Trenza (HD video, 55´, 2017) was produced after Un Atletismo Afectivo. It was first presented at BREAK THE RULES! El cine documental contemporáneo, una caja de resistencia, a symposium on filmmaking organized by Territorios y Fronteras at the University of the Basque Country in June of the same year. In this section, the text combines sequences from the film and discarded materials as well as photographs of works made during the production of the film. This gives way to a new reading of the work.

The festive experience the piece records is an annual occurrence I have been acquainted with since I was a child. As such, even though the technique, medium, and language differ, experiences such as the desire to belong to a space, my observation of its transformation, and artistic characteristics such as the dialogue between practice, rituality and play, remain constant.

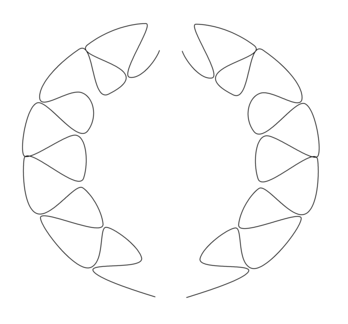

The desire to bond extends from my own experience to my observation of groups of young people as they conscientiously prepare the space in the two months leading up to the feast – an event that will only last a few hours. Their efforts during the summer months become a playful, collective task whose outcome – the feast – is completely uncertain. The same people repeat their actions every year so that staking out their space, maintaining it, and building and decorating their stands become rituals. The documentary proposes formal and procedural analogies between these rituals and that of the male bowerbird as it builds its folly for courtship.

