Abstract

In this exposition, I discuss the multimedia installation Esparto, approached, to which I opened doors last May 10th, 2025, in Organo Hall, Helsinki Music Center. Esparto, approached is the first of a series of three installations representing the artistic component of my doctoral degree at the Sibelius Academy, Uniarts Helsinki. The research project in which this installation is contextualized is currently titled "Listening through remembrance: An autoethnography of presence in the age of disposability". In this artistic research, the notions of listening, remembering, and presence-making are interwoven in an attempt to understand how we confer meaning and value on things despite our embeddedness in a world of disposable nature, where things are susceptible to being quickly discarded, replaced, and, therefore, forgotten.

This exposition opens up a space of reflection in the aftermath of Esparto, approached. The installation represented a collective recall of the field practice that led me to search for signs of durability in abandoned contexts of my homeland in rural Southeastern Spain. This exposition poses the following questions about it: What happened? (Description); What does what happened mean? (Analysis); And, how does what happened keep happening now? (Further becomings). The objective of creating an online exposition right after the event is to open a window to the reflective process of this investigation before its completion, thus making visible its traces. The process itself is therefore turned into an accessible outcome that manifests the continual nature of the project as a whole.

TIP: Navigate the exposition by scrolling toward the right of the screen.

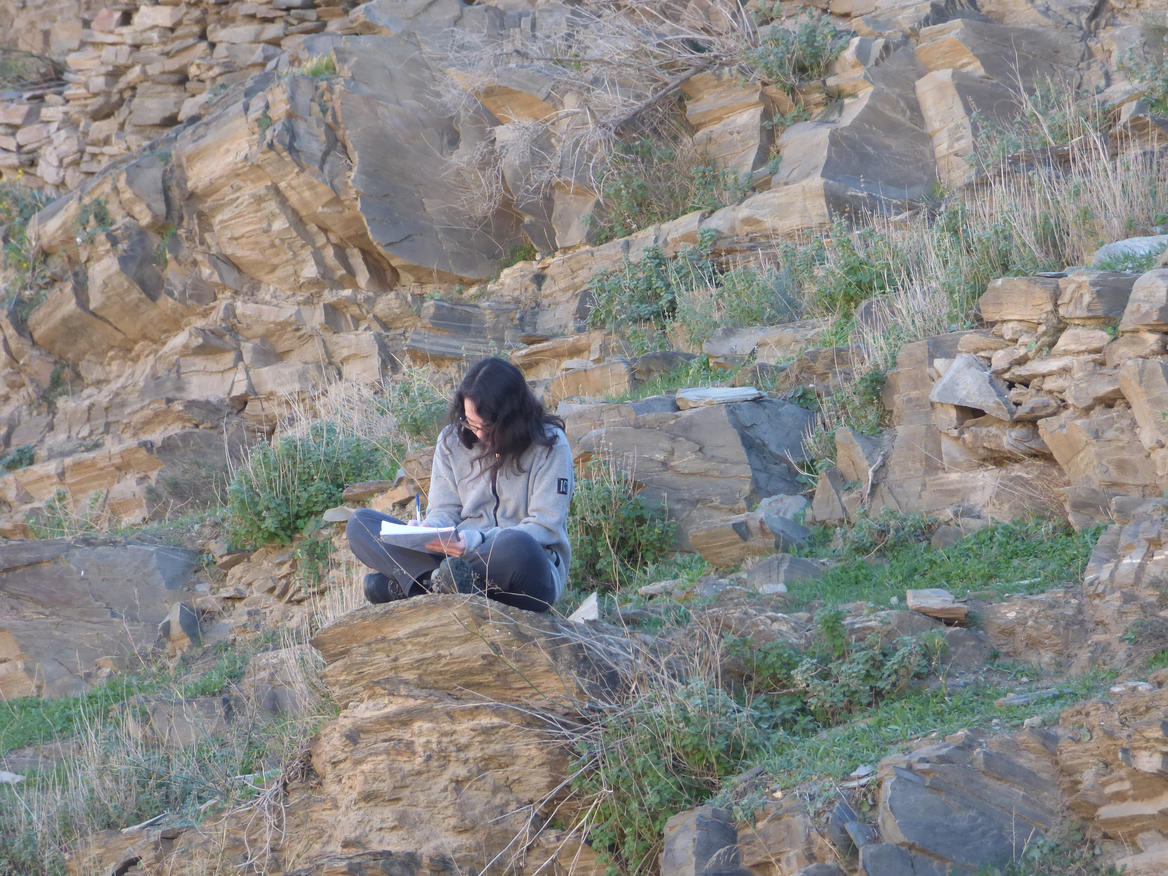

Wandering around the ruins of Bueso family’s farmhouse (Abla, Spain). Photo by Juan A. Miralles. December 2024

***

Many stories intertwined during those field trips. Stories about objects that went missing for real and were never found to be recorded; stories about places that were gone, paths that could no longer be accessed due to erosion; stories about things turning unrecognizable, expectations being frustrated, and the strong resilience of working with what it is, of encountering memory in its now, instead of grieving what it was (or used to be). I too had changed before coming back to them, and so this resilience was reciprocal.

***

Introduction

Artistic practice happens in time, in a time that won’t repeat. However, the meaning of what happened continues to change over time due to new happenings, new frameworks, new ways of understanding its process and outcomes from the point of view of the relative present from which it is looked at, recalled, remembered. And so, even if what happened in the artistic practice happened in time, and in a time that won’t repeat, what happened is not fixated in the past but continues to be conferred new meanings in the present and confer itself meaning on other things that are happening or will happen. This continuity of signification (the continuity of being constantly (re)signified) is a key concern of this research project.

Taking that into account, a side note about this exposition is needed here: I decided not to wait until all my artistic doings were “concluded” so that I could look at each of them from the idea of a whole, and from the frameworks and meanings that I would settle with when I decide to write a full stop (or perhaps more like a semicolon) to this research project. I decided to write now, right after this first moment of sharing with an audience. I thus decided to open a window to the traces of the process, even if they seem outdated with respect to the moment they are revisited, to demonstrate once again that they continue to be present precisely because of their constant (re)signification. And the process of remembering these traces is what contributes to conferring (new) meanings on what is happening now.

But then, leaving aside these initial abstract considerations, what is it that happened at that first moment of sharing with an audience? Last May 10th, 2025, I opened doors to Esparto, approached, the first of a series of three installations representing the artistic component of my doctoral research at the Sibelius Academy, University of the Arts Helsinki. Over forty people spent some time in Organo Hall, at the Helsinki Music Center, over the four hours that the installation remained open. It was also my first time experiencing all its components being put together, interacting with each other, creating a context of their own. This exposition offers an opportunity to “re-compose” the journey that led, perhaps not to May 10th, but to the moment in which I write these words, as the process has remained (and will remain) open since then as an artistic outcome on its own. The exposition will consist of two parts: the first one will focus on what happened, and the second one will move toward the (current) meanings of what happened. That is, there will be some sort of description and some sort of analysis, if we were to be rigorous with the conventional research structures.

