Anyone familiar with research in the human sciences knows that, contrary to common opinion, a reflection on method usually follows practical application, rather than preceding it. It is a matter, then, of ultimate or penultimate thoughts, to be discussed among friends and colleagues, which can legitimately be articulated only after extensive research.

(Agamben 2009, 7)

Introduction

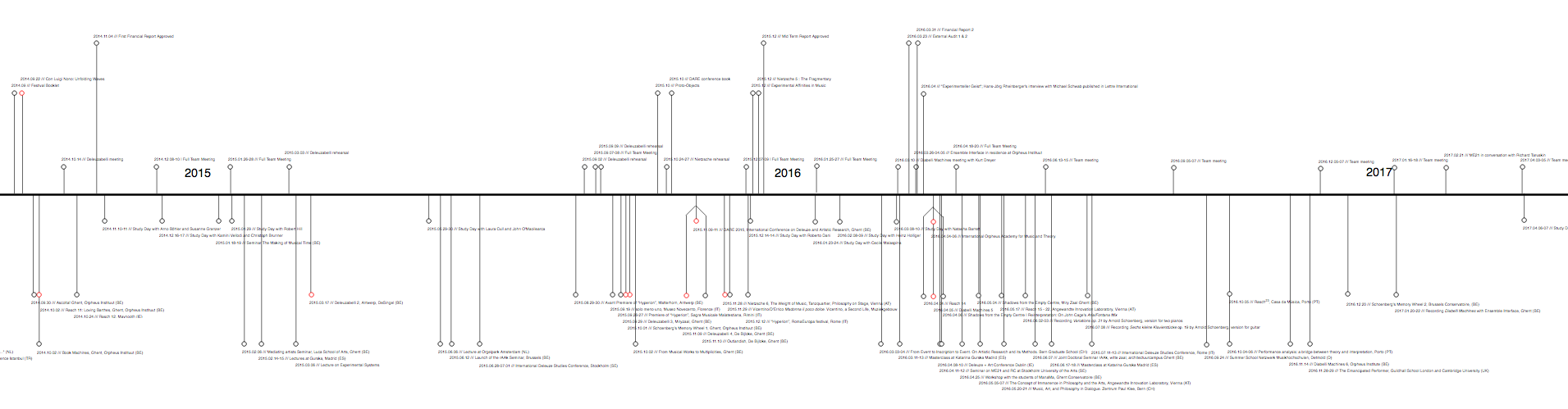

MusicExperiment21 (ME21) is a five-year artistic research programme (2013-2018), funded by the European Research Council and based at the Orpheus Institute, in Ghent (BE). The project explores and develops notions of “experimentation” in order to challenge dominant performance practices of Western notated art music. It brings together different artistic, historical, methodological, epistemological, and philosophical approaches that contribute to a new experimental attitude, crucially moving from interpretation towards experimentation—a central term that is not used in relation to measurable phenomena, but rather to a willingness to constantly reshape thoughts and practices, to contribute to new redistributions of the sensible, particularly affording unpredictable reconfigurations of music.

More concretely, MusicExperiment21 is generating new modes of music performance, innovative approaches to historical materials, and exploring new media for the exposition of artistic research in music. Inspired by Deleuze and Guattari’s discourse on strata (cf. Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 553-556), and remaining aware of the unavoidable anisomorphism between philosophy and art, one can identify six types of strata in those music materials that physically exist in the real world: parastrata (treatises, manuals, iconography, period instruments, descriptions of concerts, critics, archives, lists of personnel, payments, etc.), substrata (sketches, drafts, first editions, letters, writings by composers and performers, annotations, etc.); epistrata (period editions, editions throughout time, analysis, reflexive texts, theoretical contextualizations, recordings, etc.); metastrata (future performances, expositions, recordings, transcriptions, etc.), and allostrata (materials that not directly relating to a given work can enter productive relationships with it). In music, these strata are not only being added and superposed in a linear progression—they infiltrate or contaminate each other throughout time, generating interstrata: complex arrangements of forces and intensities. By focusing on these innumerable documents, ‘works’ are being considered as historically constructed conglomerates of things. In this sense, works can be seen as meta-assemblages, since all of their constitutive things are in themselves concrete machinic assemblages (editions, recordings, essays, performances, etc.).

Methodologically, this perspective allows for a three-step modus operandi, which is being developed by MusicExperiment21: first, the innumerable material traces and things are archaeologically identified and retrieved for further consideration; secondly, the relations and connectors they entertain with each other, as well as their transmission throughout time, are studied in terms of a genealogy, disclosing singularities, i.e., particular points of high energy or concentration of forces; and finally, specific selections of things are brought together as "concrete machinic assemblages" (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, 555) that problematize them anew. The archaeological moment relates to conventional scholarly research, including archival and sources studies; the genealogy calls for interpretation, semiotics and transtextuality; and the problematization happens by constructing new and experimental machinic assemblages. With the latter, the artistic dimension becomes inescapable, and it requires the kind of artist and the kind of researcher that can cohabit the same body—something like Nietzsche’s vision of the ‘artist-philosopher’ – or, in our current language, the ‘artistic researcher’.

By integrating into performance materials that go beyond the score (sketches, texts, concepts, images, and videos), these interwoven methodologies offer a broader contextualization of works within a transdisciplinary horizon. At the same time, they also allow for new modes of conducting research in music and for thinking composition and performance as knowledge producing activities.

