|Artaud sought the ineffable with screams and bodies. What if the ineffable were a projected whisper? A shadow that speaks for you?|

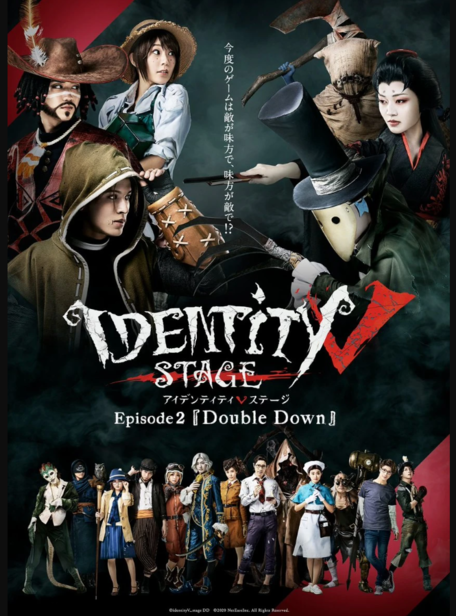

In recent years, particularly in Eastern contexts such as China and Japan, digital games like Identity V have shown a remarkable phenomenon: players develop such intense emotional and narrative attachment to the characters that these digital beings are later brought to life in full-fledged theatrical performances. The phenomenon is more than simple adaptation — it is the ritual elevation of a character from a screen-bound existence to a physical, shared, collective experience.

This chapter explores the idea that a videogame demo can serve as the birthplace of a character cult. By allowing the audience to engage directly, emotionally, and individually with a character through interaction, discovery, and personal choice, the game functions as the mythological 'origin story'. The theatre then becomes the temple — a space where the myth is retold, expanded, and ritualized in a collective setting.

In this project, the videogame I intend to create is not merely a promotional tool or narrative sketch. It is a manifesto in playable form, a vector of empathy and projection. The demo introduces the character (the protagonist, a psychopathic gazza ladra), offers glimpses of the world, and cultivates a mystery — a tension that cannot be resolved inside the demo. This tension creates a desire to see more, to know more. It creates longing.

In fan-made RPG horror games (Omori, Ib, Mad Father, etc.), the character is rarely powerful. They are broken, elusive, contradictory. This is exactly what makes them cult-worthy. The player wants to understand them or even just be near them again. When the narrative ends or the game is short, that desire does not disappear — it transforms into fan art, discussions, theories, and eventually, into the desire for performance.

I intend to replicate this process consciously: to use the game demo as a tool to create cult-status for a character, and then to stage that character in a theatrical ritual that feels like the fulfilment of a prophecy — the reunion with a lost, beloved presence. This experiment can be repeated: the game as initiator, the theatre as responder.

In this sense, the game is no longer just an entertainment product — it is a myth-generator, a modern epic. And the theatre becomes the only place where that myth can be fully embodied, confronted, and re-imagined.

This chapter will also include references to:

- Identity V and its theatrical extensions

- Mechanics of character affection and emotional imprint in indie games

- The structural pattern of "demo → cult → ritual"

- Possibilities for repetition and sustainability of the model

In conclusion, this hybrid approach aims to redefine the promotional as the poetic. The game is not a trailer — it is a threshold. And once crossed, the theatre becomes a sacred space where the echo of that threshold returns as revelation.

