the story of a woman meddah who lived in 19th century in Bursa). I added my first draft because I wanted to find out if it is more interesting to capture the attentiton with a personal story and than open the story to a larger one with the woman meddah from 19th century.

- I started asking people if they know about Meddah again. Some of the people that I was sitting with were actors so they knew. But to attract the attention of the other people from the table, I decided to tell my own story first so that they would feel like I'm sharing something special about me and this is not a performance. Because I belive it's important in a performance like this to spark curiosity and invite people into the story so that I can tell the story that I actually want to tell. This beginning part is like a warm up for me and my insight about this beginnings is that it always works to draw attention so that I am planning to keep the first part of my draft in the performance as an openning text. But of course it can change from place to place, I have to decide that moment which is a basic aspect of Meddah; to change the story according to the place and people if needed.

- I realised that when I sing during story telling, it helps draw attention and gives musicality to the performance which I, as the performer enjoy and can have a little break from story telling which is for sure tiring both for the performer and the audience. And it gives me some time to evaluate the energy and attention of the audience and think about how I should go on telling the stories, if I should change them or keep on telling as I wrote them at the first place.

- My other insights were that as a performer these series of performances help me gain experience as a public story teller. So I decided to do these little performances as much as possible while writing the rest of the story. And I've realized that story can write itself according to the reflections of the audience. And I came to the conclusion that maybe I can make an experience which I ask people how they want this story to continue or end. This could be a whole different interactive meddah performance itself.

Research Question:How can I convey a serious issue like domestic abuse against women through a meddah performance?

Are they willing to come again to listen to women's stories and discuss them?

Did my previous performance spark curiosity?

Audience: Same Collegues from the previous experiment

Accesories/Costumes: A wig

Research Question: How can I create a conversational atmosphere and smoothly engage the audience in the performance?

What is the impact of ''tambur'' on this performance?

Place: An art place called ''AndArt''

Audience: Collegues, Friends, Friends of friends

Collaboration: Burçak Çöllü (tambur player)

Accesories/Costumes: Tambur, a hat, a wig, a witch's broom.

Preperations: Wine and snacks for participants, post-its for feedback later

After returning to Turkey from intense weeks in Tilburg, I began planning the next experiment for my artistic research, while also working on the artistic and theoretical reflection for my Period 3 portfolio.

While working on my theoretical reflection, after Period 2, I decided to shift my focus from Western culture to explore feminism within the context of Turkish and Ottoman culture, in order to develop my own perspective.

Reconsidering the props

''Kadınların görünmeyen emeği; cinsiyetlendirilmiş olduğu kadar doğallaştırılmış emek biçimlerinin tamamını, her ne kadar patriyarkal pazarlığı bünyesinde barındırsa da bir tür hiyerarşik ilişkiler yumağı ve aynı zamanda patriyarkanın temel dayanaklarından biridir. Bu çalışmada ise kadının görünmeyen emeği kavramı, 8 Mart 1987 tarihli ‘Feminist’ adlı derginin kapağında yer alan Her şey onun kollarındayken başlar; senin kolların onun bulaşık kabındayken biter ifadesindeki vurguyla özdeştir. Dolayısıyla, ev temizliği, yemek pişirme, bulaşık, çamaşır gibi faaliyetleri kapsayan çeşitlenebileceği ve farklılaşabileceği halde özellikle hane içinde gerçekleştirilen işlerin, gerek tek bir çatı altında toparlanmasını kolaylaştırıcı bir işleve sahip olması gerekse cinsiyete dayalı iş bölümünün yönünü tayin etmesi nedenleriyle, kadının görünmeyen emeği kavramı kullanılmaktadır.'' (Kendir-Gök, 2022, p.83)

("Women's invisible labor includes not only gendered but also naturalized forms of labor. Although it is embedded within the framework of the patriarchal bargain, it represents a complex web of hierarchical relationships and serves as one of the core foundations of patriarchy. In this study, the concept of invisible labor is associated with the message on the cover of the March 8, 1987 issue of the magazine Feminist, which reads: ‘Everything begins when it’s in her arms; it ends when your arms are in her sink.’ Therefore, the term 'invisible labor of women' is used to describe domestic activities such as house cleaning, cooking, doing the dishes, and laundry. Despite the variety and differences among these tasks, they are grouped under this concept because they are typically performed within the household and serve both to facilitate categorization and to define the direction of gender-based division of labor.")

At this point, while making artistic choices regarding the props of the meddah performance, I started reflecting on my decision to use a witch’s broom. The concept of the witch is largely rooted in Western culture, and I realized that I could actually offer a feminist interpretation more grounded in Turkish culture. For this reason, I decided to focus on this prop in my upcoming experiment.

While thinking about how women are kept away from public spaces in patriarchal systems and are seen as the only ones responsible for domestic work, I started to reflect on the meaning of the witch’s broom. In the society I live in today, domestic chores are still primarily assigned to women, limiting their opportunities in the public sphere and deepening gender inequality. Based on this interpretation, instead of using a symbol from Western feminism like the witch, I thought of the traditional broom used by women in Turkish homes. This object can also show the oppression and exclusion of women, and it can bring these issues back into public memory. In this way, I aim to make a reference not to the Western witch figure, but to a symbol from my own culture that represents the silenced woman.

D: Hello, first of all, thank you. Have you ever heard of Meddah?

All: No. No.

D: Okay, so Meddah is a story teller from traditional Turkish theater. Maybe you'll remember when I explain it. A man comes in, hits his staff like this, “Right, my friend, right,” and starts telling stories in a café. And the audience listens to him. Does that ring a bell?

All: Yes.

D: Right? Yes, it sounds familiar. Okay, one question. If a woman were to come today, let's say to a place like this, and suddenly starts telling a story, capturing attention, or maybe sing a song or hit her staff, or do something else, and then start telling a story, would you listen?

All: Yes, yes, definitely.

D: Oh, that’s great. So, what kind of stories would you prefer to hear? What would catch your interest?

Woman 1: Something related to her own past.

D: Oh, nice.

Woman 2: Like a hero story. A heroic story.

Woman 1: Exactly, a story with a result. Something that raises expectations, yes.

D: For example, topics like women's rights or current issues regarding femicides?

Woman 2: Yes, absolutely.

D: Would you ever feel like, “Oh, not this topic again”?

Woman 1: No. If they tell the topic in an interesting way, I mean, if it could relate to daily life, but doesn’t comment directly on femicides, like directly.

