Reflection on Batak Weaving Culture and its Preservation Challenges

The film about Batak weaving in North Sumatra provides an insight into the cultural heritage of one of Indonesia’s most ancient textile traditions. The Batak people, particularly those from the Toba Batak community, have long been recognized for their expertise in weaving, a skill passed down through generations of women. As one of the oldest weaving traditions in the Indonesian archipelago, Batak textiles are not only loved for their aesthetic beauty but also carry cultural and spiritual significance. However, as the film reveals, this tradition faces immense challenges today, primarily due to the forces of colonial history, modern economic shifts, and the decline in transmission of skills across generations.

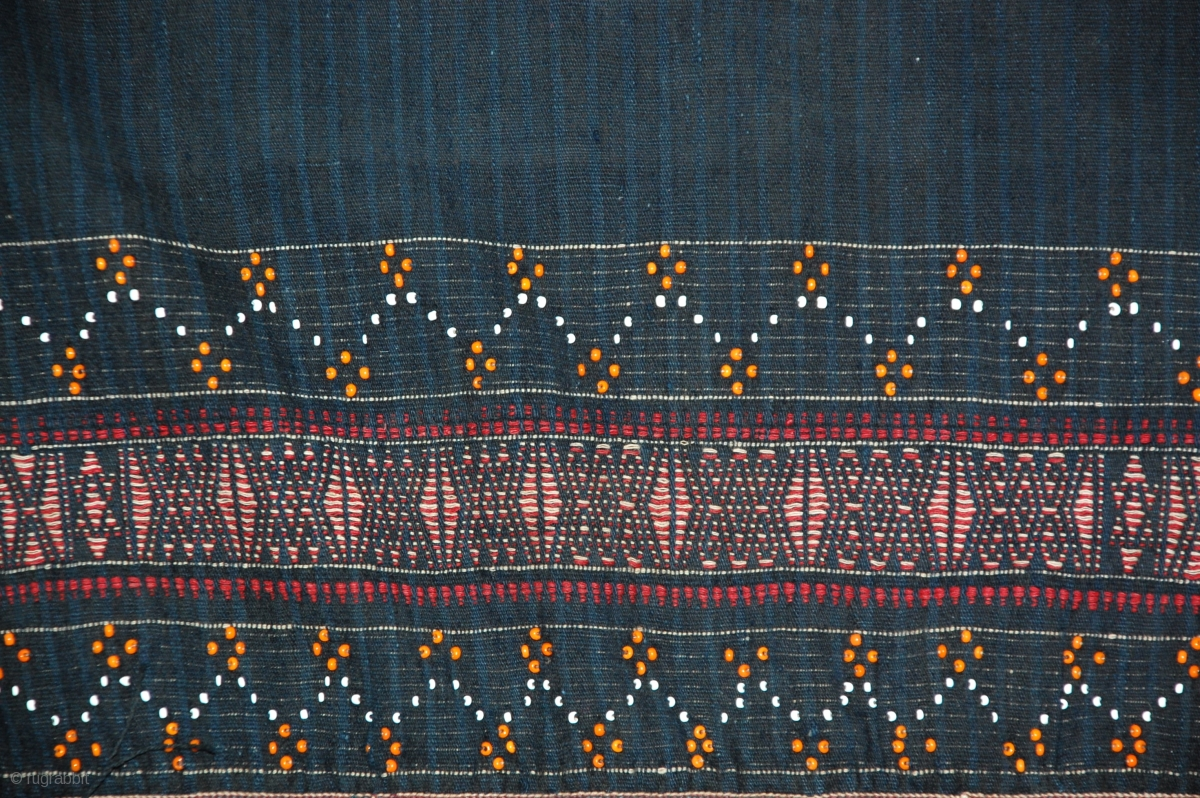

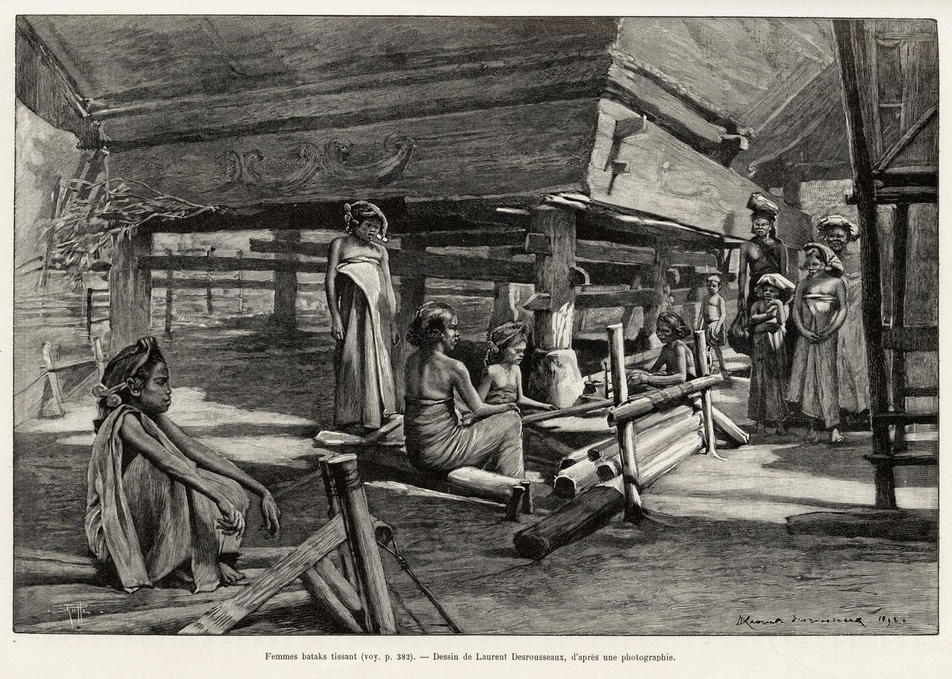

A key theme presented in the film is the central role of women in Batak society as the primary weavers who fulfil both practical and spiritual functions through their craft. Using backstrap looms, Batak women traditionally wove textiles that were integral to family life and community rituals. The designs and patterns of these textiles were believed to provide protection to both the body and the soul, making weaving an indispensable part of prayer and ceremonial life. The designs themselves—often deeply symbolic—serve as a cultural language, reflecting the cosmology, social structure, and values of the Batak people. Through their art, these women played a central role in maintaining and expressing their culture.

Yet, the film also highlights the struggles that the Batak people have faced in preserving their weaving traditions, especially in the wake of colonial annexation in the early 20th century. The Batak were forced to adapt their art to new economic and social realities under Dutch rule, often at the expense of their traditional practices. This historical shift, coupled with the rapid pace of modernization, has contributed to the decline of weaving in Batak communities. Today, only a small number of weavers remain who possess the technical skills necessary to create the traditional textiles. The film sadly captures how, in some cases, the equipment used for weaving has been re-invented or borrowed from other cultures, symbolizing the loss and adaptation of ancient knowledge.

