Community art as an egalitarian participatory practice

Banghua E. Sun June 2025

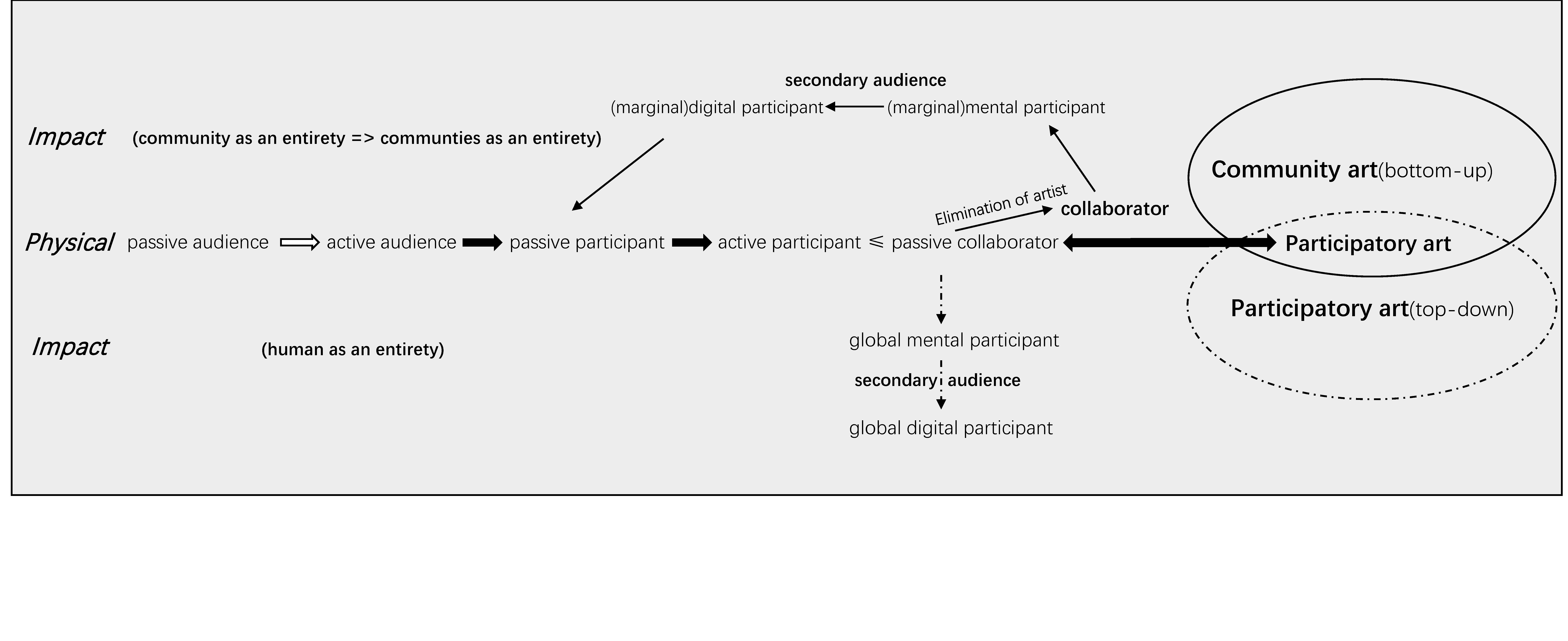

Abstract The most discussed participatory art projects today for their values, are always based on either breaking new ground (or shaking the theoretical foundations of public art, or existing frameworks and definitions), significantly expanding participation (which is still as an important, even decisive indicator), or elevating the audience/recipients to a position of priority (or using local indicators to evaluate success or failure).The results are often hidden rather than immediately apparent on the surface. The core issue here is to what extent the choices of participants are respected, or how to minimize intervention in their choices? This study aims to re-examine the two aesthetic preferences represented by Kester and Bishop—collaboration and antagonism—as an extension of Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics, further developing them into two distinct approaches: bottom-up, community-based collaborative and dialogic participatory art, and top-down, large-scale participatory art. Today, non-community participatory art is generally understood as an attempt to control the audience’s perception and interpretation, exerting a broader influence and gaining favor among critics as a form of post-elite art. Community art, on the other hand, is often questioned for its aesthetic value, with its social value as an priority, being emphasized in the context of excessive intervention by art institutions and governments, resulting in a smaller influence and little attention from critics. If these limitations are overcome, community art can practically enable the public to reach the true “collaborator” stage of participation. This study serves as a further reflection on the position of community art in today’s art world, as presented in Matarasso’s book A Restless Art (2019), and provides a value assessment diagram for participatory art, attempt to clarify the practical value of community art as the significant participatory art through a visual model.