D: It would be nicer if it’s a bit entertaining, maybe makes you laugh in between, right? For example, how long would you listen to this?

All: 20 minutes. Like 20 to 30.

D: You’re great, thank you so much, girls.

D: Hello, first of all, thank you. Do you know what Meddah is?

Woman 1: Yes. A little. It’s something related to theater, a character from Turkish theater; I remember it from literature, something like that. It’s like a one-person show.

D: Yes, they used to go to cafés and tell stories. Bravo. By the way, how old are you?

Woman 1: I’m 22.

D: I have a question for you: if you were sitting in a place like this and a woman Meddah came in, I mean if a woman suddenly captured your attention and started telling a story, how would that feel to you? Would you listen? Would such a performance interest you?

Woman 1: At first, I might feel uncomfortable, wondering what she’s doing. I think we wouldn’t perceive it at first. But if the story is good, I’d enjoy it. Yes.

D: For example, what kind of story would catch your interest?

Both: A captivating story, I mean, it doesn’t matter what the subject is as long as it’s told beautifully.

D: If she sang a song in between, would you like that?

Woman 1: If her voice is nice and she sings well, why not?

D: What if she sang Turkish music, would you listen?

Woman 2: For me, the lyrics don’t matter; if the melody sounds good to my ear, I’d listen.

D: What if the storyteller wanted to create an environment where women share their feelings about women’s rights and contemporary issues? Would that interest you, and how long would you listen to it?

Both: It could be interesting, I’d like it, we’d enjoy it. A maximum of half an hour, I think. I agree.

D: Thank you very much for your answers.

I have been thinking the ways of creating a Meddah text shaped around women rights and gender and how to narrate it. As a divorced and queer woman living in this country, the idea of creating a narrative based on my own life story came to my mind. So I started the text in this way. Here is the beginning of the first draft;

Research Question: How can I reflect feminism in Turkish Culture through props?

Place:Kalika Kafe in Selimiye/İstanbul

Audience: Random customers in the Cafe, friends, friends of friends who heard about the performance and wanted to come

Collaboration: Burçak Çöllü (tambur player)

Accesories/Costumes: Tambur, a hat, a scarf, a cleaning broom

Preperations: Going to the cafe and taking the pictures of the space before the performance

Regarding the performance, this time I will start the performance as if I were a cleaner in a café. Then, without creating a hierarchy, I will gradually transition into the actual performance. After the performance, I plan to share the insights I gained, its reflection in the public space, and the audience’s reactions.

'She goes to the busiest café, only her eyes are visible. She starts singing a song. Everyone turns around and wonders, "What kind of voice is this?" The voice is feminine, but he looks like a man. And besides, how could a woman be here? How dare she come into a café and sing songs to us alone? Impossible, they think. Then conversations start. "Show us your face, what are you? Are you a devil or an angel? What is this voice?" they ask. The woman replies, "I had an accident when I was little, I lost my masculinity, my voice couldn't grow, it stayed like this." (laughs and talks: Your reaction is so sweet. )After that, people are saying, "How is this possible? Is there really such a thing?" The woman continues with her song (sings), and everyone stares in awe, completely fascinated by the voice.'' (this is the second draft that I have written so far)

In this video, we see the Meddah entering the coffeehouse, greeting the people, asking about their well-being, and then starting to tell a story.

- This week also, I met a dramaturg named ''Sinem Özlek'' who has a deep knowledge of Turkish Theatre and Meddah and also works for Municipal Theatre İstanbul. She provided me with theoretical insights on how to incorporate feminist and queer theories into my storytelling style and how to structure the plotlines in the stories I want to tell. We discussed how I could improve my two written pieces based on this. We will be in discussions throughout the process of creating the text.

At first glance, this coat is perceived as a men's coat, which, from a feminist perspective, brings societal gender roles to mind. As Judith Butler says in ''Gender Trouble'', cross-dressing can be seen as a way to challenge and disrupt the normative boundaries of gender. And it isn’t just about wearing the other sex’s clothes. It’s also a way of questioning the idea that certain clothes, actions, or traits belong to a specific sex or gender.

Since the theme of my performance is about women's rights and gender issues, this alignment of form and content in my performance becomes evident.

TRADITIONAL MEDDAH

Wears a hat(kavuk), holds a cane

Male performer and male audience

Stories that entertain and provoke thought about social issues, ethical values.

Hits the cane 3 times to the ground. (Authority figure

Higher than the audience and in the centre

A tool to take a break from the story and keep the attention fresh

Audience would know that Meddah was going to come for performance

''There was a meddah, do you remember? You know, one who suddenly appears and starts telling stories, launching into rhymes and bursting into song. How wonderful it would have been to experience those times! Maybe I would have become a meddah myself. But then again, they were always men. As a woman, I probably wouldn’t have had much of a chance. Even if I tried to imitate a man, my voice would be too high-pitched to pass. Have you ever seen a female meddah? There was one who tried back in 1940. In Bursa. She covered her head with a shawl, leaving only her eyes visible, and entered the busiest coffeehouse in the village, starting a deep gazel… (sings) The woman said, "I lost my manhood in an accident at a young age, before I even grew up. That's why my voice remained like this, like a woman's voice... That's what ı have written for now...'

It's a cultural knowledge that Meddahs used to wear a "cübbe" (robe) because in the Ottoman Empire, religious figures wore it as a sign of respect and wisdom. The tradition of meddahs wearing a cübbe comes from this. It helped them stand out and get attention, while also creating an image of dignity and wisdom.

When I thought about what I could wear instead of a traditional robe as a female meddah, I saw this masculine-looking men's coat that was a few sizes big for me in the theater's costume storage. Intuitively, I wanted to try it on. When I thought about why I felt that way, I realized that the meddah figure I was working on, had always been a man in my mind. And even though I am working on a female meddah, I felt the need to look like a man. And this feeling was because of the ''gender roles'' that I have been thought. So, I wanted to try an experiment with this feeling. And interesting insights came out of it.

I visited the venue where the performance will take place in order to better understand how to position both myself and the audience within the spatial context, and to observe the potential layout and flow of the audience. Although I had previously spoken with the venue owner over the phone, this visit allowed me to present the project in person and discuss specific spatial requirements. The video was recorded to share the spatial characteristics of the venue with the musician I am collaborating with.

Are Cafes Public Spaces?

