From Manuscript to Performance

The Artistic and Personal Impact of a Premiere

Manuela P. Espinosa Núñez

Supervised by Emlyn Stam

Fontys Academy of the Arts

Master in Music

Index

-

Cantillana: A Place of Tradiction That Shaped Us

-

Analysis of the piece

-

Information compilation

-

Interview with the composer

-

Documentation

5.1. Perfectionism

5.2. Score-related difficulties

5.3. Practice sessions

5.4. Applied methodology

-

Premiere video

-

Perspectives

7.1. Reviews

7.2. Composer’s

7.3. Survey for audience

Conclusion

Bibliography

Appendix A: Analized score

Abstract

In this thesis, I share my research process for premiering a work by composer Antonio Paniagua in a chamber music series held annually in his honor. The piece was composed in a musical style that I do not master as a performer, and there were no existing references on how it should sound.

The central question guiding my research was: How do I interpret this work without prior references? Throughout the process, I encountered numerous mistakes and made decisions that were not entirely successful, forcing me to constantly rethink my approach. While the final result was satisfactory, it was not exactly what I had anticipated.

For this reason, I share my experience and insights in this thesis, hoping that those facing similar challenges can learn from my journey and avoid the mistakes I made.

Introduction

Painting on a blank canvas is terrifying, but trusting the process and allowing yourself to be vulnerable as a performer is even more daunting.

I was honored to be invited to premiere a musical piece at the annual Antonio Paniagua Chamber Music Festival, held in my hometown. Participating in this festival had been a long-standing aspiration of mine, making this opportunity incredibly meaningful. From the very beginning, I felt both deeply flattered and determined to deliver a performance that would leave a lasting artistic mark on the cultural expressions of my community. Knowing the extraordinary talent and artistry of the other performers participating in the festival, I was driven to meet the high standards they set and to rise to the occasion.

The main problem I had to face was premiering a piece written in a style unfamiliar to me, without any references. The piece itself came with a unique set of challenges. I knew it had been attempted for a previous edition of the festival but was ultimately deemed too difficult to perform. Compounding the challenge, the composition was handwritten, leaving me without any prior audio references to guide my interpretation. Additionally, some of the information I initially received about the work turned out to be inaccurate. For instance, I was told the piece lasted 40 minutes and contained numerous extended techniques, which I later discovered was not entirely true. Despite these discrepancies, I approached the situation as an ambitious artistic challenge. Consequently, to work on my main challenge, I focused on the following questions: what resources do I have to work with, how should I plan my approach, and what questions arise from this process? The first sub-question was limited to the written musical source—the score—and the rehearsal and concert dates scheduled a few months ahead. For the planning stage, I devised different possibilities, as will be explained later. Finally, the questions that emerged regarding the style, the composer, and the piece itself will hopefully be answered throughout this research study.

In this work, I will conduct a detailed analysis of the musical piece itself, exploring its structure, style, and technical demands, as well as my interpretative process and artistic decisions throughout its preparation. By delving into the composition’s unique characteristics and the challenges it presented, I aim to provide insights into the work’s artistic significance and to document my personal approach to bringing it to life.

Looking back while preparing this research, I became aware of a common factor throughout the entire process. To summarize it and ensure it is easily understood, I have decided to name it Perfectionism, and it will be explained in detail. Broadly speaking, it led to such a high level of self-demand that it blocked any progress that might have emerged. By requiring perfection and guaranteed success, any option to move forward was overshadowed by an overwhelming fear of failure.

To approach the interpretation of the unpublished work, I adopted an exploratory and inductive methodology, relying on progressive discovery and learning through practice. Without prior references, I advanced in studying the piece by directly experimenting with the score, identifying challenges, and formulating questions about the composer’s style and intentions. As I delved deeper into the work, I took notes on aspects that raised uncertainty and structured inquiries for the composer, turning our interaction into a key source of information. This process, largely carried out “in the dark,” allowed me to develop an interpretative approach based on constant adaptation, exploring different possibilities and refining my perspective as I gained deeper understanding of the piece. Thus, my artistic research was not only a technical exercise but also a creative immersion that combined trial and error with continuous reflection.

I decided to focus my research work on this topic not only to share my experience with fellow performers who may face similar situations but also to honor and promote the artistic work of the composer, a highly skilled musician and fellow native of my hometown. This research serves as a way to enrich his composition, to document and share my personal journey, and to further the artistic culture of my beloved Cantillana.

Throughout this work, I will use certain terms that I believe should be clarified. When I refer to my artistic decision, I mean the choices I make as a performer regarding the piece. These include interpretative decisions such as prioritizing one element over another, selecting phrasing, considering how to assemble and study the work, and, ultimately, interpretative factors that go beyond the indications in the score, for which the composer provides no specific instructions.

The same applies to the term approach, which I will use to describe my stance toward the piece, shaped by the interpretative decisions I have made. Experiences can be defined as the events I went through during the entire process of studying and internalizing the Sonata, highlighting challenges as those aspects that presented the greatest difficulties.

To put it briefly, this thesis documents the preparation process for the premiere of an unpublished work, tackling the challenge of interpreting a composition without prior references. It explores the methods used, the obstacles encountered, and the decisions made, aiming to provide useful tools for other performers and contribute to the appreciation of the composer’s work.

Literature review

This section will discuss some of the bibliographic sources I have consulted throughout the development of this research project.

As previously mentioned, the information I initially received about the piece was inaccurate, and a considerable amount of time passed before I finally obtained the score and could verify it. As a result, I first sought information in an area that later proved to be irrelevant to these specific circumstances. Nonetheless, information remains a valuable source of knowledge that deserves recognition, so it will be included in the bibliography section. Even if not directly applicable, it has undoubtedly contributed in some way to the completion of this work.

For this section, I have selected sources that were particularly relevant to two key aspects of my research: optimizing practice sessions and understanding the relationship with the composer. Below, I present my analysis and evaluation of the two most useful sources.

Clarinet Handbook (University of North Texas College of Music, 2011–2012)

This handbook [1], published by the University of North Texas College of Music, provides a comprehensive guide to clarinet performance, covering technical aspects, practice recommendations, and stylistic approaches.

Its usefulness has been instrumental in structuring my practice sessions—both those dedicated specifically to this piece and those focused on broader technique development. In the section “Productive Practicing”, the manual outlines essential tools every musician should have at hand during their study sessions, alongside general recommendations that helped me optimize and organize my practice time efficiently.

This source reads like an instruction manual for maximizing practice sessions, packed with valuable clarinet-related insights: warm-up exercises, study book suggestions, orchestral excerpt selections, and pedagogical articles—particularly those on reed selection and adjustment.

Simply put, this handbook was exactly what I was looking for, containing even more useful content than expected. Compared to similar sources, such as Hadcock’s [2] manual, I find it more user-friendly due to its practical approach. The Working Clarinetist, unlike this source, presents a series of rules and objectives to achieve. Its first section—one I had previously searched for without success—establishes fundamental clarinet principles, outlining best practices for tone production and articulation. Hadcock focuses on intonation, rhythm, articulation, tongue positioning, and adjustments for commercial reeds or custom reed-making. However, Clarinet Handbook provides applied exercises designed to help achieve these goals.

Additionally, the handbook offers a problem-solving section, guiding musicians through troubleshooting common issues encountered during practice—for instance, handling unwanted overtones, identifying reed inconsistencies, and refining performance technique through concrete examples.

Ultimately, both sources have proven valuable, albeit with differing strengths. The University of North Texas College of Music Handbook strikes me as an invaluable resource that should be easily accessible to musicians of all levels. To accommodate varying skill levels, it provides exercises of progressive difficulty and transpositions in multiple keys. In my specific case, the piece I worked on lacked a defined tonal center, but its interval exercises were still highly beneficial.

For its versatility and practical depth, I consider this handbook an essential resource. However, I am certain that the first section of The Working Clarinetist, dedicated to guided orchestral solo practice, will be incredibly useful when I tackle related challenges in the future.

SHADOWS: Piece for Clarinet and Live Electronic (Fernández Caballero, 2022)

This research project, developed by my esteemed colleague and friend M. Victoria Fernández Caballero [3] in collaboration with Spanish composer Manuel Emilio Marí Altozano, was part of her Master of Musical Performance degree at Kungliga Musikhögskolan. The piece explores the interplay between the clarinet and live electronics, offering an innovative approach to contemporary performance. Her technical analysis and artistic development provided valuable insight into the expressive potential of the clarinet when combined with electronic media.

I reached out to Victoria for recommendations on sources relevant to my situation, and she kindly shared her work with me. I was unaware that she had engaged in a process so similar to mine, which led me to reflect on how little I knew about the artistic and professional journeys of my peers. In certain circles, these “details” tend to be overlooked, revealing a gap in awareness about the creative endeavors unfolding around us.

Upon reviewing her work, I discovered an incredibly detailed and extensive resource documenting her experience. Her project centered on the preparation of a concert designed to enhance the audience’s experience, featuring two solo clarinet pieces by Marí Altozano, both deeply embedded in contemporary musical language. Initially, I had received inaccurate information suggesting that Paniagua’s Sonata shared a similar compositional style, so I was delighted to have access to Victoria’s insights. However, once I realized this was not the case, my engagement with her research became more of an intellectual curiosity than a directly applicable reference.