Introduction

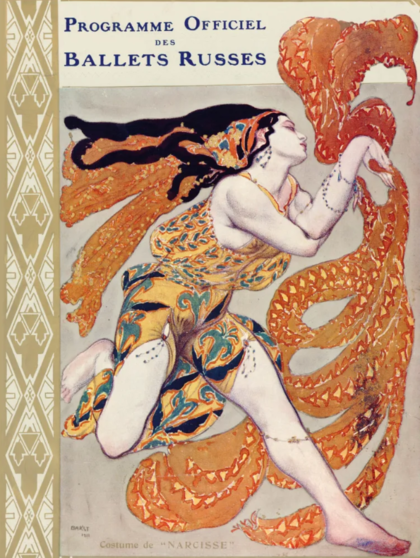

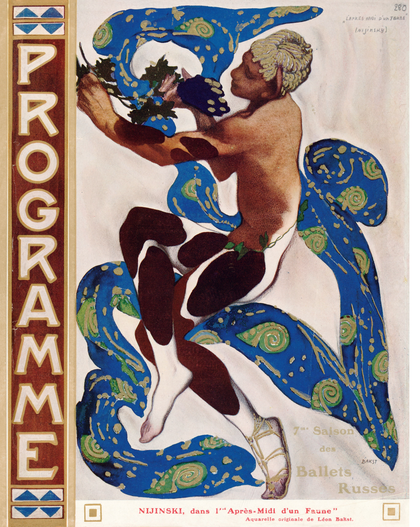

This research explores the foundations of a new kind of theatre – a Theatre of Terror – where fear is not a genre, but a ritual. In this theatre, the character, the costume, and the monster are not separate elements, but three expressions of the same psychic body.