As mentioned in Ahmet Yaşar’s article "Ottoman City Spaces, Coffeehouse Culture'', coffeehouses in the Ottoman Empire have been public spaces that shape social relations, create an environment for cultural formation and transformation, and reflect the societal changes of the time since their first appearance. They have even been places where people could create a will against the government and make their voices heard. In fact, coffeehouses were closed for a period because of this.

Ekrem Işın, in his studies on daily life and the relationship between culture and space in Istanbul, refers to coffeehouses as the "godless temples" of Istanbul. He points out that these spaces have made significant contributions to social history and culture.

Sociologist Sibel Kalaycıoğlu, in her work "Culture, Space, and Public Sphere", examines the cafés in Istanbul within the context of public space. According to Kalaycıoğlu, the transition from traditional coffeehouses to modern cafés is almost proof of how the social and cultural structure has evolved. These cafés are still places where people gather to relax and have a good time, but they are also places for cultural production, artistic communication, and cultural interaction. In other words, the impact of traditional coffeehouses on public space continues in today’s modern cafés. People from all social classes come together here and interact, which leads to a transformation and interaction in the city’s culture, art, and even education.

When we look at Habermas, who introduced the theory of the public sphere, he defines the public sphere as a place where individuals come together to discuss social issues, a place where public opinion and public will are formed. Here, individuals can freely express their opinions, discuss political and public matters, and create a diversity of ideas.

Therefore, cafés can be considered a public space in the sense that they are places where individuals can come together, exchange ideas, discuss social issues, and contribute to cultural and artistic transformation and interaction

''From Central Asia to the Arab and Persian regions, and from there to the Ottoman Empire… Our ancient storytelling tradition, meddahlık, which traveled from East to West, has been revived in the 21st century in Turkey — this time by a woman. This woman has used one of the most significant forms of our oral literature to tell her own existential struggles and those of other women. She has taken back this narrative form, once performed only by men, and reclaimed it. It is as if she has reversed time, reinterpreting the old and the new through her own words. She has taken theater out of its conventional space and placed it right in the middle of our lives — in a neighborhood café — to build it anew.

With her headscarf and cap, she presents the complete look of a traditional meddah, while the old storyteller’s cane turns into a witch’s broom in the hands of Dolunay Pircioğlu, offering a symbolic salute to women's resistance against a male-dominated world and their presence in society. This salute is not given through mere visuals or straightforward narration, but through a portrait of a proud yet melancholic woman from the past, drawn with the accompaniment of Tamburi Buçak Çöllü and classical Turkish music that draws the audience into the story.

By the end of the performance, it leaves us all in deep thought and with a lingering sense of artistic beauty. With her brilliant idea, courage, performance, approach, and writing, Dolunay Pircioğlu is sure to become a name we will hear much more of in the future.''

The Questions I Prepared:

1)What thoughts and feelings are you left with tonight?

2)What other kinds of stories would you have liked me to tell?

3)Do you think our society needs a woman meddah today?

These questions were actually based on my research questions — the ones I explore throughout my project. The common points in the audience’s answers were that it is important and necessary for women’s stories to be told by a woman; that the performance happening as a surprise was, in a positive way, very unexpected and very enjoyable; and that it deeply moved the audience. People said they felt emotional, sometimes angry, but also had fun. The music and songs added another layer of value to the performance. Many mentioned that more women’s stories should be shared, that this performance should reach more people and places, and that they were curious about what happens next in the story. Especially hearing such positive feedback from people I had never met before gave me even more confidence in my project.

Based on the insights I gained from collecting feedback after my previous experiment, this time I focused on what I wanted to learn from the audience. I prepared three questions for them to answer after the performance. At the end of the performance, I briefly explained that I’m doing research on a modern female meddah, and that I believe their thoughts and feelings will help improve my project. Then I handed out the papers with the questions.

Collecting Feedback

With the experience I gained from my previous experiments, this time I brought post-its and pens with me to collect feedback from the audience. After the performance, I asked them to give me a gift, explaining that the gift could be a critique, a suggestion, a comment, or a connection. (This feedback exercise was done during the intense week at school in January, and I adapted it to my experiment.)

''I think you can keep the broom :).''

''After mentioning a date like 1930 in the introduction, it might be helpful to provide historical information in 2 or 3 places throughout the text.''

''The story is real, the narrative is real, the voice is real, and I'm curious where the story will evolve to.''

''I never lost my curiosity. More men should see this.''

''Listening to a woman's story from a woman's perspective is beautiful. Striking and impactful. May the story and your path, Dolunay, be open.''

''We should have songs to accompany us to today. "Gül (Rose) Meryem" would be a great slogan. There shouldn't be too many sad parts in the tavern.:) Do it in the tavern.:)''

''It can be connected to modern women's issues, from mobbing to harassment.''

''It was very impactful. We deeply felt the story. I would love to hear more stories from today as well.''

Analysis of the look

The witch's wand we see here, when evaluated in both historical and feminist contexts, points to women's rights, the weakening of women, the silencing of women, patriarchy, and patriarchal systems.

During the medieval period, approximately 50,000 people were sentenced to death and executed by burning under accusations of witchcraft. As ''Cemal Hüseyin Güvercin'' explains in his article called ''Witch Hunt'' that witches were mostly women. Particularly elderly women who had gained experience and autonomy, and widows who had escaped male control, were seen as the prime candidates for witchcraft. Sometimes, excessive beauty, or ugliness, or having great physical strength, or even walking alone at night, were considered signs of witchcraft.

As feminist avticist and writer ''Sylvia Federici'' says, during the witch hunts, women who went against social rules or acted independently, especially in terms of their sexuality, were often seen as dangerous to society. Federici argues that these accusations were not just about punishing individuals, but about controlling women’s power and independence. Religion and misogyny played a key role in creating these accusations, making them more about enforcing social control than about the women themselves.

According to Federici, in this way, the witch hunts were part of a broader system of maintaining control over women, their labor, and their role in society. Federici shows that challenging sexual norms and defying social order was seen as a threat, not only to individuals but to the stability of society.

Federici explains how the witch hunts destroyed some of the rights and practices women had. For example, they took away women’s traditional medical knowledge, forced them to fit into male-dominated family structures, and erased a more balanced view of nature. Before the Renaissance, there was a more equal and respectful understanding of nature and the female body, but the witch hunts destroyed this view and tried to control women even more.