Later in this paper, I will discuss Antonio Paniagua’s perspective on audience reception, highlighting the stark contrast between his approach and the concert Victoria prepared. Still, despite the differences, her collaboration process with the composer proved highly inspirational. It reinforced the importance of communication in these artistic exchanges, and her numerous examples of composer-performer collaborations made me appreciate how fortunate I was to be able to ask questions, propose ideas, and seek guidance from Paniagua. Ultimately, Victoria’s work and her personal recommendations played a crucial role in motivating me to cultivate a closer relationship with Paniagua throughout the preparation of his piece.

I also found the structure of her work inspiring. Victoria thoroughly discusses each piece she tackled, the challenges she faced, and the solutions she devised. Moreover, her decision to include the score as an appendix to her project served as another valuable reference point.

Other Sources

Additional references were useful at specific points and deserve mention in this section. Cook’s article [4] provides extensive insight into the historical relationships between composers and performers, as do Smalley’s work [5] and Vanmaele’s thesis [6]. Inspired by the bibliography of Alexandra Pinheiro de Araújo’s research work [7], a former Fontys Academy of the Arts student, I consulted the same sources due to the similarity between our research topics. I am deeply grateful for Alexandra’s willingness to collaborate on this work by sharing her thesis, which proved to be an invaluable source.

Cook’s article was somewhat challenging to read, as it seemed to shift perspectives on composer-performer relationships constantly. Just as it convinced me of one position, it would immediately highlight its flaws, creating a cycle of contradictions. Smalley’s work follows a similar pattern but is presented in more accessible language, making it easier to grasp.

One common difficulty with most sources—except for the two discussed in previous sections—was comprehension. I believe I speak for many fellow musicians when I say that those of us who do not regularly rely on academic sources often struggle to fully grasp the intended message. We would appreciate clearer, more concise, and straightforward presentations of information rather than dense technical language. In this regard, the chapter summaries in Vanmaele’s thesis were especially helpful. While still specialized, they made it far easier to identify useful information without having to sift through dozens of pages.

Vanmaele emphasizes the immense value of the score, treating it as a precious link between composer and performer—an archive of instructions left for future musicians. However, I personally found Paniagua’s direct input to be a more human, practical, and productive source of information than the score itself. Vanmaele also discusses the confusion that arises for students when encountering contradictory sources, but fortunately, this was not a challenge in my research since I had direct access to the primary source of information. This source also served as a guide for defining concepts that were not entirely clear, thanks to the glossary provided at the beginning.

Findings

1. Cantillana: A Place That Shaped Us

Both Antonio and I share the same homeland. Although, as I will explain later, he spent much of his life in the center of Seville, the culture of Cantillana had a profound influence on our lives. We were born, raised, and lived immersed in its traditions and customs. This chapter aims to provide context for a small part of our roots and identity, showcasing the culture that shaped our artistic development into what it is today.

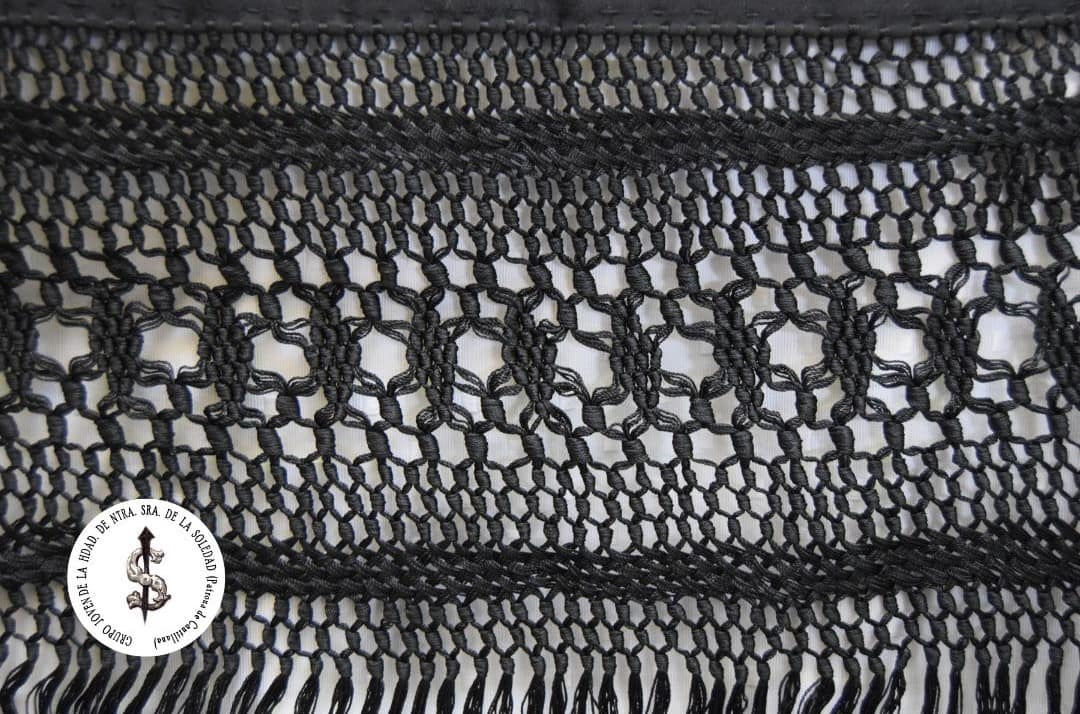

Latticework (Enrejado)

A mantón is a silk piece, either square or triangular, richly decorated in vibrant colors with natural motifs such as flowers, birds, or abstract patterns, and finished with fringes. I dare say that the image of an Andalusian woman is strongly associated with this accessory, just like flamenco. Worn over the shoulders, it is a highly valuable handcrafted piece, symbolizing elegance and cultural identity.

Beyond the immeasurable value of its hand-embroidered designs, the enrejado of the fringes adds another layer of craftsmanship. This intricate knotting technique, which finishes the edges of the mantón, originated in Cantillana, a tradition of which we are deeply proud. There are numerous variations of enrejado, but all follow an artisanal process that makes each piece unique. Factors such as the direction of the knots, the number of silk strands, and their precise placement contribute to an unparalleled craft, one that provides livelihood to many women in Cantillana.

Historically, women in Cantillana had little access to formal education. In Andalucía, poverty was widespread, with most people working the land or serving the few wealthy landowners. Large families were common, as more children meant more workers contributing wages. However, this also led to higher expenses for food and clothing, forcing families to cut costs elsewhere. If a family could only afford to educate one child, priority was always given to the eldest son. As a result, nearly all women remained illiterate, with the best-case scenario being completing primary school. Later in life, they were expected to become homemakers while their husbands provided financially.

However, the mantón embroidery and, particularly, enrejado, offered women a socially accepted craft that also granted them a degree of financial independence. Using a foam pad placed against a chair’s backrest, they engaged in the meticulous process of weaving silk strands and knotting them into the enrejado design. In doing so, they not only contributed to Cantillana’s cultural heritage but also secured savings and elevated their household’s economic standing.

Today, it is common to see women taking their chairs out to patios or balconies or forming small groups of neighbors and friends who craft mantones while chatting. It is also frequent to see women collaborate in dressing their daughters for festivals—some sewing flamenco dresses, others working on the mantón, and others crafting accessories. This community-driven tradition turns a challenging circumstance into something social and joyful, woven into the fabric of everyday life in Cantillana.

This year, Cantillana held the First Mantón Fair, an event that showcased the artisanal tradition of enrejado while also serving as a commercial gathering. The fair took place from March 28 to 30, bringing together artisans, designers, and experts in flamenco fashion. Additionally, the House of the Mantón was inaugurated, a cultural center that provides insight into the craftsmanship behind these unique pieces. This event not only highlighted Cantillana’s rich cultural heritage but also reinforced the role of its artisans in flamenco fashion and the local economy.