Epistemologically, MusicExperiment21 appropriated Hans-Jörg Rheinberger’s notion of “experimental systems” for music, and this exposition aims at specifying the context, rationale, and main characteristics of such appropriation. It is important to note that this publication is not intended as a description or as an explanation of Rheinberger’s experimental systems; nor is it an account of ME21’s artistic projects. It is about the relations between the two, between artistic-research events/activities and their configuration in terms of experimental systems.

It must be stressed that inside MusicExperiment21 there are two complementary approaches to Rheinberger’s theories. On the one hand, Michael Schwab—the responsible for the project’s epistemological strand— investigates the wider epistemological consequences of such systems, particularly focusing on how to adapt experimental systems for contemporary art. While Rheinberger’s experimental systems discuss the spaces of experimentation and the spaces of representation, Michael Schwab situates contemporary art in the graphematic space, not in the representational—as it might still have been the case, arguably, for modern art (cf. Schwab 2015). In this line of thought, Schwab links Rheinberger’s experimental systems to his own concept of “expositionality” (cf. Schwab 2014a). Notions such as the fragmentary, the untimely, or the contemporary are, therefore, central to his approach, which aims at looking at transformations both in the work as well as in the system itself. This research focus produced important events and outputs, such as a study-day (Orpheus Institute, 5-6 July 2012) and an interview with Rheinberger (Schwab 2013b), a research questionnaire (Schwab 2014b), and the collective volume Experimental Systems—Future Knowledge in Artistic Research (Schwab 2013a).

On the other hand, Rheinberger’s experimental systems have been practically used for the design of the artistic-research experiments, leading to a great number of artistic-research outputs. This approach is more focused on the concrete conditions of the experiments and on the generation of differential repetition. It looks at the distinction between “technical objects” and “epistemic things”, between space of experimentation and space of representation, and at the question of multimedia inscriptions resulting from and at the same time generating new modes of presenting artistic research. This approach has been designed and developed by myself since the beginning of MusicExperiment21. The present exposition is the first public communication of this particular mode of working. A perfectly integrated discussion of both approaches must be left to future work, especially as ME21 is not yet finished and it seems most productive to keep some distance between the two approaches.

This paper is organised in five sections: the first—Modes of Research—, situates MusicExperiment21 in terms of existing typologies of research and knowledge production, referring to Mode 1 and Mode 2 science, to basic and applied research, and to quantitative and qualitative research methods. Artistic research appears as a form of critical research, functioning as a hybrid mode: it shares some aspects with Mode 1 and Mode 2, while proposing alternative methodologies. The second section—Rheinberger’s Experimental Systems—, offers a brief overview on the notion of experimental system, making some terminological specifications, and suggesting modes of appropriating such systems for artistic research. In the third part, MusicExperiment21 is presented as a “thought collective” and as an ensemble of experimental systems. The fourth section—Epistemic Complexity in Music—, briefly introduces MusicExperiment21’s innovative understanding of musical entities as complex agencements (assemblages) of innumerable material “things”, preparing the reader for the project’s use of the notion of experimental system. In the fifth and last section—Series and Modules—, the diversity of aesthetic and research practices is displayed through the use of “series” of aesthetic-epistemic experiments, and by the consistent use of “modules” of research, each resulting from a different research method or perspective. In this section the notions of differential repetition, space of experimentation, and space of representation are presented in relation to their use by MusicExperiment21.

Series of Experiments and Modules of Research

In 2014, Michael Schwab, noted that “over the last years, Hans-Jörg Rheinberger’s theory of ‘experimental systems’… has gained currency in the debates around art and research…[however] it is striking that in the literature to date, no coherent picture has emerged as to how his theory may productively be employed in this context. (…) Authors who focus on the epistemological implications may identify ‘epistemic things’ within artistic practice, while failing to account for the specificity of experimentation in this context.” (Schwab 2014, 31). In that same text Schwab addresses the relation between Rheinberger’s notion of experimental systems and his own concept of ‘exposition’, which is defined as “the exposition of practice as research” (ibid., 35), insisting on the link between Rheinberger’s graphematic space of experimentation and the inherent graphematicity of the Research Catalogue, a web-based platform for the exposition of artistic research.

MusicExperiment21 established a practice, which is based upon a specific take on Rheinberger’s experimental systems. Significantly, this practice comes to the fore at the level of the daily practice of the team and of the public performances done by the ME21 Collective **.

A pragmatically oriented methodology has been put in place, based upon five basic ideas:

- A choice of the fundamental research objects/things for every case study or sub-project was rigorously made, taking into account their potential to act sometimes as a technical object, other times as epistemic thing;

- Every sub-project or case study systematically generates differential repetition of some kind;

- In order to enhance this differential repetition, every case study is presented in series of experiments, which are numbered according to specific parameters;

- Every sub-project is presented in as many and diverse modes as possible through different modules of research, each resulting from a different research method or perspective;

- Last but not least, the Research Catalogue is massively used, being (in addition to the concert stage) ME21’s main channel of experimentation and representation.

Thus, using Rheinberger’s experimental systems as a reference, ME21 developed a sort of musical lab, sustained by series of experimental performances that contribute to a substantial turn away from conventional performance practices and musicological methodologies. In all case studies, projects, and sub-projects ME21 insists on the precise definition of the technical objects and epistemic things at play. Considering them as parameters within an experimental setup allows for differential combinations, regulations, and calibrations of material things and affective forces. The spaces of experimentation and representation are often intermingled; however, as a starting position the spaces of experimentation are considered to be the physical spaces of the host institution, the music halls and art galleries where ME21 performs, while the spaces of representation are books, journals, commercial CDs, and websites. In this respect the Research Catalogue takes a particular position, being at the same time a space of experimentation and a space of representation. It is used to store, archive and document research, but also as a working tool, a virtual space where research is produced like at the researcher’s working desk. An example of such use can be seen in Michael Schwab’s entry The Exposition of Practice as Research: Talks, Conferences, Workshops.