Keyword: Participatory Art, Community Art, Cultural Democracy

Since the 1960s, institutional critique has opened the door to public art, then gradually extending into various media and evolving. As the connection between art and everyday life has grown, public art has shifted to the field of social practice, only to be taken seriously and produce various theoretical constructs in the 1990s. During this period, the academic world was undergoing a dismantling of its professional elitism, and its closed, self-referential ranks were under scrutiny. Art, in order to maintain its critical nature, no longer merely subverts internal forms, it begins to create heterogeneous spaces within human relationships. Viewers are no longer passive decoders of ‘forms,’ but actively participate in the creation of works through action, negotiation, and conflict. The centre of creativity went through a noticeable shift. This term gradually gave rise to various sub-definitions, which are complex yet closely intertwined, each with its own focus and characteristics. But anyway, we can summarise some of the common characteristics of social practice, they all reject the physical accessibility of space, instead identifying it in the relationship with the public or specific participants. As Kwon describes in his third phase of public art, using Chicago’s Culture in Action at 1993 as an example, this seems to summarise the current state of public art development - the “art-in-the-public-interest” mode, named as such by critic Arlene Raven and most cogently theorised initially by Suzanne Lacy under the heading of “new genre public art,” from the disappearance of various types of aesthetic production, from visibility to invisibility, from producers to promoters of relationships and immaterial values among people. This phase can be read as a response to the homogenising forces unleashed by 1980s globalisation and the capitalist colonisation of so-called “marginal” spaces. This phase shifts from the physical location to the social context and the involvement of ordinary people, particularly a specific community. It transforms from site-specific to audience-specific, expanding into “community-specific.” (Lacy 1995; Kwon 2002)

Social practice can be viewed as a “participatory paradigm”, where participation itself encompasses an aesthetic dimension, and this experiential encounter precedes language or art. It is an “experimental knowing” through participatory, empathetic resonance with a being, which can creatively shape a world (Heron & Peason, 1997: 274-294). However, even today, the variety and complexity of case studies far exceed our imagination, actually involving a highly interdisciplinary field that complicates the theoretical foundation of participatory arts, making it “not always very strong or clear, and it is difficult to benefit from rich critical and academic discourse compared to other areas of contemporary art” (Matarasso, 2013:8). Since the 1990s, several critics began to defend the aesthetics of this social practice. After initially questioning the ruthless individualism of modernity and the widespread spiritual crisis and social values of Western civilisation, Suzi Gablik strikes at the root of this alienation by disolving the mechanical division between self and world that has prevailed during the modern epoch (Gablik, 1984). He initially focused on artists who pursued a more comprehensive community framework without compromising aesthetic quality, and it was not until Connective Aesthetics (1992) that he began to defend ‘process’ aesthetics. He underwent a shift in aesthetic preferences, moving from John Ahearn (known for his projects in the Bronx County) and Christo to Mierl Laderman Ukeles’s “Touch Sanitation” and Lacy Suzanne’s “The Crystal Quilt”. (Gablik, 1984; 1995:85) This should naturally spark a debate among critics about the aesthetic value between ‘product’ and ‘process’ in participatory art’s field, but it turns to another debate: after the emergence of Nicolas Bourriaud’s Relational Aesthetic (1998), Grant H. Kester’s ‘conversational aesthetic’ (1999-2000), and Claire Bishop’s ‘antagonism aesthetic’ (2004), while both the latter two build upon and critique the former, offering two distinct value systems for evaluating participatory art – collaboration and antagonism.

At the beginning, Kester considers that many participatory artists still inherit the avant-garde tradition of the “shocking” and the “disruptive”, seeking to “master” the audience’s perception and interpretive authority; in this situation, viewers are compelled to reposition themselves, a process suffused with an ongoing form of class oppression or cognitive violence. He hopes that art can find “a less violent relationship with the viewer while also preserving the critical insights that aesthetic experience can offer into objectifying forms of knowledge” (Kester, 1999-2000; 2004:27). Such well-planned participation will fail to achieve the depth of empathy of viewers at the collective level that is necessary for meaningful interaction. This is why Kester, drawing on Habermas’s model of subjectivity based on communicative interaction, focuses on reflective aesthetic dialogue, for creating “a provisional understanding (the necessary precondition for decision-making) among the members of a given community when normal social or political consensus breaks down” (2004:109). This egalitarian interaction cultivates a sense of ‘solidarity’ among discursive co-participants, who are, as a result, “intimately linked in an inter-subjectively shared form of life” (Kester, 1999-2000; Habermas 1989-90:47). Kester had already considered this idea four years before Bishop published her eassy Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics (2004) on October, as an earlier version of his Conversation Pieces (2004).