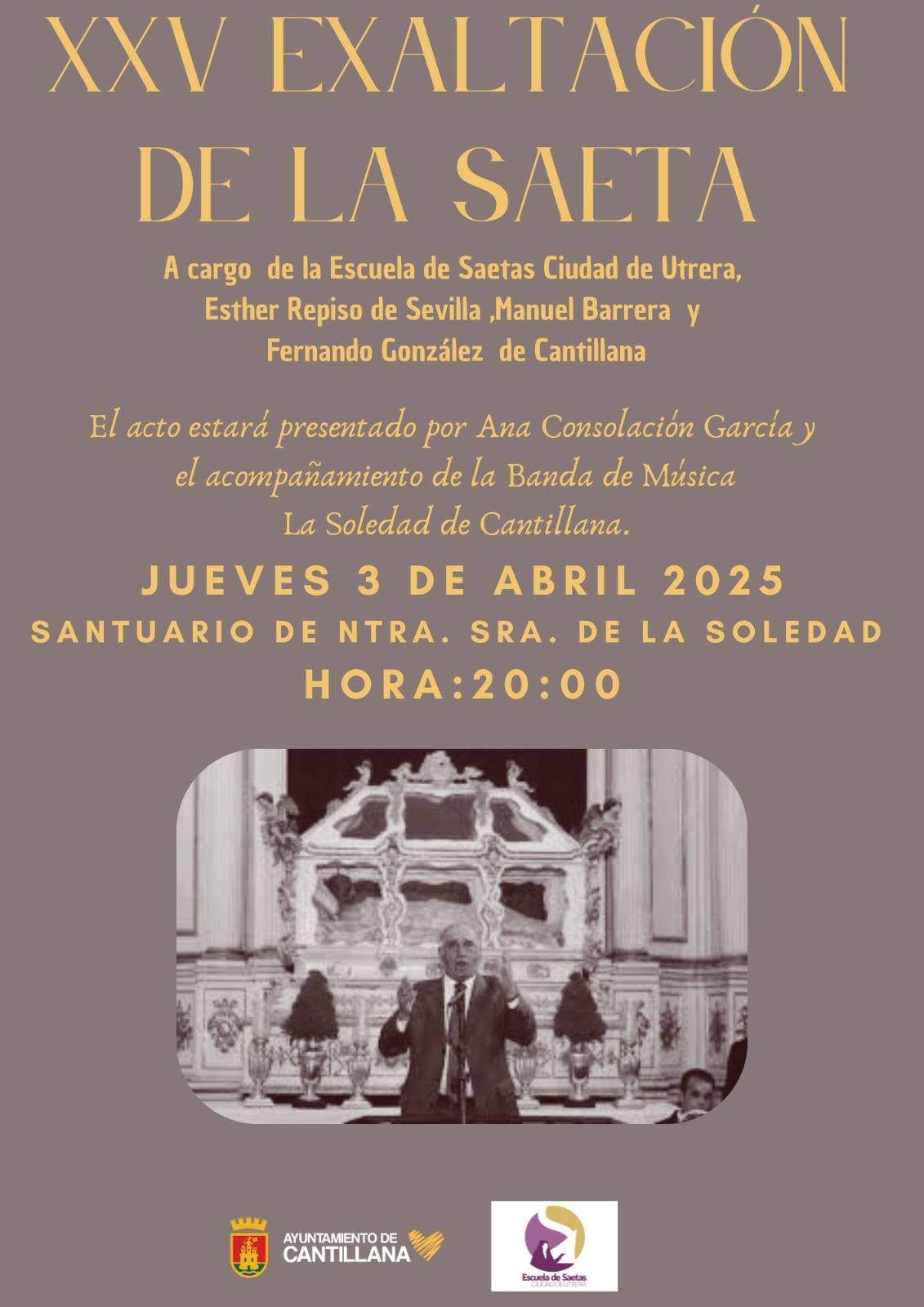

Saeta

Singing a saeta is praying from the heart. This phrase has been repeated countless times in Andalucía, our region. A saeta is a sung prayer with flamenco roots. The saetero or saetera performs this traditional religious chant with great passion, usually during Semana Santa (Holy Week).

In the 19th century, Antonio Machado defined saetas as “little songs whose main purpose is to bring to the people’s memory, especially on Maundy Thursday and Good Friday, certain passages from the Passion and death of Jesus Christ (…) couplets shot like arrows at the hardened hearts of the faithful.”

A saeta is sung as religious images pass by during a Semana Santa procession, often from a low balcony. As the voice begins to be heard and the crowd searches for its source, the capataz (procession leader) instructs the costaleros (bearers) to stop. The saetero may be hired by someone from the cofradía (brotherhood) that owns the image or may be an impromptu devotee wishing to express their faith or artistic talent.

Saetas are common when the images pass through their neighborhoods—sometimes drowned out by environmental noise or the marching band, other times emerging in complete silence. They represent a powerful and deeply moving blend of emotion, art, and devotion.

Currently, the saetas performed are flamenco saetas, resulting from the aflamencamiento (flamenco adaptation) of traditional popular singing [8]. Generally, their melodic line follows a pattern associated with the specific style in which they are sung. Within each style, different regions have their own variations, distinguished by factors such as syllable duration, melismas, and melodic direction.

To foster appreciation for the saeta, enhance emotions during Cuaresma (Lent), and preserve this unique art form, Cantillana holds its annual Exaltation of the Saeta. During this event, an impassioned pregón (proclamation) serves as a guiding thread to introduce the saeteros and saeteras. A balcony railing is placed for them to lean on during their performances, reinforcing the traditional imagery of saeta singing. Additionally, this year marks the beginning of a new initiative—a saeta school aimed at passing down this art form to future generations.

Figure 14. Screenshot of a recording of the event

Recipes

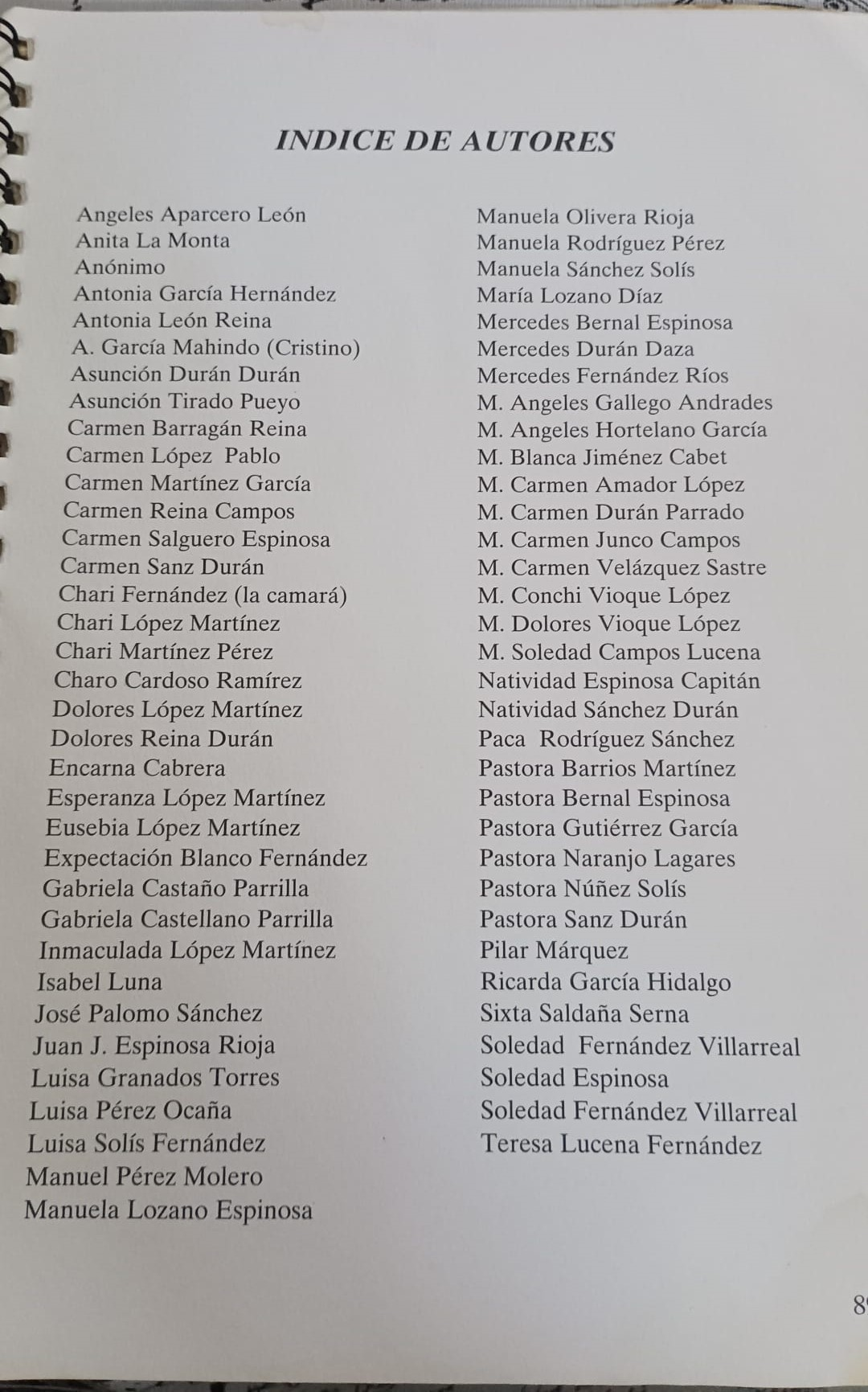

The situation of historical poverty in Andalucía, and consequently in towns like Cantillana, has deep roots stretching back several centuries. During the Reconquista, an agrarian system based on large estates (latifundia) was established, where a small landowning elite controlled vast tracts of land, while the majority of the population lived in precarious conditions as day laborers [9]. This social structure created persistent inequality, which worsened with limited and uneven industrial development during the 19th and 20th centuries, reinforcing a peripheral, dependent economic model with little capacity for wealth redistribution. [10]

Today, Andalucía remains one of the regions with the highest poverty and social exclusion rates in Spain. Structural unemployment, job insecurity, and the rising cost of essential goods continue to affect large sectors of the population [11]. Within this historical and social context, local communities have developed strategies of resistance and adaptation—one of which is popularly known as cocina de aprovechamiento, or “waste-free cooking.”

This form of cooking emerged as a creative and practical response to scarcity. Its goal is to produce the maximum amount of food using minimal or inexpensive ingredients. In Cantillana, this practice has been documented in an unofficial and entirely altruistic recipe collection, compiled by local residents, featuring more than 100 traditional dishes. These recipes use local or easy-to-find ingredients such as alcauciles (artichokes), asparagus, wild thistles (tagarninas), or even stale bread. Thus, cooking becomes not only an act of survival, but also a form of cultural resistance and historical memory passed down through generations.