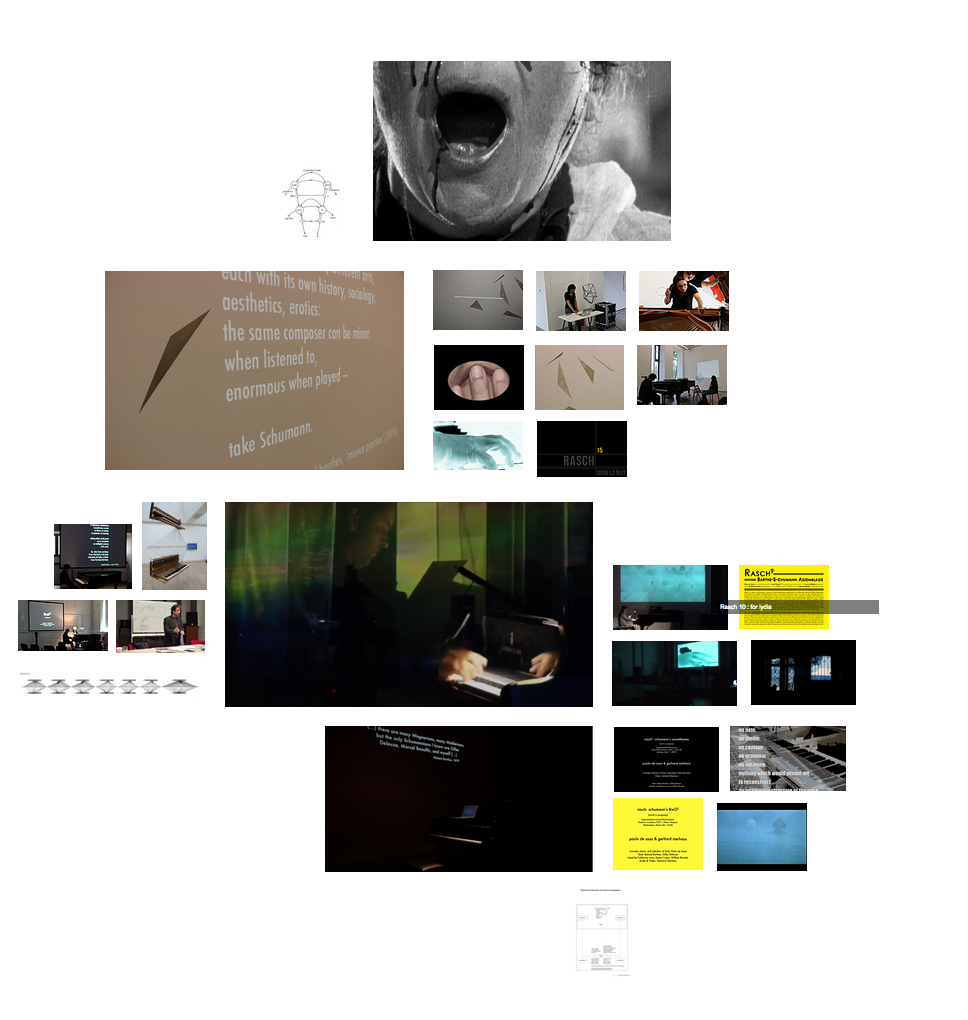

A first example was already presented above. Con Luigi Nono—Unfolding Waves illustrates the modular model of doing and exposing research. As for the principles of “seriality” and “differential repetition” Rasch X is the perfect example. It consists of a potentially infinite series of mutational performances based upon two basic materials: Robert Schumann’s Kreisleriana op. 16 (1838), and Roland Barthes essays on the music of Schumann (1970, 1975, 1979), particularly ‘Rasch’, a piece of writing exclusively dedicated to Schumann’s Kreisleriana. To these materials other components may be added for every single particular version: visual elements (pictures, videos), other texts, or further aural elements (recordings, live-electronics, etc.). The main goal is to generate an intricate network of aesthetic-epistemic cross-references, through which the listener has the freedom to focus on different layers of perception: be it on the music, on the texts being projected or read, on the images, on the voices, etc. Situated beyond “interpretation”, “hermeneutics”, and “aesthetics” the twenty-four instantiations (so far) of Rasch X have been emblematic for what might be labelled as experimental performance practices. These practices productively deviate from conventional (repetitive) performative strategies transforming familiar artistic objects into objects for thought.

Other examples include the seven instantiations of the Diabelli Machines and the various Anamorphic Simulacra produced by Lucia D'Errico in the framework of her doctorate in artistic research.

Draft document [version 24.04.2017] // This paper was presented and discussed at the International Conference on Artistic Research: "Please Specify! Sharing Artistic Research Across Disciplines" // Helsinki 29 April 2017, Parallel Sessions II, 2E: Experimentation // 11.30-13.15. The session was chaired by Michael Schwab and attended by Hans-Jörg Rheinberger, Henk Borgdorff, Frans de Ruiter, Alexander Damianisch, Kamini Vellodi, Esa Kirkopelto, Tero Nauha, and Mika Elo, a.o.

