A covnersation about mapping - with DR Yaara Rosner Manor ( Urban planing)

How would you define mapping? What elements are part of creating a map?

“A map is always the creation of an abstract representation that corresponds to whatever interests you. A map is an answer to a specific question, or to a set of questions, within a particular field. In mapping, we feed data—organized by parameters—into a representation of physical space. For example, if we want to map movement, we add movement data as a layer on top of the base map of the area we’re mapping.”

So a map is always just a representation of something?

“In planning we’re aware that when we use a map we’re confined within a certain idea, and sometimes, in order to reconnect with the physical space, we actually need to blur that idea. For instance, we might sample data randomly, or we might work with more than one map at the same time in order to intentionally dismantle the system.”

What are the practical tools used in the field for mapping?

“First of all, there’s measurement. In the past people measured using ropes, and today measurement is mostly digital—often using laser beams. In addition, field surveys are used a lot. For example, for a map of plant diversity, a person will walk through the area throughout the seasons and survey the data that will be added to the map. It’s the same with urban data: if you want to map businesses, someone must physically document the number of businesses, their locations, or any other relevant information depending on what you’re trying to examine.

Interviews are also a well-known practice. And within mapping there are practices that actually change reality. For example, when hikers create trail markings along the route that’s easiest to walk—other hikers follow those marks, and in that way the route gets established through the practice of walking.”

Maps are used as representations of information.

The information is simplified and organized in a way that is readable.

The “real-time city,” however, is not readable and cannot be organized.

In this research, I aim to map, but not to create a “map.”

The mapping exists in the process of mapping because only then is it in “real time.”

Movement cannot be “represented” like a drawing—it doesn’t last and leaves no trace. The movement itself is the mapping; it should not create a map, because a map is just a representation of what is happening.

Mapping elements, however, can still be applied—such as measurement and the use of relationality. Using the elements existing in the space to generate knowledge, the knowledge generated should also exist in the here and now.

Experiment 1 – Responding to Directions

(Arnhem)

In this experiment, I was interested in embodying a very physical element of the here and now of the urban space—directions. Through the score, I asked the dancer to respond to these directions in a physical way. We tried this in different urban environments.

Score:

Stand in place and observe your surroundings. What directions can you see? What directions can you feel or notice?

Which directions make you move? In what way?

Lean into the directions.

How many directions can you follow at the same time? With which body parts?

Let it overwhelm you.

Are the directions taking you, or are you following them?

Can you follow the directions from inside your body? Can you follow with the outside? What is the difference?

Dancer: Eva Pletikosić

Eva’s Thoughts – Location 2

It’s very different with human-made things than with nature.

It’s easier with human-made things because the directions are clearer—clearer for the eye, and the movement itself is easier to read.

It’s very interesting to notice the layers of the environment—sometimes I can take something from far away because the movement there is clearer.

With cars, it’s very clear—they take me. People move much slower, so I have to take from them.

Am I showing the directions, or am I going there with my body?

Eva’s Thoughts – Location 1

-

It was nice to first observe for a bit—then things felt familiar when I started moving.

-

It’s very easy to follow the directions of moving things.

-

It helps you get into the flow.

-

I had to be aware of my whole body, because following moving things is easier with the hands and head.

-

Following static things feels easier with the whole body.

-

Not just seeing what is there, but also seeing what could already move you.

In the beginning, everything was so exciting. At some point, the act of following the obvious things became the base—and from there, I could start following things that were further away, in the background, or less obvious.

When the moving directions became the base, I was also able to follow static directions.

Following sound felt a little overwhelming, but it also added another layer. Maybe it could be introduced later in the score.

Eva’s Thoughts – Location 3

-

This location was fun. I prefer very busy environments much more than ones that don’t have enough going on—this location worked much better than the second one.

-

“Let it overwhelm you” really opened things up for me. I was able to move out of my head and into my body.