Ocaña

José Pérez Ocaña was a multifaceted artist, painter, and LGBT rights activist who played a key role in Barcelona’s countercultural scene during Spain’s transition to democracy. Through his performances and artistic expressions, he defied gender and sexuality norms, becoming an icon for both queer activism and art history. He was also a symbol of resistance against Franco’s regime, approaching activism from an anarchist perspective. [12]

Originally from Cantillana, he moved to Barcelona in 1971, where he built his artistic career while working as a decorative painter. His work spanned multiple disciplines, from painting and craftsmanship to provocative public performances. Frequently seen on Las Ramblas, he walked dressed in drag alongside collaborators like Camilo and Nazario, challenging social conventions and paving the way for queer activism in Spain.

His aesthetic was deeply influenced by Andalucía’s popular religiosity, which he reinterpreted through a countercultural lens. This approach was evident in exhibitions such as Un poco de Andalucía (1977) and La Primavera (1982). Ocaña also ventured into cinema, starring in documentaries like Ocaña, retrato intermitente (1978) by Ventura Pons and Ocaña, der Engel, der in der Qual singt (1979) by Gérard Courant, among other films and shorts. [13]

In September 1983, he returned to Cantillana for the Semana de la Juventud. During the celebrations, he created a costume adorned with fireworks, but an accident caused severe burns. Despite initial recovery, his health declined due to pre-existing hepatitis, and he passed away on September 18, 1983. [14]

At the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid, numerous photographs of his works and himself can be seen, reflecting his unique personality. [15]

The Crown Jewel: Our Music Band

**Gabriel Ríos, Founder**

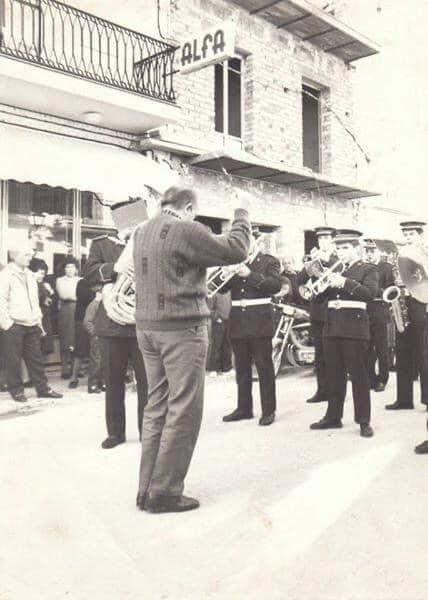

For this section, I had the privilege of speaking with Gabriel Naranjo Ríos, grandson of the founder of La Soledad de Cantillana Music Band and organizer of the VIII Antonio Paniagua Chamber Music Cycle, through which I was able to premiere his Sonata I for clarinet and piano and, consequently, carry out this work.

In the 1960s, Gabriel Ríos founded the band, following an unconventional path. He was self-taught, practicing and studying various instruments such as the trumpet, piano, and accordion. Several family members, including his father and some uncles, as well as friends, had pursued music. According to Gabriel Naranjo’s mother, the band was founded altruistically. One of its objectives, beyond the joy of playing music, was to provide a trade to those interested in learning. At the time, much of the population was illiterate, and acquiring musical knowledge allowed individuals to escape less desirable occupations.

With tireless effort, countless lessons, long hours, and immense dedication, Gabriel Ríos managed to form a band. By the 1980s, it had reached its peak in Semana Santa in Sevilla, accompanying major brotherhoods such as Los Javieres and Las Cigarreras, among others. Being self-taught and living in times of scarcity, his resources were limited. Nevertheless, Gabriel attended conservatory classes regularly, absorbing knowledge that he would later pass on to his fellow musicians, teaching them to read music and perform procession marches—many of which were considered complex even by professional musicians of the time.

Returning to Gabriel Ríos’ altruistic spirit and love for music, his grandson recalls how he would close his carpentry shop between 22:00 and 00:00 and immediately begin teaching music classes to his friends and neighbors. From Gabriel Ríos’ dedication and effort, La Soledad de Cantillana Music Band emerged, led over time by several directors, including José Tinoco, Juan de Dios Espinosa, and Carlos Carvajal—students of Gabriel who carried on his legacy within the group.

**Our generation**

In a dance school in Cantillana that specialized in sevillanas, my teacher suggested to my parents that I had a talent for music. They enrolled me in the music school managed by La Soledad de Cantillana Music Band, where I began attending rehearsals despite not yet mastering my instrument. In this school, former students of Gabriel taught me music and guided me in joining the band, where I developed as a musician for more than 10 years. It was here that I first encountered a composition by Antonio Paniagua, a procession march dedicated to the Virgin of his neighborhood.

From this school emerged what the town recognizes as the next generation of musicians. Looking back, it is touching to see how students of the master later became teachers for new students. What began as a completely altruistic endeavor led to a generation of highly skilled musicians, some of whom I would like to highlight here.

Moisés López, flautist, studied music in Sevilla, earning a Bachelor of Music at Oberlin College, a Graduate Performance Diploma at The Peabody Institute of The Johns Hopkins University, a Master’s Degree at Cleveland Institute of Music, and a Master in Secondary Education and Teaching and Music Research at Universidad Internacional de Valencia. He received an Honorable Mention in the Concerto Competition (2018).

Juanma García, saxophonist, studied music in Sevilla and completed a year at Taller de Músics in Barcelona to prepare for admission exams at the Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya (ESMUC). There, he studied Jazz and Modern Music Performance for four years. Later, he completed a Master in Secondary and High School Education at Universidad Internacional de Valencia and currently works as a music teacher in several schools. Since May 2023, he has conducted La Soledad de Cantillana Music Band.

Gabriel Naranjo, oboist, studied music in Sevilla, earning Honorable Mention. He pursued higher music studies at Musikene in Basque Country and completed a Master in Interpretation at the Royal Conservatory of Brussels. He is currently completing his second master’s degree at the University of Vienna and has traveled across Europe, attending more than ten masterclasses in recent years and performing in numerous orchestras in places such as China, Bordeaux, Basque Country, Italy, and, of course, Spain.

Álvaro García, trumpeter, studied music in Sevilla and completed higher studies at Musikene. He pursued a master’s degree at the Conservatory of Amsterdam and was an academy member of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, where he regularly performs alongside Noord Nederlands Orkest, Belgium National, Brussels Philharmonic, Deutsche Oper, Teatro La Fenice, and Utopia Orchestra.

The traditions and customs of Cantillana provide invaluable context for understanding the origins of both Antonio Paniagua and myself. From the deep-rooted musical heritage passed down through generations to the communal spirit that fosters creativity and cultural preservation, these elements have shaped not only our artistic development but also our identity. The dedication of those before us—self-taught musicians, passionate educators, and devoted artisans—has paved the way for the next generation, ensuring that music and craftsmanship remain integral to our town’s essence. This backdrop of resilience, artistic expression, and collective learning is fundamental in tracing the paths that have brought us to where we are today.

2. Analysis

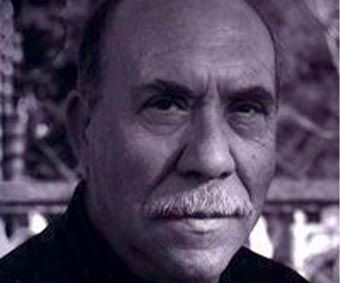

This chapter presents a detailed analysis of the piece on which my work is based, accompanied by a structural outline of each movement. It also includes a brief biography and relevant information about the composer.

Antonio Paniagua Pueyo was born in 1947 in Cantillana, the son of a military father and a homemaker mother. From a very young age, he felt a calling for music, balancing this passion with his studies throughout childhood until he was able to dedicate himself more fully at the age of 17. He then embarked on a prolific musical career, playing in highly popular and renowned groups in both Andalucía and Spain. He was actively involved in the creation of the musical movement known as “Rock Andaluz”, befriending and collaborating with great artists such as Miguel Ríos, Luz Casal, Silvio, and Manolo and Jesús de la Rosa (Alameda and Triana). Antonio performed in hotels across the Canary Islands and in entertainment venues in Salamanca and Sevilla. He even worked aboard cruise ships traveling to America, playing in the onboard orchestras.

At 22, he moved to Madrid, where he played in some of the city’s most prestigious music halls, performing with ensembles such as the Nino Milano Orchestra. In 1980, he began studying double bass, an instrument he would eventually teach professionally. For 12 years, he was the principal double bass player of the Orquesta Bética Filarmónica. He also made incursions into the field of education. He completed his formal music studies, including four years of harmony, two of counterpoint, two of fugue, four years of advanced composition, five years of piano, and two years of instrumentation, ultimately earning a degree in composition with honors.

As a composer, Antonio Paniagua is a member of SGAE (Spanish Society of Authors and Publishers), where he has registered more than 1,500 works. His catalog includes eight processional marches, a chamber music concerto, and over 100 hours of symphonic and chamber music. His works are requested from all over the world, yet, from a humble perspective, he has not yet received the recognition he deserves in his homeland. As the saying goes, “no one is a prophet in their own land”.

Returning to his personal life, Antonio Paniagua married Dolores Daza García. However, their marriage lasted only a few years, as she passed away in 1992. He is the father of three children: Rebeca, Araceli, and Antonio, and grandfather to Alejandro and Jaime. Although now retired, he remains actively engaged in composing. Some of his significant works include Historias del difunto, premiered at the Manuel de Falla Conservatory Auditorium, and Muestrario de silencios, a suite in ten movements for string quartet, based on texts by his friend, journalist, and poet Pepe Morán.

Today, he divides his time between Seville and Cantillana, where he has owned a home since 1997 and where he enjoys reconnecting with friends and family.

The piece Sonata I for Clarinet and Piano, composed by Antonio Paniagua, consists of three movements: Grave-Allegro, Adagio, and Rondo.