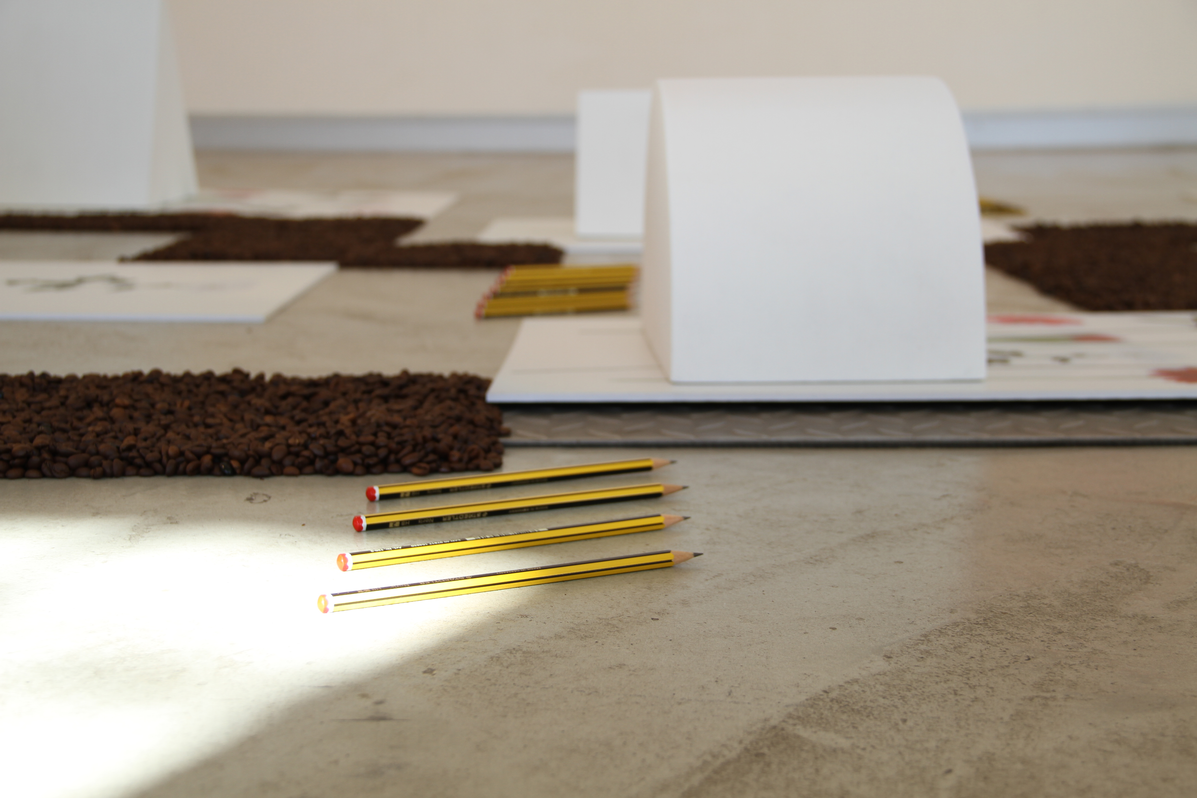

Trenza interweaves symbols such as lemons, coffee grains, flowers, pigment, pencils, and glitter, already seen in Un Atletismo Afectivo. This use of materials is seen in works such as Gimnasio esotérico and Lemonade, exhibited at the Fundación Bilboarte (July-August 2016), Sala Oxford, Zumaia (October-November 2016), and Getxoarte (November 2016).

During the piece’s postproduction, I recorded the final sequence of the film in which I appear with my back to the camera, braiding my own hair – a new gesture that gives rise to a symbol, which is artistically developed over the following months (see the section Braiding oneself).

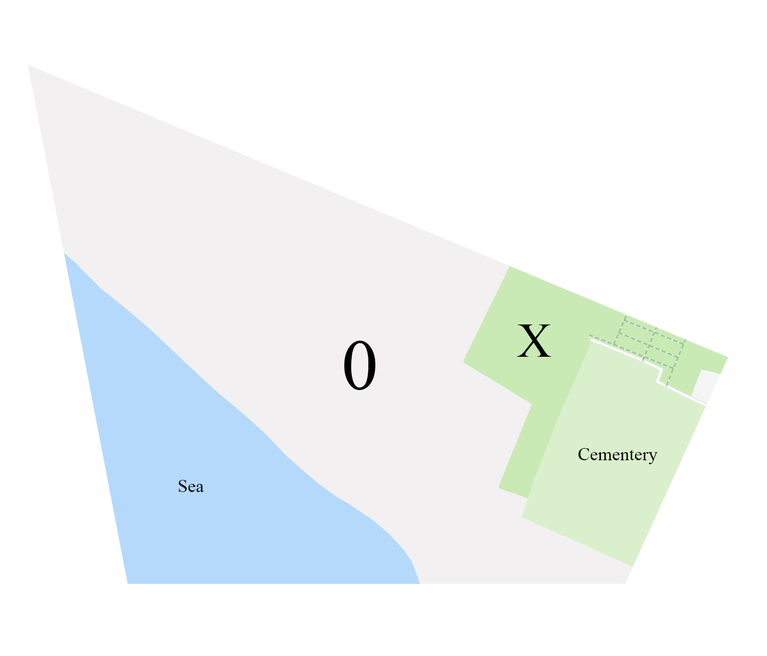

X Space for official celebration

0 Space for alternative celebration (In google maps, this place is blank. Nor is it indicated by any name)

SPACE FOR CELEBRATION

The idea of an International Paella Competition was originally conceived by a group of friends from Algorta (Bizkaia, Basque Country). The event has been held every year since 1956 on 25 July, the Day of Saint James, although the date tends to vary.

The first paellas, as they are known, were held in the proximity of the Azkorri football field next to the dilapidated fence surrounding the pine forest of the Viuda Del Marqués de Rivas near Goienetxe (Getxo, Basque Country).

In 1958, the paellas were moved from the fields of Azkorri to their current site in Aixerrota.

While the feast takes place in the area closest to the graveyard, groups of young people from Algorta and the surrounding areas set up an alternative, daytime celebration on the other side of the brambled hedges separating the fields of Aixerrota. As these groups have no space of their own and are not provided with any kind of shelter by the council, they build their own stands over the months of June and July and extend their territory to the edges of the pine forest near the cliffs.

During the time it takes to set up the space, a celebration in itself, the place is set apart from the space it occupies on other days of the year, transforming into a self-sufficient unit where time is suspended, where a rupture in common perception takes place, and where all kinds of affects are intensified. Thus, it creates “a limited fragment of time, in which this work tries to steal from time itself a few instants of pure joy” [1].