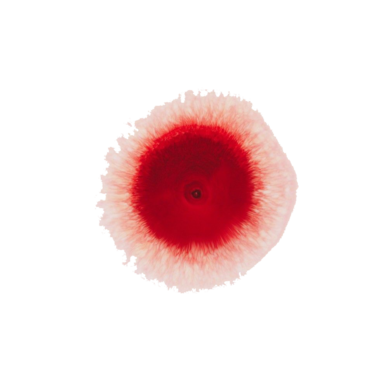

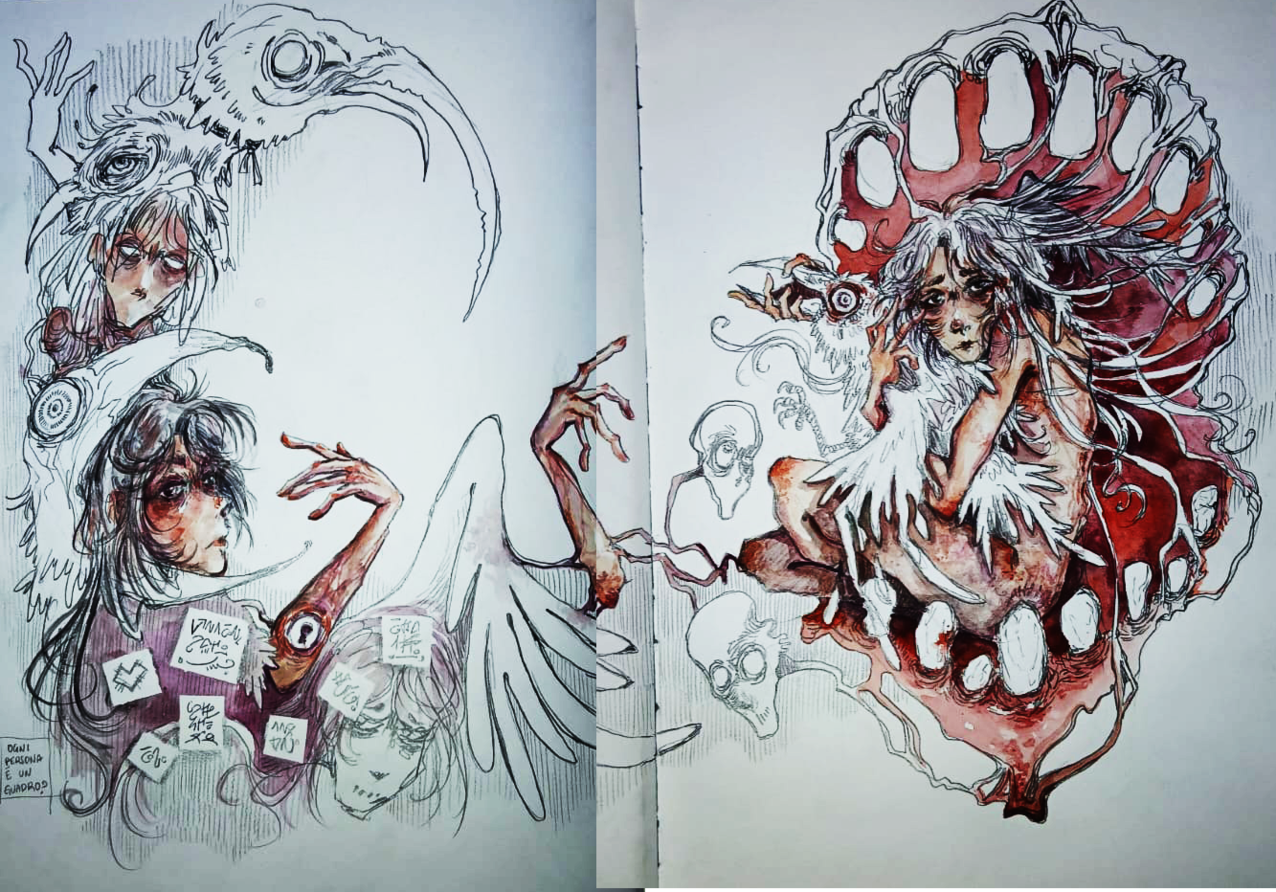

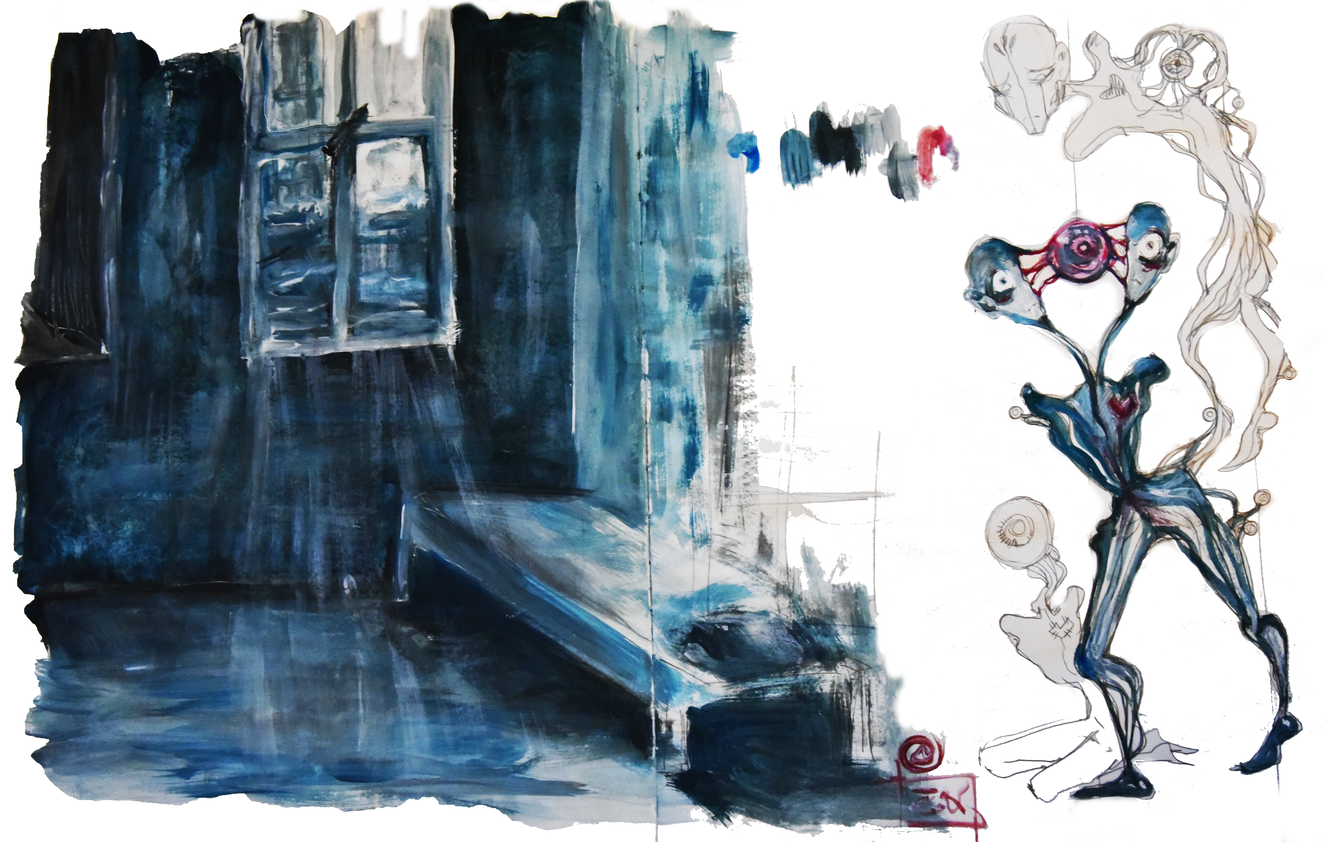

The work develops through a series of visual, performative and theoretical investigations. I begin with sketches drawn from life, observing faces and imagining their inner creatures. From this, I build symbolic monsters and propose a visual anatomy of fear. These monsters become theatrical entities, accompanied by evolving costumes and narrative fragments.

The research is grounded in a practice of collection and transformation: petals, feathers, insects, and natural objects are gathered and preserved, not for decoration, but as emotional matter — visual metaphors of trauma, memory, and the hidden self. Each material holds a story. Each costume is a mask and a wound.

One core question guides this work: what do we hide when we present ourselves? And what emerges when we stop pretending? This tension generates a space where monsters can speak, costumes can lie, and characters can become rituals.

I also experiment with interactive formats, including a videogame demo that serves as a playable prologue to the stage performance. The player builds an emotional bond with the character — a bond that is then transformed, ruptured, or deepened in the theatre. This structure draws from cult mechanics found in horror RPGs and fan-made narrative games, where characters become iconic not because they are explained, but because they are incomplete.

This project combines performance, visual art, costume design, digital experimentation and dramaturgy.

Its ultimate aim is to restore theatre not as a spectacle, but as a necessary ritual: not political, nor didactic, but deeply human.

The Theater of Terror –

Anatomy of the Monster, the Character, and the Costume through Digital and Scenic Rite

| The costume doesn't embellish. The costume lies. The costume is stage skin. And when it tears, the monster appears |