Experimental Systems in Music

Specifying MusicExperiment21’s use of Rheinberger’s Experimental Systems

Paulo de Assis

Orpheus Institute Ghent, BE

Modes of Research

MusicExperiment21 operates under the sign of a new kind of science and of a new way of understanding aesthetic-epistemic practices. Moving between Mode 1 science and Mode 2 knowledge production (for these notions, see Gibbons et al 1994; Nowotny et al 2003, 179-80-81; Borgdorff 2012, 91-100), ME21 produces varied forms of distributed knowledge, which are context-sensitive, transdisciplinary, heterogeneous, and peer-reviewed by an extended pool of experts coming from different fields of activity. Classical partitions between basic and applied research, or between qualitative and quantitative research can still be recognized in specific parts of the sub-projects developed by ME21, but a crucial aim of this project is precisely to problematize conventional modes of research and to suggest alternatives.

In the particular case of music, standard approaches like historical or systematic musicology, performance studies or cognitive sciences have strong disciplinary limits, not necessarily helpful to a productive exploration of musical objects, for creative performances, or to the development of new solutions for music making. While traditional forms of research are certainly still important, new modes of producing knowledge—based upon principles of transdisciplinarity, heterogeneity, transience, social reflexivity, context-dependence, and most importantly conducted by artists and practitioners—are generating important results, contributing to a redefinition of what counts as research. From an epistemological point of view, one of the goals of MusicExperiment21 is to contribute to the development of concrete artistic research methodologies and innovative modes of communicating knowledge that include aesthetic components.

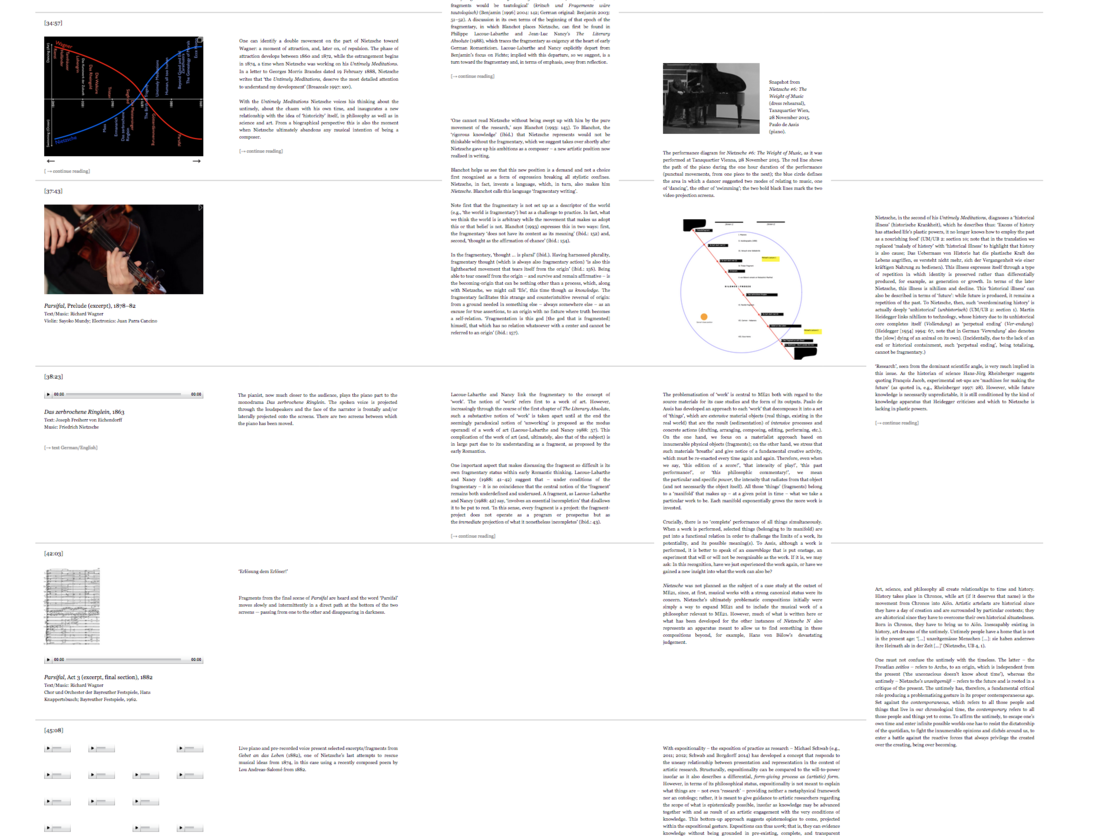

To give an introductory example, one can look at the first “official” output of MusicExperiment21, a peer-reviewed article published in the Journal for Artistic Research in 2014. Con Luigi Nono—Unfolding Waves is organized around a modular structure with a very simple idea: to show the fluidity, flexibility, and continuity of the borders between “academic” and “artistic” practices and outputs. The numerical sequence of the modules (1 to 7, or left-to-right as they appear in the entry page) indicates a progressive displacement from “factual” historiographical and analytic data to “creative/imaginative” appropriations of the researched materials. Thus, Module 1 is mainly historiographical, Module 2 archaeological, Module 3 and Module 4 analytical, Module 5 interpretative, Module 6 and Module 7 creative and exploratory. On the one hand, the modules move from “more scholarly” towards “more artistic”; on the other hand, each module enacts a different balance between these polarities, stressing the fact that there cannot be a “pure” scholarly approach (without any creativity), nor can there be any “pure” artistic practice (without any contextualization and references). Additionally, the “writing” within the exposition is also experimental. Different modules have different types of writing, including conventional musicological discourse (Modules 1 and 6), spoken presentation (Module 2), diagrammatic inscriptions (Modules 3 and 4), and absence of text altogether (Modules 5 and 7).