The first movement follows a sonata form with a slow introduction led by the piano. The piano introduces motifs and cells that appear throughout the movement, such as chromaticism in the second bar, melodic ideas in bars 8 and 9, and expressive accompaniment, always with a a piacere character. After this introduction, the clarinet begins the exposition by presenting the main theme of section A, which appears twice in different registers. In both instances, the clarinet introduces the theme in its first half, while the piano joins with accompaniment in the second half. Even though the second phrase shortens by one measure, the last bar innovates by introducing a 4/4 time signature, adding an extra beat to the phrase. A brief three-measure bridge leads us to section B, where the character shifts noticeably. The character becomes more rhythmic, with longer figurations and more subdivided phrases, while new lyrical melodic themes emerge. This section, nearly twice as long as the first, adopts a melody-accompanied texture. The contrast between wide intervals (e.g., bars 30, 37, 45, 64) and the chromaticism permeating the movement is particularly notable. The transitional nature of b4 and the apparent rhythmic instability in b5 also stand out, creating an ethereal atmosphere.

In the development, the composer explores and transforms motifs and cells from the exposition, generating new ideas that enrich the piece. Additionally, tempo variations are introduced, such as the rubato in bar 99 and the cadence in phrase d8, maintaining an intimate and chamber-like character consistent with the work.

To conclude, the recapitulation revisits material from the initial exposition but introduces innovations, especially in the bridge to section B and within section B itself. These updates maintain the spirit of the movement, reusing elements like the characteristic bars 151 and 152 while introducing variations such as the piano’s accompaniment arrangement in b9. Finally, the movement concludes with a coda that revisits the “grave” marking, this time incorporating the clarinet. However, instead of offering a conclusive ending, this coda builds tension, culminating in an abrupt finish that leaves a sense of incompleteness and expectation.

The second movement follows a tripartite form with a reexpositive character and is undoubtedly the most intimate, lyrical, and expressive of the entire piece. Throughout the movement, a constant eighth-note pulse provides rhythmic stability while encouraging the performers to delve into and emotionally express the musical phrases. Additionally, frequent changes in meter enhance expressiveness, and recurring 3/4 measures at the end of phrases create brief pauses in the musical discourse.

After a slow introduction similar to the first movement, the opening section presents a main theme played by the clarinet with an “undulating” melodic design that rises and falls proportionally in the first phrase. In the second phrase, this contour intensifies with a more complex melodic line, while a small “valley” between bars 21 and 23 offers contrast, accompanied by similar melodic figures in the piano. A brief four-measure transition links back to the repetition of the main theme.

The second section introduces a stark contrast, with changes in tempo and shorter melodic figures. Here, the character becomes more chamber-like, with a dynamic dialogue between the clarinet and piano. The instruments exchange and develop melodic motifs in a call-and-response format, enriching the musical narrative. For instance, the piano reintroduces the clarinet’s theme, adding new harmonies and subtle variations. Highlights include bars 54 and 55, where a 1/4 measure briefly destabilizes the phrase’s structure, followed by a measure marked tenuto that creates a “false pause” before continuing. Phrase B3 is also noteworthy, as the piano takes the lead with its own melody rather than responding.

The final section begins with a literal restatement of the main theme, reinforcing the sense of recapitulation but introducing new elements in subsequent phrases to enrich the musical narrative. The movement ends with a deceleration in tempo and a texture that underscores the expressive, chamber-like character, preserving the intimacy the composer intended to convey.

The third movement is, without question, the grand finale of this piece, which the composer referred to as “El Miura” during the concert, in reference to the iconic bull. With this metaphor, he congratulated the performers, remarking that they had “killed the Miura”, as a previous attempt to premiere the sonata had failed due to this movement’s interpretive and technical challenges.

This movement follows a rondo form, as its name suggests, alternating a recurring refrain with new phrases to provide unity. Similar to the first movement, after a slow introduction, the clarinet introduces the main theme solo, which the piano responds to with a more intervallic and rhythmic melodic line, contrasting with the clarinet’s cantabile character—a fluid and expressive melodic quality reflecting the composer’s chamber-oriented approach. The second phrase of the refrain, meanwhile, adopts a melody-accompanied texture, creating further contrast with the more conversational nature of the first phrase.

The first of the sections between refrains features two closely related phrases, where the melody transitions from the piano to the clarinet. In this section, the accompaniment shifts fluidly between voices, creating a sense of motion in the score: what begins in the clarinet moves to the piano’s left hand, the left-hand material shifts to the right hand, and the right-hand material is taken up by the clarinet. This continuous exchange adds dynamism and vitality to the instrumental dialogue. Each section concludes with a brief two-measure transition, often marked by a tempo variation.

The refrains also vary, alternating between longer and shorter versions, yet maintaining the same structure in their opening halves. Section C introduces new melodic material and more organic, collaborative textures between the instruments. Key elements include triplets, mordents, and lyrical phrasing, particularly in its opening. The section culminates in a cadential passage where the piano leads first, followed by the clarinet, both ending together as they prepare for a return to a longer refrain. Section D blends elements of section B, such as its consistent eighth-note pulse, with the alternating instrumental dialogue found at the end of section C. This section also includes a brief transition that seems to lead back to the refrain but instead introduces section E.

Section E, marked meno mosso, has a calmer character, creating a false sense of a coda. Similar to section B, its second phrase starts like the first but soon diverges significantly. However, rather than closing the movement here, the composer adds a varied refrain. In this refrain, the second phrase incorporates elements like triplets—reminiscent of section C—reinforcing thematic connections.

Finally, the true coda appears in section F, the shortest section of the movement. Here, the piano takes the lead, seemingly improvising a motive that introduces the next phrase. This motive transitions to the clarinet, and together, they conclude the piece with expressive, lyrical, and chamber-like interplay, emphasizing the cohesive character the composer has sought to highlight throughout the sonata.

The Sonata I for Clarinet and Piano by Antonio Paniagua is a work rich in technical complexity and expressive depth, structured in three movements that explore different musical forms: sonata, tripartite, and rondo.

The first movement combines chromatic and melodic elements with a classic sonata structure and a chamber-like character, culminating in an open, expectant ending. The second movement, highly lyrical and intimate, stands out for its “undulating” melodic design and dynamic dialogue between clarinet and piano, achieving a unique expressive character. Finally, the third movement, referred to as “El Miura” due to its technical challenges, employs a rondo form and offers vibrant and varied instrumental interaction, concluding the piece with an intense and cohesive coda.

Together, the sonata presents an interpretive challenge that allows musicians to explore both their technical and emotional capabilities, while the composer strikes a perfect balance between innovation and musical tradition. A piece well worth listening to attentively!

3. Information compilation

When faced with the situation of premiering a contemporary music piece, my main concern was my lack of knowledge about this style. My training in contemporary music is limited, to the point where I couldn’t precisely define the term or the style. Searching the internet and reading musical treatises weren’t useful, as I realized that no matter how much I read, I wouldn’t truly understand the style until I immersed myself in it: playing, solving problems, and facing challenges.

I then decided to seek advice from colleagues who had already explored this style or something similar since I wasn’t clear about the terminology. I consulted about 20 colleagues, but none of them had any knowledge about contemporary music. Only three of them gave me responses that could be useful.

The first, Carlos, a Master’s student in Classical Music-Clarinet Performance in Maastricht, told me that he didn’t know how to help me because I wasn’t asking a specific question. I only asked him for bibliography and advice since I didn’t yet have the score for the piece I had to premiere. He sent me three books on extended techniques and Peter Hadcock’s masterclasses, which weren’t very useful since the score didn’t contain extended techniques. However, two pieces of advice he gave me in a voice message were valuable. The first was a comment from a professor: “I don’t know of any style of music where the semitone isn’t important.” The second piece of advice was to emphasize and study the use of dissonance or, in the case of several contemporary music composers, noise, used to create tension in the absence of a tonal harmonic relationship between the sounds.

Victoria (Master in Classical Music (orchestra) in Royal College of Music of Stockholm), who also premiered a contemporary piece for solo clarinet in her master’s thesis, sent me her dissertation. I thought it would be immensely useful, but her piece had little to do with mine. Her work included extended techniques, electroacoustics, and the resolution of technical problems to interpret the piece. Although much of her work wasn’t applicable to mine, I was able to observe the structure, writing style, and take inspiration from some points in her index to adapt them to my research.

Finally, Marina (colleague with a keen interest in contemporary music) told me that contemporary music isn’t like classical music, where there is a specific way to play it. The same authors don’t classify themselves within a genre where all their works must be played the same way; rather, there is a vast array of interpretation possibilities and styles. She recommended identifying the piece as much as possible, analyzing the texture to find contrasting passages, and observing the techniques used to achieve this (creating soundscapes, using noise, fast and slow passages…). She also suggested working closely with the composer since I had the opportunity to do so.

Despite the amount of advice from my colleagues, I still felt lost, as I was looking for a clearer action plan. Therefore, I contacted Lars, a professor at Fontys, who, as I had been told, regularly performs contemporary music.

Lars confirmed to me that his work lately was almost exclusively focused on contemporary music, so he was confident he could help me with my problem. I used my budget to book three one-hour lessons with him, leaving some budget reserved in case it was needed later.

The first lesson was conducted via video call, and we used it to get a general idea of the project. I explained the music cycle of the author being celebrated, the history with this piece, and the situation I was in. He gave me some advice on how to prepare the piece, starting with mastering it technically, and we agreed to meet again in a little over a month to do a reading of the piece.