In contrast, Bishop denies Bourriaud’s declaration of “social utopias and revolutionary hopes have given way to everyday micro-utopias and imitative strategies” (Bourriaud, 1998:13), she considered “both are predicated on exclusion of that which hinders or threatens the harmonious order” (Bishop, 2004:69), and prefer consistantly to sustain “a tension among viewers, participants, and context” (70). Bishop attemps to adopt Chantal Mouffe and Ernesto Laclau’s conceptual of political antagonism, she regarded as “a democratic society is one in which relations of conflict are sustained, not erased” (66). This approach signals an explicit break with Habermas’s ‘consensus’, which Mouffe critiques naive and covertly repressive form—as the regulative principle of deliberative democracy. It can easily be used to provide a theoretical basis for attacking art practices that involve collaborative interaction. (Miller, 2016:173; Kester, 2024:36, 37). This approach might provide us a means, in the name of art, to defend those who create conflict for its own sake, yet clearly violating ethical norms. Jason Miller conducted detailed analysis of Mouffe with her subsequent clarifications in 2005, distinguishing between ‘antagonism’ and ‘agonism’ which considers the last “introduced to emphasize the importance of disagreement and difference as democratically productive forms of social engagement” (174), criticizing Bishop’s subjective interpretations of the former, which may exacerbate the formal ‘confrontation for its own sake’(ibid.). It is easy to reach consensus through this way because people can “attain a coherent sense of selfhood by taking on an instrumentalizing relationship to other subjects (the other as an ‘antagonist’ or ‘enemy’ to be destroyed)” (Kester, 2024:35). Kester considers that this confrontation could degenerate into violence or fascism—in order to achieve “meaningful self-transformation through extra-parliamentary political action” (ibid). This statement may also be too extreme. Even without any antagonism, while some artists don’t “claim to offer anything like a ‘radical critique’, according to Mouffe, this does not mean that their ‘political role has ended’”. (36). However, only through critical artistic practice can that which the dominant consensus of traditional democratic polities tends to repress, obscure, and obliterate become visible; and only through the “process of introspective self-reflection” will we be guided to foment dissent and abandon our reliance on confrontational violence (Kester, 2024:35, 36; Mouffe, 2007:4). Just as regarded by Matarasso, participation might be seen as a form of cultural democratization, and community aspires to cultural democracy (to be discussed below). (Matarasso, 2019:45,46).

This is not to repeat the debate between Kester and Bishop. Rather, it points out that they represent two aesthetic preferences, they all tend to build a better world. Nevertheless, the antagonism aesthetic will cause kind of critical art all too readily dismisses “the importance of proposing new modes of coexistence, of contributing to the construction of new forms of collective identity” (Miller, 2016:174). Kester adopts a collaborative approach in which projects are collectively developed from the bottom-up, particularly in community art practices. This approach implicitly challenges state-imposed social objectives and breaks away from superficial forms of participation. Such practices offer greater autonomy and are morally preferable to top-down participatory art. At the same time, he believes that “some of the most challenging new collaborative art projects are located on a continuum with forms of cultural activism, rather than being defined in hard-and-fast opposition to them” (Kester, 2011:25; Bell 2015; Miller 2016:173). However, Bishop considers that the harmonious ‘community-as-toghetherness’ as a fictitious pre-requisite (Bishop, 2004; 67). “Bishop’s attempt to reaffirm the aesthetic in socially engaged art does not imply that the aesthetic trumps the ethical, but rather that a second-order ethical imperative for critical awareness trumps any first-order ethical concerns about the nature of aesthetic relations”. She believes that giving autonomy to collaborators not only “is politically limited, as it neutralizes art’s capacity to challenge social conventions”. And it will cause the “aesthetically dubious”, as it leads to uninteresting artworks that fail to be of interest to those outside the immediate collaborative sphere.” Mundane, banal (at least from an elite perspective) and overly bland dialogic art, community-based art, and collaborative art are forms she deeply disdains (Henry, 2012; Miller, 2016:173; Bell, 2015). Emily Watlington also raised doubts about whether Bishop was an elitist in her review of Bishop’s new book (2024), as Bishop barely mentioned digital art, a more broadly accessible medium of popular art. All answers seem to have been clarified when Bishop, in July 2012, introduced her new book Artificial Hells at the Graduate Centre of the City University of New York, uttered the ironic statement - “I am an anti-humanist” (Henry, 2012), as an interesting response to criticism directed at her. This preference may possibly influence the attention and interest of other affected critics towards art from marginalised communities. Such as community artists were regarded normally as inferior to ‘artists’, because the “real artists would be judged primarily on questions of aesthetic quality and only secondarily on questions of social purpose” (Hewison, 2014: 72). This, in turn, led to a conflict between social function and aesthetic quality. The aesthetic quality is obviously more important for ‘an artist’, but even their extreme directions are not irreconcilable.