Experiencing this happening interrupts the walker’s or runner’s self-absorption and perception. In my particular case, carrying this across into art as in Un Atletismo Afectivo compelled me to rediscover the space I live in: my domestic space and the landscape I experience when I run; what is inside and outside but always very close to the body. The feeling of place allows me to return to this space and to the artistic experience linked to it through memory and affect, as well as through physical characteristics and geographic coordinates. I am hereby able to recreate aesthetic experience by means of formal aspects such as touch, light, colour, sound, and action.

Trenza is constructed around a series of chronologically-ordered actions that form the basis for added materials (in order to emphasize the process of setting up the event, no images of the actual celebration are shown). The added material consists of extracts of a voice-over by David Attenborough from the documentary Bowerbirds: The art of seduction [2] which shows male bowerbirds building the bower for their courtship. It also includes sequences of my own artistic process, with a strong emphasis on the present, immediacy, and closeness.

ACTIONS

Choosing and staking out the space. The space given to non-official stands runs from the brambles in the middle of the fields to the pine forest behind them. The first groups to arrive choose the best, level spaces which can most easily be enlarged. The pine area and spaces on the edges are chosen last.

Spaces are marked out with tape or ropes attached to wooden stakes indicating the corners of each territory. Each stand is normally built onto the next one, so that two of the walls of each space are shared with neighbouring groups.

Upkeep. Group members normally share the task of guarding the space to ensure that the plot is not entirely taken over and that nothing is stolen. Sometimes, it needs to be staked out again. This process tends to go on until the building of the stand is well under way. One of the ways of showing that a space already belongs to a group is by cutting the grass. This is normally done once the space has been staked out, and again a few times before the day of the celebration.

Building up. Building the stand is the hardest task when setting up the space. The simplest structure is typically a plastic gazebo, which comes with its own instructions. Some of these have plastic walls, others not. Sometimes grid-type walls are built using rope and ferns. Often the shelter is made out of building pallets, wooden rafters , and cork boarding. Once the main structure is built, furniture is brought in. The larger groups normally have a table and wooden benches. Sunshades are a regular feature. Mats are often used as beds. The stalls are very often decorated with flags, flowers, and even painted rafters or corner posts.

Buying provisions for the celebration. Food and drink are normally purchased a few days before the event. Quite often, stocks of rice and beer in the nearby supermarkets are exhausted. One unusual feature of this feast is that friends (and often strangers) are invited for drinks when they pass by the stands.

Getting the music ready. Music is an essential part of the celebration, particularly for large groups of young people. Some of them test out the generators and loudspeakers and this often gives rise to festive breaks in the preparations.

Sexual selection, as analyzed by Elizabeth Grosz (2008), succesfully calls into question the neo-Darwinian doctrine that chance mutation is the only source of life´s variation, loosening morphogenesis -the genesis of forms of life- from the grip of blind chance. It also calls into question the associated doctrine that the only principle of selection operative in evolution is adaptation to external circumstance (Grosz 2011, pt. 3, ch. 8). In the arena of animal courtship, selection bears directly on qualities of lived experience. The aim is at creativity, rather than adaptive conformity to the constraints of given circumstance. Sexual selection expresses an inventive animal exuberance attaching to qualities of life, with no direct use-value or survival-value. As Darwin himself pointed out (1871, 63-64), the excesses of sexual selection can only be described as an expressión of a "sense of beauty".

Brian Massumi, What animals teach us about politics [3]

THE NEED TO BOND

This investigation stems from an intuitive idea that there is a need for attachment [4] in the activities of any being partaking in life, nature, and art, and that this need involves encountering others in such a way that suspends self-absorption. In bonding, there is an aspiration to subjective destitution which gives rise to a relationship in which subjects are renewed, become something other than what they believe themselves to be, and remain open to becoming. A desire arises to do something with others. The “doing” or “making” subject, who operates from her/his distinct condition, wishes to cause the other to feel, “wants to involve others in an induced, displaced bond” [5].

