Relations 5 – activating and changing

Reflecting on new materialist thinking about all matter being vibrant and in motion (Bennet 2010), we should learn to think of built architecture as an ever changing process instead of an unchanging object, frozen in time and space. Change is inevitable due to temperature, humidity, microbial activity and interaction with different human and non-human beings, among other factors. When architecture aims at stability, change is seen as a failure – rendering architecture 'out of date' quickly after completion.

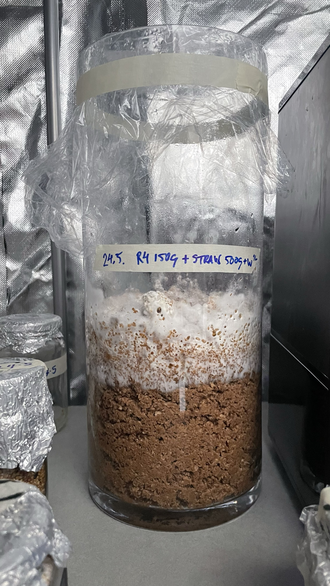

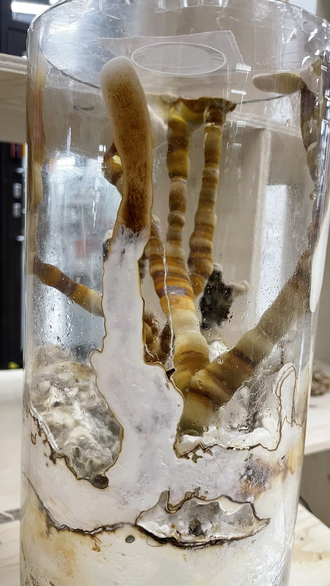

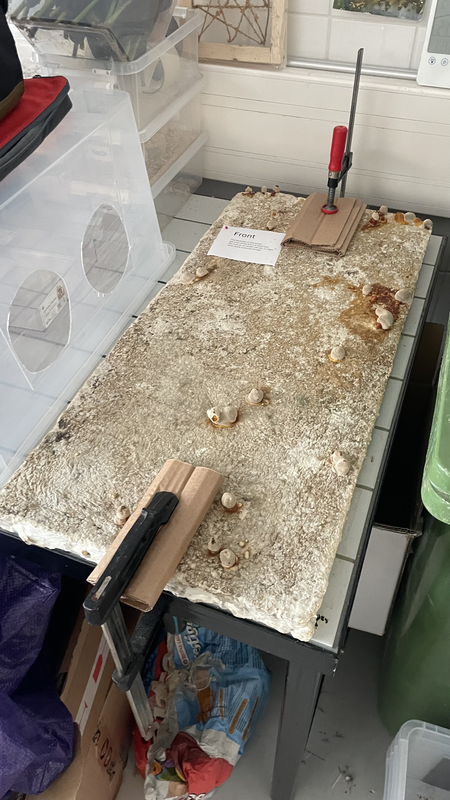

The physical embodiment Kudos – Library for Material Relations is designed to be in constant process of evolution. The making of it did not end the first time it was erected in September 2024. The design process remained in motion until and beyond the moment of installation. The success and appearance of most of the panels and objects wasn't certain until the last minute. The library of fungal explorations kept growing throughout the duration of the exhibition both in number as the panels and objects appeared from the grow tent, and concretely. As the fungi were not heatshocked to death but dried to hibernation, some of them continued growing, some grew fruiting bodies, some changed colour, and some of them reacted to the touch of the visitors. A reishi fungus (Fig. 23) (whether the singular form can be used when referring to fungi, is another discussion) kept growing, eating straw in its glass jar, reminding visitors of the vitality of fungi in suitable conditions, even making an attempt to escape once, reminding us of their life force. Clay elements appeared. People came and went, leaving some of their microbial companions in the space and picking up new ones from it.

During the month Kudos – Library for Material Relations was displayed, two discussions and two workshops were organized as part of the transformative apparatus. Both promoted change on the level of attitudes and ideas, the discussions through academic thought and the workshops on the level of bodily learning. All the events were open to the public and promoted through the information channels of the Designs for a Cooler Planet exhibition. However, the promotion wasn't very succesful and participation was minimal, mainly consisting of students, faculty, visitors and alumni of the university.

In the two discussions "What can we learn from fungi?" and "Designing with the more-than-human" the themes embodied in the project were deepened, small communities were formed and the space was activated. Two clay building workshops were organized in collaboration with clay artisan Mari Hermaja. Different clay building techniques were introduced, participants got to try them out and elements for the physical structure were created together. Through clay, aspects of the sensory experience of making and physical collaboration of humans and material were brought to the process as well as aspects of different temporalities. It takes aeons for clay to form and minutes for people to reform it. In buildings, raw clay can be worked on with bare hands, it can be easily repaired and reused endlessly.

As mentioned, there were only a handful of participants in the workshops, so no broad conclusions can be drawn. However, there was one participant who came to all the events. She was quite doubtful and full of questions. During the clay workshops, she complained she had never been good with her hands and she found her creation ugly. While mixing a light clay mixture with her feet, she continued explaining how uncomfortable and physically demanding she found the physical labour which led me to ask why she kept coming to the events. She replied she didn't know exactly but it felt important and that somehow her body guided her; that these events had made her realize she should value her body more and not only the brain. She, thus, activated the transformative potential of Kudos – Library for Material Relations.