What happened

The research project in which Esparto, approached is contextualized is currently titled “Listening through remembrance: An autoethnography of presence in the age of disposability”. In this artistic research, I am looking into the concept of presence to explore a relationship with the world that is not based on disposability, that is, on fast-paced discard and replacement (and, therefore, forgetfulness). For that, I am using the notions of remembrance and listening to find (or even create) the “anchor points” that we need to acknowledge ourselves as part of the reality we inhabit. Jean-Luc Nancy’s continual ideas on presence and listening related to remaining open to the unfoldings of the world[1] represent one of the theoretical pillars of the research. My objective is to understand remembrance as an access point to this kind of attitude toward the world, allowing meanings and values to be continuously restored thanks to a sense of familiarity, intimacy, and closeness. These ideas will be further delved into in the second part of the exposition, but this brief introduction could come in handy when understanding Esparto, approached as part of the project as a whole. My field practice takes place in my homeland, in rural Southeastern Spain, and the images, sounds, objects, and voices collected from it are collectively recalled in a series of three multimedia installations in which I invite the audience, back in Finland, to further engage with their own remembrances. Esparto, approached is the first installation of this series.

But “Listening through remembrance” (and the sort of abstract I crammed in the previous paragraph) is how I conceive my artistic research project now. Back in October 2024, when I first stepped out in the field with an old sound recorder and a flimsy phone tripod, “Listening through remembrance” was only subconsciously incubating. I discovered the disposability of our world, the possibility of listening through remembering, and the autoethnographic approach to presence while practicing in the field and recalling the field practice, and it is only now that I am verbalizing it using these precise words, which might change (or better reshape) as the now extends further on. Two more field trips happened in December 2024 and February 2025, respectively, before I started to conceive a way of sharing my experiences in there with the people in here, so that the process turned into a more collective (or at least shared) inquiry, which is what I eventually aimed for in Esparto, approached (and what I still strive for as the artistic process heads toward the next installation of the series).

[1] See, for instance, the example presented by Haroutunian-Gordon & Laverty (2024, 937–938): “We interpret Nancy to be saying that when the man enters a room repeatedly, he is not the same self each time. Each time he enters the room, he is a different self, different because he is in a different relation to the objects in the room than he was previously. Thus, in Nancy’s story, the ‘he’ is thought of as newly created selves that are defined by the sets of relations […] that are successively dis-posed moment by moment” (Nancy’s story comes from Being Singular Plural, 2000).

What was clear to me was where to go, and this choice already bore the questions that would accompany me during the whole process. These were places in my homeland, in rural Southeastern Spain (Almería), which I knew well. Yet they seemed abandoned or stripped of meaning or purpose for some reason I did not understand at the moment. And so, the practice simply consisted of going there, of being there, of sensing there. Of figuring out what happened to these places that I once knew, but did not anymore. To these places I had forgotten in a way and from which I could perhaps retrieve the shared memories of dwelling, utility, and meaning that they still held despite their abandonment. These were the preliminary questions:

What remains of what I remember?

Can I restore the memories that have already faded?

And how do I find meaning in those memories?

The field practice

The practices of going there, being there, and sensing there weren’t planned in advance. I knew I would go to these places, I knew I would bring the sound recorder and a tripod for my phone to document the practices, and I knew this documentation would somehow become the material for the installation itself, but I did not know exactly what to do in there. The reason for this was my lack of expectations regarding how these places (and the objects in them) could have changed, and so I could not predict my needs when approaching those preliminary questions through my mere presence there. This is something clearly reflected in the field diary excerpt that I included at the very beginning of the exposition. When going through the documented materials, one can notice a series of simple reactions that turned into the so-called practices of inhabiting those places (of being there and sensing there, or of “tuning-in”, as Sabine Vogel would call it[2]):

[2] See: Vogel, Sabine. (2015). "Tuning-in". Contemporary Music Review, Vol. 34 (4): 327–334.

Recording (sound / video)

Writing (on site / off site, and on camera / off camera)

Sitting

Lying down

Touching

Making sound (sound intervention, e.g. in a place / sound activation, e.g. of an object)

Enacting (e.g. a practice)

These practices were often combined in different ways (e.g. when touching something, I’m also sitting somewhere and making sound out of that gesture). Listening (and sometimes gazing) was continuously (and inevitably) present when performing any of these practices, which contributed to starting thinking of any of these processes as a form of “making sound” (or “sounding”). I will delve further into the possible sonic significations of these practices (and of the project, on the whole) in the second part of the exposition.

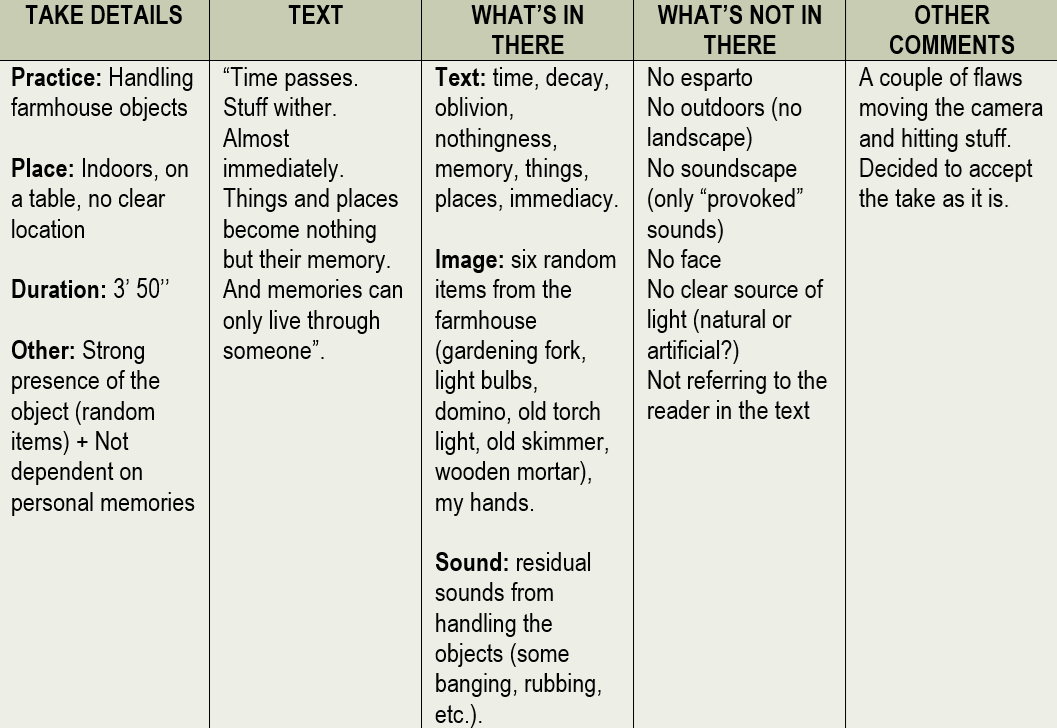

The inventory method was used as a strategy to register the recorded materials and, later on, as a tool for the decision-making of their organization in the installation. The inventory included information about the kind of practice done, its place and time, its duration, the text (whether written on-site or off-site) linked to it, what one could see, what one could hear, and things that I considered “missing” compared to other materials, alongside other comments. Here is an example of how one material looks like on the inventory table, which ended up hosting 21 materials at the end of the field trips:

The inventory provided a meaningful source of unplanned connections (among topics, places, images, sounds, etc.) between the different materials, which were considered later on when creating the two videos that were finally displayed as part of the installation. In the end, the inventory table represented a way of tracing meaning across the different moments of the field practice.

Esparto grass

Throughout the field trips, a specific element represented by a place, an object, and a practice at the same time, seemed to acquire increasing importance up to the point of becoming the thematic center of the artistic process. Esparto grass is a kind of vegetal fiber harvested for thousands of years in my homeland in Southeastern Spain. With it, people used to handcraft all sorts of everyday life and agriculture supplies, being especially important in ropemaking and basketry. This tradition waned significantly since the 1970s, finding other purposes and contexts of practice in recent years[3]. I (re)encountered esparto grass through the traces that my grandpa, who passed away when I was a child, left behind in the form of objects, bundles of grass, and the faint memories that my parents still retain, and so this object (esparto grass), the places where it grows (called espartales), and the crafting practice linked to it (esparto braiding) turned into a cultural tie I had forgotten and thought of remembering and (re)signifying through these traces with special care in this project. Even though esparto grass is not the specific focus of my research questions, it has turned into an anchor for the artistic practice linked to them to be better understood as a self-narrative.

The installation

The function of the installation series is to provide a context for collectively recalling the images, sounds, objects, and voices gathered throughout my field practice, and to possibly encourage the audience to further engage with their own remembrances through this shared recall. It is important to notice, nonetheless, that the images, sounds, objects, and voices present in the installation are always somehow mediated[4]. Mediated by technology in the case of the sounds and images, mediated by my own words when verbalizing my reflections and displaying them as subtitles, mediated by the hall, which is not the space where the practice took place, etc. And the list is endless. In any case, the question of mediation is only important when making assumptions about the kind of experience that the audience should have at the installation (which is something I have tried to avoid), especially in relation to the sensorial information that might be missing. For instance, the audience cannot feel the warmth of the sun or the breeze I experienced at home through a videotape, but they might think of their home, adapt to its own light, the way they know it feels in there. I will never, in exchange, get to feel that.

[3] This kind of vegetal fiber grows in other parts of the world, namely in Portugal and the Maghreb (e.g. in Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, or Egypt), and it is possible that the history and culture of its usage developed differently there. In order to avoid making assumptions about these other historical and cultural contexts, I am referring to this plant and its tradition in my homeland as “esparto”, which is the specific name we use there.

But leaving aside the question of mediation, a decision was made to create two videos out of the 21 materials I had recorded during the field trips, keeping esparto grass as a thematic center in the form of a recurring element among these materials. These videos comprised three main elements, namely, text, image, and sound, which, as mentioned before, were interrelated among the different materials, generating narratives that I had not planned beforehand and that were only discovered while working on the materials at the studio back in Finland. The work at the studio consisted of revisiting the documented materials, and sometimes reacting to them by writing an off-site text. I had no intention of processing the recorded image or sound (other than adding the texts as subtitles), that is, I wanted to keep these elements in their rawest version. With this, I just sought to reflect the artistic practice as a process and not as a result. There was no need to “create” something out of the material as the material (meaning the practice, and hence the process) was itself already an outcome on its own, although the subsequent installation is, in a way, a processed result of gathering this material together and making decisions on how to share it with the audience.

The two videos were displayed simultaneously on opposite walls of the hall and looped during the opening hours. Because of this layout, the audience had to make a choice regarding what to focus on at each time, being able to watch each video entirely or combine them in different ways. The fact that the videos had different durations (52’ and 20’ respectively) also prompted different relationships among them at different moments during the four hours that the installation remained open. The video projections were also different in size, with the right-wall video being displayed on a smaller screen and vice-versa, suiting the contrasting character of the materials as it will be explained later on.

The texts accompanying the videos were displayed as subtitles in English. There was no voice cover because I considered it a very invasive element in the installation, which would have rendered the text as unavoidable as the sound environment (as it would have been turned into part of the sound environment itself, a part of it that carries semantic content and, therefore, a heavy “burden” for the audience). The text as image can be “looked away from” in contrast with the text as sound, which cannot (I will delve into this idea later on in this subsection). I provided the audience with a link to the texts in the program notes because I wanted to give them the opportunity of coming back to them, if needed, precisely because they can be “looked away from”. This was, however, a difficult decision, as I considered that the texts made no sense if taken out of their context in the videos, or perhaps they made sense, but in a different way that I had not contemplated before.

Installation layout on the setup day in Organo Hall (Helsinki Music Center). Photos by Pilar Miralles. May 9th, 2025