Bishop have highlighted the importance and critical nature of adopting a rebellious stance in the face of crises in aesthetics and political systems. Especially since she did indeed summarise some of the most serious issues facing community art, particularly when discussing New Labour, where social goals took precedence over artistic goals, and the use of sociological metrics to evaluate outcomes: “social participation is viewed positively because it creates submissive citizens who respect authority and accept the ‘risk’ and responsibility of looking after themselves in the face of diminished public services”. (Bishop, 2012:14). She opposed to the idea of art as a model, as a good example that can be copied and replicated in society, which means ‘art enters a realm of useful, ameliorative and ultimately modest gestures’ (27), it seeks to conceal social inequality, rendering it cosmetic rather than structural and it will bring about this alienation and division in the first place.

This stems from an estimate made based on Matarasso’s 1997 report. It highlights the numerous benefits of community art but also implicit negative consequences of excessive intervention by art institutions, which often adopt a utilitarian approach and measure outcomes based on government-mandated metrics. In his 2019 book A Restless Art, Matarasso provides the most detailed analysis of a range of negative issues of terrible conditions in community art: for most situations, the only basis for funding community art was that it was often due to an overall increase in the budget, and because it ‘might have a certain local, social value’. This is even more evident in remote or marginalised areas, particularly in the south and east, where such initiatives are often unfunded and sometimes politicised (Matarasso, 2019:156, 162, 175). It ultimately stems from the tension between community artists and art institutions—because the work is not created by professionals. Art funding institutions have established a control system over community artists and should reject the institutionalisation of concepts. Matarasso argues that “one escape route is to create art so valued by the system that it loses interest in social questions” (166). The real concern is the ingrained mistrust of participatory art’s intrinsic worth from the artistic institution (196).

Let us return to Bishop’s discussion of ‘aesthetically dubious’ community art mentioned above. This is not only a question of the quality of the work, but also of its inability to spark interest outside the collaborative sphere. However, this collaborative sphere itself is a vague generalisation, seemingly referring to something physical – if not, who constitutes it? In today’s age of digital word, the internet is no longer be seen as only a medium of communication, but is transforming into another context and public space, in constant motion and interaction between the physical world as it is perceived, designed and experienced, and the electronic world. It is a kind of “post-public” space where new relationships between people are experienced on a daily basis (Guida, 2015:30, 178) Community art involves more physical interaction, in essence, the traditional collaborative sphere. How can we leverage the value of the second network space (how to influence secondary audiences) in community art work? Or, are the people who encounter the work through various sensory and relational experiences merely spectators? How can we define the value and standards of a good community project? How can we define the value of a good community art work?

Today, all community artists aim to use their “creativity” to expand the concept of “the arts” beyond passive “encompass more activities and more people”. It is undeniable that it has, to a certain extent, “assisted in the undervaluing of human creativity in general”. “‘Art for all’ (art for the masses) merely expands the supply of existing elite tastes and imposes a single standard on the public, which leads to resources continuing to be skewed towards the elite and dominant cultural institutions, and does not fundamentally solve the structural problems brought about by the ‘Great Tradition’” (Kelly, 1985). A restless and self-critical commitment to making and remaking such judgment is central to contemporary arts practice, which should avoid working within judgment frameworks determined by ‘others’, the professionals whose knowledge and engagement secures them extensive control over their field. There are two most important reasons: “low expectations of what non-professional artists”, and “professional artists do not always offer empowering roles to the non-professionals” (Matarasso, 2019:50). In this situation, the individual creativity will only be suppressed. In fact, this creativity and value scale originate from within social groups. This raises the issue of equality and empowerment between professional artists and non-professional artists within art institutions. Just as Kester quoted British artist Peter Dunn, socially-engaged artist is “‘context providers’ rather than ‘content providers’”. And “these exchanges can catalyze surprisingly powerful transformations in the consciousness of their participants” (Kester, 1999-2000). The usual formulation artistic > audience does not adequately express the nature of that communication (Matarasso, 2019:219). He distinguished between participatory art and community art, although is questionable. However, he did reveal the general understanding of these two terms today: “community art’s lively, mountain spring has become the broad, slow river of participatory art…the whole waterway, from source to mouth, is often described as participatory art” (46). This includes a series of community art movements in the UK from the late 1960s, such as Inter-Action, The Blackie, Action Space, Fun Palace and Welfare State International. He considers that “Participatory emphasises the act of joining in, and implies that there is already something in which to join. Community, in contrast, suggests something shared and collective. It imagines art not as a pre-existing thing, but as the result of people coming together to create it” (45).

