Over the upcoming hours, this pseudo-touristic engagement with the city escalated. I lost my return airport ticket and, while looking for a place to reprint it, my friend lost her bag and wallet. For some hours, we felt that we were doomed. Fortunately, some money that remained in my bank account meant that my friend could purchase a return train ticket (to her home city in Italy), and a little improvised flirtation with a hotel receptionist helped me find a resource to reprint my ticket on time, and return to my (in-)secure home, broke and relieved.

This mix of anxiety and joy is embedded in these photos. If people tattoo their skin to mark tense situations, then the Venice-based photographs tattooed both joy and pain upon the holographic body of a digital selfhood. It is an exhibitionistic display of failure, in which holidays and daily life are simultaneously portrayed as modes of traumatic escapism. The dancing movement and the role-playing captured in the photograph stage an attempt to happily, if also melancholically, redefine the feeling of success. They beautify injuries of precarious living by sculpting ephemeral monuments of defeat that call for a different set of pleasures: the pleasure of circulating one’s image in urban and cyberspaces; the pleasure of creating creative forms leisure; and the pleasure of acting as an art object to be seen. Most importantly, the pleasure of living like a ‘person’ with some sort of control and impact — despite the lack of job, social status, and material comfort.

The next question that arose at this point was: how can this material be presented and understood as ‘art’? When it comes to presentation, there were several lines of direction. Ideally, all of these visuals would form the basis of a photo-textual exhibition — one that can be presented in a ‘proper’ gallery space and in the pages of a book. Both of these modes of exhibition, however, required funding and networking that was beyond the capacities of an hourly paid, semi-unemployed expat practitioner.

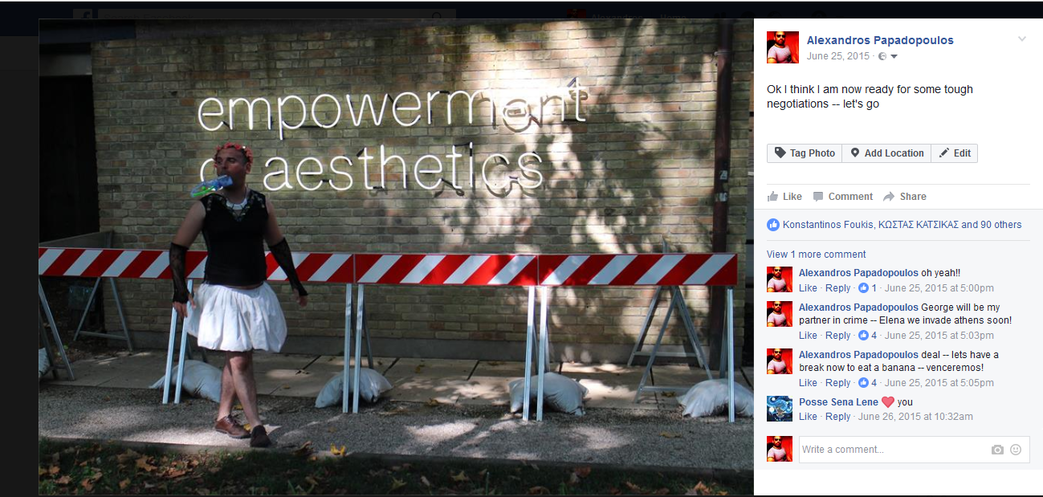

My initial response was to use the ideas, memories and visuals of this essay — orally and bodily — in a series of performance-lectures to be presented at academic conferences and art festivals. This presentation-project was entitled as How to Use Gay Nazis in Job Interview. In addition to provocative lectures, this same title encompasses all the digital, academic, and streetwise stories that reused the images of The Homonazi Effect into a new cycle of sensations across digital and urban spaces. In the performance-lecture, artistic demonstration took the form of striptease act. When I posed the question: ‘what can you do with this material? How can you exhibit it?’ I began to remove the clothes of my ‘professional’ academic panoply: the suit, the vest, the bow tie, and the shirt. I was finally left with a T-shirt printed with the exact same picture from Venice that I had posted on Facebook in August 2014. I then admitted that this T-shirt had only cost me £10.