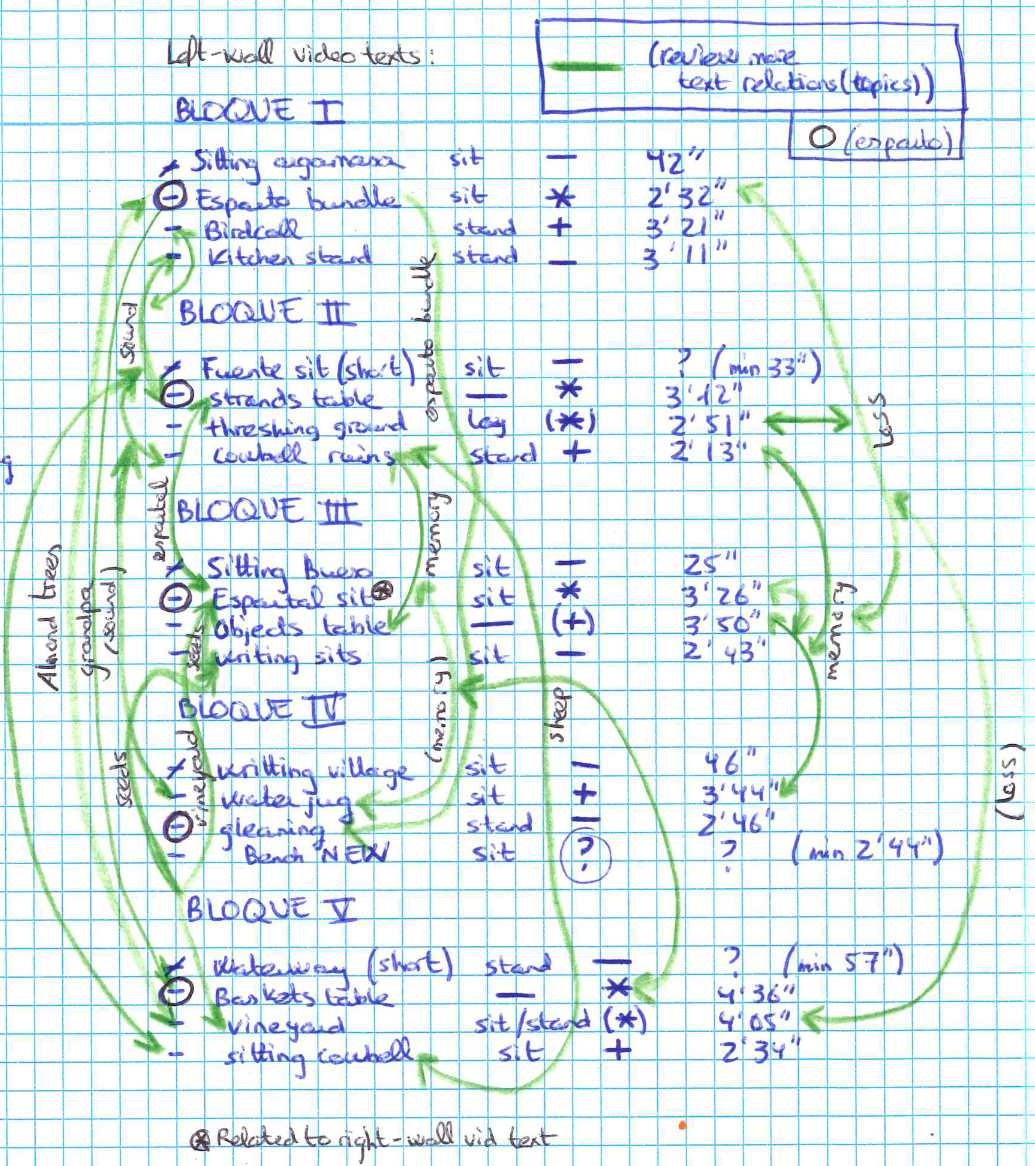

- The video on the left wall (52’) bears a more reflective character, resembling the work at the studio while revisiting the different moments of the practice on site. It consists of a succession of 20 short videos (ranging between 30’’ and 5’ each). There is no apparent narrative connection between the short videos, but the complete thing does acquire meaning as a whole due to the before-mentioned common elements that can be traced among the displayed images, sounds, and words. When I started to work on this video, I thought the order of the short videos did not matter, and so I would not think about it, at least from a narrative point of view. Eventually, certain aspects of the short videos, identified as well in the inventory table, eased the decision-making process in this respect. Some of those aspects were the recurrence of esparto grass throughout the complete video, the balance between videos with heavier or lighter text or sound content, etc. This kind of compensating work also contributed to the fact that the complete video can be watched and understood from any point of the loop onward.

An example of how the process of sorting and relating the short videos looked like can be observed on the right-hand side:

- The video on the right wall (20’) bears a more contemplative character, conveying the work on site from a “real-time” perspective. It consists of a single video that summarizes the exploration I carried out and documented in an espartal (the place where esparto bushes grow). The sound of this video, which consists of waves from the sea, the wind, and some sparse birds, created a continuum in the space that contrasted with the sound environment changes occurring in the opposite video, at some moments being masked by it and at some others filling up its sonic gaps. The text included in this video, in contrast with the somewhat narrative character of the texts in each of the left-wall short videos, consists of an array of short sentences that linger over the image for a longer time and can be read from any point onward. This sort of non-narrative contemplation was built around the iterated phrase “I’m an esparto bush”. Some time after the video was created, I realized this text created a certain “tension” as one is not really sure whether it is the esparto bush or the person appearing in the video who is talking. In my experience, it comes back and forth: sometimes it's the plant, sometimes it’s me speaking out through that text, as in the video sometimes I’m there, but sometimes I disappear and it’s just the bushes, the sea, the sun, the breeze.

Alongside the two video projections, a space in the center of the hall was dedicated to a series of objects made of esparto and bundles of esparto grass that the audience was invited to touch and spend time with (either while watching the videos or as a separate experience). This space was meant to allow the audience to create a memory of their own from esparto grass. I wondered whether it could remind them of something they knew, as handcrafting with vegetal fibers is something common in many different cultural contexts[5]. The touch (and even the smell) of the grass also offered an additional sensorial layer to the installation with a strong connection to what was shown in the videos. Indeed, some of the videos showing esparto objects being manipulated were especially successful in encouraging the audience to mimic such gestures with the objects present in the hall, perhaps in order to relate to the displayed situation while having a direct experience of the material. All the esparto objects shown in the videos were available in the hall (alongside other objects and grass I had collected during the field trips), and so this added a certain intimacy to the experience, backed by the story behind the objects that was told in the videos.

Example of structure for the left-wall video, including topic relations explored among the different clips

The sound accompanying the videos, which simply consisted of the raw sound environment captured at the moment of recording the practice (including sounds present at the site “by default” and sounds produced and/or provoked by my presence/practice at the site), ended up being a central element of the installation even if its importance was not intentionally raised over that of the texts, the images, or the objects in the hall. The reason for this is simple: as suggested before, sound cannot be “looked away from”: “The ears don’t have eyelids” (Nancy 2007, 15). While one can focus their attention on one video or the other, or none of them (e.g. when touching the esparto objects), the sound coming from both video projections becomes some sort of subliminal presence that is unavoidably constantly there. This led some people from the audience to experience the sound by itself (e.g. lying down with their eyes closed and therefore not engaging with any other element in the installation). The installation turned out to offer a myriad of multimodal experiences, unique for each visitor and dependent on the moment they entered the installation and the way they approached it (whether sitting down, standing around, lying down, or combining different approaches). These two factors created a unique combination of materials, attentions, and subsequent reflective processes.