One of his insights is that only in community art participants can transform into true collaborators. However, participatory art in the broad sense includes community art. This research suggests, for better distinction, it can be defined broadly participatory art that includes ‘participatory art(top-down)’ and ‘community art(bottom-up)’. The research attempt to create an assessment diagram of value of participatory art for this purpose; at this stage, aesthetic value seems to become gradually secondary, in contrast, it is the main condition for diagram’s evolution.

- This research diagram is based on the traditional classification of participatory art from ‘physical presence’ and does not include fully digital participatory art projects.

- The ‘dotted lines’ represent participatory art (top-down), which are the centre line and lower area of the entire diagram; the ‘solid lines’ represent community art (bottom-up), which are the centre line and upper area of the entire diagram; with the overlapping area in the middle representing broadly participatory art: it does not possess the developmental characteristics of either, but its developmental roots are in the same stage.

- Except for the hollow arrows from passive audience to active audience, which represent ‘non-participatory art’, all other arrows are part of participatory art. Before the passive audience, there are artists (initial). As shown in the figure, participatory art (top down) can reach the stage of active participant or passive collaborator. The artist still exists and remains the creator of conditions/contexts. It do not have the practical motivation such as community art, or the practical to change is slow (influence decision-makers in the central power structure). It emphasizes momentariness, it has more ambitious goals, facing a global non-marginal/central (or elite) secondary audience covering a wide area—due to its aesthetic value, it has a large reach and aims to spread mentally to more people, with the ultimate goal of the idea of ‘human as an entirety’, it can be seen a post-elite art.

Community art seeks more long-term impact, whether on an individual or collective level, and, it may achieve the ultimate evolution of participatory art in terms of individual creativity from that collective. Only community art (bottom-up) can reach the collaborator stage – with extreme decentralization:at the end of this stage, it will eventually completely dissolve not only the identity ‘as an artist’, but also that of the ‘social agent’ and ‘service provider’. Not only does the initial artist dissolve, but all participant artists also dissolve in the process (or everyone are artists), and even more, everyone becomes a leader. Cultural democracy is the most important condition at this stage.

Matarasso believes Cultural democracy may be the least oppressive from a cultural policy as the defining goal of community art (78). As he quoted J. A. Simpson’s report Towards Cultural Democracy in a conference of European ministers of cultural in Oslo at 1976 organised by the Council of Europe:

“Cultural democracy implies placing importance on […] creating conditions which will allow people to choose to be active participants rather than just passive receivers of culture” (74).

He asserts three conditions to make ‘passive receivers’ to ‘active participants’: 1) Have access to knowledge, training, space, time and resources. 2) The whole process has the qualifier of ‘fully, freely and equally’. 3) The participants have to act as an artist. He cited Article 27 of the Universal Declaration of human Rights (1948):

“Everyone has the right freely to participate in the cultural life of the community, to enjoy the arts and to share in scientific advance ment and its benefits”. (44).

Only under these circumstances can it avoid John Robert’s criticism of the ineffective ‘micro-utopias’: “imposing a coercive consensus on the complex and multivalent personalities of individual participants” (Roberts, 2015:55). In addition to Matarasso’s 1997 report, numerous qualitative studies have shown that there are close ties between community members or communities, and community art serves as an important means of social cohesion. People participate more as a collective, with a sense of collective identity, belonging, responsibility, and a sense of mission are strongest among collaborators— ‘the community as an entirety’. At this stage, everyone is equal. It will eventually spread to other communities that share common characteristics. Secondary audiences will move from aspiring to participate—or already being mentally engaged —to digital participation (which includes activities also like commenting, giving likes and sharing), and then to passive participation (whether by joining this community or others). In doing so, it forms a continuously active closed loop: all ‘communities as an entirety’.

