Arthur Faraco, Brazilian double bass player, teacher and researcher, in his PhD, 'Comprovisation: Between Composition and Improvisation in the Emergence of Contemporary Musical Practice' identifies two main perspectives on comprovisation within existing theories:

The first perspective emphasizes the use of audio editing and processing technologies as essential for understanding and advancing the relationship between improvisation and composition. Tools such as audio editing software and digital processing patches offer new musical possibilities, helping to balance these creative processes. For example, Michael Hannan, an Australian composer, keyboardist, and musicologist uses comprovisation (2006) to create compositions by recording improvisations, which are then refined and structured through editing tools.

Julius Fujak, Slovakian experimental composer, comproviser and multi-instrumentalist, in his book 'Various Comprovisations: Texts on Music (and) Semiotics', leaves this trichotomy confrontation to emphasize the fluidity between composition and improvisation, and the need for the term comprovisation ''as an artistic practice that exhibits transversality (in its methods), where planned outcomes (which may or may not occur) and unpredictable changes coexist, requiring a creative and operational response''4.

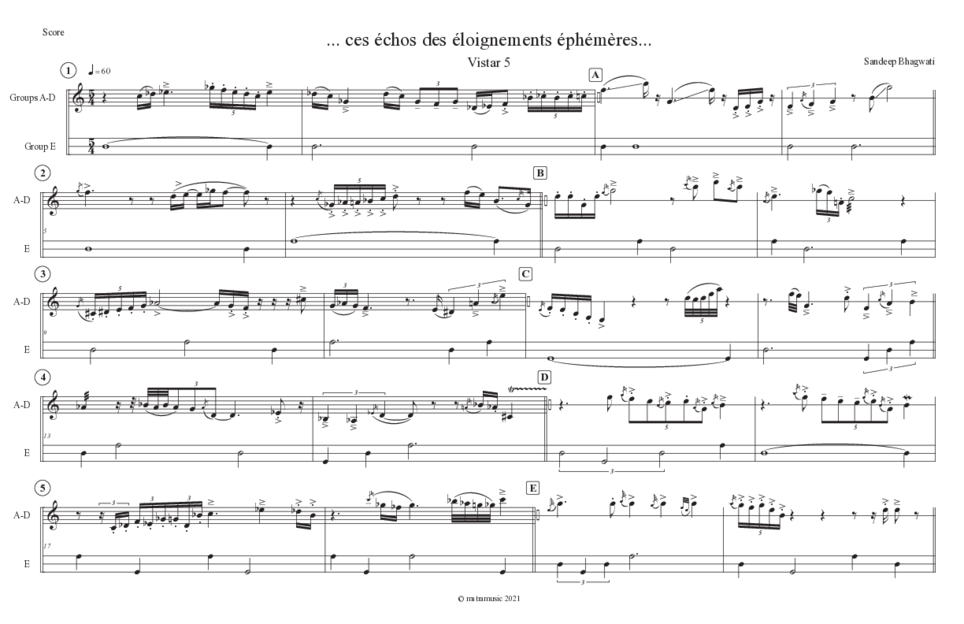

I would like to highlight the work by Sandeep Bhagwati, Indian poet, teacher, researcher, media artist, conductor stage director and theatre director, and his notational perspective5 because it provides a clear vision of this second theoretical strand exploring the continuity between composition and improvisation through new approaches to notation, a concept to which I feel strongly connected, as it closely aligns with my own explorations in this area as we'll see later through two of my pieces as examples, Leave The Door Open and Traffic is the new Silence.

To describe the diversity of musicking6 practices that lie between the extremes (the fully composed versus free improvisation), the term notational perspective is proposed as a more globally applicable concept. It reflects the varying degrees and varying alternative ways to which music can be notated, from fully written scores to largely improvised forms, from traditional notation to Symbolic notation -which places symbols on a musical stave to represent pitch and time, though it doesn't fully capture temporal dimensions-, Graphic notation -cartesian representation of sonic space, ideal for continuous, non-discrete changes like slides- or Verbal scores -either extensions of symbolic notation or literary descriptions, describe actions, moods, or interactions between musicians-.

According to Bhagwati, any musical live performance could involve, in a certain amount, two types of elements: context-independent elements and context-dependent elements. Context-independent elements are those that remain constant across different performances, such as the notated score or the fixed parameters of a composition. These elements are not influenced by specific situations, are repeatable, and define what we refer to as an "artistic work" or a "composition." In contrast, context-dependent elements are the contingent, spontaneous aspects of a performance that are realized at the moment. These elements depend on factors like ''chance procedure'', playing it ''by ear'', inspiration, arrangement, improvisation or interpretation, encompassing a broad spectrum of creative and situational dynamics.