Here is the video summary of the installation:

It might be a good moment to sort of "re-create" the installation in this online space, even though I can only present here the purely audiovisual material. The texts will be separately provided as well, just like I did back in May through the program notes. Just bear in mind how differently they could be signified when subtracted from their context in the videos. The two videos can be played at the same time, so that a more accurate experience takes place. You may watch one and then the other in any order, or switch from one to another at any time, any number of times. Your eyes may take a rest, and you may only focus on the sound at some point. You may spend 5 min or 4h (re)visiting these materials.

“There is a certain scent of abandonment around. My mom said that all the almond trees dried up recently. We used to harvest almonds here. There is a dried almond tree right behind me. I feel its eyes fixed on my back. And I let it watch me calmly. I’m holding an old bundle of esparto grass. It’s yellow because it too is dry. But esparto is usually left to dry on purpose, so that it is more resistant when braided into baskets. This bundle was most likely collected by my grandpa. But he is no longer around to use it, and so it was abandoned to this state of not-becoming, but just being unfinished”.

“I apologize beforehand for disturbing the somewhat opaque silence of the space. I’m trying to inhabit the place, to situate myself through this sonic activation. I’m intervening sonically in the space, wondering whether it will take me in or not. I blow into the whistle and stand around, looking for an answer. I can hear some sparse birds, but they are far away. They might be saying hello, or telling me to shut up”.

“This kitchen… It’s missing something. … (thinking what’s missing) … It’s missing the milk bottle. We used to leave it next to the window overnight, so that the milk was cold in the morning. … Can you hear the clock? That clock… It keeps sounding even when no one is here. Does time also keep passing by in here, when there is no one to hear that clock?”

“When touching these strands of esparto grass, my hands felt a bit sticky and dusty. And I thought it made sense since this doesn’t come from an arts and crafts shop. This was just harvested by my dad from a dusty field. And it would have been very romantic if I said that it came from one of those bushes that sits next to the sea. But this was probably collected next to a gas station, in the middle of the road, where my dad could just leave the car, walk for a hundred meters, and pick up some strands. Esparto grass is that resilient. It can sleep on the shores, lulled by the sound of the waves, or rest by the roads, and get used to the constant roaring of the cars and the smell of burnt fuel”.

“I’m becoming a stone, one of these flat stones surrounding me. They were placed here by someone. This place is a threshing ground, where they used to prepare the cereals to make bread. But it hasn’t been used in many decades. And so now wild grass grows in between the stones. These stones have endured the threshing of wheat for many years. Now, they become wild stones again, although displaced from their original place in the world for their human use. That sounds familiar: to be displaced for human use. And to inevitably remain available for it, and exposed to its erosion”.

“Time is sound. Or perhaps time always sounds. There is always something sounding. That is why I say that time is sound. My memories do sound as well. Even when they are mute, I can still hear myself breathing. It’s been so long since the shepherd slept over in here. But I can still hear the sheep. They sound as I breathe”.

“I’m in an espartal, the place where esparto bushes grow. I can hear the sound of the waves, not so far away, lulling me to sleep. The wind rocks me slightly, and the sun warms me up. As time passes, I feel more like a bush, less like a person. Some of these bushes will stick around for several decades. I’m just remaining with them for a few minutes. Remembering, imagining…

I saw the wooden posts that used to support the lush vineyard. They had all toppled to the ground after the vines dried up, lying down calmly among the dead trees. They will be swallowed by the mud, and become one with the soil again. Perhaps host a new seed, and start again the cycle of simultaneous growth and decay”.

“Time passes. Stuff withers. Almost immediately. Things and places become nothing but their memory. And memories can only live through someone”.

“I’m sitting here and I feel that I am present. At this very moment. I don’t need to think about what comes after this very moment. I am.

Living in the future means dying a bit. But we don’t believe that. We believe that going backward means dying, a bit. So, I am showing you that it’s okay. I am allowing you to come back to this very moment. And this very moment becomes your very moment now.

When coming back, we can always bring with us what we have learnt. And perhaps water a seed that we had forgotten in there. Because we went forward too fast. I think there is still time for it to grow”.

“This thing doesn’t sound like I had imagined. It’s more difficult than I thought. I am not finding the objects I was searching for. Or the places. (Or the sounds). One needs to re-create them. One needs to make them again, but not like they were before, and rather like they still are. That’s what things do. They remain. Even if it’s just as dust. As specs of sand, rubbles, splinters. I remember drinking water from this clay jug as a child. Now it’s barely clinging on to reality. Resisting oblivion through my memory. And in spite of it. And this broken jug will crack even further, and shatter into pieces, and dissolve back into clay. And one day someone might collect that clay and turn it into a new water jug that someone else will remember”.

“Un manojo de esparto, which stands for “a bundle of esparto grass” in Spanish. Manojo comes from mano, which means “hand”. Esparto grass is harvested with the hands and gathered in bundles that can be grasped with a hand. A handful of esparto grass. Don’t worry. Collecting esparto doesn’t harm the plant. But I still apologize, and thank this bush for its generosity, every time I bend down and pull with my bare hands”.

“The world is full of paths. They cover the lands like our circulatory system, marked by the footprints of people from that time when there were no trains, no cars, no planes, a mule at most. Most of these trails reach nowhere anymore. Perhaps an abandoned village full of ruins that look at any stray visitor through the emptied eyes of their windows. Benches are part of these paths’ trace. A sign that people used to wander this way, and rest at this point. I don’t know what their destination was. But I have the sensation of bearing that tacit knowledge and the inertia of participating in the shaping of the path. I too felt the need to take a break here”.

“Two baskets. I took these from my parents’ place in Almería, in Southeastern Spain. They said I should take good care of them. They were handcrafted by my grandpa. He died in 2007. I was ten. Grandpa Juan José was always doing something at the farmhouse with his bare hands. He was always immersed in a process, whether that of building, taking care of, or letting grow.

I feel this material could last forever. It’s dried esparto grass. It’s left to dry for a long time. Then, it’s soaked in water for a while and sometimes they spank it with a wooden mallet to soften it. And then, it can finally be braided and woven, tightly, just like in these baskets. Grandpa Juan José could have braided these under my very nose. But I was too young to care about esparto grass. I don’t remember him braiding esparto. Thus, I can only imagine him”.

“I called my parents, told them where I needed to go make my recordings. I wanted to come back to the old family farmhouse. But my mom warned me about idealizing the place: ‘The walnut tree has dried up’. ‘Many trees have dried up’. ‘Don’t expect to find in there what you left behind’. I wondered if I would be strong enough to bear the loss. And, beyond bearing it, to lay out new narratives out of it. The walnut tree is dead. The almond trees are dead. This vineyard is a graveyard. But I didn’t come here to inhabit the past, but to re-encounter the present. Because dry trees still remember the hand that sowed their seeds”.