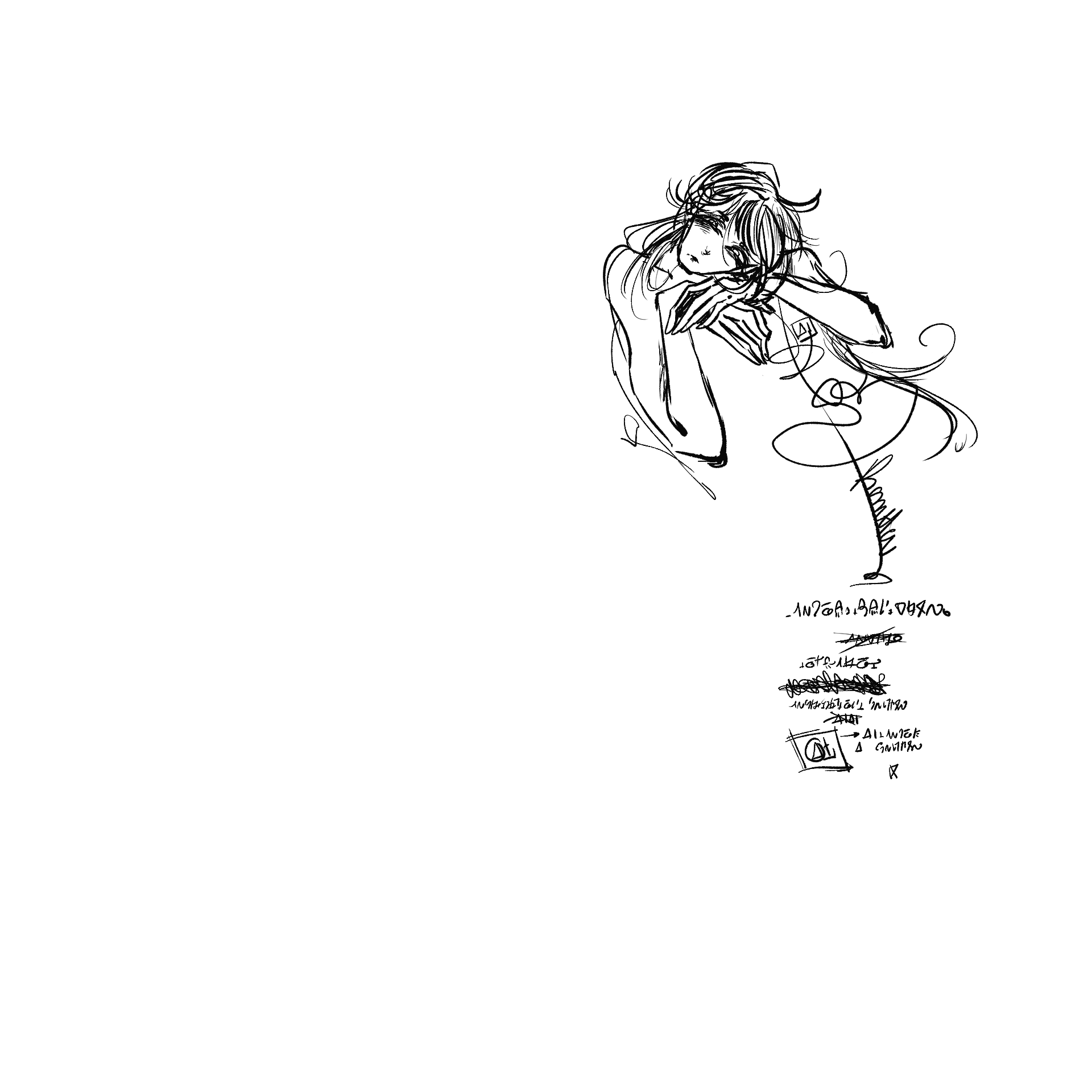

One of the central methods in this research is an intimate visual exercise: I begin by sketching a person — a classmate, a professor, a stranger. Not a portrait for others to recognize, but a personal act of observation. I copy them from life, attentively, and then I close the reference and begin to ask: “What monster hides behind this face?”

I imagine an interior presence: a creature built not from horror tropes, but from symbols, colors, movements, obsessions. Sometimes I know something about the person; sometimes I invent. But in both cases, the monster becomes a kind of emotional self-portrait of how I perceive them — or how they refuse to be perceived.

This process leads to a third step: the costume. If the monster is the truth and the face is the mask, then what is the costume?

I have come to see it as the lie the character chooses: the part of them they want others to believe.

In this sense, the costume is not decorative, but ideological. It is the visible shape of a psychological strategy. Eventually, all three layers — face, monster, costume — come together in a final drawing. These compositions contain text, anatomical notes, symbols, and narrative hints. They are not just illustrations. They are acts of interpretation.

An important aspect of this method comes from a personal trait: I have face blindness (prosopagnosia). I often fail to recognize people’s faces — even people I know well.

This limitation has taught me to identify people through other elements: voice, movement, presence, detail. In a way, this condition has shaped the whole project: I don't draw people to remember them — I draw them to invent a different way of knowing them. The monster is not their hidden self. It is my attempt to see them, beyond what I can recognize.