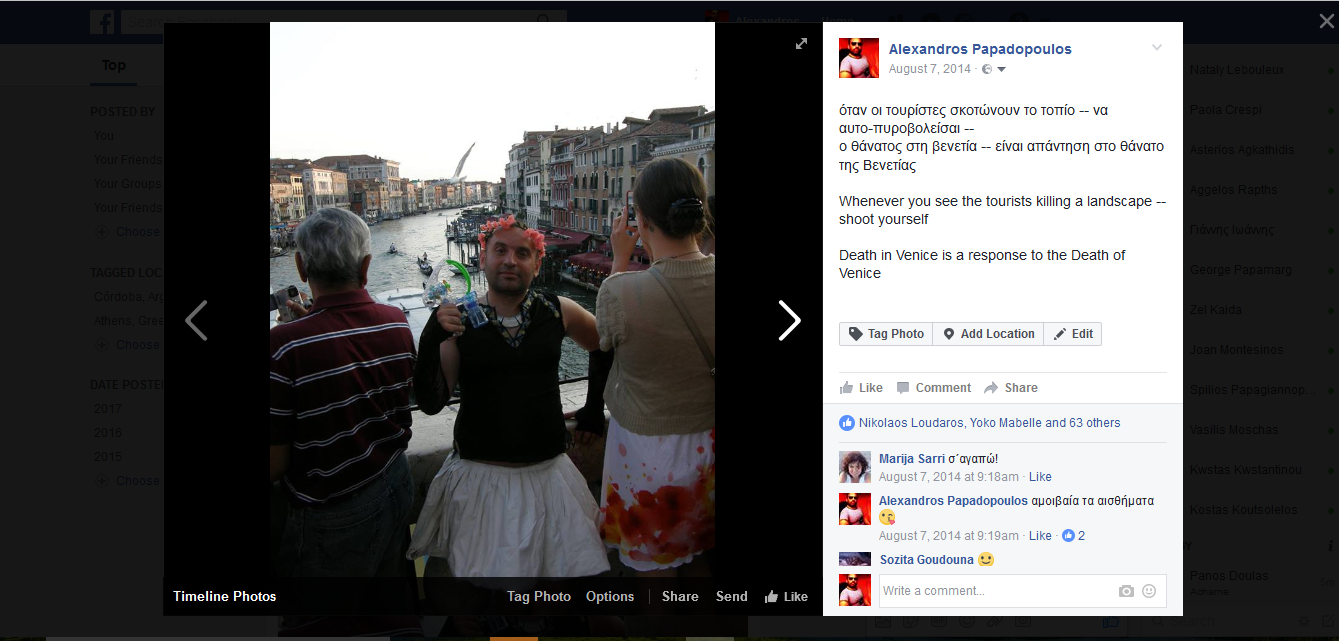

This picture was shot near the entrance of the 2014 Venice Architectural Biennale. It is a document of a bittersweet memoir. In the summer of 2014, I arrived almost penniless in Venice, accepting the invitation of friends who offered to pay for the airport tickets and hostel accommodation. I brought with me the costume I had used for the character of the gay Nazi, aiming to stage site-specific interventions. I hoped to both see and show how a new locality could transcend the semiotic power of this styling.

In The Homonazi Effect, I wore a costume featuring a tutu-like fustanella — the traditional folklore costume of national heroes, or the so-called tsoliades. This drag queen stylisation corresponded to the mix of ultra-right-wing nationalism and gay-porn-madness that coloured the persona of my interlocutor. In Venice, I replaced the pseudo-leather corset with a sleeveless shirt, and I started dancing to the music played by a bubble-making pistol opposite from the entrance of the Biennale [see figure 2]. Visitors started taking photographs of my activities, mistaking ‘my show’ for part of the exhibition. My body became a sightseeing architectural deceit, and this positioning continued when I strolled into the Biennale, adopting various postures and gestures in an attempt to playfully cross the line between exhibit and spectator [see figures 3, 4, 5].

This game extended beyond the space of the exhibition and invaded the city. Due its monumental character and architecture the whole city of Venice is seen as a museum, yet there was a large spectrum of opportunities for an art of ‘self-objectification’, one that allowed jumping from the position of a spectator to that of an object to be seen. Upon exiting the doors of the Biennale, I continued to wear the costume as I strolled the packed streets, competing with the sightseeing attractions for attention. This style of moving and posing allowed me to both mix with and differentiate myself from the crowd of tourists. The act of consuming a cityscape dissolved into an act of becoming a part of the cityscape. Echoing what Michel de Certeau might have a called a ‘tactic’, Walter Benjamin ‘flânerie’ and Situationists ‘derive’, this spatial movement bridged physical with digital pleasures of cruising. Photographs of my endeavors were posted online on my Facebook wall: being too broke to consume anything else in this city, the digital representation of my pseudo-tourism became my utmost consumption, marking a creative zone of playful sociability — both immediate and mediate — with friends met online and offline [see figure 6].