“All I wanted was to hear the sheep again. To hear the sound of the sheep in the barn, as the day comes to an end. I didn’t want to write a piece about it, but to be there. Present. Again. And I thought: If I cannot bring the sheep back, (or if I cannot bring myself back to the sheep), then I need, at least, to create an imaginary idea of them. Of their sound. To seek shelter in”.

“I’m an esparto bush

The waves lull me

The sun warms me up

I’m an esparto bush

The wind rocks my leaves

The soil nurtures me

I’m an esparto bush

I was here before you came

I’ll still be here when you go

I’m an esparto bush

I’m lush

I’ll wither

I’ll become one with the soil again

I’m an esparto bush

I’ll leave a seed

I’ll grow again

I’m growing and withering at once

I’m an esparto bush

Slowly

Slower than the tides

Slower than the sun

I’m an esparto bush

I am slowly

I am quietly

I am calmly”

Aftermath

To wrap up this first part, I would like to include some comments about the installation that I took note while revisiting the documentation of that day at the hall and after being approached by some of the colleagues attending it:

I realized that the worst moment in any installation is the opening time, in which people have no reference of how to approach the space. It is also an important moment, as people coming in first are the people “making” the space. People coming after, when there is already someone in the space, can also “make” their own space, but they will always be influenced by how other people are approaching the installation. It took some time for people to decide where to sit, whether to touch the objects, or which video to look at first.

Something that surprised me was the amount of time people spent at the installation, which in many cases surpassed the loop time of the videos. I was worried that the narrative of the installation on the whole was too “slow” for the audience, but that didn’t seem to be the case. On the other hand, it also surprised me that almost all visitors touched the esparto objects at some point. They seemed to be interested in how the material felt (or even smelt like), especially after the grass or objects appeared in the videos. Some people simply held an object while watching the videos, which I thought was quite touching, as it seemed that their aim was to actually establish a bond with the object, aided by the meanings I was trying to convey while sharing my own practice in the videos and reflecting on it in the texts.

People seemed to be calm and feel free to move around and be in the space. From audience reactions after the installation, I got to know that people felt at home in a way, as they found certain images, sounds, and feelings relatable. A sort of longing and mourning was a common feeling, but not necessarily in a negative sense, and more like something they needed to feel in order to remember their own homelands, the things that mattered to them, and to possibly confer a new meaning on them. I was glad that, what seemed to be a very individual practice, ended up opening a space where other stories and contexts of remembrance could intertwine.

***

Plastic is soulless, as most of the times it is used to make disposable stuff. Sometimes no one else but you touch this stuff before it becomes trash. It wasn’t handled, taken care of, by anyone. Used and disposed of. When I touch those other objects, made of clay, esparto, tin, I know that someone else spent lots of time using their hands on them. Caring for them. And they got a soul through this process. And they keep demanding care, now from my hands.

***

Touching an esparto coaster among esparto bushes (Níjar, Spain). Photo by Juan A. Miralles. December 2024

What what happened means (and so keeps happening now)

I hope things will make more sense from a research point of view in this second part of the exposition, after having described the process and outcomes of the artistic practice leading to Esparto, approached.

Conceptual framework

At the moment, the conceptual axis of the research has been narrowed down to three concepts, namely listening, remembrance, and presence. The relationship between these three remains somewhat open to what could happen in the following steps of the project, but it seems to me that these three notions could lead to each other, that is, represent access points to each other (e.g. remembrance could represent an access point to listening, which, at the same time, could be explored as an access point to presence). These are some key ideas that helped me understand each of these concepts, perhaps also in relation to certain situations shown in Esparto, approached:

The work in the field led me to think of practices that had no apparent connection to listening and/or sound(ing) as such (except, obviously, for the practices of making sound or recording sound), such as writing, sitting down on a rock, or touching an old light bulb. At the very beginning of the project, I tried to leave my sonic sensibility apart. I didn’t want my background as a composer to necessarily affect the explorations I was developing. Nevertheless, one can clearly realize that sound ended up being a recurring topic, for instance:

The clock "keeps sounding" even when no one is here, but "does time also keep passing by in here, when there is no one to hear the clock?"

"Time always sounds" and "my memories do sound as well" as, "even when they are mute, I can still hear myself breathing". And in this breathing, "I can still hear the sheep".

And there was the sound of the waves and the breeze, the sound when rubbing the clay jug or touching the esparto strands, the sound of the cowbells and the birdcall, and the sound of other beings, the people working in the quarry, the people driving on the distant road, the bees, birds, and dogs, which announced live among the ruins in many of the clips… As mentioned in the first part of this exposition, sound was always present at the installation, whether we wanted to focus our attention on it or not. Listening may as well be the most pervasive (even invasive) of our senses. I eventually realized that I was clearly working with sound, whether I wanted to or not, and even if I still needed my eyes, hands, or entire body to think about these ideas.

What I decided to believe instead is that listening was just one approach, perhaps my approach, derived from the fact that I do have a stronger sensibility toward sound. Listening is not the only path toward being made present, and listening can be understood in ways that are not reflected here, perhaps because I don’t understand them, perhaps because they haven’t come across (yet). Two ideas about listening led to the decision to consider it as a central notion in this research (and in relationship with the other two concepts):

On the one hand, there is the idea of listening as a continuous process of (re)engagement coming from Jean-Luc Nancy’s thinking. Nancy juxtaposes the notions of hearing and listening as follows: “Entendre, ‘to hear’, also means comprendre, ‘to understand’ […]. If ‘to hear’ is to understand the sense, […] to listen is to be straining toward a possible meaning and consequently one that is not immediately accessible. […] Listening strains toward a present sense beyond sound”(Nancy 2007, 7–8), and concludes: “To be listening is always to be on the edge of meaning” (Nancy 2007, 9). What Nancy favors and what I am dealing with here is the latter notion, that of listening, as listening implies that sense is not fixed, but endlessly open, and that, therefore, one needs to remain open to this happening of sense through listening. This idea of continuity in the unfolding of the world is crucial to understand remembrance as well as a continuous (re)engagement, rather than something dependent on fixed memories. That is, the bonds of meaning and value that remembrance can provide can be established no matter how something remains in one’s time and place (whether as a solid entity or as a trace of it, whether physical or not). Remembrance, thus, could provide an access point to a kind of listening, that is, a kind of openness to the unfoldings of the world, which is furthermore anchored on equally unfolding bonds of meaning and value.