Monsters in the Mirror:

-

Drawing What Cannot Be Seen through copying from life, transcription of observation and fabric.

In my research, the costume is never just clothing. It is a surface of narrative, a layer of fiction that the character builds to interact with the world — or to hide from it. Conversely, the monster is not an enemy, but a shadow of the character’s interiority. The costume is what the character wants us to see; the monster is what the character cannot hide when the light is low enough. Both are essential to the anatomy of the role.

To investigate this relationship visually, I have been training myself to draw on transparent sheets (lucidi). This technique allows me to separate and overlap elements: one layer for the human character, one for the costume, and one for the monster. Drawing in transparency reflects the conceptual transparency I seek in the performance: not to explain a character, but to reveal its fractures.

The costume, in this framework, is a deliberate act of storytelling. It may protect or lie. It can be delicate, flamboyant, orderly, or stiff. It tells us what the character wants to project — their aspiration, their control, or their false safety. The monster, on the other hand, is uncontrollable. It emerges through color, gesture, asymmetry, through lines that do not follow logic but impulse. It exposes the character's raw, symbolic self.

This process leads me to develop paired designs, in which monster and costume are treated not as opposites, but as two voices of the same being. The monster may inform the texture of the costume — for instance, a trembling movement in the monster’s form may become pleated or fragmented fabric in the costume. Conversely, the restraint of a costume may highlight the violence or fluidity of the monster.

Ultimately, the goal is not aesthetic harmony, but psychological coherence. Every character must bear within their costume the lie they tell, and within their monster the truth they try to silence. The use of transparent drawing supports this: it is a method of uncovering — not what is visible, but what visibility tries to conceal.

In the final costume study, these layers are brought together: the actor may wear the costume, but the monster may be projected or moved around them. The space between costume and monster is the theatrical void — where fear, interpretation, and imagination dwell.

Monsters do not emerge from the surface. They come from beneath — from what is buried, repressed, obscured. In this chapter, I explore how the figure of the monster is central to my idea of a new form of theatre: a theatre not built on narrative or morality, but on excavation — of emotion, of psyche, of memory. This is what I call the art of the underground.

This concept was first developed in my previous thesis The Underground of Art, where I examined how the invisible, the hidden, and the uncomfortable become engines for creation. I argued that the artist must descend, must dig into the layers of the self and society, to bring forth the fragments that still burn in the dark. The monster is the figure that emerges when we succeed in that descent.

A monster, in my framework, is not a villain or an enemy. It is a symbol of inner truth — a distorted but sincere expression of what a character refuses to face, or cannot articulate. Each monster is different because it is shaped by the soul it belongs to. It is a psychic fingerprint.

This is why, in my research process, I practice drawing from life: I observe people, copy their faces, then imagine and draw the monster that would belong to them. Sometimes this is based on what I know (a friend), sometimes on what I sense (a stranger). The monster is built from color, line, instinct, and metaphor. This exercise is not decorative — it is anatomical. A reverse anatomy of the self.

From this logic, I build characters whose monsters are not external enemies, but choruses of the inner self. In my theatre, the monster may even speak the lines the character cannot. It may take the form of a projection, a shadow, a moving sculpture, or a coded presence that responds to the actor’s actions. Costume, character and monster are not separate. They are layers of the same being.

The art of the underground means that beauty is no longer light. Beauty is what we find despite the dark — or because of it. It is born from pain, from fear, from memory, from the raw material of what we hide. The monster is not there to frighten the audience. It is there to reveal the shape of what frightens them already.

This theatrical logic echoes mythological and folkloric traditions where creatures often represent vices, sins, secrets, or cosmic truths. But my approach refuses allegory in favor of embodied affect: the monster must be felt, not decoded.

The monster becomes a bridge. Between actor and audience. Between the self and what lies beneath. Between fear and beauty. Between the unspoken and the uncontainable. That is the art of the underground.