In the second lesson, we read through the piece and discovered that many indications in the score did not match those in the script and clarinet part. This created a problem for continuing the lesson, but we spent much of the time identifying differences and trying to analyze the most appropriate way to interpret them. Finally, I realized that it might be a good idea to ask the composer directly. The rest of the lesson was spent giving musical sense to the passages of the piece. As I had no experience in this type of music, I had limited myself to studying it technically. For the next lesson, we decided to meet in person once the inconsistencies in the scores were corrected and the musical indications he gave me were assimilated to make a general interpretation of the piece (without pianist).

We did just that, with some final indications and recommendations to continue studying the piece. I am very grateful to Lars for his great help in this process, which I consider to have been indispensable.

In summary, I faced significant challenges in premiering a contemporary music piece due to my limited experience in the style. Initial consultations with colleagues provided some valuable insights, but the lessons with Professor Lars were instrumental in overcoming technical obstacles and deepening my understanding of the work. Definitely, resolving score inconsistencies and exploring interpretive possibilities allowed me to approach the piece more creatively and technically, highlighting the importance of fully engaging with the style for personal and professional growth.

4. Interview

In this section, an interview with the author of the musical work is presented, focusing on a variety of topics related to music, his creations, and his artistic process. The conversation delves into key aspects of his approach to composition, his reflections on music as an art form, and his insights on performance and society. To ensure clarity and depth, the interview is organized into five thematic sections that capture the essence of the author’s thoughts and creative journey.

I had planned to conduct a more extensive interview with Antonio on various interesting topics. However, due to our schedules and health conditions, we barely had any time together. In the end, we managed to have a phone conversation, from which I was able to extract and compile a brief interview that I will present in this chapter.

Influences and Learning

Do you have a teacher or someone you look up to regarding composing? Of course. I had the privilege of attending Don Manuel Castillo’s classes as an observer while I was in my third year of harmony and my first year of counterpoint. Even though I hadn’t officially entered the composition program, he treated me as a full student. It was an incredible experience, and we developed a strong friendship.

As a child, Don Antonio Pantión, a renowned Sevillian composer, noticed my musical potential, especially my auditory skills. He encouraged my father to take me to his house, where I began my first steps in music education. That was a huge opportunity for me.

Later, in the 1960s, I became deeply involved in rock music. It was during this period that I realized how important it was to formally study music. This experience allowed me to connect with a wide variety of musical styles.

Who has been the most influential figure in your musical education? Several people have been highly influential, but Antonio Pantión and Manuel Castillo stand out as key figures. Others include Fernando Pérez, who taught me solfège; Paco Ríos, my double bass teacher; José Illescas, my piano teacher; and Luis Ignacio Marín. Each of them played a significant role in shaping my development as a musician.

What pieces, composers, or mentors inspire you? It depends on the era. For example, in the Baroque period, Benedetto Marcello, particularly for oboe works, has been a great influence. For clarinet, I draw a lot of inspiration from Gershwin’s writing, and for oboe, I admire Han de Vries.

What books would you recommend for understanding your music or studying composition? The essential ones are:20th Century Harmony by Vincent Persichetti, Orchestration by Walter Piston, Treatise on Harmony by Zamacois, Musical Theory and Harmony by Enric Herrera and Counterpoint Techniques by Amando Blanquer.

These books are fundamental for understanding musical theory. However, I often find my own concepts of harmony and counterpoint so intricate that no existing treatises fully define them. That’s why I strive to translate these ideas directly into my compositions, reflecting how I personally understand music.

Composition and Style

Talk about your creative process. My creative process has several layers. I often draw inspiration from any sound or melody that catches my attention, like a bird’s song, which might inspire a scale that I later incorporate into my work. When I have an idea, I refine it through an internal filter that reflects my artistic identity.

Improvisation plays a crucial role in sparking new melodies. For example, I’m currently working on a tonal piece for violin and piano, tailored specifically for a friend from the Royal Symphony Orchestra of Seville.

I consider myself a perfectionist, often erasing and revising extensively until I’m fully satisfied with a piece. This pursuit of perfection is more for my own standards than for external approval. I like to think that performers adapt their playing to my compositions. At the same time, I value the freedom of interpretation, as each performance can bring something new to my works.

However, I’m firm about staying true to the original intent of my compositions. This is especially true when dealing with bands of music. Sometimes directors want to make unauthorized changes to my pieces, and I often have to decline these suggestions in order to preserve my vision.

Performance and Practice

How do you think performers should balance personal interpretation with staying true to your compositions? For me, music has a unique and magical quality: its ephemeral nature. Each time a piece is performed, it becomes something unrepeatable—a moment that exists only while it sounds and disappears as soon as it ends. This is what sets music apart from other art forms, like painting, which remains fixed and constant. Music, on the other hand, is an experience, a fleeting instant that lives and dies at the very moment it happens.

I greatly enjoy how each performer is able to bring their own identity and personality to my works. I believe this interaction between my composition and the musician’s individual expression is what makes every performance unique. I’m fascinated by how different people can transform my pieces, enriching them with their own sensitivity and approach. I value that interpretive freedom because it makes my works something alive, something that changes and evolves every time they are played.

However, I am also very clear about the fact that there are limits. While I appreciate the creativity of the performer, I am strict when someone deviates too far from what I have written. For me, my work has an identity that must be respected, and I do not allow changes that alter its essence, such as arbitrary modifications to dynamics or enharmonic substitutions. I can recall many occasions when I had to correct directors who attempted to introduce adjustments they believed would improve the piece but which I considered unnecessary or even harmful to the work as I conceived it.

This balance between allowing artistic freedom and preserving my original vision is something I deeply believe in. Music is ephemeral, yes, but it is also a reflection of my identity as a composer, and I want that to remain intact even as it lives and changes in the hands of different performers. This duality is, for me, what makes music such a special art form.

5. Documentation

In this section, I aim to provide a detailed account of my practice sessions, highlighting the challenges I faced, the potential solutions I identified, and the strategies I employed to address these difficulties. This reflective process is intended to critically evaluate my approach, offering insights into how my methods evolved over time. By documenting this journey, I seek not only to analyze my own progress but also to acknowledge the obstacles that shaped my learning experience.

As I reflect on my mistakes throughout this process, I will make a conscious effort to view them not as sources of shame but as essential and constructive elements of my development. These errors, though challenging, were pivotal in helping me grow both as a musician and as an individual. Given that this was my first encounter with a piece of such complexity and uniqueness, I recognize that a chaotic and unpredictable process was almost inevitable. Unsurprisingly, this proved to be the case.

As my research tutor helped me realize, the presence of negative or unexpected results does not diminish their value. In fact, they are equally significant outcomes in the context of any learning or creative process. These less-than-ideal results are particularly important for fostering personal growth, as they offer valuable lessons for navigating similar challenges in the future. Moreover, documenting and reflecting on these outcomes adds depth and authenticity to this work, offering insights not only for my own development but also for anyone who may read this thesis. By embracing these outcomes as integral to the journey, I am better equipped to refine my methods and contribute meaningfully to the ongoing discourse in this field.

5.1. Perfectionism

Throughout the preparation, I grappled with an overwhelming sense of perfectionism. Now, three months after the concert, I have begun to address this issue in therapy. It is unsettling to reflect and recognize how perfectionism has been one of the most significant challenges in my artistic practice—not only during the preparation of this performance but throughout my entire career. I regret not being more aware of this obstacle earlier, but I am also grateful to have identified it now rather than later. This realization marks an important turning point in my personal and artistic growth.

Understanding the perfectionism I experienced is essential to fully grasp my study process, as it significantly influenced both my methods and my mindset. This deeply ingrained perfectionism shaped how I approached practice, often leading to unrealistic expectations that hindered my progress and disrupted the consistency of my preparation. By analyzing its impact, I can provide valuable insight into the challenges I faced, the inefficiencies it created, and the ways in which it informed my decision-making throughout the journey. Recognizing this aspect is key to interpreting the dynamics of my study process and its outcomes.

Perfectionism caused my motivation to steadily diminish, eventually becoming far inferior to the pressure I felt to premiere this piece. Furthermore, it led me to believe that unless my practice sessions were flawless, they were worthless. This mindset extended to the outcomes of my study; if the results did not meet the impossibly high standards I set for myself, I deemed them inadequate or valueless. This self-imposed pressure, combined with suboptimal preparation strategies, rendered my practice sessions not only inefficient but also inconsistent. The situation was further exacerbated by the unique challenges posed by working on a handwritten composition, which lacked prior references such as recordings or MIDI files due to its premiere status. This absence of external benchmarks intensified the pressure and highlighted the limitations of my preparation methods. Additionally, balancing the study of this piece with the repertoire for my master’s clarinet lessons proved challenging. Despite being informed in advance, I failed to establish a consistent and realistic practice schedule with achievable goals.

Exploring the roots of this deeply ingrained perfectionism is not a simple task, as I am discovering through therapy, and it will undoubtedly require time. However, initial reflections lead me to consider the influence of my conservatory professors, as well as comments from peers and family members. Perhaps the methods of evaluation, communication, and teaching employed by my professors were less than ideal. Having engaged in an in-depth study of pedagogical methodologies for my qualifying exams, I now recognize the shortcomings in the approaches I experienced. I was subjected to disparaging and hurtful remarks that directly linked my worth as a musician and a person to the outcomes of individual lessons. Rather than identifying motivational issues, the response often involved punishment or shame.

