Works Cited

-

Liu, Kuili. The Origins of Nuo Culture. Beijing: Cultural Heritage Press, 2005.

- 刘魁立. 《傩文化探源》. 北京: 文化遗产出版社, 2005.

-

Jiangxi Cultural Gazetteer. Jiangxi Provincial Press, 1995.

- 《江西文化志》. 江西省出版社, 1995.

-

Pan, Naiyu. The Transformation of Family and Gender Relations in China. Shanghai People’s Press, 1993.

- 潘乃谷. 《中国家庭与性别关系的变迁》. 上海: 上海人民出版社, 1993.

-

Barthes, Roland. Elements of Semiology. Translated by Annette Lavers and Colin Smith, Hill and Wang, 1967.

-

Beauvoir, Simone de. The Second Sex. Translated by H. M. Parshley, Vintage Books, 1989.

-

Tian, Suqin. The Modern Inheritance of Nuo Opera and Gender Roles. Henan University Press, 2010.

- 田素琴. 《傩戏的现代传承与性别角色变化》. 河南大学出版社, 2010.

-

Yang Yunxia. Mask Making and Inheritance in Songtao Nuo Opera.

- 杨云霞. 《松桃傩戏面具制作与传承》.

- 中国傩戏网 傩戏法事_中国傩戏网

- 杨云霞 沿河傩面具雕刻工艺省级传承人 土家傩堂戏面具雕刻师_傩戏人物_中国傩戏网

- 贵州仡佬族非遗《傩戏》文化,竟然历几十代人传承_视频_中国傩戏网

3.1 Inspiration and Semiotic Interpretation

Drawing from Nuo opera’s symbolic traditions, my costume designs reimagine its gendered elements. Masks in my work deliberately lack defined facial features, emphasizing individuality over imposed gender identities. Materials like chiffon and metal are juxtaposed to symbolize both the constraints of traditional norms and the fluidity of modern gender expressions.

As Barthes asserts, “The significance of symbols lies not only in their form but also in the new interpretations they invite within cultural contexts” (Barthes 56). By redefining traditional Nuo symbols, my designs challenge entrenched narratives and invite viewers to question gender norms.

2.1 Mechanisms of Exclusion

Gender taboos in Nuo opera are deeply embedded not only in religious doctrines but also in patriarchal family structures. Pan Naiyu argues in The Transformation of Family and Gender Relations in China that “family systems use religious rituals to exclude women from public power, thereby preserving male dominance” (Pan 23). In Jiangxi, Nuo opera often aligns with village rituals led by male elders, where women are relegated to peripheral roles. This reflects the transition from matrilineal to patrilineal societal structures, perpetuating women’s marginalization over millennia.

1.1 Religious Functions and Gender Roles

The origins of Nuo opera can be traced back to ancient shamanic practices, where "masculine energy" was believed to drive out evil forces. As Liu Kuili notes in The Origins of Nuo Culture, “Nuo rituals emphasize 'masculinity expelling evil(阳,阳刚驱邪),' with women, seen as symbols of 'yin 阴,' excluded due to concerns over ritual purity” (Liu 68). Masculinity, associated with the sun and vitality, contrasts with femininity, often linked to softness or darkness, reflecting rigid gender divisions deeply entrenched in traditional Chinese culture.