Kudos – Library for Material Relations can change shape in different locations. At the end of the Designs for a Cooler Planet exhibition, the plywood frame was stored in cargo boxes to wait for new appearances. The frame will travel and welcome new libraries of local material relations in each locality. The library conveys stories of the local environment, of socio-material relations and collaborations. Library-goers can check out attitudes, worldviews, material practices, information, sensory experiences or microbial connections. The spatio-material experience of visitors will be analysed in further research.

After the project, the materials will not disappear but will instead change shape. Clay elements can return to the ground, slowly melting and changing shape from their rectangular form to organic formations, providing nutrients for different lifeforms through the organic fibres incorporated into them. Plywood structures can be repurposed further and finally decomposed. Fungal panels will be revived and assembled into a landscaping project on campus, where they may accelerate the decomposing process of felled trees thus regenerating natural processes held back by humans.

Commonly a process of architectural making would begin with the client's wishes, and a phase of sketching and hylomorphic design ideas would lead the way. In Kudos – Library of Material Relations we questioned this approach and included material gathering in the creative practice, an intimate material approach, enabled by the condensing of the project temporally and spacially. The posthuman feminist concepts of care and interconnectivity translated into the following practical material strategies:

1. Sourcing extremely local materials minimizes harm related to transportation and global supply chains both to the environment and humans, and enables building relations between people and their immediate surroundings.

2. Sourcing materials causing no harm and/or having a regenerative effect on the environment either through their removal and later return with regenerative capacities or through recycling if already in human use.

3. Growing materials ourselves (described in Relations 2).

4. Working with materials that can provide positive bodily affects or relations with people participating in the making and/or visiting Kudos – Library for Material Relations

These are not new inventions but rather a reintroduction of age-old practices. Frugal and caring material practices are built into many indigenous cultures (e.g. Kimmerer 2020). The remnants of a more relational use of materials can also be seen in the countryside of Finland, where the remains of old houses, built with local wood, clay and stone are returning to the environment, causing no harm but providing nutrients to fungi, insects and plants instead. Currently, however, the mainstream building industry is operating on a vicious cycle of extracting natural resources carelessly, creating building products that do not last long or age well, and cannot be returned to the natural cycles either.

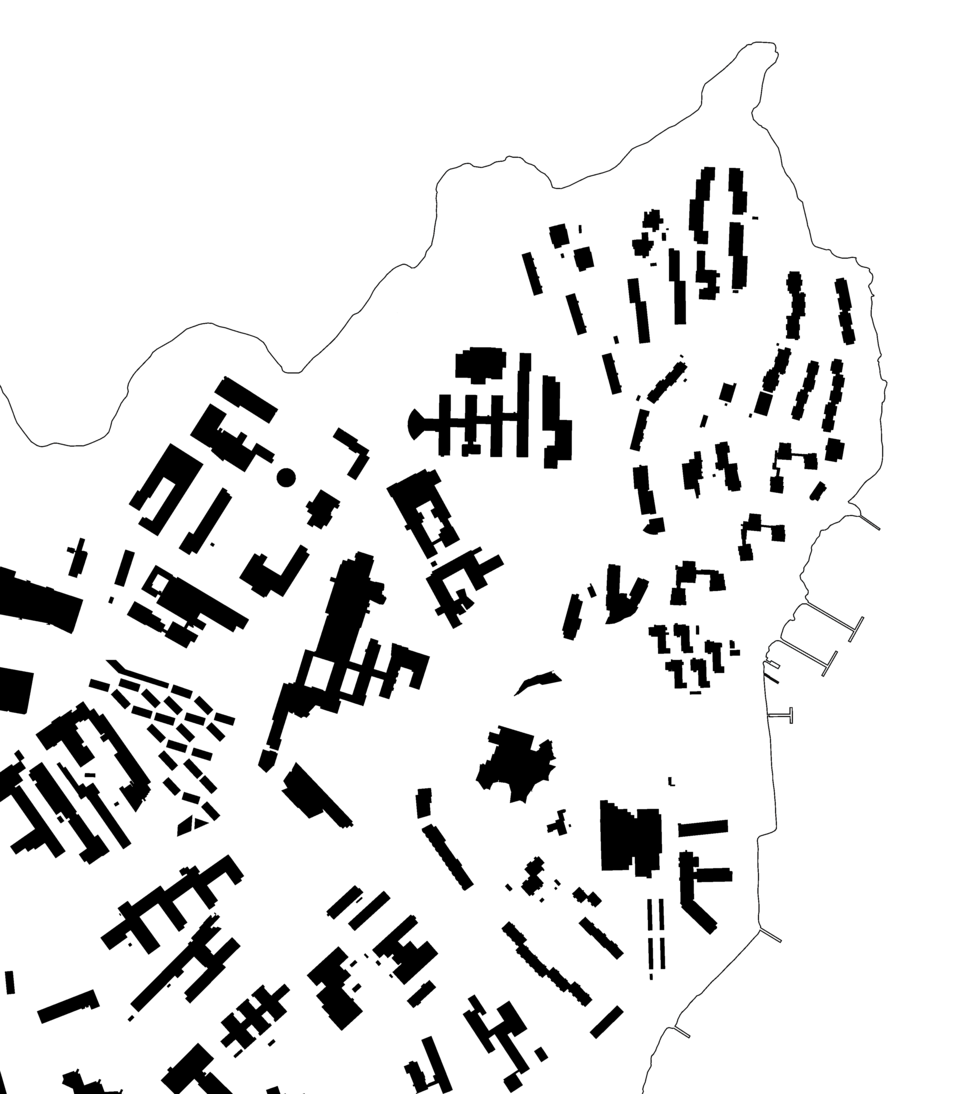

Because Kudos – Library of Material Relations took place at the Aalto University campus (Figure 4), materials were also to be sourced there to achieve an extreme degree of locality. The combination of human and non-human environments on campus led us into a material selection of common reed, clay, and recycled plywood (and communally shared fungal spawn, see Relations 2). The process of local material gathering provided me with a deeper understanding of material relations than when purchasing materials from a provider.