The film’s semi-anachronistic portrayal of Batak weaving techniques serves as a powerful reminder of the fragility of intangible cultural heritage. The director’s note about two non-Batak individuals attempting to reclaim a piece of ancient oral tradition through film underscores the irony of this effort—using modern technology to document and preserve a tradition that is increasingly fading from memory. The narrative voice, coming from a villager more familiar with Christian sermons than with the indigenous tradition of hadatuon(Batak oral lore), emphasizes the extent to which the community’s cultural memory has been disrupted. The weaving techniques that were once widely practiced are now in danger of being forgotten, with only a few practitioners capable of reviving the lost arts.

Despite these challenges, the global recognition of Batak textiles in museum collections serves as a reminder of the cultural value of these weavings. As the film suggests, the value of this documentation increases as the tradition continues to decay. By capturing both the technical aspects of the craft and the spiritual dimensions of Batak weaving, the film acts as both a historical record and a call to action for the preservation of this invaluable cultural heritage.

In conclusion, the Batak weaving tradition reflects not only the skill and creativity of its practitioners but also the resilience of a culture that has adapted to changing times while maintaining its deep spiritual and cultural roots. However, the challenges of preserving this tradition—particularly in the face of modernization and cultural erosion—are immense. The film offers a compelling narrative about the fragility of cultural memory and the importance of preserving intangible heritage before it fades entirely.