In relation to writing as a research practice it is worth mentioning another peer-reviewed publication done by MusicExperiment21 Nietzsche 5 : The Fragmentary (Schwab and De Assis, 2015, Ruukku 5), where writing is also experimental, yet with a completely different approach, enhancing the fragmentary character of the research object. Thus, ME21 is experimenting with context-situated solutions, looking for suitable formats and not aiming at developing solutions that could fit all case studies.

Central to MusicExperiment21 is Michel Foucault’s notion of problematisation, which implies a positive conception of problems, and which fundamentally transforms “objects” into “objects for thought”. Foucault’s perspective impacted ME21 in several ways, but importantly in two: on the one hand, the transdisciplinary proliferation of research approaches is bound up with the problematisation of research itself; on the other hand, transdisciplinary research in specific fields may both respond to, and lead to the generation of unexpected problems. As for the first point, and in the specific case of Con Luigi Nono—Unfolding Waves, different types of research were used in the exposition: historical research informs Modules 1 and 2; descriptive research, Modules 3 and 4; Module 5 can be seen as an example of experimental research and of phenomenological research; finally, Modules 6 and 7 are based upon exploratory research. Therefore, the exposition—as a whole—addresses the growing proliferation of research methodologies, arguing for a pluralistic research practice. Regarding the second aspect, the generation of new problems, Con Luigi Nono—Unfolding Waves acted as a case in point for MusicExperiment21’s ongoing development of alternative music ontological accounts and methodologies. Only after having finished (and published) its online exposition did it become clear to the research team that a new “image of musical work” needed to be further investigated, defined and elaborated.

MusicExperiment21 is, thus, doing “critical research”, research that aims at challenging—and hopefully changing—dominant systems and regimes of organizing research itself. Sometimes also labelled as “radical research” or “emancipatory research”, critical research points to epistemological* ruptures, potentially leading to alternative epistemic configurations.

From another angle, MusicExperiment21 is also very much interested in post-Kuhnian understandings of science, which are not primarily theory-based or theory-driven, but that seek to concretely unravel the actual processes of science-making through experimentation. In this sense, Rheinberger is obviously a major reference. At the very beginning of his book Toward a History of Epistemic Things one reads that: “In a post-Kuhnian move away from the hegemony of theory, historians and philosophers of science have given experimentation more attention in recent years. This book is an attempt at an epistemology of contemporary experimentation (…)” (Rheinberger 1997, 1). By situating scientific practices and research methodologies in their respective historical times, Rheinberger closely addresses the problem of historicizing epistemology, which so crucially contributed to a movement from science-as-a-system to science-as-a-process (cf. Rheinberger 2010, 1). This change happened in parallel to a profound shift of interest from a system of knowledge production based upon the finding and presenting of a “correct” scientific method, to a more concrete interest “in what scientists actually do in pursuit of their specific research” (ibid., 3). Instead of “testing theories”, research happens on a daily basis, through the concrete (an still most often) manual manipulations of objects. Researchers appear as “doers”, not as illuminated academics delivering proof of a given theory.

It is within these broader frameworks of interest (hybrid modes of research and materially based experimentation) that Rheinberger’s notion of experimental systems became so central to the concrete practice of MusicExperiment21, providing a basic modus operandi to the team and to the design of the overarching research strategy.

References

Agamben, Giorgio, 2009. The Signature of All Things—On Method, New York: Zone Books.

Barry, Andrew and Georgina Born, 2013. Interdisciplinary. Reconfigurations of the Social and Natural Sciences, London/New York: Routledge.

Borgdorff, Henk, 2012. The Conflict of the Faculties. Perspectives on Artistic Research and Academia, Leiden: Leiden University Press.

Cohen, Robert S. And Thomas Schnelle (eds.), 1986. Cognition and Fact. Materials on Ludwig Fleck, Dordrecht/Boston/Lancaster/Tokyo: D. Reidel Publishing Company.

De Assis, Paulo, 2013. ‘Epistemic Complexity and Experimental Systems in Music Performance’, in Experimental Systems–Future Knowledge in Artistic Research, ed. By Michael Schwab, Leuven: Leuven University Press.

Deleuze, Gilles and Félix Guattari, [1980] 1987. A Thousand Plateaus — Capitalism and Schizophrenia, translated by Brian Massumi, London / New York: Continuum.

Fleck, Ludwig, [1935] 1979. Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Foucault, Michel, [1966] 1970. The Order of Things, London/New York: Routledge.

Gibbons, Michael, Camille Limoges, Helga Nowotny, Simon Schwartzman, Peter Scott and Martin Trow, 1994. The New Production of Knowledge: The Dynamics of Science and Research in Contemporary Societies, London: Sage.

Goehr, Lydia, [1992] 2007. The Imaginary Museum of Musical Works, New York: Columbia University Press.

Knorr Cetina, Karin, 1999. Epistemic Cultures. How the Sciences Make Knowledge, Cambridge MA/London: Harvard University Press.

Kubler, George, [1962] 2008. The Shape of Time: Remarks on the History of Things, New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Nowotny, Helga, Peter Scott and Michael Gibbons, 2001. Re-Thinking Science. Knowledge and the Public in an Age of Uncertainty, Cambridge/Malden: Polity Press.

