AURORA PROJECT – RESEARCH ENQUIRY

The Aurora project is the first public manifestation of experimental research fromSensing Remoteness, a recently formed interdisciplinary group that brings together researchers from across Northumbria and Newcastle Universities in the North East of the UK. Members of the group come variously from The Cultural Negotiation of Science (CNoS) group and the Space Interdisciplinary Research Theme (IDRT) at Northumbria University as well as from the current UKRI-supported project Sonic Intangibles project based at Northumbria and Newcastle University.

One of the principal areas of enquiry that established the group was to consider the relationship between ‘Remote Sensing’, as a technical mode of data gathering, established and employed across multiple techno-scientific fields, and ‘Sensing Remoteness’ – an idea that necessitates a wider philosophical, creative, critical and ethical enquiry of the relationship between technology and the sensing human (and more-than-human) being.

Current members who have contributed to Sensing Remoteness generally and the Aurora project specifically are: Patrick Antolin (Plasma Physics), Jorge Boehringer (Sound Art/Sonic Intangibles), Fiona Crisp (Arts/CNoS), Timothy Duckenfield (Plasma Physics), Luis Guzmán (CNoS/Space IDRT), Daniel Ratliff (Mathematics/Sonic Intangibles), Paul Vickers (Computer Science/Sonic Intangibles), Clare Watt (Space Weather/Plasma Physics) and Steph Yardley (Plasma Physics).

Below are some of the questions – and responses – that we set out with:

· Fiona: Big data and remote environments

How can artists, scientists and technologists help lay-publics experience, connect to, and care about big data and remote environments?

Patrick: There are many ways to describe something in nature. For instance, one can use poetry, mathematics and physics. Through the arts we access ways to describe what we see that connect with emotions, experiences and our human nature. On the other hand, maths and physics language use objectivity to describe an object or event, so that it can be generalised out of the human experience. Hence, both ways of approaching nature are complementary. There is not one “true” way because the concept of understanding may mean something different to different people.

Tim: One of the most significant stumbling blocks we must overcome is preconception. The average lay-person already has a preconceived notion of what a space scientist does, their mannerisms, what they look like (c.f. NASA films like Apollo 13). Similarly, there are preconceived notions of science educators, composers, artists etc. I strongly suspect when anybody wanders to our exhibition, they are expecting a Brian Cox narration of glitzy animations of space (aside: The Planets on BBC is very interesting!) People do not generally have much experience with the near-Earth environment, or how one extracts information from remote sensing data. I think we should lean into this lack of knowledge, since it mirrors the research aspect of probing the unknown! We should try and avoid well-worn tropes, aim at stimulating curiosity and surprise.

· Fiona: Concept and experience.

Can the environmental-socio-ethical intersections of big data and remote environments be experienced as a sensorium by audience-participants?

Patrick: By definition, sensorium is anything linked / that can be linked to our senses. It is possible to compare remote things with things in everyday life. The use of metaphors or similes with events / objects that we are familiar can greatly help towards achieving an understanding. Then, one can take those familiar events and elevate them using visual, hearing, touching to achieve another layer that detaches from the real-world object / event one started from.