And according to academician ''Suna Arslan Karaküçük'', Witchcraft and feminism have both been shaped by patriarchy. Witchcraft is older than feminism. Both movements, instead of following traditional roles for women like being a mother, wife, housewife, or teacher, stand against patriarchy. She explains that in ancient Rome, women were accused of being lesbians and engaging in adultery, which led to widespread executions. The true reason Jeanne d'Arc was accused and burned at the stake in 1412, after being blamed for France's military loss, was because she dressed in men's clothing, rejected male partners, and was accused of witchcraft. The system that created the concept of witchcraft rests on two main pillars: sexist/patriarchal power and religious authority.

In ancient Turkish culture, there is very little information about witchcraft, but there is a belief in Bökü/Bögü (magic) associated with female shamans who could predict the future and communicate with the gods. She says that Witchcraft is a form of female gender identity created through negative discrimination.

In my project, I approach a practice of story telling which is traditionally male and revive it as a woman. And this approach makes it a form of rebellion against patriarchy. The project also covers topics such as women's rights, the societal and state pressures women endure, women's sexual freedom, and the persistent issues of being a woman that have remained unresolved for centuries (at least in my country). Because of these reasons, I believe that a witch image in this costume experiment is very effective and relevant to my project.

''TAMBUR'' and it's relation to FEMINIST STORYTELLING

The tambur is an instrument that holds an important place in Ottoman court music and is used in Classical Turkish Music. As Bülent Aksoy also stated in his book "Conversations on Ottoman/Turkish Music" it began to be used in Classical Turkish Music from the 17th century.

As known from researchers on Ottoman culture such as Metin And (Arts and Entertainment in Ottoman Culture) and other sources, the tambur is considered a male instrument. It was taught to male students in music schools, and there is no record of women playing the tambur. When examining the relationship between musical instruments and gender in the Ottoman period and Turkish music, as Banu Beşiroğlu also states in ''Gender and Women Musicians in Ottoman/Turkish Music'' the tambur was considered suitable for men, while women were directed towards more ''delicate'' instruments such as the oud.

The physical characteristics of the tambur—its long neck and large body—also symbolize the male domain. In a conversation I had with Burçak Çöllü about the tambur, I learned from her that there is a smaller version called the zenne tambur (zenne means ''woman'' in Ottoman Turkish) designed for children, with a shorter neck and it's easier to play as a woman because of the physical conditions.

When she told me that she could play the zenne tambur if I wished, I chose not to. This was because the tambur, as an instrument traditionally played exclusively by men and representing the male world, would become an act of defiance against patriarchy and tradition when played by a woman in my project. And a narrative form historically granted only to men being taken up by a woman holds great significance in the feminist storytelling context of my project.

Welcome back, everyone. Now, I’m going to tell you about Asude’s mother.

When Asude was just five years old, her mother committed the greatest sin on earth—one that would cost her life. She didn’t put enough salt in the food… Since that day, Asude has always poured salt onto her meals. By the time she leaves the table, the entire table—and even the floor—is covered in salt. And every time she stands up from a meal, she sprinkles a pinch of salt over her head, so that bad luck won’t follow her. Though, honestly, I don’t know how much worse her luck could get because of this salt issue.

Meryem was a beautiful, lively, slightly plump woman. Despite her poverty, despite everything, she remained cheerful. Her husband was deeply in love with her mother. But her mother didn’t love her father the same way—after all, she was just a child. What did she know about love? When she heard she was getting married, she thought, “Oh, finally, the nightmare is over. I’m getting out of this house.” She was married off at 13—still a child. Later, people said, “Poor woman, she had such a tragic fate.” They said, “She escaped her father’s beatings only to die at the hands of her husband. You can’t escape fate.” People always blame fate for everything. That’s just how they are.

One day, while she was in the kitchen, preparing a meal—completely unaware that this meal would lead to her end—she was humming a song. And, as always, Asude was watching her mother with admiration. *(Song 1:She takes on the role of the mother, using an accessory, and starts singing… “Aman Avcı…”)

Suddenly, the door burst open with a kick.

“I’m home! Set the table!”

All the joy in the room was shattered in an instant. That’s how it always was for Meryem. Doors in her life either flew open with a kick or creaked open slowly in the dead of night. She thought to herself, “At least the kicked doors are better.” When she was a child, it was her father who opened doors in the middle of the night. Those doors took away her childhood, her womanhood. The doors her husband kicked open took away her life.

What can we say? Meryem had a cruel fate.

Meryem used to say, “My father loves me. This is just his way of loving me…” (a quote from an interview)

But then she wondered, “If this is love, why don’t I like it? Why does he tell me not to tell anyone? If it’s love, why should it be a secret?”

One day, she decided to tell her mother.

“Mom,” she said, “Dad comes into my room at night. He says he loves me, but I don’t like it. Tell him to stop.”

Her mother stared at her.

“What are you saying?” she said. “That’s nonsense. Your father loves you—what more do you want? You just have to stay quiet and do as he says. He’s your father.”

“But, Mom…”

“No buts,” her mother said firmly. “I don’t want to hear such nonsense again. If you talk like this, he might throw us out on the streets. Do you want strangers to ‘love’ you instead?”

Meryem fell silent. Maybe it was just a dream. If even her mother didn’t believe her, who would? She pulled the blanket over her head, squeezed her eyes shut. But that dream became a nightmare—one that filled her room every night. She couldn't tell anybody. (Song 2: A song enters... ''Kimseye Etmem Şikayet'')

Unfortunately, it was real.

Meryem’s nightmare was real. And it continued every night until she turned 13.

She hated the nights. She hated her father. She hated her mother. But most of all, she hated herself. She felt ashamed. “It must be my fault,” she thought. “I must have done something wrong.”

Every child blames themselves, don’t they?

“It’s my fault. This is my fate. I have to live with it.”

The nights stretched on, longer and longer, until Meryem’s whole life became one endless night. *(Song 3: A song plays… “Olma Sabah…”)

The performance text in English (The continuation of the story from the 5th and 6th mini performances)

Analysis:

- I found out that one of the element of creating a public space through story telling is capturing the attention, in other words, how to begin and the other one is the stories being told. In both experiments I started with a question. It's a good way to draw attention. In this experiment what's different than the previous one was, after the question I went on with a personal story first. It worked better at drawing the attention compared to the previous one. So, starting with a personal story could be an element of creating a public space.

- Changing the stories in that moment according to the place's or audience's energy or attention, in other words ''improvisation'' is an ingredient in creating public space through story telling.