Bhagwati's insight is that while regular musical notation functions as a tool to establish context-independent parameters (such as pitch or rhythm), it cannot fully capture everything that happens in a live performance. Traditional notation, according to Bhagwati, is limited in its ability to represent the contingent, momentary aspects of music-making, such as the nuances of expression, interpretation, and improvisation. This "notational bias" often leads to a situation where elements of music that are difficult to notate—such as improvisation or chance—are undervalued or ignored in Western traditions. Comprovisation is an attempt to reconcile these two aspects of music, suggesting that most musical performances exist on a continuum between the pre-determined structure of the composition and the spontaneous, context-dependent nature of improvisation. The boundaries between these two poles are not fixed or rigid, and the reality of music-making often involves a complex interplay between both.

The term comprovisation, a relatively recent addition to the literature1 does not yet have a universally accepted definition. One of the first uses of the term 'comprovisation' seems to have been associated with trombonist Paul Rutherford in the 1970s. In his work with the group Iskra 1903 (alongside guitarist Derek Bailey and bassist Barry Guy), Rutherford described his creative process as compositional, giving the musicians a certain degree of freedom to replace written sections with new, improvised ideas. Comprovisation combines the concepts of "composition" and "improvisation" to describe a creative practice that merges both elements in musical performance. This concept challenges the traditional dichotomy between composition (a pre-planned, fixed score or text) and improvisation (a spontaneous, contingent act of performance) offering a more nuanced understanding of how these two practices coexist and influence one another, while also introducing a new set of notational tools to make this fusion possible.

As discussed in the previous chapter, contemporary musical practices—emerging in the 20th century through innovations shaped by the avant-garde art movement—laid the foundation for comprovisational practice. Thus, in America, the concept of indeterminacy, where elements of a specific composition are left to chance or performer interpretation, laid the foundation for comprovisation with its earliest expressions appeared in the works of Charles Ives (1874–1954) and Henry Cowell (1897–1965) and later evolving through the New York School, with John Cage as its central figure. In Europe, the first term connecting composition and improvisation was aleatoric music, largely popularized by Pierre Boulez (1925–2016).

Since the mid-20th century, various terms, besides Comprovisation, have been coined to describe specific musical practices embodying this fusion, including "intuitive music" (Für kommende Zeiten, Karlheinz Stockhausen, 1968–70), "game pieces" (John Zorn, 1984), "conduction" (Butch Morris, 1985), "limited aleatorism" (Trois poèmes d’Henri Michaux, Witold Lutosławski, 1961–63), and "structured improvisation" (Because a circle is not enough: music for bowed string instruments, Malcolm Goldstein, 2022). While these terms effectively describe distinct creative methods, they often remain associated with specific figures or movements and serving to distinguish these practices from the dominant score-based tradition in Western music.

Originally emerging as a practical neologism, comprovisation has evolved into a conceptual framework for understanding specific artistic approaches. In this sense, it exists within a continuum of musical practices that blend fixed and contingent elements2, aiming to balance compositional and improvisational processes.

The second perspective characterizes comprovisation as a broader term for contemporary musical practices that provide 'open' space for improvisation by using different kinds of musical notation so that the amount of fixed composition is well balanced with significant performer involvement, spontaneity and flexibility. In his thesis, What is comprovisation (2008) Michael Dale, American composer-improviser and multi-instrumentalist, explains how comprovisation differs from composition and improvisation, both in definition and in their characteristics of identity and variability3.

In my own comprovisational pieces, which we will discuss later, I have explored various tools and approaches, experimenting with different ways of notating that allow the constant-independent elements of the compositions to be framed. However, my ultimate goal aligns with Bhagwati’s notion of comprovisation—seeking the “unforeseen” that emerges in the concert situative, shaped by the space, time, and presence of listeners. In this process, the unexpected intertwines with the expected—the fixed and determined aspects of the “work”—at the moment of performance. Musicians operate within a dynamic field of tension: on one hand, experiencing freedom due to the unfixedness of the material, and on the other, remaining connected to the structured process of rehearsal. This paradox—between freedom and fixedness, openness and boundaries, discovery and repetition—is central to how comprovisation is realized in practice7.

-

Composition: one person determines as much as possible what a piece of music will be (notwithstanding the variability of the performer's style & performance, also acoustic/atmosphere/audience/event).

-

Comprovisation: one or more people determine only part of what a piece of music will be; the rest is determined at the moment of performance or execution.

-

Improvisation (pure or complete): one or more people determine nothing in advance of what a piece of music will be; it is determined at the moment of performance or execution (notwithstanding the predetermination of individual conditioning and experience, both cultural and psychological).

From these definitions, Dale makes these corresponding characteristics of identity and variability:

-

Composition: can be repeated exactly (notwithstanding variations in interpretation: e.g. rubato, tempo, etc.) and retain a recognizable identity.

-

Comprovisation: can be repeated with more or less variability and retain a recognizable identity.

-

Improvisation (pure or complete): cannot be repeated exactly; recognizable identity ('as if seen before') can only occur by chance or through repetition inherent in a particular performer's stylistic identity and technical ability.