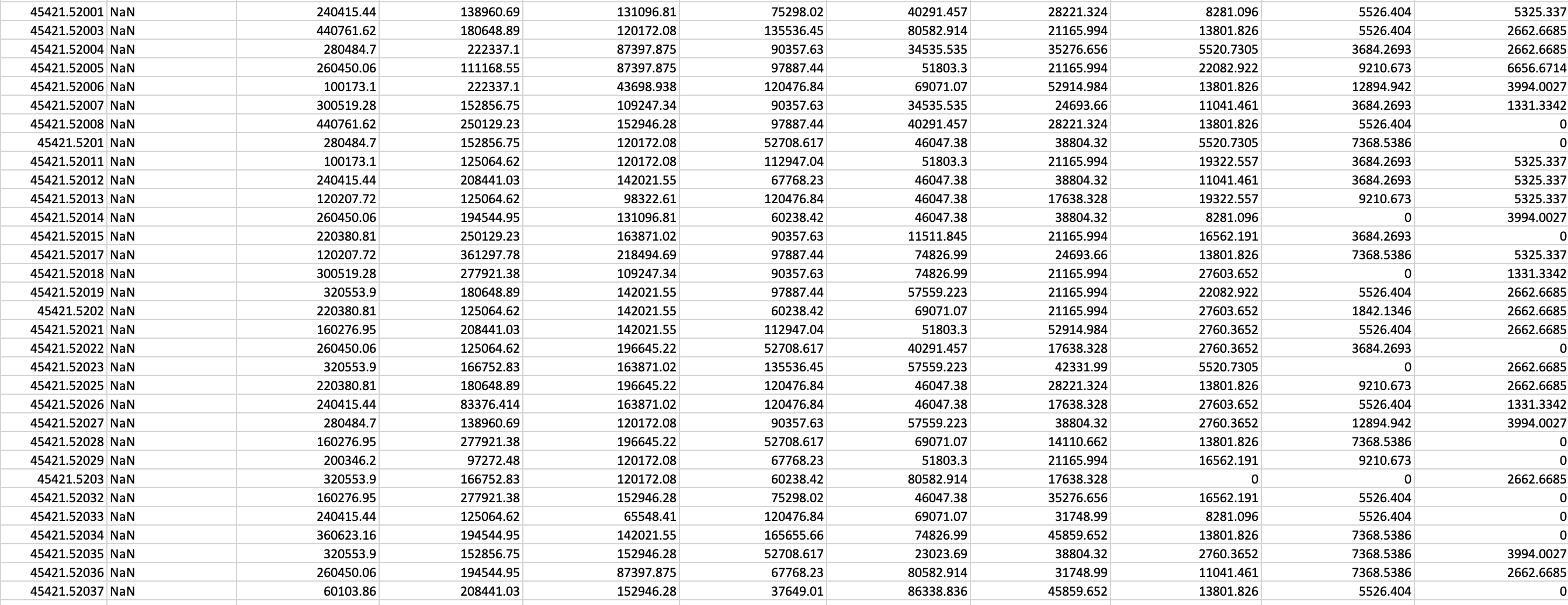

Tim: I think one of the easiest ways of tying remote sensing (traditionally a computation-heavy, emotionless field) to social interactions is through reference to the recent gatherings to watch the aurora. Nearly everybody I speak to about this has talked about sharing photos; finding from the news when there will be a visible auroral event; going out late at night to a nearby hill and finding many people already there, etc. It would be good to highlight that this echoes the fact that remote sensing tends to be a collaborative field as well – e.g. our geomagnetic indices are calculated through comparing many stations across many countries. This has issues too – I remember a talk where political divides (warzones, lack of maintenance funding) make a quantifiable difference on the quality of the geomagnetic data. With regards to the sensorium, I think some way of including recognisable references to these aurora + the community (time series of #aurora uploads? Photo reel of amateur photos?) is a good idea.

· Fiona: The ‘nature’ of data.

Does the ‘nature’ of data – including how it has been synthesised/constructed/augmented/translated – affect the ethics of how it is used?

Paul: I would look at this more in terms of the ethics of the mapping choices: what are the ethical issues of how we choose to represent the data in sound? What impact does this have on the listener?

Patrick: Perhaps the only realm in which ethics is not involved is in the pure objective description of an object or event. This can be achieved in mathematics but even in physics an experiment is never purely detached from the observer. Hence, there is always a modification of the object. The ethical question becomes very relevant when one adds an emotional component when describing an event, such as a background song when showing a video.

Tim: I suggested we “terrify” listeners with sudden amplitude changes and eerie long stretches of near-silence! This is very extreme in its agenda (highlighting the violence of space to which we are sheltered to by lack of sensing + magnetosphere), but we have already discussed how any form of the data will have an agenda to some extent. I am reminded of the first time I heard the sonification of Juno crossing into Jupiter’s bow shock, it sounded so alien and terrifying even without knowing the physics. I appreciate this is overtly manipulative, but I think we should be trying to play on the listener’s emotions and upend preconceived notions about remote sensing + big data!

· Fiona: Sound and representation

How can sound, rather than visual representations, help us understand remote and/or extreme environments? Can they make the “abstract” notion of these areas/scenarios approachable/tangible? How “representative/truthful” might these be?

Paul: Further, in what ways does sound bring us into relationship (or affect an existing relationship) with these intangible phenomena?

Patrick: sound, as opposed to visuals, is much more connected to our emotions. This does not mean however that one cannot better explain an event with sound. It is just more difficult to be objective. Although our eye is much more developed than our ears (in terms of capturing information), we are more sensitive to sound than the visuals because we are less “loaded” by sounds than images (e.g. there are many sounds that people cannot stand, but we have become quite insensitive to images). This difference can be used to better detect anomalies in data (which are often important) or understand certain distributions of data in a faster way than with just images.

· Dan: Interdisciplinary Working

Can the thoughts and ideas we develop in the crucible of our discussion change how we ask questions about the natural world/science?

Paul: In what ways do these discussions, and the eventual ‘product’/artefact cause to ask questions about how we do things in our home disciplines?