- Using music in the story telling increases the excitement of the people. So music is an important ingredient.

- Repeating these experiments is helpful to collect information about finding out the possible answers to the question ''How to create a public space through story telling''. And asking people how they would like the story to go on or end could be a new experiment to work on this research question.

We see a butterfly shaped mask here. A mask, in its simplest form, represents hiding and being hidden. As Beauvoir says in ''The Second Sex'' that women are placed as the "other" in society, and this role is imposed on them by society. She talks about how women wear "masks" to meet society's expectations, meaning they take on gender roles.That connects with the woman in my story who dresses as a man, hides her sexual identity and secretly performs as a meddah, and it helps me identify with her as the performer telling this story.

And it's known that ''butterfly'' symbolizes change, transformation, freedom and enpowerment. That aligns with the concept of my project, which involves addressing a traditional male practice and transforming it into a female practice.

Considered together with the coat, the contrast they create causes confusion about learned gender roles. The coat is masculine, while the glasses are feminine. The fact that the learned things about how a woman and a man should get dressed don't appear as expected, and the confusion this causes, will have a positive effect in terms of attracting attention and raising questions about gender roles.

I wanted to create an image that would attract attention by adding a feminine accessory to this masculine-looking coat, intuitively. I was curious about what kind of image a woman would create, hidden behind red butterfly shaped sunglasses and a large coat. In the text I wrote, I talk about a woman who dresses as a man and hides her identity to perform as a meddah. This image instinctively made me feel like that woman. If I were in a café, a woman appearing with this costume and accessory combination would definitely catch my attention. Since this is an important step in my project (to grab people's attention before I can start telling my story), I wanted to explore this costume-accessory combination.

Creating a conversation environment to start the performance, audience building and spatial arrengament:

Before starting his performance, Meddah would ask how everyone was doing and chat a bit. To keep this element and create more of a feeling of chatting rather than the sense of a play starting, I begin with a sentence as if I’m having a conversation. This way, the people in the space are slowly and unknowingly drawn into the performance and shift into the role of the audience.

Meddah would sit in a higher spot, placing himself at the center and above everyone else. If we see this as a commanding, masculine, and patriarchal setup, I chose to begin on the same level as everyone. In this way, I positioned myself as equal to others, rather than looking down from a higher position.

Character imitation:

One of the elements of Meddah is his ability to transform into various characters while telling a story. Here, you can see that I take on the role of a fictional character I’m about to tell a story about, using a hat instead of the traditional hat (Kavuk). This fictional character is a woman from the 19th century who dresses as a man to perform as Meddah. Therefore, I place the character on a higher spot, just like a traditional Meedah would, and choose a masculine posture for her since she acts like a man. So that I seperate the story teller me and the character I imitate.

Music Usage:

Props

What first stands out here is Tekerek’s interpretation of the prop. Instead of the traditional long stick known as the asa, commonly used by meddah performers, she uses a traditional Turkish instrument called the tef (tambourine). She uses this instrument both to capture attention and to create transitions between parts of her speech. In terms of costume, she chooses casual, everyday clothing. The performance space appears to be an indoor venue with invited guests. I will gather more information about these choices when I meet with her for an interview.

Performance Language

As traditional meddah does, Tekerek uses rhyming words in her storytelling instead of a daily language.

Music

She sings acapella well known songs in her performance and invites audience to sing along.

'Me: Do you know what a "meddah" is? You probably do.

Woman at left: A meddah is a storyteller, someone who tells stories.

Me: I’m saying, if a woman today got up in a café or a bar, and started telling a story saying "Hak dostum hak!(The traditional starting words of meddah)" or in a more modern way "Hello, people," would it catch your attention? Would you listen?

The man: It depends on the girl.

Me:What kind of girl would you expect?

The man: I’m not sure now, asking like this (laughs).

Me: I have a tattoo, it says "home." I got it done before I went to Holland, with my girlfriend. But when I went to Holland, I had neither a home nor a girlfriend. So, the tattoo "home" was on a homeless woman, me. (A waiter comes to take an order).

The man: My meddah, continue please!(laughs).

The woman: Anyway, let’s not break the flow, keep going.

Me: Then I thought, meddahs used to tell stories like this, and people would gather around to listen with interest and excitement. Then I thought to myself, I wish I could be a meddah too, but I’m a woman, and all meddahs were men. Then I remembered a story from the Ottoman period, about a woman who dressed as a man and became a meddah. Her name was Zühre Ana. She was a woman.''

You know, I've been talking about becoming the first female meddah (traditional Turkish storyteller), right? Well, turns out, there actually was a woman like that. Back in 1930s, in Bursa. She would disguise herself as a man and go to coffeehouses to perform her storytelling. And she did it all her life, never getting caught. Her name was Asude Hanım.

One day, she put on her hat, pulled it down low over her face, and walked into one of the busiest coffeehouses in Bursa. She hit her cane to the ground three times, and began to sing her tale… (Song 1: Güzel bir göz beni attı)

A man stops the song yelling; ‘’What kind of a voice is that? Are you a woman or a man?! Tell us!’’

Of course, everyone turned to look, wondering what kind of man this was, with such a voice, such a sound. They couldn’t imagine that a woman would have the courage to come into a coffeehouse full of men and sing... It was unheard, how bold, how would she dare! It was impossible back then for a woman to go to a coffeehouse alone and start singing. They would have silenced her right that moment! Though I don’t know how much we can tolerate hearing a woman’s voice nowadays too, but, anyways… While they were thinking, "What is this woman doing here, what’s this voice that sounds like a woman’s’’ But they look at her – tall, with the build and strength of a man... but that delicate, fine voice didn’t fit the appearance of a strong man. Then, whispers started, murmurs: "Who are you, sir? Come on, show us your face, are you a woman or a man, a devil or an angel..." She answered, "I lost my manhood in an accident when I was young, before I even grew up. So, my voice didn’t grow up to be a man... And I have scars on my face from that horrible accident which I’m embarrassed and don’t want to show… Please gentlemen…. Believe me… This voice of mine is the only thing I have now… So please… Let me sing my stories to you… If you don’t like it, just stop me… Just say leave now and I’ll leave… (waits… silence…keeps on singing)

They listened. It was interesting to see a creature like that… A man with a voice of a woman… So different than they know, see and imagine.