-

Because there were so many directions (human-made), it didn’t give a clear front—it felt like 360 degrees for me.

-

There was a nice balance between repetitive elements and changing ones. When there are repetitive things in the space, they can just live in the body, and then other elements can enter on a different level.

-

Following directions from the inside was an interesting instruction—it gave a different quality to my movement.

Scores for Experiment 2

Dancer: Ariela Ben Dov

Tel Aviv, 3.11.25

1: Introduction:

In this experiment we would try to notice and map the here and now of the street – meaning – the always changing aspects of it.

-

Take a few minutes to stand and observe – what is moving around you? what is changing? can you notice situations that are appearing and disappearing?

-

Start voicing those changing elements (doesn’t have to be loud). Notice – while you are voicing them – are they already changing?

-

Noticing those ever-changing elements, start mapping them with your body –

Respond to shapes, movement, rhythm, respond to situations that you notice – this map doesn’t have to be anything – let it be what it is

2: Directions

Observe your surroundings — what directions are moving in space? What is the source of these movements? (People? Cars? Wind?) Notice when the movement is appearing and disappearing.

Close your eyes and then open them again. What has changed from the moment before? How is the street different?

What directions can move you?

Lean your weight into those directions.

Let your whole body be moved by them. In what ways can they take you?

Start noticing — can you feel, see, or sense more than one direction at the same time?

Begin following with different body parts — let your head follow one direction and your pelvis follow another. Let your legs follow one direction and your shoulders another… keep playing with different body parts.

Let yourself be overwhelmed.

Start showing the directions with your body parts, as if you are showing the way. Can you show more than one way at the same time? How clear can you be about the direction you are showing? Exaggerate.

Drop this, and start following the directions with the inside of your body.

What feels different? Play between the two.

Go back to moving freely and keep noticing the directions:

Follow in the way that you want to follow.

Start choosing which directions you follow.

Stick to the same direction as much as possible. How long can you follow it before it disappears?

Does it disappear, or does another direction take you?

Take some time to play with what you found interesting during the session — let yourself change your mind about it.

3: Sounds

Take a few moments to listen.

What do you hear? Cars? Voices? Rhythms? What sounds appear and disappear?

Start moving in the way you want to move, while continuing to notice the sounds around you.

Begin noticing words or sounds that evoke strong associations.

Respond to these sounds.

Respond through your associations to the sounds — don’t think about it. Move from one association to the next. What physical associations appear?

Can you answer these sounds with your body? In what way?

Start noticing — where are the sounds coming from? How far are they from you?

Can you move toward the sounds? With which body part?

Can you move toward more than one sound at the same time?

Experiment 2 – Responding to Different Physical Elements

(Tel Aviv)

In this experiment, I asked the dancer to respond to additional elements of the ever-changing city, such as sound, people, and again, directions.

General Reflection – Ariela

It was interesting to use things that I know from my everyday life in a different way.

What didn’t work for you:

Changing my perception was hard—I felt that I needed to change the way I see things. Usually, I don’t look at a moving car or a dog as an engine for movement. I had to stay very attentive and keep an open mind.

How it was to be public:

It was a fine line. It wasn’t a big audience, so I didn’t fully step into myself as a performer.

I felt that because I was constantly responding, it made me feel quite vulnerable.

If I had treated it immediately as a performance, I think I would have focused more on what I needed to do, and less on noticing what was happening

My reflection:

I was questioning the performativity of it — is it a performance? It seemed hard to meet the full body in the situation. I was questioning — how can the attentiveness not take away from the dance? How can I guide it in a way that will allow the dance to exist as a first, basic layer? Out of the motion, in the sound score — what I was asking seemed the most clear in the dancer’s body and intention. It felt that she was more comfortable responding to it

Ariela’s thoughts – 1 (free mapping)

Interesting. I had a question: Am I doing it right?

I asked myself what it really means to map, and I often found myself trying to recreate or repeat something I had seen.