When gathering and transporting the materials oneself, it is impossible to overlook the effects these processes have on the environment (and on the individual), and the energy they require. In case of the common reed for example, I felt the joy in discovering it, I felt in my body the hardships of cutting the reed (and my hand in the process), sinking into the sticky mud of the shoreline and transporting the reed by bicycle (electric bike, but a bike nonetheless) to the workshop to minimize use of fossil fuels. I also formed a deeper connection to the material's place of origin, its conditions and inhabitants. I also needed to consider the suitable time for collection (between the last snow melting and the beginning of birds nesting season). As a result, I begun paying closer attention to the birds and grew attached to two swans living in the area. I saw them each day building their nest on a rock in early spring, the spring floods washing the nest away, seeing them on the bay when winter was creeping in, wondering whether they were going to migrate and feeling anxious about not knowing whether they had when they weren't there one day. At the moment (January 2025) I am expecting their return. (based on notes from my journal) (See figure 5&6)

Clay suitable for construction was found and sourced from the building site of Alusta pavilion (see Suomi & Mäkelä 2024), which was being built on the campus at the time. Clay ties us to the soil and place, it carries long cultural ties as well as strong sensory potentials.

As it became evident that a supportive structure for the more experimental material explorations was to be built for aesthetic, structural and functional support (see Relations 2), the hunt for recycled wood began. Instead of muddy boots, this material gathering practice required relentless emailing and telephoning. Eventually recycled plywood, on its way to waste, was found at a construction site on campus. Tire marks, stains and dents remind visitors to Kudos – Library for Material Relations of the material's previous use. The dimensions of the structure were designed based on the aim of zero waste. The scraps were collected and fed to the fungi. Unexpected relations were formed during this process as well, as I discovered generous amounts of materials on their way to waste and added to the project an operation of distributing them to several other designers and researchers to salvage them. In addition to plywood, smaller amounts of wood chips from the university wood workshops and cardboard from the offices and retailers were sourced.

Fig. 23: A live reishi growth took part in the exhibition. Having eaten most of the provided straw, it begun growing fruiting bodies towards the filter providing it oxygen, at the end of the exhibition nearly escaping through a microscopic gap -symbolising the strength of fungi. Photos by Elina Koivisto.

Fig. 26: Interchange of human visitors and the material space. On the left a child interacting with the material samples provided for the purpose. On the right a stool by Harvey Shaw, reishi and curly birch slowly turning orange due to the touch of exhibition goers. Photos by Elina Koivisto.

Fig. 24: Elements with clay and natural fibres being made by workshop participants on 17.9.2024. Photo by Elina Koivisto.

Fig 25: Elina Koivisto and mycologist Sari Timonen discussing "What can we learn from fungi?" on 9.9.2024. Photo by Maiju Suomi.

Fig. 4: Otaniemi campus map

with material relations

1 Common reed

2 Clay

3 Plywood

4 Woodchips, sawdust, cardboard

5 Space 21 fungal workspace

6 Designs for a Cooler Planet exhibition

By Elina Koivisto

Fig. 5 Gathering materials herself, architect-researcher Elina Koivisto felt the weight of material choices in architecture in her body. Local common reed collected into a recycled container by hand, swans in the background, transported by electric bicycle. Photos by Elina Koivisto.

Fig. 7: Material practice of searching materials for reuse created human and temporal relations to the previous owners and locations as well as others in need of materials. Me organizing transportation for materials at the construction site. Photo by Elina Koivisto.

Fig. 6 The material gathering practice created relations between myself and a swan couple. They observed me cutting reed, I have observed them ever since. Photos by Elina Koivisto.

Relations 4 – exploring and creating

Another summer school was organized in August 2024. Participants of the summer school were architecture students (including landscape and interior architecture) from Aalto University. The seven participants of the summer school were invited to learn and engage with fungal mycelium, design and make elements for the physical embodiment of Kudos – Library for Material Relations and reflect on their experience through their learning diaries. Exercises for experiencing different stages of creating with fungi were planned.

"During the workshop we will learn to understand fungi as living beings, we will learn how to grow them and how to mould them. Each participant will ideate and create mycelium building elements that will be exhibited at the Designs for a Cooler Planet exhibition in September as part of Kudos – library of material relations." (from the email I sent to the mailing list of the Department of Architecture 31.5.24)

With the children I clearly had to retain a leadership position and control the learning situation to prevent it from getting out of hand (at one point nitrile gloves as water balloons were thrown). With the students a more equal community of practice (Lave & Wenger 1991) was formed. Doina Petrescu discusses how "in participative approaches, the architect should accept losing control. Rather than being a master, the architect should understand himself/herself as one of the participants" (Petrescu 2005). As I had only explored working with fungi for less than year, I couldn't have taken the role of an expert even if I wanted to and this truly turned into a process of co-speculating and co-creating.

“The atmosphere in the workshop was charged with creativity and curiosity. We were all stepping into the unknown together, experimenting with something that had no guaranteed outcomes. This shared sense of exploration made me feel more confident about my own contributions and excited to see how our experiments would turn out." (From the learning diary of student 1)

Beginning the course with a visit to a nearby forest set the tone for understanding that we would be working with unpredictable, living beings, the likes of which are everywhere in and around us doing their invisible care work. Student's observations led to lively discussion on capitalism, biomaterials and relations among others.