Nowotny, Helga, Peter Scott and Michael Gibbons, 2003. ‘Introduction. “Mode2” revisited: The New Production of Knowledge’, in Minerva 41, 2003 (Kluwer Academic Publishers), 179-194.

Hans-Jörg Rheinberger's Experimental Systems

Rheinberger developed his theory of “experimental systems” in relation to the empirical sciences, particularly to molecular biology. However, it was Rheinberger himself who opened the door for other potential uses of this notion, specifically, for example, in relation to the activity of writing: “Writing is an experimental system in its own right” (Rheinberger 2007, my translation). Taking this line of thought further, that MusicExperiment21 proposes an extension of experimental systems also to the performance of past musical works. Before describing this musical appropriation of experimental systems, what follows is a brief overview of what experimental systems are.

According to Rheinberger, his book Toward a History of Epistemic Things is “an attempt at an epistemology of contemporary experimentation based on the notion of ‘experimental system’” (Rheinberger 1997, 1). Originally taken from the everyday practice and vernacular of mid-twentieth-century life scientists, the concept of “experimental system” is frequently used to characterise the space and scope of the research activities conducted by researchers in biochemistry and molecular biology. Importantly, this is, in the first place, a practitioner’s notion, not an observer’s (see Rheinberger 1997, 19). In his most succinct formulation, Rheinberger states that “experimental systems are arrangements that allow us to create cognitive, spatiotemporal singularities” (ibid., 23). More specifically, experimental systems are characterised by four main features, which Rheinberger thoroughly described in several occasions—notably in the “Prologue” to the book Toward a History of Epistemic Things (1997) and in the online essay Experimental Systems: Entry Encyclopedia for the History of Life (Rheinberger 2004). In short, such features are the following:

- An experimental system is a specific unit of research, spatiotemporally precisely located, wherein two kinds of “things” interact: technical objects and epistemic things (whose difference is functional and not ontological).

- Within such a system, mechanisms of reproduction and repetition aim at the generation of differences.

- An experimental system is a space of representation where inscriptions are made in order to generate and preserve traces.

- Finally, experimental systems might establish links to other experimental systems (conjunctures), be divided into several experimental systems (bifurcations), or merge with other experimental systems (hybridisation). At some point an articulation of ensembles of experimental systems might emerge, generating what Rheinberger calls experimental culture (cf. Rheinberger 1997b, 3).

Terminologically, and to avoid conceptual misunderstandings, some explanation of terms is necessary here. First, Rheinberger’s use of the term system does not relate to an enclosed, perfectly defined set of rules and axioms, but “simply a kind of loose coherence both synchronically with respect to the technical and organic elements that enter into an experimental system and diachronically with respect to its persistence over time” (Rheinberger 2004, 3). Furthermore, the notions of technical object and epistemic components reveal that technicity and epistemicity are not ontologically opposed to each other, but form an intricate relation at the inner core of an experimental system. Epistemic things are the entities “whose unknown characteristics are the target of an experimental inquiry” (Rheinberger 1997b, 238), paradoxically embodying what one does not yet know (cf. ibid., 28). Technical objects (sedimentations of earlier epistemic things) are scientific objects that “embody the knowledge of a given research field at a given time” (ibid., 245); they might be “instruments, apparatus, and devices which bound and confine the assessment of the epistemic things” (Rheinberger 2004, 4).

Epistemic things are necessarily underdetermined, while technical objects are characteristically determined. Technical objects and epistemic things coexist simultaneously within the experimental system, and “whether an object functions as an epistemic or a technical entity depends on the place or “node” it occupies in the experimental context” (Rheinberger 1997b, 30); “within a particular research process, epistemic things can eventually be turned into technical things and become incorporated into the technical conditions of the system” (Rheinberger 2004, 4). Between the two extremes, there is room for a gradient scale, for diverse degrees of hybrid things, and for vague material entities whose function in the experimental system changes. An example of such an entity, when applying these notions to music, is the score, the material inscription of a complex set of signs and symbols that might be considered as either an epistemic thing or a technical object depending on the role it plays at any particular point during the compositional process, the research moment, its performance, or its recording.

When appropriating experimental systems for the arts, what is at stake are the epistemic qualities of art, and not an understanding of art as science, or of art as an object for science. When using the term “epistemic thing”, Rheinberger clearly was avoiding using “scientific thing”, denoting that these “things” are not independent from the resources and media that allow them to exist. (Rheinberger 2008, 13’30”-13’45”). For artistic research, the most important questions are not related to quantifiable data, nor to phenomenological subjective observations. Artistic research in music should not be addressing measurable phenomena, which are the domain of performance science, performance studies, organology, philology, historiography and applied musicology. The crucial questions of artistic research are of a different nature, involving the epistemic power of art and its transformation from an object of aesthetic appreciation to an object of and for thought. These are the concerns that have the potential to redefine artistic practices, to generate conjunctures, bifurcations, and hybridisations of forms and materials.

On the other hand, the four basic characteristics of experimental systems, all taken together, enhance the constitution of “thought collectives” (Denkkollektiv), a term coined by Ludwig Fleck in 1935 to which Rheinberger often refers. Such thought collectives, each with a special “thought style” (Denkstil), are fundamental to the production of knowledge in artistic research, moving beyond the individual “genius” to more distributed modes of creativity and reflection, which liberate the production of knowledge from disciplinary compartmentations. They extend practice and reflection beyond disciplinary thinking, avoiding what Bachelard called the “cantonisation” of science.