Because I was imitating people, I tried not to be too obvious—so they wouldn’t change their behavior because of me.

I also tried to notice how I respond to things—does a loud noise make me jump? What about other kinds of sounds?

I tried to observe how I respond to non-human things too—changes in light, lights from cars—things that change but involve less movement.

Other non-human things—dogs, cars—what can I take from them that isn’t just direct imitation?

In my body, I felt some resistance to going into a big range of expression. Since I was looking at details, mapping them in a smaller way made sense to me.

Ariela’s thoughts – 2: Directions

It was interesting to try and understand when a direction is finished—and why.

Usually, I noticed that I stopped when I couldn’t see anymore, or when it stopped.

But then I realized that I could also wait for it to keep going.

It was hard—difficult—to try and follow more than one direction at the same time.

At some point, it became easier.

It felt more natural to move from the inside.

In the beginning, moving from the outside felt less right,

but then playing between the two offered interesting possibilities.

Suddenly, I had to remind myself to focus only on directions—

in contrast to the previous exercise.

At first, expanding into a larger range was really hard,

especially because of the public situation.

Closing and opening my eyes—knowing that everything was constantly changing—

brought me into the now of it.

Ariela’s thoughts – 3: Sound

The main difference I felt was in the spatial possibilities within my body—the musicality of what exists, and how the body interprets that.

Not necessarily in the same notion or spatial direction.

Because I already had the introduction with the directions, I felt that my body was, on one hand, still tuned to them, but on the other hand, it was something I could also let go of.

The mapping this time was less about the concrete space, and more about the abstract qualities within the sound.

I felt that I was dancing a little more—usually it’s easiest for me to dance with music, so this felt closest to what I know.

In the first exercise, it was easier to follow people; now it was easier to respond to sound—something I’m more used to as a dancer.

It was a bit more difficult with sounds that continued for a long time—how can I respond to something that feels static?