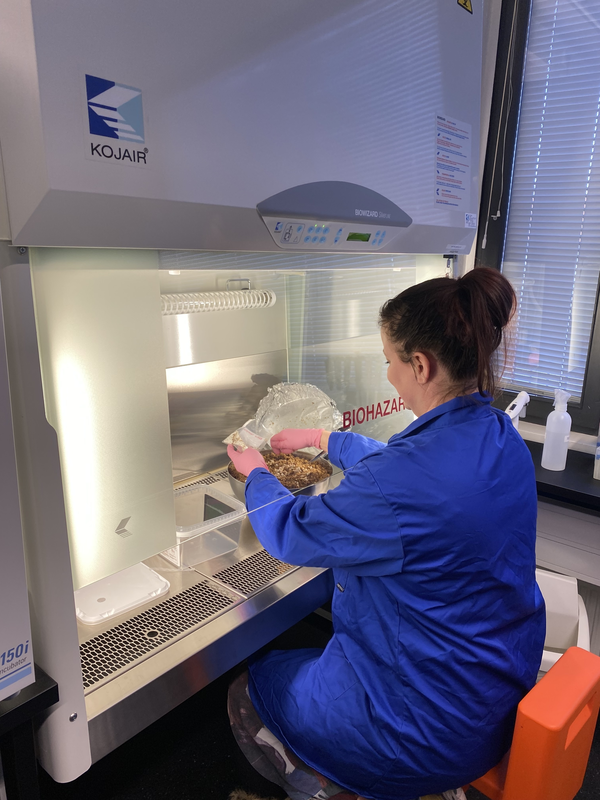

After some theory, tools and the workshop space had been introduced, it was time to dive directly into experimenting to reach the full potential of bodily knowledge in the learning process. The first exercise was to gather some organic material to use as a substrate for the fungi. The diversity of materials was delightful as the students came in with fallen leaves, tree bark, garlic peels, thistles, flowers, linen cloth and more. We practiced using the still air boxes (SEB), sterilizing substrates with boiling water and inoculating it with the live spawn prepared by me. Even though we worked on a campus where state of the art laboratories and equipment are available, I wanted to promote low-tech, approachable techniques for their empowering qualities. All of the experiments were successful despite the low-tech work methods and natural materials, which surprised us all.

The main task of the course was to design and create elements for Kudos – Library for Material Relations together with fungi. I had imagined brick or panel-like elements to fill the compartments in the structure but the students created fantastic ideas from a hat to a linen-fungi millefeuille block that I never would have been able to explore by myself in such a short amount of time. This process was co-speculation in action.

Once again the role of bodily knowledge and "knowing from the inside" (Ingold 2013) could be detected as several students experienced the theoretical information distributed on the first day as complicated and intimidating, but after testing, the process begun making sense. Some students experienced knowing through making quite clearly:

"As soon as I got my hands into the fungal substrate I understood better, how to work with it. The situation reminded me again about baking sourdough, where you inquire from the dough, through your haptic sense, what stage it is in, what it needs and what could be made with it. It is easy to understand when you have haptically familiarized yourself with the dough or fungal substrate but explaining it with words is very difficult. Maybe this is exactly what bodily knowledge is?" (From the learning diary of student 2, original in Finnish, translation by me)

The students also discovered what multisensory potentials working with fungi holds. I myself realized how much I had learned to rely on my sense of smell in assessing whether the fungi were well or unwell in the grow tent. The substrate test on garlic peels threw me off. Every time I opened the tent, it smelled odd and threw me off. I was also able to pass on this olfactory knowledge as one of the grow bags that the students begun to work with looked fine but smelled sour. The smell of fresh fungi, on the other hand, transported the students back to the forest:

“the earthy scent of the mixture transported me back to the forest, evoking a sense of calm and connection to nature - -” (From the learning diary of student 1)

The last task on the course was assembling the supporting structure of Kudos – Library for Material Relations together with the students. It was the first experience of 1:1 size construction for many of them, giving them the perspective of what construction is outside of their drawing boards. We also lifted some bricks for weights inside the structure which made some of the students realize it was the first time they held an actual brick, felt its weight and understood how much energy moving it requires, which led to a discussion on the use of fossil fuels in construction and how drastically our way of building would need to change if they weren't available anymore.

Again, the products of this co-creation resulted in unexpected results. Uninhibited experiments were made and the co-creative making surpassed my own imagination and skill. As to the question of knowledge in the body and in making, the data from the workshops reveal that personal interaction with the fungal mycelium was crucial in the learning process of the participants. They experienced a shift in their worldviews and their professional viewpoints.

(Reflections based on my journal and audio recordings unless stated otherwise)

Relations 2 - growing and caring

When pondering our material choices based on reciprocal care, increased agency and vibrant matter, fungal mycelium caught our attention. In Kudos – Library of Material Relations the role of fungi is both concrete and symbolic. They offer possibilities for new material working methods based on growing and caring instead of extraction, and opportunities to create with a being that has been traditionally categorized as a thing, rather than as an actor. They are profoundly feminist as they are the invisible care workers of nature, creating life and death, embodying interconnectivity and entanglement.