MusicExperiment21

MusicExperiment21’s application of Rheinberger’s terminology is an attempt to establish a wider horizon of practice for artistic research in music. This application is not obvious, nor is it straightforward. Rheinberger developed his theories in a very specific field of inquiry. In transferring these theories to other fields (especially to artistic and creative areas), one must proceed cautiously, though having the courage to do it. In fact, there are several musical entities that might be considered as being technical objects and/or epistemic things, depending on the specific use and context of their presentation. Accepting the risk incurred in applying Rheinberger’s theories to music, one might say that scores, instruments, or tuning systems, for instance, may be seen as technical objects that are brought into particular constellations (such as “the concert” or a CD recording), to produce art. The same entities may, however, operate as epistemic things, whose qualities can be divided into two main groups: those already known and those still to be known (discovered or invented). Musical works participate, therefore, in two different worlds: one related to their past (what constitutes them as recognisable objects), another related to their future (what they might become). If we require performance to be an idealised act of interpretation, and if we reduce it to the repetition of the score (understood as an instrumental technical object), we take away the possibility for epistemic things to emerge or to unfold into unforeseen dimensions. We would be dealing mainly with the work’s past. If we want to give credibility to performance as an instance of epistemic activity, we need a concept such as “experimentation”, which creates space in relation to the score, allowing unpredictable futures to happen. From this perspective, experimentation, methodologically conducted through experimental systems, might allow for “making the future” of past musical works, something of which “interpretation” is far less capable. Moreover, artistic experimentation has the potential to bring together the past and the future of “things”, enabling and concretely constructing new reconfigurations—something that non-artistic modes of knowledge production can only partially do.

MusicExperiment21 is a thought collective, a group of artist-researchers working together, mainly within the spaces of the host institution, but also through web-based platforms. The project was designed by myself, back in 2011, when the grant proposal was submitted to the European Research Council’s Starting Grant programme (November 2011). Between the submission and the second stage interview, seven months passed, and seven months more before the official start of the project (February 2013). We are now in the last year of the programme, which will end in January 2018, which means that the original design lies six years behind. On the other hand, only now, after having completed most of the research deliverables, after creating new modes of doing artistic research are we in a position to distance ourselves and critically reflect on the employed strategies and methodologies. As Giorgio Agamben writes, ”a reflection on method usually follows practical application, rather than preceding it.” (Agamben 2009, 7).

Placed within the Orpheus Institute (Ghent, BE), ME21 is part of a wider research community and endeavour, being one among other projects in artistic research that are aiming at practically contributing to a better definition of the burgeoning field of artistic research in music. In this sense, ME21 is already part of a research culture, part of an ensemble of other research projects that might be seen as experimental systems in their own right. Moreover, the Orpheus Institute is an example of that “reconfiguration of institutions” that is usually associated with Mode 2 knowledge production, the institute not being a university, nor a conservatoire, but a hybrid space exclusively devoted to artistic research in music. This puts pressure on the researchers, who have to publish as if in a university set up, while at the same have to perform as if independent musicians or professors in higher music education schools. At the same time, such pressure is positive, enabling and enhancing alternative ways of doing both research and artistic practice.

Internally, ME21 is also organised as an ensemble of experimental systems: it includes several case studies, each of which with its own system, and it has different people focusing on different topics. At the beginning it had four artist-researchers (the Principal Investigator, two senior postdocs, and one early stage postdoc), a number that grew up to fifteen by the middle of the project (external consultants with artistic or musicological expertise), until it stabilised in a core team of six people, including the PI, two postdocs, and three doctoral students. The project created its own performative ensemble (ME21 Collective, founded 2014), and established artistic collaborations with leading international ensembles, such as the WDR Symphony Orchestra Cologne, the Hermes Ensemble (Antwerpen), and the Ensemble Interface (Frankfurt).

Epistemic complexity in music

From an overarching conceptual viewpoint, one of the main gestures of ME21 is a completely renewed ontological definition of those entities traditionally referred to as “musical works”. After two centuries in which the “work-concept” defined, regulated, and policed musical practices (cf. Goehr [1992] 2007), MusicExperiment21 has turned attention to what may be called work-as-assemblage, taking into consideration the dismantling of musical works into their graspable constitutive elements, revealing them as complex accumulations of singularities, and as multi-layered conglomerates of “things” with the utmost diversity. The closer one gets to such constitutive things, the clearer the epistemic complexity of musical works and performances becomes.

The description and explanation of my proposed “new image of work” would require much more space and shall not be addressed in this paper. Very succinctly, it conceives those entities as highly elaborated, complex semiotic artefacts with intricate operational functions, and made of a variable number of constitutive parts. Their invention, sedimentation, transmission, and their concrete performance involve forms of pre- and post-knowledge. They have a mode of existence which is similar to what Gilles Deleuze calls agencement (a word problematically translated into English as assemblage), and are better conceived as potentially infinite collections of things, which are always reconfigured for specific uses and appropriations. MusicExperiment21 makes such reconfigurations more visible, giving them a systematic approach and a practice based methodology.

Musical assemblages are encapsulated within specific epistemic settings, which are made of ample accumulations of historically produced (and inherited) materials, such as sketches, drafts, first editions, recordings, or essays. From the perspective of a performer dealing with a musical work from the past, types of relevant objects loaded with variable degrees of epistemic complexity include:

- Materials existing in the world prior to the composition of a given piece (treatises, manuals, codes, conventions, etc.)