I recall the “open classes” at the conservatory, which were presented as an opportunity for students to perform for and receive support from their peers, as well as to prepare for auditions and recitals. However, these sessions devolved into highly critical examinations that few students attended, fearing public embarrassment or the amplified shame of performing before all five clarinet professors. Instead of fostering a sense of mutual growth and support, these sessions became platforms for relentless criticism, where every mistake was scrutinized without consideration for the student’s learning process, efforts, or challenges. These open classes, conducted quarterly, reflected the broader culture of harsh evaluation within the conservatory.

Even outside of the open classes, the routine lessons were similarly discouraging. Mistakes were consistently highlighted, yet no guidance was provided on how to address or resolve them. Instead, the approach was to repeat sections “da capo” until they were executed correctly. Success was often dismissed as a fluke, with statements such as “If it doesn’t work five times in a row, it was just luck.” Even when progress was evident, it was met with comments like “This should have been correct from the very beginning.” This repetitive cycle formed the core of my lessons. Retrospectively, it comes as no surprise that perfectionism has become so deeply rooted in my mindset.

To this already demanding routine, evaluative remarks further compounded the pressure, with comments such as, “You have an 8, but because you are a 10-kind of person, I’ll give you a 4,” or “At this rate, consider yourself in the first year of the sixth course, because it will take you at least two more years to complete,” and even “If you tried harder, you could be excellent, but you settle for less than mediocrity,” and “Don’t you see how much more advanced your peers are? Don’t you realize you are the worst clarinetist in this conservatory?”

Outside the academic environment, extracurricular activities, like playing in my town’s band, provided much-needed enjoyment. However, they were also settings where parents compared their children’s achievements, often leading to comments questioning why my accomplishments did not match or surpass those of my peers. Growing up in a small town where pursuing music was seen as a luxury—or even a waste—added another layer of complexity. In such communities, art is often undervalued, regarded as an impractical pursuit, especially when faced with societal expectations to find a “real” job.

Ultimately, perfectionism rendered the preparation process for this piece unequal, inconsistent, chaotic, and disjointed, significantly affecting my overall experience and underscoring the need for a more supportive and balanced approach to artistic development.

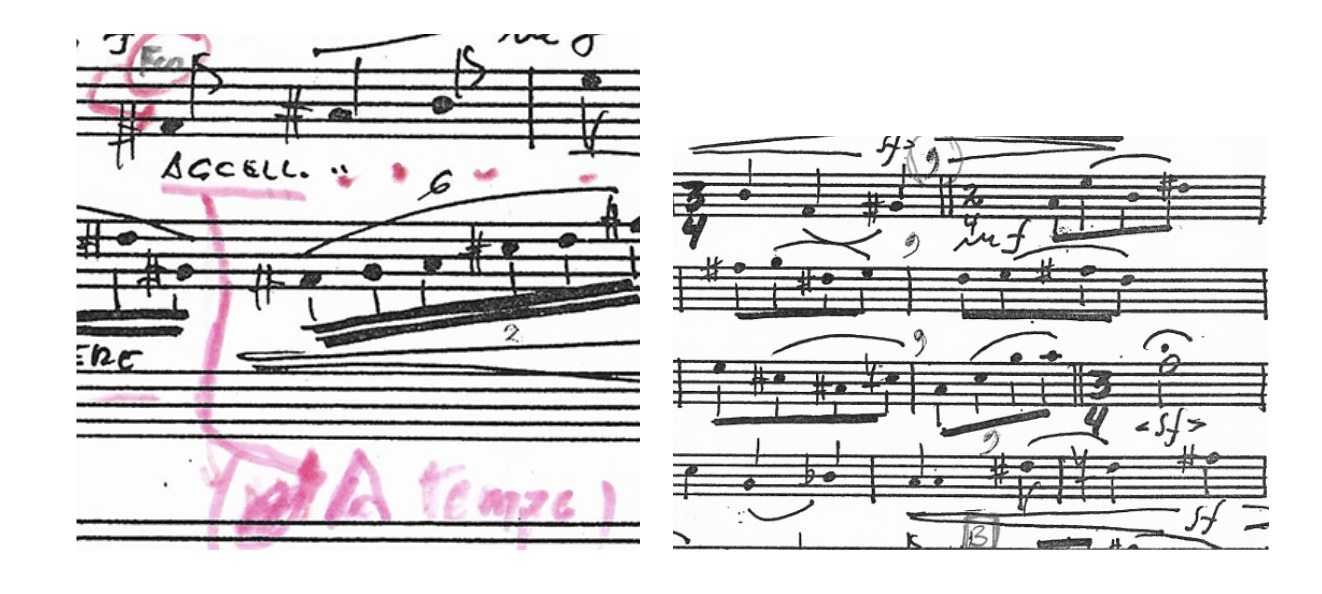

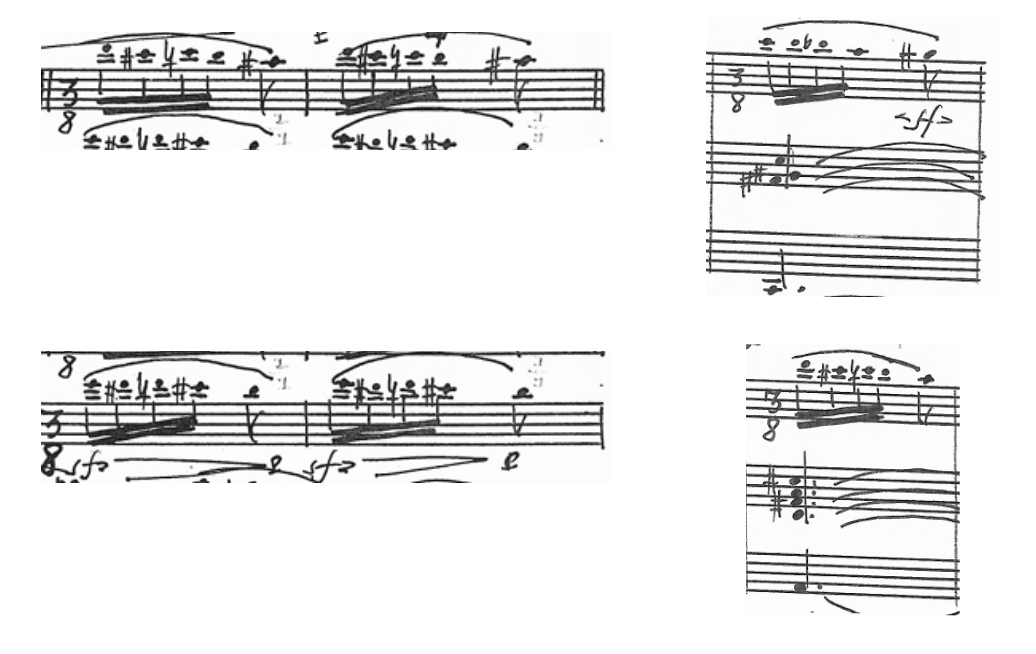

5.2. Score-related difficulties

It took me a long time to recognize these issues, but there is no doubt that the visualization of the scores I received posed a significant obstacle in my study process. As the scores were handwritten, there was confusion regarding some of the notes, which added an additional layer of difficulty. However, the main problem lay in the excessively narrow layout of the scores.

The narrowness of the staves made analysis and interpretation uncomfortable, while the annotations placed between the lines often got confused with those corresponding to the lines above or below. This lack of clarity in the overall design of the score further complicated the understanding of the piece, slowing my progress and making my practice less fluid. Despite these challenges, the process forced me to seek solutions and adjust my approach to move forward.

Adding to this was the insufficient space for making my own annotations, which further complicated my study. Moreover, the score contained other challenges, such as the presence of seemingly handwritten annotations that created confusion and pauses represented with commas, which were unusual and required extra effort to interpret correctly. These limitations not only hindered the clarity of my analysis but also made the practice process less smooth and more challenging than necessary.

The presence of handwritten annotations added an additional layer of uncertainty, as it was unclear whether they came from the composer himself or reflected someone else’s criteria. This lack of clarity led to constant doubts during my study, further complicating the process. In my opinion, external annotations in a score make interpretation more challenging, as they interfere with the original perception of the piece and create unnecessary distractions. This forces the performer to spend additional time analyzing and deciding whether these indications are relevant or should be disregarded, thus slowing progress and reducing the fluency of developing a comprehensive understanding of the score. Moreover, it’s important to note that annotations are deeply personal, reflecting an inherent subjectivity and unique perception of the work by the individual who creates them, which may not align with the vision or needs of the current performer.

To address this problem, I decided to dedicate time to transcribing the score into a digital format and reprinting it. Since I had made this decision, I opted to transcribe the entire piece, including both the piano and clarinet parts, and gift the final result to the composer as a token of appreciation. However, it took me time to recognize that my knowledge of music notation software was not sufficient to achieve a result I considered good enough (once again, perfectionism played an important role). This caused issues with concentration and motivation, as well as frustration for not achieving a result that met my standards. After much time struggling with the program and my own expectations, I finally decided to ask for help. As mentioned earlier, this made a huge difference. Not only did I find a colleague willing to help and teach me to improve my digital skills, but I also achieved an excellent final result. Moreover, during the process, I discovered several errors in the clarinet part I had been studying.