The interest in fungi has increased over the past years in several fields from biology to anthropology and from architecture to medicine. Biologist Merlin Sheldrake and anthropologist Michael J. Hathaway call them "worldmakers" and argue they have the potential to shape the future of both our planet and us in unrecognizable ways (Sheldrake 2020, Hathaway 2022) whereas anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing uses them as a symbol for our need to build new livable worlds for us and others living in the ruins of capitalism (Tsing 2015). For the architecture and design industry, the non-extractivist nature, the possibility to make with rather than make of, and finding uses for agricultural and industrial sidestreams, have all proved appealing. Some projects in this realm include Hi-Fy by The Living (Frearson 2014), MycoTree by Block & Hebel (Frearson 2017) and In Vivo - Living in Mycelium by Bento Architects & philosopher Vinciane Despret (Fakharany 2023), which the authors describe as "the historical starting point of this new era, called 'Mycelocene'."(Despret et al. 2023)

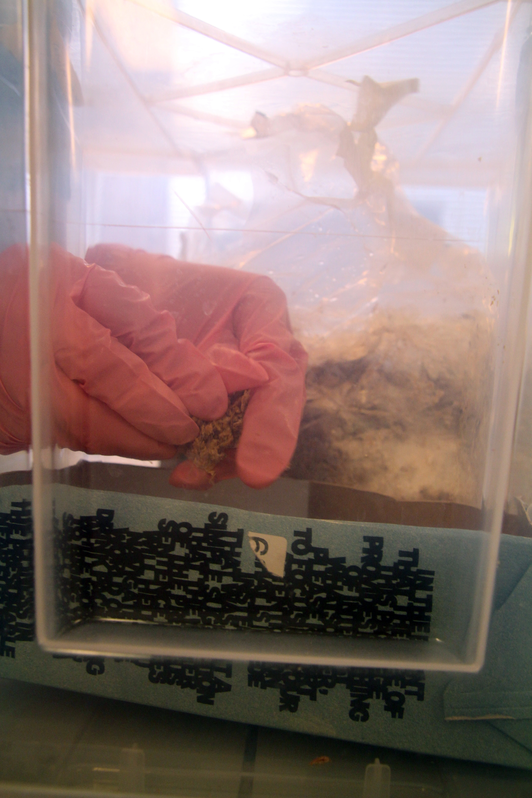

The live fungi helped us in our quest to rid ourselves of the habit of imposing our design ideas onto dead matter (see Bennett 2010). Instead we let the material beings guide us. A process of material tinkering and exploration began in January 2024 and continues to this day, taking different forms from semi-passive observing to relentless production. At first I hung onto my habitual ways of working. I bought a grow kit product for growing oyster mushroom (Pleurotus Ostreatus) from a commercial provider and placed it neatly on my office desk (Fig.8&9). I immediately felt a sense of responsibility and worry over my new companion, but I also felt anticipation and joy as thin white strands of hyphae begun to appear in the box.

After my first, timid experiment, I understood that I had to let go of my preconceptions about how an architect works and change my habits to accommodate the needs of the fungi and how to work with them. While I built suitable conditions for the fungi, their transformative potential began to reveal themselves to me as simultaneously a community of people and things started to form. Fungi are builders of networks and connections in the forest (Hathaway 2022) as well as human communities and alternative economies (Tsing 2015). Mycologists agreed to be interviewed, local fungal entrepreneurs and designers shared information and guidance, fungal spawn was distributed communally between researchers and experiences and experiments were shared. My neighbours collected glass jars and cardboard boxes and a local candy store donated plastic boxes. Fungal species joining the community were Ganoderma Lucidum (Reishi), Pleurotus ostreatus (Oyster mushroom) and Trametes Versicolor (Turkey tail mushroom).

This process of care and nurturing strengthened my sense of responsibility for all the living beings affected by the sourcing of any materials. After trying to fit them into my realm, I created suitable conditions for them, fed them, looked after them and made shapes with them, after which I dried them into hibernation instead of killing them by heat shock as is habitual (e.g. Alemu et al. 2022, Mycela Labs, Mycelia). Afterwards they will return to suitable conditions and they can continue their lives as active worldmakers, a plan deemed viable by a mycologist (Timonen 2024). I simultaneously felt the burden of care because I needed to balance my schedules between their wellbeing and the rest of my life. I felt guilty when I failed to provide them with approriate conditions, something I never felt when working with more common shop-bought building materials.

Maria Puig de la Bellacasa reminds us that: "Instead of focusing on the affective sides of care - - staying with the unsolved tensions and relations - - helps us to keep close to the ambivalent terrains of care." (Puig de la Bellacasa 2017) Fungi resist the romanticism that Picon blaims Ingold for (see Introduction) in making with materials. One cannot touch or caress or mould fungi as one does with clay for example, because sterility must be maintained to avoid contamination. However, my journal notes and the experiences of workshop participants (relations 3&4) demonstrate how caring relations can create a sense of intimacy nonetheless. Maria Puig de la Bellacasa reminds us that "Care is not about fusion; it can be about the right distance." (Bellacasa 2017) and Donna Haraway has written about "intimacy without proximity" (Haraway 2016).

"Clarity can be extremely dangerous. Clarity can have the stink of death about it, for it allows no compromise, no alternative visions, however indistinct and unsure." (Frichot 2019) A vital lesson for co-surviving and co-creating I learned from the fungi was tolerance for uncertainty and letting go of the illusion of autonomy and control that have led us to the mess we are in. Even though it was always the goal to let go of the designer ego and see where the open-ended process leads, it took some time to transfer from theory to bodily practice. In my journal, one can see exactly the moment when I gave up control and started to trust the process:

"I wonder if any of this is going to work. I can't breathe. I have a weight on my chest. A bit teary-eyed too."(My journal on June 26th, 2024, original in Finnish, translation by me)

"Today I realised that working with fungi is a perfect exercise for giving up control. Until now I have thought about it from an aesthetics point of view, but also this process is strongly out of my hands. No tool, that I have previously used to control the [design] process and keep schedules, is valid."(My journal on July 8th, 2024, original in Finnish, translation by me)

"The panels are growing by themselves in Otaniemi. I feel like laughing. It's somehow funny that while I am on vacation, the fungi do what they please. I don't feel anxious anymore, I feel tingly."