When I was re-enacting, word-by-word, the performance of my gay neo-Nazi interlocutor I started wondering if were shared qualities other than being ‘gay’. Could ‘homo’, which in Greek also refers to sameness/similarity (omoiothta), include something more than sexual orientation? Is there something in common between an Athens-based neo-Nazi and a gay, semi-unemployed academic/artist?

This interrogation pointed immediately towards a cliché interview question usually addressed to Hollywood stars: ‘So, mister-famous-and-talented-person, do you have something in common with the character you impersonate?’ A central feature of the neo-Nazi character — as was presented in both my art practice and art writing — was his tendency to stage a sui generis spectacle of fear on digital and sexual stages. In his show, Facebook combined the interactive vigour of a theatrical experience with the magical distance of a cinematic screen. It now seemed that the post-cinematic thirst for stardom was not limited to one person or one only performance. It also involved my own ‘act’ when re-enacting the performance of my violent interlocutor.

This awareness inspired a more elaborate rephrasing of this question: Is there something in common between gay Nazi who stages his cinematic splendor on Facebook and a gay precarious academic who makes a show out of his aggressor — while struggling to survive in an increasingly aggressive environment?

The response was affirmative: there indeed seems to be a commonality, a type of ‘homo’ that connected me to him — or, at least, his performance and my re-enactment of it. And the best phrase to describe this is ‘horny despair’. I understand ‘horny despair’ as the tendency to transform pain into horniness and horniness into despair when feeling defeated, whether professionally, erotically, or creatively. When I performed someone else’s defeat and anger using my own body, these types of defeat felt interconnected. As a result, the next phase of this artistic endeavor was to investigate these links and find a way of displaying them.

This led to a new series of practical and theoretical inquiries. Can I use this same this same persona, this same body, this same stylistic outfit in order to sexualize anger in a different way? Is it possible to retain this lust for fight and this fight for lust without resorting to non-consensual forms of violence and hatred? And finally, how can I use the cinematic stage of Facebook in order redefine my war, my weapons, and my enemies?

It is worth discussing my response to these questions, by focusing on a series of pictures that I shared on Facebook, from August 2014 onwards.

This gesture was meant to destroy the boundaries between analysis and action, theory and practice, past and present. The memoir of defeat became an act of professional self-sabotage. Ephemeral Facebook memories were now presented as professional output. Academic conferences and social media are both places destined for networking. Instead of polite forms of self-introduction and clichéd tropes of socialisation, such as ‘your paper was very interesting’, my ritual of self-exposure aimed to show that ‘artistic’ pleasure could be experienced through playful attacks on formality — or else, through unexpected responses to the communicative rituals of networking. Art here is the capacity to create suspense, risk, emotion, destabilisation, and ambiguity — or, at the very least, a sudden mix of humiliation and pride in the midst of boring, formalised, or mundane environments. Conferences, galleries, and touristic landscapes are all environments that dictate material, psychological, and creative ways of being in your body. Based on numerous written and unwritten rules, these sites of socialisation and survival can both reject (and more rarely celebrate) insubordinate or unconventional forms of behaviour. The act of playing ‘risky’ games in these environments creates a new form of pleasure, as well as a new mode of knowledge through pleasure.