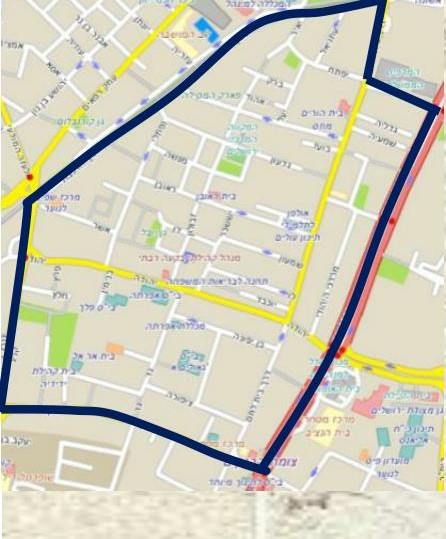

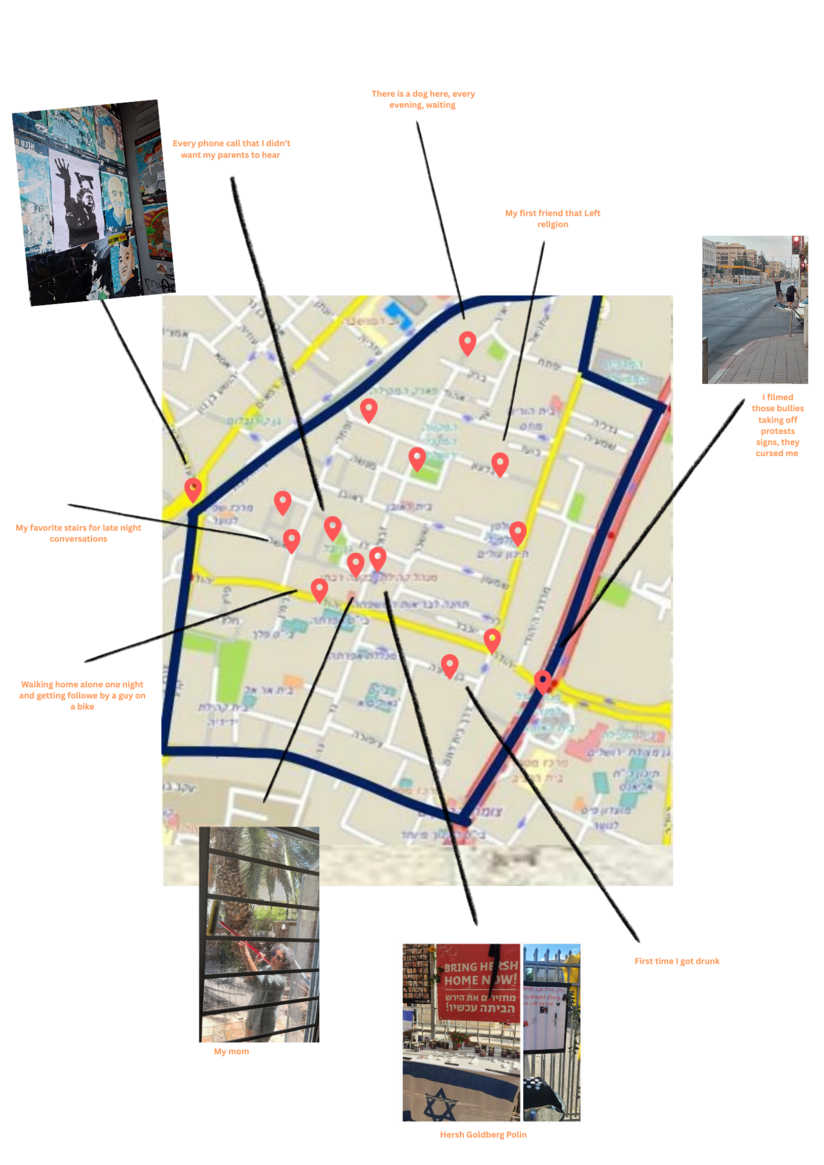

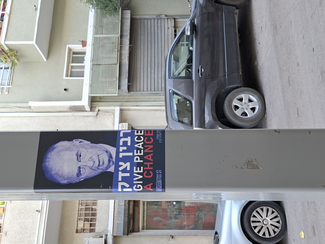

Observational Walk – The Invisible “Borders” Within the City

(Jerusalem)

During the experiments, I began wondering about the placement of my work—what exactly am I mapping? I started thinking about the invisible borders that exist within a city. In my city, Jerusalem, you can walk just a few streets from the busy market into the ultra-Orthodox neighborhood, where the city becomes a completely different situation. There is no real border—the border is shifting, fluid, and changing in the here and now.

I walked with a friend who lives in the neighborhood, and together we took photos capturing the here and now (of that moment) of these fluid borders.

Interview Ariela:

How was walking and taking photos in the beginning?

It was very helpful in getting in the state of noticing, later when I looked at things I looked at them as if I’m looking what to take photos of and it helped me to notice more.

Was it different in your attention then the last time when you stood in place and observed?

When you move you have a different way of noticing and paying attention- its less limited- if I want to go somewhere that attract my attention I can just go there. It allows to something else to happen because I can go to what interest me and what I want.

How was the mapping /walk/ performance?

First of all it was nice to have the option of walking as a base, if something in the space was interesting for me I could move towards it and if I didn’t have anything to respond to I could just keep walking – which is more active. Because a lot of what happened in the streets was people walking then something in this walk allowed me to respond to them in a more natural way.

Did you feel embarrassed? Was that stopping you?

In some way it was easier then last time – because something about last time putted me in a space where I was limited, and now even if I had an awkward interaction I could make choices about it and it was a momentary thing..

Did you feel that you are performing?

Sometimes I did but sometimes I felt that I’m hiding what I’m doing because of embarrassment..