· Dan: Sensoria and New Knowledge

Rather than interpretation of data/ideas, can the sensoria we help to manifest be used for discovery/new truths/perspectives of objects/phenomena?

Patrick: This is something that can easily clash with how science works nowadays. We are used to being objective in science, but the usage of sound may introduce ways of discovery that are not directly objective. Perhaps it is just a matter of getting used to. So sound is mostly a tool for discovery but may not be accepted as proof for that discovery.

Tim: I see no reason why the sensoria/sonification cannot help discover new phenomena. The great thing about discoveries is that we often do not know exactly what we are looking for until after we found it! Hence, we should always aim to look at data with different perspectives/contexts/scaling/groupings etc. The process of converting our data into something suitable for the sensoria will illuminate some aspects and hide others, compared to standard visual analysis, which is what we want! One issue I can see is that understanding the context of the sounds will take time to develop (e.g. being able to distinguish from the expected changes from daytime/nighttime cycle), and this time may exceed the duration of the sensorium.

· Dan: Sonification and New Knowledge

Can sonification enhance research in the field of astrophysics?

Can sonification help publics understand the physics of space?

· Patrick: sonification can help add layers of data without overwhelming the visual component. Often in astrophysics we use images of different wavelengths and the comparison between these images conveys physical processes. The usage of sonification is perhaps much more direct when describing periodic phenomena such as waves in space. Signals that are in phase / out of phase can be far easier to detect through sound than by just looking at their temporal representation.

Waves in space behave very differently than on Earth. For example, they are anisotropic. This aspect can be represented to some extent with soundscapes such as those generated by IKO.

Sonification can also greatly help understand and detect physical processes such as Doppler shifts.

Tim: I agree completely with Patrick, and want to highlight the advantage of combining multiple data sources simultaneously.

· Jorge: Sound and Scale

Sound can occupy vast scales between the intimate and the deeply spatial. How can this flexibility of scale in sonic phenomena act as a means of bringing the remote or intangible into proximity and textural experience?

· Tim: One important distinction between our hearing + vision is how much easier it is to interpret scale with our hearing, being logarithmic. We innately understand larger scales from the low frequencies, and small scales from high frequencies. Since our data can cross many orders of magnitude, this is an advantage. Furthermore, the link between music + emotion is strong. Finally, by combining sound + vision can make our experience more immersive – after all we are using remote sensing to explore a real space (the near-Earth space environment), just in a way our bodies are not able to.

· Jorge: Plasticity of Sound

Can the plasticity of sound be used to ‘take impressions’ from remote phenomena, or be rubbed up against them, to later listen to what traces of the phenomena are left in the sound?

· Tim: It would be interesting when we get to the “nitty gritty” of sonifying the near-Earth space data, exactly what levers we have to play with. Each dataset has MANY parameters, and we could play around with combining different dataset parameters with different sound parameters to see the effect. I am not experienced enough with sonification/music theory to have a good understanding yet.

· Jorge: Experiences of Listening

How do experiences of listening, and indeed of making sound, allow for meaning to arise from vibration across distance?

Paul: And how can we assess/evaluate the perceived meanings that do arise? (They could be completely false.)

What sorts of meanings from vibration can be sensed between people? and how are these the same or different to those that can be sensed between species, life-forms, states of matter, or other energetic forces in close proximity or across distances in space and time?

Tim: Can we make a sound loud/low enough to resonate in a listener’s chest/body?

· Luis: Data Embodiment

How can we use space technology to uncover new experience.

Paul: Embodiment, for me, is about how the whole body (or even person) is implicated in the experiencing of the data. This takes us beyond pure cognition and the Cartesian mind-body dualism.

Tim: we should highlight the fact that our body is not capable of sensing magnetic fields, electric charge, nonthermal distributions whereas these are crucial to understanding space. Note some animals can sense magnetic field! Our telescopes + satellites are our eyes and ears/hands. This is what makes space so alien in a way, the fact that all this activity is happening which we cannot sense. It reminds me of Project Hail Mary, in which one group of aliens have lived their entire civilization’s life span within a magnetosphere so they never needed to learn about space weather. During the book events they die mysteriously from a scary, unknown force (radiation) which they had no instruments to sense – terrifying!

· Luis: Technoplasticity

Plastic exploration of space technology, what material and conceptual aspects of technology can be directed towards the augmentation of the experience to –in Heideggerian terms -¨bring the Being into the open¨

· Luis: Materialist ontology

Matter comes from the stars. The matter that composes the Earth and our own bodies was created in a massive star. Even though the Sun is not massive enough to create the matter of our planet, the radiation it emits is essential for the development of the conditions that make life possible. In other words, sunlight animates the world.