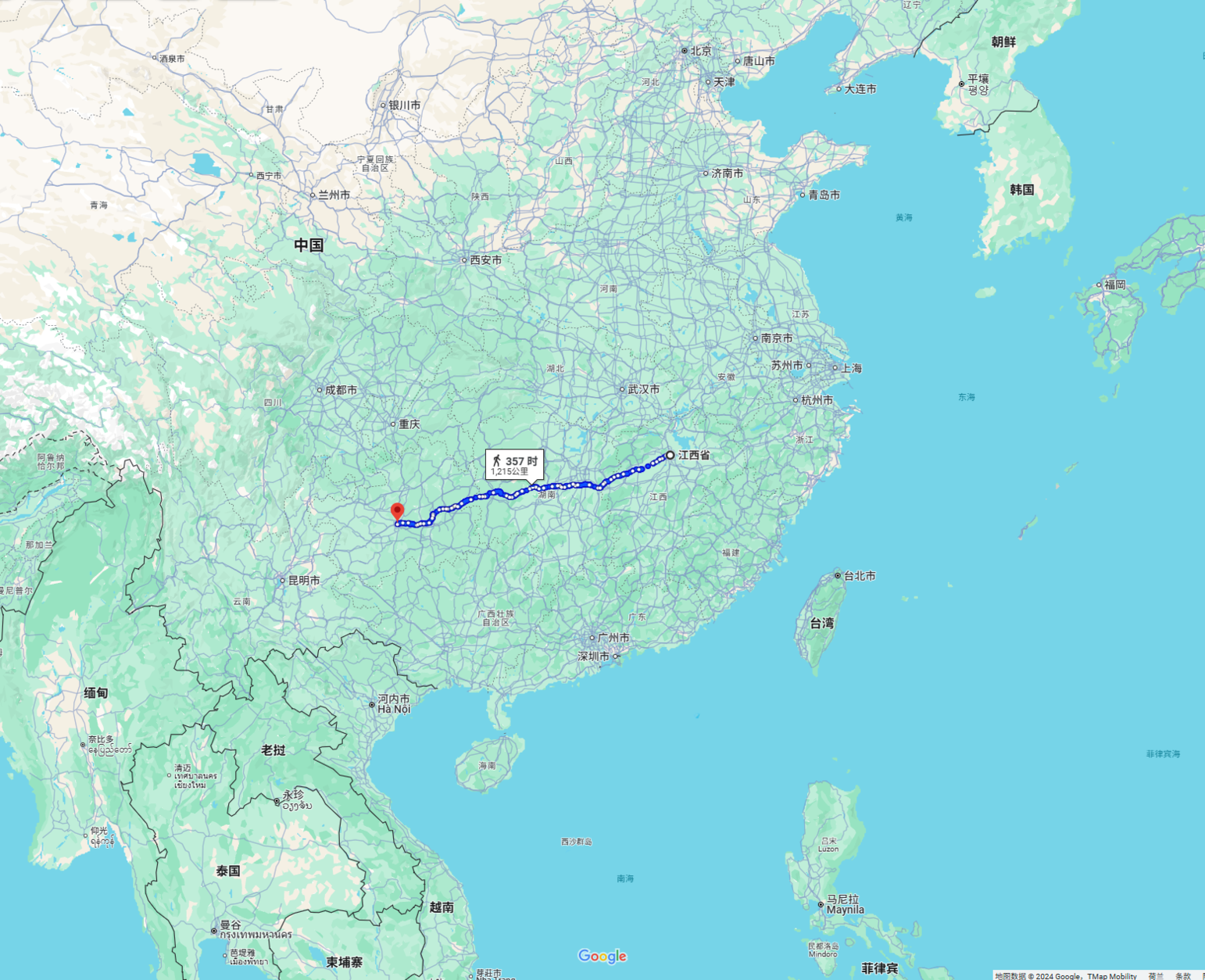

In Jiangxi, religious rituals in traditional Nuo opera emphasize purity. Primary masks for roles such as exorcists are worn exclusively by men, while women—even as spectators—are forbidden from approaching the ritual center, particularly during the expulsion of evil spirits. This exclusion underscores the belief that "yang energy" clashes with the "yin energy" of women (Jiangxi Cultural Gazetteer 112). By contrast, in Guizhou’s Songtao region, women are permitted to participate in certain secular Nuo performances, reflecting remnants of matriarchal traditions and the region's higher degree of gender inclusivity. These contrasting practices demonstrate how geographic and societal differences influence gender taboos.

2.2 Shifting Dynamics in Guizhou

Guizhou’s Nuo traditions, however, show signs of change. In certain secular performances, women have begun to take on roles as performers and even mask artisans. For instance, Yang Yunxia 杨云霞, a female mask carver from Songtao, has ventured into performance, challenging longstanding norms. Although women have yet to gain full acceptance in Nuo’s religious rituals, this shift marks a subtle yet significant challenge to traditional gender taboos.

The gender taboos in Nuo opera reflect deep-rooted power structures in Chinese culture. While Jiangxi’s practices highlight exclusion, Guizhou’s evolving traditions hint at potential change. Through costume design, these symbols can be reinterpreted, transforming exclusion into inclusivity and offering a platform for gender equity in cultural storytelling.

1.2 Gender Symbolism and Power Representation

The artistic elements of Nuo opera also reinforce gender stereotypes. Masks for male characters often feature bold, exaggerated designs—thick lines, heavy materials, and dominant colors like red and black—to symbolize strength and authority. Conversely, masks for female characters are softer, with delicate lines, light materials, and subdued colors, relegating them to secondary, often ornamental roles.

Roland Barthes’ semiotic theory posits that "symbols not only convey meaning but shape social perception" (Barthes 45). For example, the "General 将军" mask in Jiangxi’s Nuo opera, with its vivid red and black tones, symbolizes power and command. In contrast, the "Fairy 仙女" mask, adorned in white and gold, embodies purity and subservience, reinforcing gender inequality through artistic representation.

Male actors' cross-dressing to portray female characters further reflects the control of feminine symbolism by men. In Jiangxi, male performers playing female roles, such as the "Huadan" in Peking opera, distort femininity through exaggerated portrayals. This phenomenon aligns with Simone de Beauvoir’s assertion in The Second Sex: “Women have never been the subject; they are always the 'other,' defined within a male-dominated cultural framework” (Beauvoir 67). Such portrayals perpetuate patriarchal narratives, reducing women to supporting roles in cultural storytelling.

3.2 Costume as Cultural Critique

Costume design serves as both an artistic medium and a form of cultural intervention. Tian Suqin notes that “women’s engagement with traditional culture represents a deconstruction and reconstruction of gender taboos” (Tian 89). My designs incorporate metaphors such as chains and knots to critique gender constraints while envisioning liberation and equality. These visual elements challenge traditional power dynamics, offering new possibilities for cultural narratives.

Nuo opera 傩戏, one of the oldest theatrical forms in Chinese civilization, is deeply rooted in ritualistic performances where actors don wooden masks representing local deities or heroic figures. These "expelling darkness" and "praying for blessings" rituals encapsulate ancient hopes for a prosperous future—warding off evil, preventing disease, and seeking health and peace 驱邪逐疫,祁福安康. As a profound cultural symbol, Nuo opera embodies the historical legacy and spiritual aspirations of early civilizations.

However, as one of the earliest forms of Chinese theater, Nuo opera is fraught with persistent gender taboos. Women have long been excluded from participating in its sacred rituals, and male actors often cross-dress to portray female characters. These practices highlight gender inequality embedded in traditional culture, where such taboos act as both religious norms and mechanisms of social power reproduction.

Inspired by my recent work creating historical costumes based on Nuo opera, this paper explores the phenomenon of gender inequality within the art form. By tracing its cultural origins, I analyze how gender taboos reflect societal power structures and their representation in performing arts. Focusing on the cultural influences of Jiangxi and Guizhou—regions central to Nuo opera’s heritage—I delve into how visual language can deconstruct traditional gender inequalities and propose new possibilities for expressing female subjectivity within cultural narratives.