Anyways, she wanted to tell... maybe not her own story, but her mother's story, the story of the neighbor's daughter... The story of the neighbor's daughter whom she was madly in love with but could never be with… She wanted to tell how she loved her… How she had to run away from her… How hard it was to have to run away… (Song 2: ‘’Kaçsam bırakıp’’)

You want to know her story?? Then, I invite you to come here again next Sunday, this time. Thanks for coming. Hope to see you soon.

MODERN MEDDAH

Holds a witch's broom

Female performer and mixed audience

Women stories

Creates a warm, conversational environment

The same level with audience and puts audience in the centre

Using songs composed by women or involves women stories.

Involves a woman musician who plays Tambour which is known as an instrument always played by men.

The performance can be pop-up, unexpected or unannounced

Props

In this performance, I conducted research on props and costumes. During the week of May 26 – June 1, while discussing the design for this experiment, I reflected on how the witch’s broom has a stronger presence in Western culture.

I noticed that the concept of a "witch" doesn't really have a direct equivalent in Turkish culture. Thinking about what a witch might correspond to in Turkish culture, I considered the Middle Ages when women were burned as witches in Europe. I wondered what happened during the Ottoman era. In the Ottoman Empire, women were often confined to their homes and isolated from public life, which was a way of erasing them socially. They were responsible for all the household chores—taking care of children, cooking, cleaning—all day long, and they were held accountable for these domestic duties. So, in a way, the equivalent of witch-burning in Ottoman culture was confining women to the home, excluding them from the public sphere, and holding them responsible for housework.

Costume

As part of my design process for this performance, I intentionally chose a costume that reflects the everyday clothing of contemporary women. Rather than creating a theatrical or exaggerated outfit, I wanted the character to look like someone we might see on the street today. This decision was rooted in my desire to ground the performance in reality and to highlight how the themes of domesticity and gender roles are not confined to the past—they are still deeply present in the lives of many women today.

Through this minimalist yet intentional design approach, I hoped to create a space where the audience could confront the familiar, and perhaps question the societal norms that shape women’s daily experiences.

Let me tell you the story. I applied to this school. You know, I was getting bored at the City Theatre, always the same things, the same places. I wanted to step outside of theatre. Then I found this department. But I had to submit a project, so I thought of the concept of a meddah (traditional storyteller), and I said, why not create a female meddah? (laughter, conversations, jokes). Then suddenly, I found myself researching a female meddah from a feminist perspective. I thought, great, I’ll be the first female meddah, it’ll be so cool. But then I realized, I can’t because someone has already done it (laughter). Never mind, I’ll be the second one (laughter, jokes). Anyway, I started researching this woman. It’s really crazy. This woman performed as a meddah, dressed as a man, until she died. (At this point, I begin to transition into the story of Asude, a fictional character I created, with music)Back in 1930s, in Bursa. (Tambur enters) She would disguise herself as a man and go to coffeehouses to perform her storytelling. And she did it all her life, never getting caught. Her name was Asude Hanım.

One day, she put on her hat, pulled it down low over her face, and walked into one of the busiest coffeehouses in Bursa. She hit her cane to the ground three times, and began to sing her tale… (Song 1: Güzel bir göz beni attı)

"Who are you, are you a woman or a man? Take off your hat so we can see your face!" voices started rising in the middle of the song.

Of course, everyone turned to look, wondering what kind of man this was, with such a voice, such a sound. They couldn’t imagine that a woman would have the courage to come into a coffeehouse full of men and sing... It was unheard, how bold, how would she dare! It was impossible back then for a woman to go to a coffeehouse alone and start singing. They would have silenced her right that moment! Though I don’t know how much we can tolerate hearing a woman’s voice nowadays too, but, anyways… While they were thinking, "What is this woman doing here, what’s this voice that sounds like a woman’s’’ But they look at her – tall, with the build and strength of a man... but that delicate, fine voice didn’t fit the appearance of a strong man. Then, whispers started, murmurs: "Who are you, sir? Come on, show us your face, are you a woman or a man, a devil or an angel..." She answered, "I lost my manhood in an accident when I was young, before I even grew up. So, my voice didn’t grow up to be a man... And I have scars on my face from that horrible accident which I’m embarrassed and don’t want to show… Please gentlemen…. Believe me… This voice of mine is the only thing I have now… So please… Let me sing my stories to you… If you don’t like it, just stop me… Just say leave now and I’ll leave… (waits… silence…keeps on singing)

They listened. It was interesting to see a creature like that… A man with a voice of a woman… So different than they know, see and imagine.

Anyways, she wanted to tell... maybe not her own story, but her mother's story, the story of the neighbor's daughter... The story of how she fell in love… How she had to run to survive… How hard it was to have to run away… (Song 2: ‘’Kaçsam bırakıp’’ means ''If I could run away'')

Now, shall we rewind and go to Asude's childhood? Yes? Okey...When Asude was just five years old, her mother committed the greatest sin on earth—one that would cost her life. She didn’t put enough salt in the food… Since that day, Asude has always poured salt onto her meals. By the time she leaves the table, the entire table—and even the floor—is covered in salt. And every time she stands up from a meal, she sprinkles a pinch of salt over her head, so that bad luck won’t follow her. Though, honestly, I don’t know how much worse her luck could get because of this salt issue.

Meryem was a beautiful, lively, slightly plump woman.She was just... well, big-breasted. Unlike some people... (Looking at her own breasts.) Maybe like hers . (Shows someone from the audience) Despite her poverty, despite everything, she remained cheerful.

Those who knew her would say, "Meryem, don't you ever have any worries? You’re always smiling." But in reality, Meryem was afraid. She feared that if she didn't smile, all her secrets would be exposed. That's why she always smiled. She hid her secrets behind her smile. Her husband was deeply in love with her mother. But her mother didn’t love her father the same way—after all, she was just a child. What did she know about love? When she heard she was getting married, she thought, “Oh, finally, the nightmare is over. I’m getting out of this house.” She was married off at 13—still a child. Later, people said, “Poor woman, she had such a tragic fate.” They said, “She escaped her father’s beatings only to die at the hands of her husband. You can’t escape fate.” People always blame fate for everything. That’s just how they are.

One day, while she was in the kitchen, preparing a meal—completely unaware that this meal would lead to her end—she was humming a song. And, as always, Asude was watching her mother with admiration. *(Song 3:She takes on the role of the mother, using an accessory, and starts singing… “Bir Güzel Gördüm…”)

Suddenly, the door burst open with a kick.

“I’m home! Set the table!”