Creating the final digital version of the score was an arduous process that I was able to complete thanks to the help of my estimated colleague Alberto Bellido and his expertise with Finale, the well-known digital music notation software. After transcribing the full score and separating it into individual parts, the process had to be repeated when we realized the software had automatically generated key signatures. Fortunately, I was able to consult Paniagua regarding his preference, and he confirmed that all alterations should be written as accidentals to align better with his style and to make it more convenient for the performers. Following this, and after reviewing the finalized individual parts, I noticed numerous discrepancies compared to the handwritten manuscript I had been studying during the transcription process. This meant embarking on another lengthy process to identify the inconsistencies, annotate them precisely, and consult Paniagua again to determine the final version.

These errors included differing articulations, entire omitted sections, and discrepancies between the clarinet and piano parts regarding dynamics, character indications, and the organization of musical materials. After discussing this with the composer, he explained that he had composed the piece during a moment of inspiration, complete with the smudges, erasures, and corrections typical of such artistic processes. Later, one of his students created a clean copy and separated the parts, which likely introduced these mistakes.

After a long process of reviewing and annotating the differences between the score and the parts, I scheduled a meeting with Antonio to decide on the final version of the piece. I took the opportunity to ask him some questions about whether the piece should include a key signature, how he envisioned certain passages, and how to interpret some tempo indications that were confusing. Antonio, in turn, used the opportunity to make small adjustments to the piece, consulting me to ensure that the changes were consistent with what felt most natural and organic to me as a performer.

Finally, I received valuable guidance from Paniagua, encouraging me to express myself as a performer. He wanted his work to be interpreted differently by each clarinetist and pianist who performed it, aiming to reflect the personal interpretation and artistic judgment of each musician. This gave me a sense of reassurance, as many of my fears revolved around delivering a performance that he might not consider acceptable or correct. His encouragement provided me with the freedom to leave my personal mark on the interpretation, turning the process into a much more liberating and enriching experience.

Before Antonio’s guidance, I was extremely concerned about conveying the exact instructions written in the score. As my colleague Marina told me (and I mentioned earlier in the second chapter), expressiveness in this type of music is generated more through dynamics than through harmonic tension, as in tonal music. For this reason, I sought to interpret the piece exactly as indicated in the score, meticulously measuring the rhythmic cells and ensuring that the dynamic references were perceived with very precise proportions.

After the session addressing score inconsistencies, Antonio made me understand that, although his work is written in an atonal style, it still invites expression. I experienced this firsthand during the first rehearsal with the pianist: if I tried to be overly precise, it simply didn’t work. Truly, after Antonio’s guidance and the rehearsal sessions with Benji (the pianist), I gained a new perception of the work. It feels like a puzzle that only comes together if you approach it with the intent to transmit and express… ultimately, to interpret.

When you infuse your interpretation with musicality and care, you realize that the clarinet and piano parts fit together perfectly, giving meaning to the chamber-like and intimate character of the piece. What initially seemed complex becomes accessible through the music. This is precisely what Paniagua aims to achieve with his work.

5.3. Practice sessions

At the outset, I considered the idea of maintaining a practice journal to track my study process. On paper, the concept seemed promising, and I devoted significant time and effort to testing various formats for these journals. Each iteration included multiple sections, such as warm-ups, questions for the composer, and solutions to various challenges encountered during practice. I spent months debating which sections should be included and how to organize the structure effectively. However, despite my initial enthusiasm, I eventually concluded that the idea was more of a hindrance than a help. The energy and time I invested in planning and revising these journals could have been better spent either directly practicing or even drafting this project itself.

A key obstacle was the impracticality of documenting my thoughts and experiences during the actual practice sessions. For me, maintaining the intense focus required to benefit fully from my practice is already a challenge, and splitting my attention to simultaneously write down notes was simply unmanageable. The act of documenting disrupted my concentration entirely, undermining the effectiveness of the sessions. I found myself caught in a dilemma: I could either write neatly and in detail as I went, which consumed too much time and derailed my focus, or I could jot down rough notes during practice, only to then require additional time and energy—neither of which I often had—to organize and clean them up later.

Ultimately, the attempt to integrate this method into my routine created unnecessary stress and inefficiency. It made clear that while the concept of a practice journal might work for some, it was not the right fit for me, especially given the other demands on my time and the limited resources at my disposal during this project. This realization played an essential role in shaping how I approached my study process and allowed me to identify methods better aligned with my working style and creative needs.

The final and actual process turned out to be far more disorganized than I initially envisioned, something I will elaborate on in detail later. Essentially, my initial practice sessions were focused exclusively on working through the passages from a technical perspective, particularly fingerings. My main goal was to familiarize myself with the piece by attempting to play it from beginning to end at a significantly slower tempo than required for the final performance. This approach was meant to allow my fingers to become accustomed to the notes, gradually internalizing the movements and pathways through repetition over time.

At first, I attempted to analyze the formal structure of the piece to better organize my practice and understand its sections. However, this proved unfeasible. The handwritten nature of the score made it incredibly difficult to read, as previously mentioned, and my limited familiarity with the musical language of the composition compounded the challenge. Additionally, I lacked sufficient time to conduct a thorough analysis, further hindering my ability to grasp the piece as a whole. This difficulty, combined with the effects of my overwhelming perfectionism, rendered understanding the score an almost impossible task—one that I postponed for nearly a year.

Moreover, my attempt to maintain a practice journal—which I initially thought would provide structure to the process—ultimately caused more harm than good. Instead of being a useful tool to document progress, the journal became a source of anxiety and frustration, even making me question the validity of my overall study methods. My practice sessions were inefficient, and the added effort to document them became an excessive burden that exceeded my capacity to manage. This resulted in an accumulation of tasks that left me feeling guilty at the end of each day, further disrupting both my productivity and my ability to rest.

There were also moments of deep frustration when I realized I could not live up to the idealized image of a musician—one who is impeccably organized, highly methodical, and “super aesthetic,” as often portrayed on social media. Those images display a stylized and perfected version of the artistic process, but my reality was far messier and more challenging. At least in my experience, the life of a musician is far more complicated than it might appear online.

This chaotic process highlighted an important truth: perfection in practice is not always achievable. Accepting this reality became a crucial step in learning to navigate the complexities of my artistic journey. It reminded me that embracing imperfections and finding ways to work amidst disorder is a vital part of personal and artistic growth.

5.4. Applied Methodology

Four months before the concert date, I reached a crucial turning point in my process: I finally embraced and accepted the idea that this was not going to be a beautiful, perfect, or even optimal journey. Recognizing this was a moment of clarity, as I realized that the biggest challenges I faced were not merely technical or practical, but mostly emotional and psychological. This understanding allowed me to rethink my approach and take the first steps toward finding a solution.

I came to understand that one of the keys to overcoming my stagnation was something as simple, yet as difficult for me, as asking for help. This act, which may seem natural to many, felt unfamiliar and almost unattainable to me. Accepting that I couldn’t face this challenge alone was a slow process, but in the end, I realized it was essential. Additionally, I acknowledged that I had to let go of the idea of perfection and confront the reality that the concert date was approaching, and I had the responsibility to fulfill my task. Recognizing and acting upon these truths marked a decisive shift not only in how I approached this project but also in my broader learning and growth as a musician.

It’s possible that this methodology has a more technical or professional name within academic contexts, but I chose to call it “warning spots.” This term reflects my intent to approach the process with the same empathy and understanding I once applied to my students as a teacher. For this, I relied on the most basic and effective strategies that I knew had worked for them.

I remembered how I used to tell my students that repeating a lesson from beginning to end countless times just because one small section wasn’t going well was a waste of time and energy. This approach only led to frustration, fatigue with the piece, and in some cases, a loss of motivation to continue practicing. Instead of persisting with this unproductive method, we focused on identifying what I called “warning spots.” These were the specific areas of the lesson where they encountered difficulties during performance. Once these problem areas were identified, we concentrated on them in isolation, enabling a more focused and efficient study. This approach made it possible to find more specific and tailored solutions to each difficulty, optimizing the time and effort invested in practice.

This method not only helped my students progress more effectively but also fostered a more positive relationship with the process of studying and with music itself. Deciding to apply this strategy to myself was not just a practical decision but also an act of self-compassion, a recognition of the importance of being patient and realistic with my own abilities and limitations.

After conducting some research, I discovered that this methodology is referred to as “focused practice” or “segmented practice.” Its approach is centered on identifying specific areas of difficulty and working on them intentionally and methodically. This aligns with the concept of “deliberate practice,” developed by Anders Ericsson, which emphasizes practicing with conscious intent and clear objectives. In the context of music, this methodology helps optimize study time, effectively resolve technical or interpretative challenges, and foster clear and sustainable progress. Moreover, it helps maintain motivation and develop a more positive attitude towards practice by reducing the frustration that more general or repetitive methods can often cause.

Ultimately, I hope to have demonstrated how incredibly enriching this experience has been. After writing this paper, I realize that not everything has been as useless as it seemed in my mind. Looking back, I have come to understand that I have learned a lot. I have managed to recognize and identify the main reason for my stagnation: perfectionism. I faced the challenge of transcribing a score, learning to ask for help. I did arduous work with Antonio to identify and restructure different elements of the piece, achieving deeper insights into it. And last but not least, I learned to guide myself in studying the score with the same care and dedication I would have given to my students, avoiding the consequences of perfectionism and making small progress in dealing with it. The further I advance in this work, the more I recognize and appreciate the opportunity I have been given to develop personally and professionally through this piece.

6. Premiere video