An example of this would be the spaces built by male bowerbirds, which they use as a dance floor for courting the female. These architectural spaces can be up to a metre high, thirty times the size of the bird. There is often a path leading to the space, which the male bird adorns with treasures such as flowers, worms, feathers, stones, pieces of glass, and other objects, the arrangement of which is by no means random. Some bowerbirds paint the walls of the bower red with a mixture of ink and saliva. Others prefer blue. Male bowerbirds are also highly competitive, often stealing other males’ objects or destroying their spaces.

It would be hard to explain this complex work, which is continuously evolving and expanding, simply as a response that has evolved out of a relationship of need or satisfaction. As Massumi says about Grosz, an excess happens, a going beyond, an intensity related to the idea of beauty: “The capacity to produce unexpected outcomes that are not related in linear fashion to discrete, isolatable inputs is an essential aspect of instinct. It must be acknowledged that instinctual movements are animated by tendency to surpass given forms, that they are moved by an impetus toward creativity” [6].

In instinctive movements such as these, there is also an element of spontaneous improvisation bound to qualitative variations. Similar behaviours can be seen in the cuckoo nestling who, once it has invaded the nest of a female of another species, is able to make her feed and protect it. This evokes a passionate response. Just like in the bowerbird, a mechanical impulse turns into a passionate drive: “Instinct bears witness to a self-driving of life’s creative movement: to a self-expressive autonomy of vital creativity” [7]. Instinct enables an excess of invention beyond simple conformity within the limited demands of adaptation and death; a type of creativity immanent to the topology of experience that spontaneously responds to the pressures of adaptation. Deleuze and Guattari define this immanent capacity for invention as desire [8].

MAKING A HOME

Perhaps we could say that art begins with animals, or, at least, with an animal such as the bowerbird when it stakes out a territory and makes a home [9].

When a home is built, many organic functions, such as sexuality, procreation, aggressiveness, and feeding, become transformed. The building of a territory implies the emergence of purely sensitive qualities [10]. This emergence, which, it could be claimed, relates directly to the artistic process, is present in the paella feast just as it is in the male bowerbird’s building of the bower for his courtship performance-action-song. The protocol (defining the space, defending it, building vertically, decorating) has an almost literal correspondence with the preparations for the paella celebration.

In the architecture of the spaces, the stands for the celebration require walls, a roof, an entrance, and space for a fire. But they can also include a pit latrine in the most hidden part of the terrain, spaces for eating, a dance floor, a bar, or a tower.

Participants spend around two months working on a fragile, ephemeral event which will be over in a day. In the time leading up to it, they dispose and are predisposed. They build a space, a context, one stage at a time, until a home is made. “All celebrations require long, careful preparation. […] A party requires the solemnity of the wait and pre-existence” [11].

Just as the bowerbird drops the leaves it cuts from a tree every morning and turns their inner, lighter side outwards to contrast with the earth – making a space for performing that shows off the yellow inside of the feathers under its beak – the members of the paella celebration choose the best, biggest, flattest space, stake it out, defend it, build it upwards, signal it with flags, and pay careful attention to details like decoration, using paint, flowers, plants, and music, food and drink.

It is an abundance of joy that gives rise to this celebration, which lasts for a single day and ends the same night.

The transcribed text in this sequence was published in Un Atletismo Afectivo. Its translation can be found in the section UAA

ESOTERIC GYMNASTICS

Trenza includes tutorial-type texts first used in the book Un Atletismo Afectivo and the work process shown in it.

Many of the sequences in the audiovisual piece were filmed during the design and construction of the floor installation Gimnasio Esotérico (Esoteric Gymnastics), which was exhibited in summer 2016 at Bilbaoarte Foundation (Bilbao). The making of this piece forms part of the film. Its structure is inspired by the observation of the bowerbird’s folly and the stands at the paella feast.

The relationships that arise between different objects in Gimnasio Esotérico originated in the poster Ruler Manifest, also reproduced in Un Atletismo Afectivo. This is a visual guide in which elements are linked through actions designated by some of the geometrical forms used to build flow diagrams. Flow diagrams are representations of an algorithm or process and show steps towards the resolution of a problem.