All the joy in the room was shattered in an instant. That’s how it always was for Meryem. Doors in her life either flew open with a kick or creaked open slowly in the dead of night. She thought to herself, “At least the kicked doors are better.” When she was a child, it was her father who opened doors in the middle of the night. Those doors took away her childhood, her womanhood. The doors her husband kicked open took away her life.

What can we say? Meryem had a cruel fate.

Meryem used to say, “My father loves me. This is just his way of loving me…” (a quote from an interview)

But then she wondered, “If this is love, why don’t I like it? Why does he tell me not to tell anyone? If it’s love, why should it be a secret?”

One day, she decided to tell her mother.

“Mom,” she said, “Dad comes into my room at night. He says he loves me, but I don’t like it. Tell him to stop.”

Her mother stared at her.

“What are you saying?” she said. “That’s nonsense. Your father loves you—what more do you want? You just have to stay quiet and do as he says. He’s your father.”

“But, Mom…”

“No buts,” her mother said firmly. “I don’t want to hear such nonsense again. If you talk like this, he might throw us out on the streets. Do you want strangers to ‘love’ you instead?”

Meryem fell silent. Maybe it was just a dream. If even her mother didn’t believe her, who would? She pulled the blanket over her head, squeezed her eyes shut. But that dream became a nightmare—one that filled her room every night. She couldn't tell anybody. (Song 4: A song enters... ''Kimseye Etmem Şikayet''Means ''I can't tell anybody'')

Unfortunately, it was real.

Meryem’s nightmare was real. And it continued every night until she turned 13.

She hated the nights. She hated her father. She hated her mother. But most of all, she hated herself. She felt ashamed. “It must be my fault,” she thought. “I must have done something wrong.”

Every child blames themselves, don’t they?

“It’s my fault. This is my fate. I have to live with it.”

The nights stretched on, longer and longer, until Meryem’s whole life became one endless night. *(Song 5: A song plays… “Olma Sabah…”Means ''Let it not be morning'') (stops the song saying;)

By the way, speaking of Canan (means ''lover'')… While Asude was living in that ruined house, one day, the doorbell rang. "Hmm, who could be knocking on my door?" she thought. She got scared and hid behind the door without making a sound. The doorbell rang again. Then a voice. "My mom sent food, I’m going to give it to you if you open the door." Asude was starving to death, and in her excitement, she opened the door, (Tambur enters) but no words came out of her mouth. She froze, her mouth hanging open. Her stomach was churning, probably because of hunger, she thought. Her throat and ears were burning, her vision was blurry, and she was about to faint. "Hello," said the girl. She had dark skin, thick hair, like a thick rope that fell from her shoulder. She wasn’t like me. Her lips were like meatballs. Her eyes were squinted, as if they were sinking into Asude’s soul. "Enjoy your meal," the girl said. "By the way, my name is Feraye..." (Song 6: Feraye) (The song continues and she says) If you'd like to learn Feraye's story, let's meet at our next gathering friends! So, altogether we sing! (Invites people to sing) Until next time! Bye! (Hops on her witch broom and leaves)

The performance text in English.

It’s a combination of the two stories I told in experiments 6 and 7. When told separately, they are two different stories, but actually, the story in experiment 7 is a continuation of the story in experiment 6.

How did I start the performance? How did I build the audience?

What was different than the previous performance?

Since the audience in front of me was made up of people I both knew and didn’t know—some aware of the performance, some unaware—I couldn’t have started with the story of how I got into my master’s program like I did last time. It wouldn’t have captured their attention.

That’s why I decided to start with a song. Music is a universal language that speaks to everyone and touches emotions. I wanted to draw the audience in with the song, create a warm, casual, conversational atmosphere. From there, I would ease into the actual performance.

Just like Jacques Attali explains in Noise: The Political Economy of Music,music breaks silence and passivity. It creates an invitation to participate. In public spaces, music claims space, demands to be heard, and helps form a public sphere. According to Attali, music can even disrupt the order of authority.

Also, in her article titled "The Physiological and Psychological Role of Music in Performance," Selin Küpeli Oyan states that music is a highly important tool in a performance for establishing a connection with the audience, creating an atmosphere, and drawing attention.

This was different from the traditional meddah style.

In traditional meddah, as we know from the written sources such as ''Turkish Theatre History'' by Metin And, when the performer hits the cane on the ground three times, people understand that the performance has started, and they usually don’t approach or interrupt.

But my goal was different.

I wanted my friend to feel comfortable enough to come close if she wanted to — and feel relaxed, like they could take any place they liked.

So I needed to start the performance in a gentle, warm way, more like a conversation.

At that moment, my friend showed me a photo, and I said, “Wow, that’s great! Okay, do you know this song?” — and I started singing.

She said, “No, I don’t,” and quietly went back to their seat. At that moment she must have understood that the performance was about to begin.

At first, when people heard the music and my singing, they turned around and looked.

The song I chose was from Classical Turkish Music, and it was about a singer named Eftelya, one of the first female singers in the Ottoman Empire.

When I noticed people looking at me, I asked, “Does anyone know this song? If you do, feel free to join in!”

After the song ended and people started applauding, I continued the conversation by asking,

“Does anyone know the story behind this song?”

Then I laughed and said, “Oh, I feel like a meddah now! You know, those storytellers in old coffeehouses. Do you know them?”

There was a friend of mine who’s a literature teacher, so I looked at her and said,

“Teacher, you must know this — would you like to tell us a bit?”

But I saw she was a bit shy, so I quickly continued talking and said,

“Did you know there was only one female meddah in history?”

Then I started telling the story of Asude. So the I connected to the same story that I've played at the previous performance, 8th experiment.

After my last performance, I wanted to perform in a café where there are random people, so I could reach more people. While I was looking for a place like that, my sister told me there is a café in her neighborhood that might be open to this idea. So I went there to talk to the owner and see the place. I took the photos of the place so that I would be able to plan where I would place myself and how I could use the space. The owner said he completely supports the idea, and we agreed on making the performance after 2 days.

In this video, we see an example of the Meddah incorporating music into his performance. In the song he sings at the beginning, he again mentions that it is time to tell a story, and after the song ends, he begins to tell the story.