(My journal on July 18th, 2024, original in Finnish, translation by me)

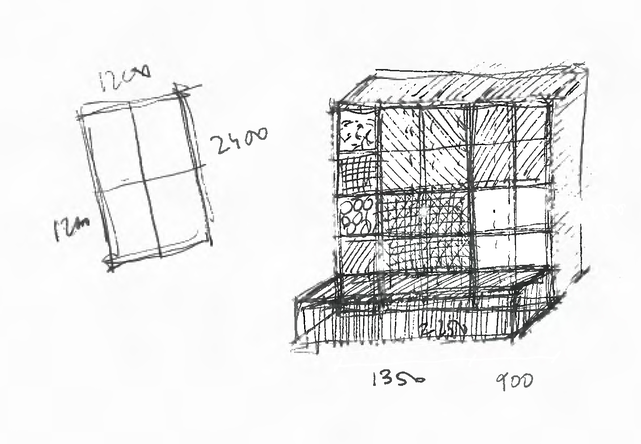

The conventional side of the design process took place in stages. Whenever we needed to provide the fungi or workshop participants with information, a decision on form or dimensions was made. The uncertainty described above informed the design process. The possibility of all the experiments failing loomed over us and unpredictable aesthetics was a given. Thus a supporting structure was decided upon for framing the experiments, to allow them to fail and take unintended forms but also to support the experience of those coming across fungal materials for the first time as some sense of familiarity and security is necessary to allow one to open oneself to new things. During the period of material tinkering we studied the aesthetics and forms the fungi would suggest. What we understood was that they are not interested in formgiving. They follow nutrients, moisture and oxygen into which ever shape you provide for them. Thus any shape one intends to co-create with fungi is eventually the creation of the human. However, what fungi seem to have creative potential for are textures. Thus we decided to play with textures instead and rely on conventional rectangular forms to, again, support the experience of visitors and to direct attention to the sensory and relational experience instead of 'fancy' forms.

Fig. 18: A student breaking mycelium grown into wood chips into a formwork made with milk cartons. Photo by Elina Koivisto.

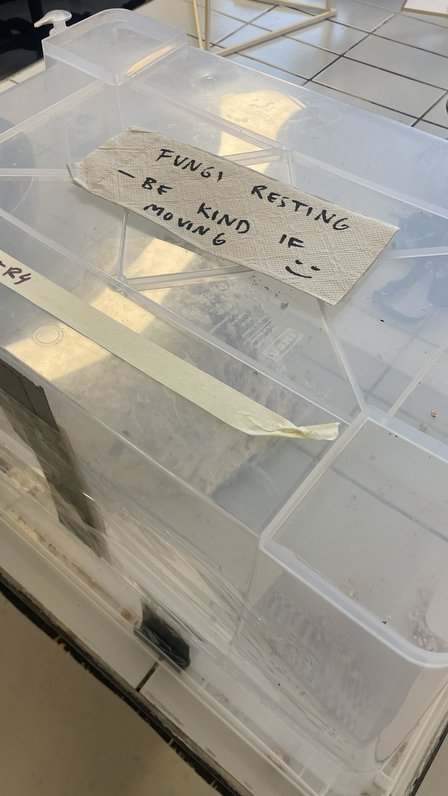

Fig. 20: A sign someone made in the workshop put on top of a drying fungal object showing the bonds forming between students and fungi. Photo by Elina Koivisto.

Fig. 16&17: Results of the first assignment. When asked to search for substrates from the area, Yulan Li brought fallen leaves and Sini Hinstala brought thistles. Reishi spawn grew well in both. Photos by Elina Koivisto.

Fig. 22: Examples of elements and objects created during the course.

Hat by Julia Töyrylä, reishi and ricepaper

Chessboard by Sini Hintsala, reishi, turkeytail and woodchip

Photoframes by Yulan Li, reed, reishi and woodchip

Block by Sara Kannasvuo, reishi, linen and woodchip

Photos by Elina Koivisto.

Fig. 19: Students reacting to seeing the creative work of fungi and themselves after a period of growth in the tent. Photo by Elina Koivisto.

Fig. 21: Fungal ikebana sitting among petridishes, glassjars and growbags of fungi growing. Photo by Elina Koivisto.

Phases in practical making with fungi:

1. Acquire fungal spawn and organic substrate.

2. Sterilize substrate and equipment.

3. Inoculate substrate with fungal spawn in sterile environment and let grow in a growbag in suitable conditions.

4. Design the shape and make a mould.

5. Move substrate colonized by mycelium from bag and break to mould in sterile environment and let grow in suitable conditions.

6. Remove mould and let grow some more.

7. Let dry in room temperature in a ventilated space.

8. Assemble.

Fig. 11 Sketches from design sessions of Elina Koivisto and Maiju Suomi. Top row in June and bottom row in August.

Program:

19.8.

Visit to a forest & Introductions

20.8.

Mycelium theory & workshop introduction

Assignment for gathering substrates

21.8.

Inoculating brought substrates & sketching

22.-23.8.

Visit to Alusta pavilion & sketching

Building moulds

26.-27.8.

Making elements with pre-grown substrate

28.8.