In Gimnasio Esotérico there is no problem to be solved. The process of setting up the piece outlines only one possibility for creating order. Different elements that I have been using for some time are arranged on a grid at different levels of representation or presentation. The elements can be thought of as objects or tools and include different media such as fabric, photography and digital montage.

Flowers, coffee grains, pencils, or particular geometric shapes are common objects I have formed a relationship of presence and affect with, which has led me to play with words and materials.

BODIES

The desire for love and erotic passion in creation are also part of building the festive space. The desire for love is a desire for a sensibility that opens being up to external interference. In this opening up, the body – each person’s body in relation to other bodies – plays a primary role. “The work of art is another kind of body in itself. There is no artwork without embodiment. The artwork is a physical body, altered by the maker’s embodiment and also by the viewer’s” [12]. This leads to an idea of the knowledge of art as a bodily knowledge; a proxemic space “in which the body knows itself and savours itself” [13]. The manual work of the artist also entails physical embodiment in her work with her materials.

This statement might be illuminated by Spinoza’s idea of the body as having a capacity for affecting and being affected: a body which becomes defined by the capacities it presents through time [14]. The desiring body, the body that constructs, the feeling body, the suffering body, the body-work that is altered by the maker and the viewer. In this interlocution we are never alone. From this perspective, affect is a way of connecting with others and other situations, and a force that allows us to participate in processes larger than ourselves [15]. Seen from the point of view of its potential and ability to make things happen, affect is a bodily movement.

The process of art, like the process of setting up the festive space or the bowerbird’s process of building its bower, implies a “hypothetical sympathy” [16] which means that the intuition can explore through making, expanding its field of relationships and opening up space for the appearance of minor gestures. Intuition adds to instinct the embodied nature of the present situation.

From the observation and admiration of a natural, instinctive creative process, Trenza attempts to connect the experience and setting up of a celebration with the making of art, creating relationships through the reading and writing of texts, repeated or exceptional lived experiences, objects at the bottom of my desk or thrown onto my studio floor, the sound of the weeding, or the noise in the patio at three in the afternoon. This exposition poses a question about other possible arrangements of some of this material, the production of different layers of sound, image and words: Might a different way of articulating these processes using the tools offered by this platform give rise to a new way of making? Or, to put it differently, what can a process do?

Coffee Connector, Flower Fluid, Be Bird, Floor Visual Display

The geometric forms are cut out of foam rubber, a soft but resilient material that protects valued or new things. Here, it demands to be present, on flowers; it expands, or builds landscapes or still lives, depending on how you look at it. A relationship, a bond, is built through coffee grains and pencils. They are vulnerable forms of existence that propose everyday tensions and harmonies and give rise to new forms of action.

[1] Jeanne Hersch, El ser y la forma (Buenos Aires: Paidós, 1969), p. 72

[2] Bowerbirds: The art of seduction by David Attenborough (Lifestory BBC, 2000)

[3] Brian Massumi, What animals teach us about politics (USA: Duke University Press, 2014), p. 2

[4] Juan Luis Moraza, "El deseo del artista" in Deseo. Textos y Conferencias (Madrid: Colegio de Psicoanálisis), p. 14

[5] Ibid.

[6] Brian Massumi, What animals teach us about politics (USA: Duke University Press, 2014), pp. 16-17

[7] Ibid. p. 18

[8] Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, Anti-Oedipus (Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press, 1983), p. 25

[9] Gilles Deleuze, Félix Guattari, ¿Qué es la filosofía? (Madrid: Editorial Anagrama, 1993), pp. 185-186

[10] Ibid.

[11] Jeanne Hersch, El ser y la forma (Buenos Aires: Paidós, 1969), p. 65

[12] Juan Luis Moraza, "El deseo del artista" in Deseo. Textos y Conferencias (Madrid: Colegio de Psicoanálisis, 2011), pp. 1-16 (p. 14)

[13] Ibid.

[14] Baruch Spinoza, Ética (Madrid: Alianza Editorial, 2013), p. 209

[15] Brian Massumi, Politics of Affect (UK: Polity Press, 2017), p. 6

[16] Erin Manning, The minor gesture (USA: Duke University Press, 2016), p. 38

[17] Henri Bergson, The creative mind (New York: Dover, 2007), p. 135