''The moment I give a short explanation and give the audience the questions I prepared after the performance''

Literature:

Yaşar, A. (2005), ''Ottoman City Spaces-Coffeehouse Culture'' Türkiye Araştırmaları Literatür Dergisi, Cilt 3, Say› 6

Işın, E. (2005), ''Public Space of Istanbul''

Kalaycıoğlu, S. (2004), ''Culture, Place and Public Space''

Habermas, J. (1962), ''The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere''

Literature

Kendir Gök, Y. (2022). ''Ev işleri üzerindeki payidar virüs.'' (Fiscaoeconomia,Volume 6, Issue 1, 81-98)

Creating Curiosity

I ended my previous performance by saying that I would tell Asude’s mother’s story in our next meeting. As Sevda Şener mentioned in her book "Audience Interaction in Traditional Turkish Theater," meddah created curiosity to ensure that the audience would return for their next performances. They did this by breaking their stories into parts and leaving them open-ended.

I used this method as a writing strategy. From what I saw, I succeeded in creating curiosity because my colleagues who watched the previous performance said they wanted to come to this one as well—and they did.

Feminist Aspect in Writing

While writing Asude's mother's story, I focused on the real stories of women who are survivors of domestic abuse which we know is a very big problem in Turkey. I read and watched many interviews.

And I included quotes and lines from these interviews in the story. This was a writing strategy I used to bring back the stories of women who had been silenced and suffered domestic abuse for years. Through the performance, I aimed to confront the audience with this reality, encouraging them to think about it and discuss it. Just as Judith Butler states that telling the silenced, suppressed, and censored stories of women is an act of feminist resistance, I believe that sharing these real women's stories also supports the feminist aspect of my project.

Using Comedy

According to Asude’s story, this was a more intense and heavy topic because it told the story of a woman who had been raped for years by her biological father. While telling such a difficult story, I asked myself:

How much distance should I keep from the emotions of the story?

How deeply should I draw the audience into this heavy subject?

How could I balance this weight?

First, I decided to balance the heaviness of the story with music and a lighter narrative style. Just as Brecht and Augusto Boal argued, my goal was not to overwhelm the audience with emotions to the point where they couldn’t think, but rather to make them reflect on the issue, remember that these real stories exist, and recognize that such stories are actually a societal problem.

After the performance, I even held a discussion with some audience members about the storytelling approach and how such a heavy topic should be conveyed. And for the next performances, according to my insights, and as Cevdet Kudret and Metin And also mentioned, just like the meddah did, I decided to work on comedy aspect of my storytelling to be able to balance the heaviness of the subjects.

That experiment helped me understand the importance of comedy in meddah performance.

Participation

Finally, in the second song, as soon as the classic Turkish music piece began—where Asude's mother, Meryem, expressed that she couldn’t tell anyone her sorrow and could only cry—the audience started singing along with me.

This was an unexpected and unplanned participation. In response, I spontaneously said, "Let’s all sing together, let it reach Meryem’s soul." As we know by now, improvisation is a part of the Meddah performance. So that helped me experience this improvisation aspect as a meddah. From that moment on, it really felt like we were singing for Meryem.

I believe that the ease with which the audience joined in was due to several factors: the way I positioned myself, the spontaneity of the performance, the conversational atmosphere that made people feel comfortable, and the fact that they were watching the performance for the second time, which made them feel it was okay to participate.

This became an important feedback moment for me, reinforcing the element of co-creation and participation that I aimed to establish in my performance.

These feedbacks were generally about acting, the story, the performance, and the music. After the performance, I also received comments in these areas during our conversations. For my next performance, I will try a different method of collecting feedback to trigger audience to reflect on the idea of female meddah, women’s issues, gender and the emotions and thoughts that arise in the audience regarding these topics.

Literature:

Aksoy. B. (2010), ''Conversations on Ottoman/Turkish Music''

And. M. (1993), ''Arts and Entertainment in Ottoman Culture''

Beşiroğlu. B. (2017), ''Gender and Women Musicians in Ottoman/Turkish Music''

After my fifth experiment, I took into account the feedback from my classmates and my own insights, and I performed the same piece again in Turkey for my colleagues, adding one more song at the end.

Even though the venue was a theater building, I chose to perform not on a traditional stage but in the theater cafeteria.When we consider the theater cafeteria in the context of Habermas's concept of the public sphere, a theater cafeteria can become part of the public sphere because it is a place where people discuss art, politics, and social issues before or after a play. For this reason, even though there is a conventional stage in the theater building, I chose to perform in the cafeteria instead of on the stage.

That day, my colleagues who had a show on the main stage were present. I told them that I was researching female meddah performances and that, if they were interested, I would like to perform my 10-minute piece for them and have a discussion afterward. Around 10 people responded positively, and after the main performance in the theater, I presented my piece in the cafeteria.

Participation

I asked Süleyman Abi, the cafeteria worker who served us food and drinks, if he could participate in my performance. In the script, a male character interrupts my singing by saying, “What kind of voice is that? Are you a man or a woman?” (This line comes from a scene where Asude, a woman disguised as a man, sings in a traditional coffeehouse, and one of the customers reacts this way.)

I included this participation element to break the classic division between audience and performer. Süleyman Abi, originally an audience member, became a participant in the performance, contributing to the creative process. This made the performance more engaging and surprising for the audience.

As Boal suggests, I wanted to move the audience away from passive spectatorship and actively involve them in the performance and creation process. By doing so, I was able to create a shared space between the performer and the audience, making the topic more real and instinctively engaging for them.

Character Clarity & Performance Approach

Feedback from my previous experiment suggested that I should make character distinctions clearer. To emphasize the character of Asude, a woman disguised as a man in the 1930s, I used a hat and a coat from that era, helping to establish a visual separation between myself as the narrator and Asude.

As in my previous performances, I started by explaining how I began researching female meddah storytelling, creating a casual and conversational atmosphere. However, unlike the traditional meddah style, where the performer has a more dominant role, I chose a softer and more inclusive transition into the performance—positioning myself as equal to the other people in the room.

Spatial Arrengement as a Feminist Narrative Form

I prepared the space for the performance by setting up a long table with chairs around it. The venue owner had assumed that I would set up a stage and perform there, so they had placed the table and chairs at the back of the space. However, this would have created a sharp hierarchy between me and the audience. Even though this setup was expected, I chose to break this hierarchy by placing myself and the musician around the table, at the same level as the audience.

As you can see at the beginning of the video, this equal seating arrangement made the audience feel like they were part of a conversation, allowing them to participate freely. As Boal also discusses in ''Theatre of the Opressed'' it helped transform the audience from passive listeners into active spectators/participants.