Assembly of Kudos frame

29.8.->

Unmoulding elements when fully colonized

Literary assignment:

Keep a diary throughout the course. Write at least 0,5xA4 per day. Draw. If you think better in movement, you can also make sound recordings.

Concentrate on your experience. Sensations, emotions, reactions. Smell, sound, touch, temperature, movement, the inexplicable. How did you expect to react and how did you react? How did you feel before a situation and how did you feel after? What made the change? Think of yourself as a human being and an architect. How do you feel as an architect? How does this experience change you as a designer, if it does?

Discuss your design and making process. Reflect on your design decisions and what you base them on. What did you decide to do? Why? How did it work out? Think about your design process before and now.

Practical assignment:

The design task on this course is to design and create an element or elements together with fungal mycelium to be exhibited in 1 or 2 rectangular spaces (size: W373xH373xD385).

The elements are exhibited as part of “Kudos – Library for Material Relations” spatial installation at the Designs for a Cooler Planet exhibition in Väre from September 5th to October 3rd. The elements in the exhibition will be credited to the students.

Each student will receive two grow bags of mycelium growing in recycled wood chips sourced from Väre wood workshops. One bag is reishi and one is turkey tail mushroom. They cannot be mixed in the growth phase but can be used in the same installation as separate elements.

Fig. 10 The story of the panel that made me let go of control from a jar of shared reishi spawn in a glass jar donated by a neighbour, through inoculation in sterile Biofilia laboratory and first growth in grow bags to spreading into a formwork, growing again in the warm and humid tent to finally drying in room temperature over my summer vacation growing fruiting bodies and creating a fascinating surface of textures and colours.

Lab photo by Harvey Shaw, others by Elina Koivisto.

Relations 3 - learning and failing

On the quest that Elke Krasny sent us on in the introduction, namely dethroning the autonomus architect, including different situated, bodily knowledges of participants is a necessity. Through "co-speculation" (Lohmann 2018) or "distributed thinking through making" (Vega 2024) with different people it is possible to access several approaches and experiences through a co-creative process. Participatory approaches in design and architecture are often understood as taking part in processes concerning oneself. Since Kudos – Library of Material Relations is a transformative act battling the global crises, I see all living beings, ultimately, as stakeholders. With this in mind, the project allows architectural practice to expand to its pedagogical dimension, following the ideals of feminist spatial practice.

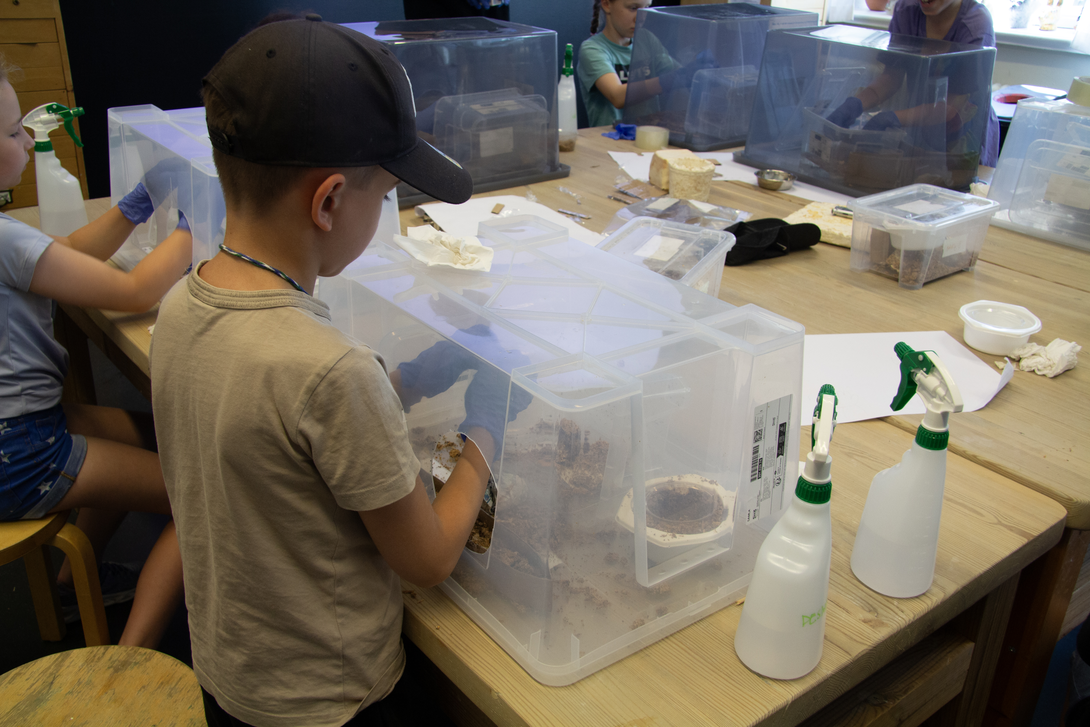

A week-long summer course for eight 10-12-year-old children called "Rihmasto" (mycelium in Finnish) was organized in June 2024 in collaboration with Annantalo cultural centre for children and youth in Helsinki. Annantalo organizes courses, exhibitions and events, which are open for all. The summer courses have a fee, but an exemption is available for low income families to enable participation for everyone. I had architecture student Cisil Havunto and design student Harvey Shaw assisting me. Staff from Annantalo were also involved.

Children were chosen as a group usually overlooked in decision-making processes but also for their lack of harmful preconceptions. Their open-mindedness became evident on several occasions during the course, when I asked the participants whether making with fungi sounded odd (transcription from 3.6.) or whether touching fungi felt strange when working (transcription from 4.6.) but they didn't see it as odd at all. Also, on the first day when asking them to draw or paint fungi, several of them drew imaginary settings where fungi were presented as actors. This led to a discussion about how fungi are commonly perceived as stationary, passive things, when in fact they are active beings with agency.