On the other hand, the reciprocity of listening, which necessarily implies being heard, establishes a crucial connection between listening and being present, as presence implies this reciprocity in a similar manner. Nancy also reflects on this idea of reciprocity when talking about resonance: “Resonance is at once that of a body that is sonorous for itself and resonance of sonority in a listening body that, itself, resounds as it listens” (Nancy 2007, 36). This is similar to what Merleau-Ponty reflects on in relation to sight: “The enigma is that my body simultaneously sees and is seen. That which looks at all things can also look at itself and recognize, in what it sees, the ‘other side’ of its power of looking. It sees itself seeing; it touches itself touching” (Merleau-Ponty 1964, 162–163), and it could listen to itself listening. Presence, as highlighted by anthropologist Ernesto de Martino (although in a different philosophical framework), requires the subject and whatever the subject becomes present in relation to (Cimatti 2021, 56), that is, it requires the acknowledgment of presence on both sides, that of the subject and that of the object of presence. This also implies acknowledging the presence of others (and therefore, remembering those others) in the objects of presence, just like my grandpa was present in the old esparto bundle, the milk bottle was present in the kitchen, or the wheat gleaners were present at the threshing ground, if revising some of the moments displayed at the installation.

Remembrance may imply the retrieval of memories that still exist, the (re)imagination of those that are lost, and/or the (re)signification of retrieved or (re)imagined memories. The aspect of (re)signification of memory is crucial to connect remembrance and presence, as we remember through how things remain (are) and not through how things were before. The process of (re)signification (of conferring (new) meanings) is the translation of what we remember and the way we remember according to the context when and where we remember. Remembrance doesn’t just involve a conscious acknowledgment of our lived memories, but also a creative responsibility to (re)imagine those that no longer exist. On top of that, we don’t just remember our memories: memories are shared with us, lent to us, conveyed to us, and so it is not just the objects or places, but us, who become vessels of memory, coming back once more to the reciprocity aspect of these three notions that are being discussed. What listening can imply when related to remembrance, is an active sensory engagement as the main approach to it in the context of this research.

Presence is probably the trickiest concept to be defined at the moment. I have been using this term to simply mean an awareness of the time and place we inhabit, which implies a certain sense of belonging to this time and place. In order to attain this sense of belonging, it is necessary to be able to acknowledge or recognize certain aspects of that time and place as equally present with us, as reciprocally present. That is, we need to be able to establish certain relationships with those aspects of our time and place, so that we feel we belong there. These kinds of relationships were very present in the installation, in a similar manner as when I mentioned before the possibility of recognizing others’ presence in our objects of presence. For instance:

I was present with the almond tree (even if dry) because my mom told me that my family used to harvest almonds in there.

I was present with the sheep in the old barn (even if absent) because I remembered how they used to sound (and I was sounding them out when playing the cowbells in there).

I was present with the esparto bushes because I knew that people from the nearby village used to harvest their strands.

The increasingly faster pace at which things are disposed of and replaced (what I call the age of disposability) might be hindering the capacity to establish these kinds of bonds. But I will delve into this idea in the following subsection. Being made present is being listened to, being remembered, being assigned new meanings and values, being allowed to stay (to remain) while remaining open to further becomings. As Nancy puts it, a “coming into presence” that “we are always moving toward” (Simpson 2009, 2563–2564). These relationships represent a constellation of changing meanings that will continue to (re)shape as the research continues.

Remaining and becoming in the age of disposability

One of the ideas I developed through the field practices was related to how things remain. Things keep being made, withering, and being discarded every time faster (even almost instantaneously), but this can somehow be regarded as a cycle that affords them continuity rather than ephemerality. Remembrance is what offers the opportunity to be aware of this cycle. This idea was reflected in many of the texts of Esparto, approached, for instance:

"[…] And this broken jug will crack even further, and shatter into pieces, and dissolve back into clay. And one day someone might collect that clay and turn it into a new water jug that someone else will remember."

"[…] They [the dead trees] will be swallowed by the mud, and become one with the soil again. Perhaps host a new seed, and start the cycle of simultaneous growth and decay."

"[…] Now, they become wild stones again […]."

"[…] I’ll leave a seed; I’ll grow again; I’m growing and withering at once […]."

And so forth. All I realized then was the fact that remaining and becoming are two sides of the same coin. And that the key to being able to remember is to acknowledge that continuity of the constant change in which we are embedded, within the “poetics of disappearance” (as expressed by Eduardo Nave[6]) we got used to living with, as “waste” paradoxically “continues to frame the horizon of our time” (Hernández 2025, par. 2)[7].

Disposability prevents this continuity, strips reality of value and meaning by denying this continuity, and so, without these bonds (value and meaning), one cannot acknowledge one’s time and place as one’s own, that is, one cannot feel present. The objects, ideas, and relationships that are one-time-use, however, don’t magically go away, but instead end up piled up in a junkyard (whether physical or not), devoid of any meaning. Disposability in our time is reflected, for instance, by Jonathan Crary in Scorched Earth: “[…] Our own disposability is mirrored in our self-defining devices that quickly become useless pieces of digital trash. The very arrangements that supposedly are ‘here to stay’ depend on the ephemerality, disappearance, and forgetting of anything durable or lasting to which there might be shared commitments” (Crary 2022, 9) (such as meanings). He continues: “We are constantly updated about what we must buy and when it must be replaced as it slips into uselessness, and, implicitly, we are cautioned that to hope for anything beyond these cycles of consumption [and disposability] is pointless” (Crary 2022, 53). Edward S. Casey’s words in Remembering about the use of digital means as “prosthetic” memories that can be “easily available, usable, storable, or disposable” (Casey 2000, 43) fit in this scenery of replacement and loss of value. Exploring strategies for making sense of things, for signifying (that is, conferring meaning on) them, such as listening and/or remembering (or listening through remembering, perhaps), subsequently represent a way of resistance against the logics of disposability we are embedded into.

[6] From the title of his exhibition, "Espacio disponible, una poética de la desaparición", 2025: https://www.juntadeandalucia.es/organismos/aaic/servicios/actualidad/noticias/detalle/570439.html (accessed on May 30, 2025).

The continuous cycle of being created and falling apart, however, does exist in spite of being negated by disposability, implying that meanings can equally be continuously restored. Materials such as esparto, clay, or wool keep being used and dissolving back into the soil, waiting to become again. And their subsequent memories are continuously (re)imagined, passed on, and (re)signified. And so, what I eventually understood I was doing through the installation series that Esparto, approached opened was to simply offer situations, spaces in which one could acknowledge this fact again (or anew).

Sensorial autoethnography: a possible (open) frame

A framework is simply a point of reference from which one can understand the “hows and whys” of one’s doings in a research project. Autoethnography came across as a research methodology during the field trips leading to Esparto, approached. The choice of coming back to my homeland was already something linked to my own background, my own story. However, it was rather when I found in esparto grass an even more specific context of remembrance that I realized I was doing autoethnography. This autoethnography is, in addition, sensorial. All ethnographies are sensorial in a way, and so saying this is a bit redundant, but the fact of focusing on listening as an important aspect of my practice evidences this sensoriality.