- Materials generated by the composer (sketches, drafts, manuscripts, first prints, revisions of prints, etc.)

- Editions of a piece throughout time

- Recordings

- The reflective and conceptual (musicological, philosophical, analytical, etc.) apparatus around musical pieces (including thesis, articles, books, etc.)

- The organological diversity; that is, the instruments in use (for example, historical versus contemporary)

- The performative/aesthetic “orientation” of the performer (historically informed practice, “Romantic interpretation,” “new objectivity,” “modernising approach,” etc.)

- Arrangements and transcriptions

- The practitioner’s own body, which is biologically, technically, and culturally organised

One important observation is that until quite recently many of the items in this list were not generally available since they were the “property” of an exclusive group of experts. In the current, increasingly democratised knowledge-society more and more people have access to them. The items on the list are just the main tokens of a musical work’s epistemic complexity and may be extended by potentially infinite further sub-tokens. They build a complicated network of things embedded with knowledge. At some point, they all were reifications or sedimentations of a specific creative or reflective situation.

Importantly, these items might assume different functions: (1) as well defined objects of inquiry (What are they? How many parts do they have? How do they function?) or (2) as borderless “things” for further inquiries (How can they become productive again? How can they build reconfigurations of the work they belong to? What futures do they enhance?). The first approach has to do with a work’s systemic complexity and mostly leads to measurable modes of research, while the second points toward epistemic complexity, leading to more speculative, therefore, much more creative modes of research. Including a productive “not-yet-knowing,” artistic research creates room for what is yet unthought and unexpected. Under this light, processes of becoming appear as more fruitful than statements of being. The fundamental incompleteness of any attempt to “close” or narrow down a human-made invention becomes the starting point for epistemic explorations. In the place of a clear-cut ontology of the artwork, we find an unfolding becoming of functional parts and things, where experimentation becomes the central artistic activity.

Rheinberger, Hans-Jörg, 1997. Toward a History of Epistemic Things. Synthesizing Proteins in the Test Tube, Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Rheinberger, Hans-Jörg, 2004. ‘Experimental Systems’, The Virtual Laboratory’, http://vlp.mpiwg-berlin.mpg.de/essays/data/enc19?p=1 [accessed 31 March 2017].

Rheinberger, Hans-Jörg, 2007. Historische Epistemologie zur Einführung, Hamburg: Junius.

Rheinberger, Hans-Jörg, 2008. ‘Epistemische Dinge, technische Dinge’, video recording, 58:57, Bochum Media Science Colloquium, 2 July, https://vimeo.com/2351486 [accessed 31 March 2017].

Rheinberger, Hans-Jorg. 2010. On Historicizing Epistemology: An Essay, Stanford, California: Stanford University Press.

Schwab, Michael (ed.), 2013a. Experimental Systems—Future Knowledge in Artistic Research, Leuven: Leuven University Press.

Schwab, Michael, 2013b. ‘Introduction’, in Schwab 2013a, 5-14.

Schwab, Michael, 2013c. ‘Forming and Being Informed—Hans-Jörg Rheinberger in conversation with Michael Schwab’, in Schwab 2013a, 198-219. Also published in German as ‘Experimenteller Geist—Epistemische Dinge, Technische Objekte, Infrastrukturen der Forschung—Hans-Jörg Rheinberger spricht mit Michael Schwab’, in Lette International, 112, Spring 2016, 114-121.

Schwab, Michael, 2014a. ‘The Exposition of Practice as Research as Experimental Systems’, in Artistic Experimentation in Music. An Anthology (ed. By Darla Crispin and Bob Gilmore), Leuven: Leuven University Press, 31-40.

Schwab, Michael, 2014b. ‘Artistic Research and Experimental Systems: The Rheinberger Questionnaire and Study Day. A Report’, in Artistic Experimentation in Music. An Anthology (ed. By Darla Crispin and Bob Gilmore), Leuven: Leuven University Press, 111-123.

Schwab, Michael, 2014c. ‘The Exposition of Practice as Research: Talks, Conferences, Workshops‘, Research Catalogue (2014) https://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/95500/217581/0/0 [accessed 04/04/2017]

Schwab, Michael, 2015. ‘Experiment! Towards an artistic epistemology’, Journal of Visual Art Practice, DOI: 10.1080/14702029.2015.1041719

*The terms “episteme” and “epistemology” are used by ME21 with a specific meaning. “Episteme” is understood in its Foucauldian sense (which Foucault introduced in his book The Order of Things, 1966), referring to the commonly accepted “unconscious” structures underlying the production of scientific knowledge in a particular time and place. It can be seen as the dominant “epistemological field” that forms and informs the conditions of possibility for knowledge to emerge and to be communicated in a specific time and place. As for the general term “epistemology”, ME21 follows the definition proposed by Hans-Jörg Rheinberger, and does not use it “as a synonym for a theory of knowledge (Erkenntnis) that inquires into what it is that makes knowledge (Wissen) scientific, as was characteristic of the classical tradition, especially in English-speaking countries. Rather, the concept is used here, following the French practice, for reflecting on the historical conditions under which, and the means with which, things are made into objects of knowledge.” (Rheinberger 2010, 2).

** ME21 Collective is composed of artist researchers involved in, or collaborating with the project MusicExperiment21. The collective is coordinated and directed by Paulo de Assis, and includes musicians, performers, composers, dancers, actors, and philosophers. It has no standard or even stable formation, and its modes of communication range from conventional formats such as concerts and installations, to lectures, publications, and web expositions.