The practical aim of this course was using architecture and bodily making as a pedagogical tool for futures thinking, to co-create elements for Kudos – Library for Material Relations, and explore how children interact with the fungal mycelium, thus producing diffractive knowledge of making with fungi. A week-long program of creative activities and discussions was planned, prioritizing individual possibilities for learning and creating through bodily processes following feminist pedagogies. A learning environment with simple enough tasks and low-tech solutions was created to support the learning of everyone regardless of background and skill level.

A field trip to Aalto University familiarized the children with the university facilities, broadening their vision of their own future possibilities and those of the society in general. In Biofilia laboratory they learned about the transcorporeality of their own bodies through exercises of seeing the bacterial growth transferred from their fingers on a petri dish, and the microbial life of their saliva on a microscope. In Space21, where Harvey and I both work, the children got to experience mycelium objects with all senses, some fresh from the grow tent and some already dried. All of the children reacted to the strong fungal smell of fresh mycelium.

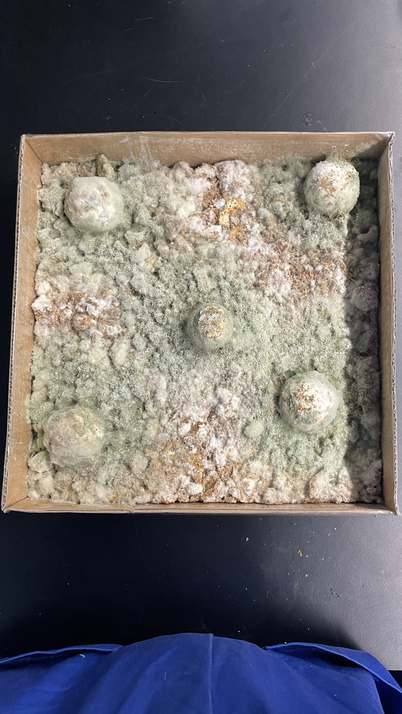

Three excercises included working with fungi. On the first day everyone received a starter box for home-growing oyster mushrooms. Three of the children immediately formed caring relations with their fungal boxes and named them. On the second day, objects for taking home after the course were made. The children wanted to make, for example, swords, axes and stars. After warning them of the complexity and possibilities for failure, we helped them finish the task. The last fungal exercise concerned the panels intended for the Kudos – Library for Material Relations. Square formworks had been prepared for them to decorate and fill with pre-grown mycelium-straw-composite. They found paper maché balls in the classroom which weren't meant for the task. Again, I explained the risk for contamination and considered forbidding them for the sake of successful execution of the physical structure but decided against it to support their creative processes and respect their freedom of choice instead. Even after serious contamination issues, I stand behind my choice. I see ensuring their true agency in the process important; to avoid using them for my own purposes. Doina Petrescu, for example, has warned against exerting control through participatory processes (Petrescu 2005).

For a week after the course I fought a desperate battle against contamination in many of the swords, axes and panels, salvaging some, losing most. First I grieved for the deformed panels and what I saw as the aesthetic failure of the Kudos – Library for Material Relations but soon the devastation of failing the children overcame it. When co-creating with vulnerable participants (humans or otherwise) the architect should be well aware of the power they hold over the participants and the responsibility they must carry should something go astray. One can not be too idealistic but truly consider the consequences of failure. However, the disappointment soon turned into an understanding that this is the trouble we have to stay with (Haraway 2016) if we are to overcome the exclusivity and disconnect of architecture. The design decision of having a stable frame for the experiments proved crucial.

"Only now did I realize what a responsibility this embodies. Beforehand I only considered the pride and joy the children would experience from seeing their elements as part of an architectural artefact, but I didn't consider at all what the consequences of failure would be!" (My journal 10.6.24, original in Finnish)

However, the interviews (7.6.24) revealed that the children were content with the week, they learned new things that they carry with them and they made new friends. Making friends seemed to be priority to them, which once again strengthened the notion of the importance of relations and community that can be built around a common subject. Architecture worked as a tool for social value making. One clear observation from the course was the importance of making as a tool for learning and knowledge (Ingold 2013). The children were quite restless through my speeches and all printed instructions were left crumpled on the floor, but when working with their own hands they transformed into a focused and excited group asking questions and concentrating on the task at hand. Even if the physical objects failed in practice, the knowledge embodied in the process remains.

(reflections based on my journal, audio recordings and interviews of children conducted on 7.6.)

Fig. 14: Blue moulds joined the creative community uninvited preventing oyster mushroom from growing and creating a panel intended for Kudos physical structure.

Photo by Elina Koivisto.

Fig. 12: Participant of the Rihmasto course exploring working with fungal mycelium, making a bowl for himself at Annantalo in June 2024. Photo by Elina Koivisto.

Fig. 13: Participant of the Rihmasto course familiarizing themself with a block of fungal mycelium through visual, olfactory and sensory means at Aalto University, Space 21 in June 2024. Photo by Elina Koivisto.

Program:

3.6.2024

Drawing of fungi/mushrooms as an icebreaker excercise

Starting of growth for home grow box of oyster mushroom

Pressing fingerprints on petridishes

4.6.2024

Making an object with pregrown mycelium for taking home

5.6.2024

A fieldtrip to Aalto University

6.6.2024

Making panels for Kudos – Library for Material Relations

7.6.2024

Arts and crafts, researcher interviews