Sarah Pink’s open definition of ethnography as “a process of creating and representing knowledge or ways of knowing that are based on ethnographers’ own experiences and the ways these intersect with the persons, places, and things encountered during that process” (Pink 2013, 35) seems to already include the aspect of the self (auto-), but at the same time, acknowledges the fact that self-narratives “are of self but not self alone”, as explained by Heewon Chang (2008, 33). In a sense, I am pursuing a sensory way of knowing, even if listening can also be understood here beyond its conventional (physical) meaning. Presence requires a situated approach, that is, an approach that is conscious of its context, which will always imply a certain sense of embodiment, of “tuning-in”, as mentioned before. Sensoriality and presence, therefore, are interdependent. Remembrance is, at the same time, a crucial notion in ethnography, and Pink introduces the concept of sensory memory, which points directly to the possibility of understanding the specific sense of listening as part of the mechanisms leading to remembrance. The (re)signification of memory is something that Pink touches upon when describing sensory memory: “[…] The memories and meanings that might be sensorially invoked are not fixed. Rather […], sensory memory or the mediation on the historical substance of experience is not mere repetition but transformation that brings the past into the present as a natal event” (Pink 2015, 43–44)[8].

Methods such as “stimulated recall” (Pink 2015, 66), used to revisit the documentation of the practice (and, at the same time, to add a new layer of (re)signification to it), or “sensory elicitation”, related to “the use of material objects to elicit responses or evoke memories and areas of knowledge” (Pink 2015, 88) are quite clearly applied in my practice, even if I didn’t know how to refer to them before I got to know Pink’s books. On the other hand, it is important to acknowledge that, as I am no ethnographer, Pink’s ideas are applied here loosely. The kind of knowledge I’m producing (or the kind of ways of knowing or insights on knowing) is still being tacitly defined as the project evolves, and so its frameworks and methods will benefit from the resilience that characterizes artistic research’s “anarchical” nature.

How does Esparto, approached keep happening?

Which means, what comes next? Or rather, what’s becoming at the moment? The artistic process that led to Esparto, approached is now moving toward a further level of engagement that I titled Esparto, embodied, and which will be shared again with the audience in the form of a performative installation in October 2025. In this installation, I am planning on involving the audience’s sensorial approach to remembering a bit further, through something that could be regarded as the most direct means of contact with any object or place, which is touch, and which was already somewhat introduced in Esparto, approached through the esparto objects present in the hall.

Questions such as the sonorous aspect of touch (of listening to the material), the idea that hands carry and create memory, and the use of the hands as a direct source of connection to the world (and therefore, of possible presence in the world) through the intimate relationship established with the material were already posed during the process leading to Esparto, approached. During my next field trip, I will meet up some people from my homeland that still practice esparto braiding and who were willing to introduce me to this handcraft tradition. For the installation, I invited the audience to spend time at the hall performing any handcraft of their choice. I will be there too, crafting with esparto. On the other hand, for Esparto, embodied, I started to work on the method of (re)sonification, which simply represents a method for the (re)signification of/through sound material. A similar approach is mentioned by Pink under the term “soundscape composition” (Pink 2015, 173) or by Vogel when referring to “producing electroacoustic and/or audiovisual pieces with material from the site” (Vogel 2015, 329). In this case, it is being done both through live performance (i.e. the improvisation of two performers over graphic scores that we crafted collaboratively as a sonification of the right-wall video in Esparto, approached) and fixed media (using generative methods to combine field recordings from my field trips). In both cases, listening is prioritized over processes of decision-making for the organization of the materials in time, and thus describing this method as “composing” might be misleading.

In any case, the objective in Esparto, embodied is to create a space to become aware of the temporal and processual nature of the craft, and in which the materials and knowledge collected during my field trips continue to intertwine with the audience’s possible processes of remembrance and presence-making. But the practices leading to this second installation will only become clearer as I step out in the field once more next August 2025. Until then, the stories and reflections that linger from Esparto, approached, continue to interweave the notions of listening, remembrance, and presence while alternative narratives to our disposability are laid out.

Sitting with an olive tree. Olive trees are one of the few trees in the farmhouse that didn't dry up (Abla, Spain). Photo by Juan A. Miralles. December 2024

***

Mona exists because of that moving still image by Dayanita Singh I found at EMMA in April 2025, titled Mona and Myself. I feel that, just by looking at Mona’s image and listening to that background music and breathing, I knew Mona and Mona was there. I didn’t need the story, just a name and some time to stand in front of the projection. But perhaps it wasn’t Mona at all. Perhaps it was Mona through the reminiscences of my grandpa’s radio leaking through the half-closed door of his bedroom during an afternoon nap twenty years back.

***

Esparto, approached was made possible thanks to:

Riikka-Maria Talvitie

Laura Wahlfors

Josué Moreno Prieto

Juan Antonio Miralles Ortega

María del Pilar Castillo García

Francisca and Paco

Eeva Hohti and Mikko Ingman

References

Casey, Edward S. (2000). Remembering: A phenomenological study (2nd edition). Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Chang, Heewon. (2016). Autoethnography as Method. New York, NY: Routledge.

Cimatti, Felice. (2021). “The lure of nothingness. Art and crisis of ‘presence’ in Ernesto De Martino”. Lebenswelt: Aesthetics and Philosophy of Experience, Issue 19: 55–73.

Crary, Jonathan. (2022). Scorched Earth; Beyond the digital age to a post-capitalist world. Brooklyn, NY: Verso Books.

Haroutunian-Gordon, Sophie & Laverty, Megan J. (2024). “Jean-Luc Nancy’s Conception of Listening”. Educational Theory, Vol. 74 (6): 915–941.

Hernández, Isabel. (2025). Exhibition booklet of “Espacio disponible, una poética de la desaparición”, by Eduardo Nave. Centro Andaluz de la Fotografía (Almería, Spain), March 15 to June 15, 2025.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. (1964). The Primacy of Perception. Evaston, IL: Northeastern University Press.

Nancy, Jean-Luc. (2007). Listening, translated by Charlotte Mandell. New York, NY: Fordham University Press.

Pink, Sarah. (2013). Doing Visual Ethnography (3rd edition). London: SAGE.

Pink, Sarah. (2015). Doing Sensory Ethnography (2nd edition). London: SAGE.

Seremetakis, C. Nadia. (1994). “The memory of the senses: historical perception, commensal exchange, and modernity”. L. Taylor (ed.) Visualizing Theory. London: Routledge.

Simpson, Paul. (2009). “’Falling on deaf ears’: a postphenomenology of sonorous presence”. Environmental and Planning A, Vol. 41: 2556–2575.

Vogel, Sabine. (2015). “Tuning-in”. Contemporary Music Review, Vol. 34 (4): 327–334.