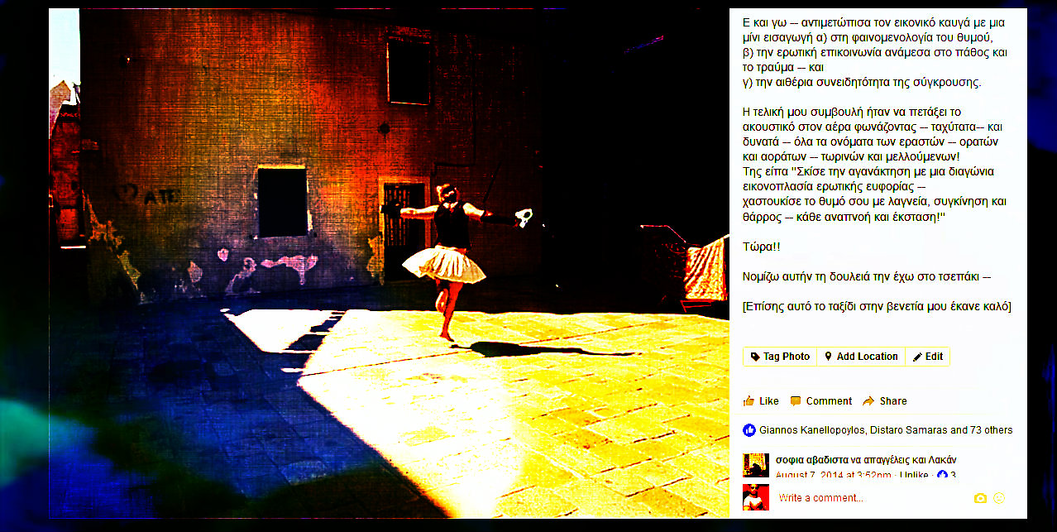

This mix of playful hedonism and self-sabotage was not limited to striptease: I then proceeded to explain that beyond T-shirts, there was still a way to make an art out of these pictures — as long as there was access to a Facebook account. There it would possible to create an unusual collage of horny despair: the Venice photograph printed on my CV was creatively paired online not with a description of the disturbed holiday-memoir but with a different story of defeat; namely, a job-interview that went terribly wrong. This was an interview for a type of work that, as I explained to my academic audience, could potentially bring me into contact with people eager to use brutal styles of communication, similar to the ones used by neo-Nazi aggressors. Clients could call me names such as ‘faggot, wanker or cocksucker’. This was a type of work that would require excellent anger management skills. My expertise in the aesthetics of crime would provide valuable transferable skills, especially my willingness to see confrontation as a form of art. This job was none other than a zero-hourly position of customer advisor. Posted side-by-side with the Venice holiday picture, the story of this deranged interview was narrated in the following way:

I just finished a phone interview for the post of customer adviser for a media company.

Customers will call me in order to curse and complain — so an integral part of our discussion involved a role-playing game. The interviewer played the angry customer. She wanted to check how I would react in a confrontational situation.

I responded to this whole virtual fight with a mini-introduction to:

a) the phenomenology of anger;

b) the sexual encounter between passion and trauma;

c) the ethereal consciousness of conflict.

In my final piece of advice, I encouraged my interlocutor to throw her handset in the air shouting fast and loud all the names of her lovers — visible and invisible — current and future ones — human and alien.

I actually told her, ‘Tear your indignation with a diagonal imagery of euphoria —

slap your anger you with lust, excitement and courage — follow every new breath as a new journey to ecstasy!’

Do it — now

I have this job in my pocket.

August 2014. Facebook.

Of course, I lost that position. Inspired by an actual job interview that went wrong, the above story is not an accurate account of events. Rather, it articulates the words, ideas, and feelings that were left unspoken during that process. Most importantly, it creates a sense of triumph out of an experience of defeat. This hedonistic reworking of loss connects all these different types of stories, performances, and media that transformed The Homonazi Effect into a polymedia provocation. All these cycles of expression exemplify what I understand as ‘the art of existential sodomism’. If some of us can turn sodomism into orgasm, then it might be also possible to transform pain — material, psychological, physical pain — into a form of pleasure. This is not a passive, over-positive, self-help acceptance of the world as it is, nor is it meant to suggest that if the world abuses you, you should relax and enjoy it. The point here is to fight back by inventing new languages of joy, new canons of beauty, and ultimately new ideals of professional, moral and social success.

How is it possible to accomplish this in this highly profit-driven narcissist kingdom of digital self-observance and political conformism? The answer to this question resonates with the question posed earlier: how is it possible to make people understand Facebook humiliation as a form of art? At this point, it is worth admitting that the ostensibly distinct questions, ‘how to exhibit this art?’ and, ‘how to understand this art?’ overlap. Beyond the material challenges of exhibition and curation, there needs to be a conceptual shift, a change in the way we understand and read the dialogue between art and social media. In fact, this conceptual reorientation is an ingredient of this artistic process. There are five focal points in this rethinking that can point us towards this direction: a) the idea of art as process (and not merely an object or a representation), b) the political aesthetics of Facebook and social media, c) the understanding of queerness as an art of life, d) familiarisation with the materials and topographies of new media/social media art. Without providing an exhaustive literature on this topic, the following section addresses key questions in these debates and explains how they interrelate with the stories, acts, and ideas of How to Use Gay Nazis in Job Interviews. Before addressing the theoretical premises of this artwork more detail, it is worth drawing on an online memory, a ‘queer’ manifesto. This was posted on Facebook long before the video-performance. The discussion of its ideas will help explore how the presentation of an idea online can be both experienced and theorised as a form of artistic gesture — or simply, as a form of pleasure in a world devoid of pleasures.

Click here for the following section -- Queer Precarity and the Digital Epistemology of Chaos