Matarasso also considers the deeper implication of cultural democracy – “is that culture, and its meanings, values and standards are not fixed and universal but the result of a continuing process of (sometimes) democratic negotiation between people” (77). “It is filtered through the situation, experience and imagination of those who encounter it and is invested with sense and value accordingly”. He sees this relationship as linking creator >< recreator in a shared process of meaning-making (97, 98). How can everyone participate equally and create valuable works in a community art project? John Carey said: ‘Value […] is not intrinsic in objects, but attributed to them by whoever is doing the valuing’. (Carey 2005:xii). So the work of community artists become to foster conditions that generate this kind of value. The community artists (initiators) have to take out harness their creativity to create the conditions that stimulate participants’s passion, gradually turning them into equal collaborators. Only Through participatory practices, the initiators’ creativity will be decentralized, redistributing creative agency among collaborators over time. What requirements should community artists have? Are these requirements common for all community artists? Both values and requirements should be assessed differently in each specific community. If “process and product are yin and yang in participatory art, stable only in mutual dependency” (Matarasso, 2019:97), then isn’t the same for social value and aesthetic value, collaboration and agonism?

Reference

Bourriaud, N., Relational Aesthetics, translated by Pleasance. S. & Copeland, M., Les presses du reel, 2002, original published 1998.

Bell, D. M., The Politics of Pariticpatory Art, Political Studies Review, ,2015.

Bishop, C., Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics, October No. 110, MIT Press, pp. 51-79, Fall 2004.

Bishop, C. eds., Participation, Whitechapel and MIT Press, 2006.

Bishop, C., Artificial Hells, Pariticpatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, Edinburgh, 2012.

Carey, J., What Good are the Arts?, London, 2005.

Gablik, S., Has Modernism Failed?, Thames and Hudson, New York, 1984.

Gablik, S., Connective Aesthetic: Art after Individualism, In S. Lacy eds., ibid, pp. 74-87, 1992.

Guida, C., Spatial Practices, Funzione pubblica e politica dell’arte nella società delle reti, FrancoAngeli, Milan, 2012.

Heron, J. & Reason, P., A Participatory Inquiry Paradigm, Qualitive Inquiry, Volume 3, N.3, 1997, pp. 274-294.

Hewison, R., Cultural Capital: The Rise and Fall of Creative Britain, London, 2014.

Kester, G. H., Conversation Pieces: The Role of Dialogue in Socially-Engaged Art, Variant #9(Winter 1999-2000), 2000.

Kester, G. H., Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art, University of California Press, Ltd. London, 2004

Kester, G. H., The One and The Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context, Duke University Press, Durham and London, 2011

Kester, G. H., Beyond the Sovereign Self: Aesthetic autonomy from the avant-garde to socially engaged art, Duke University Press, 2024.

Kown, M., One Place after Another: site-specific art and locational identity, MIT Press, Cambridge, 2002.

Kelly, O., 1985, ‘In search of Cultural Democracy’, Arts Express, october 1985, pp. 2-7.

Lacy S., eds., Mapping The Terrain: New Genre Public Art, Bay Press, Scattle and Washington, 1995.

Henry, J., Straight to Hells, The New Inquiry Magazine, 2012 https://thenewinquiry.com/straight-to-hells/

Matarasso, F., A Restless Art: How participation won, and why it matters, Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, UK Branch, 2019.

Matarasso, F., ‘Creative Progression: Reflections on quality in participatory arts’, UNESCO Observatory Multi-Disciplinary Journal in the Arts, Vol. 3 no. 3, Melbourne, 2013, pp. 1-15.

Matarasso, F., Use or Ornament? The Social Impact of Participation in the Arts, stroud, 1997.

Miller, J., Activism vs. Antagonism: Socially Engaged Art from Bourriaud to Bishop and Beyond, FIELD (A Journal of Socially-engaged Art Criticism), pp. 165-183, winter 2016.

Mouffe, C., “Artistic Activism and Agonistic Spaces”, Art and Research: A Journal of Ideas, Contexts and Methods 1, no. 2 (Summer 2007): 1–5

Roberts, J., Revolutionary Time and the Avant- Garde, New York:Verso, 2015. Watlington, E., Claire Bishop’s New Book Argues Technology Changed Attention Spans—and Shows How Artists Have Adapted, Art in America, 2024.