Was there anything that could have helped you? If I would tell you it’s an official performance and even invite audience would that feel different for you?

Yes, also in the beginning in the instructions you said to allow it to be for yourself which I also took as allowing it to be internal, so I allowed it to also be for my self- knowing that not everything I’m doing is visible.

Could you imagine yourself working in a more performative way? What would be different?

I feel that I would have to move on a larger volume or scale- make my movement bigger. If I would make it clearly as a performance, I would have to make it very clear that this is a completely different situation then everyday walking.

But do you feel that you would know what to do and feel safe to do it?

I’m afraid that in this stage I would be too concerned about is it enough as a performance and less concerned with the actual task..

How was it for you physically? In the body?

You probably saw that I went with the same patterns. It was easy to to to the legs because of the walking pattern and to the hands.

I felt that I stayed very close to myself, maybe if I would allow myself to get further then I would feel more the performativity- because I would go out of myself a bit more.

How was me filming you?

I really tried not to let it influence me’ I made an active effort to ignore you but sometimes it did changed the way I acted.

Scores for Experiment 3

Dancer: Ariela Ben Dov

Tel Aviv- Yafo border 17.11.25

STAGE 1 : Walking, noticing, photographing

Introduction:

We will walk now from where we are ( Tel Aviv Yafo border) towards Yafo neighborhoods- I will monitor the general direction but the specific way in undefined

While walking – notice the moments of change in the situations of the streets. Ask yourself- what situations are clearly Tel Aviv? What are yafo? Notice your expectations and pre images.

take photos and collect sounds if you wish:

- of situations within the street that are making is what it is in the moment- isf the situation changes – the street would be different.

- Of elements that are defining one part of the city for you, elements that are belonging to one or the other side of this chainable fluid border within the city.

- Focus on not static elements- on situations that are changing. Focus on elements that are characteristic of one of the changing within the streets.

STAGE 2 : walking and mapping through movement

- We will now walk back loosely on the same pathway that we came from – I will monitor the way so you can walk freely.

- While walking notice the changing and defining elements happening in the streets. Respond to situations- what accrues in the here and now and is changing or defining the reality of the experience?

- Keep in mind the previous mapping that we did- you can respond to sound, directions, people movements.

- Focus on 3 options: 1. Map- explain or mark with your body 2. Respond to the situation 3. Shed light on the situation that exist.

- If you don’t have an impulse to respond- keep walking

- Take this as a small performance- and a silent walk. allow yourself to take it for yourself, focus on what interest you and allow yourself to drift from the task – I will not interfere unless you ask for input.

Experiment 3 – Embodied Mapping of the Invisible Borders

(Tel Aviv–Yafo)

In this experiment I decided to walk from Tel Aviv to Yafo. Yafo is mostly an Arab city, and although there is a border on the map, in reality it is not clear where one city ends and the other begins. Together with the dancer, I conducted an observational walk, noticing the changes in the city and taking photos in order to become more attentive to these shifts.

Later, I asked the dancer to walk back along the same route. This time she mapped the fluidity of the city with her body—responding to the changes through the physical tools that we used in earlier experiments (sounds, directions, and the presence of other people’s bodies).

Self-reflection:

I felt that the walking and taking photos in the beginning was a good way to explain my intentations and to sharpen the understanding of the specific elements that im looking for in the streets.

While walking, I noticed that the city took longer to change then I imagined before- the picture that I had in my head, the image of the city in the border between Tel Aviv and Yafo was different then in reality – I did not expect to notice the gentrification in the way that I did.

In a practical matter, I think the walk was too long – partly because it took much longer than I expected to reach a noticeable change in the city. I think in the future I should conduct a pre-tour/ walk and decide on a much smaller defined area.

Watching Ariela walk gave a different performativity to the situation – since the intrest is in the changeability it made sense to keep moving.

However, I didn’t find yet in her choices or movement a physical interest that could be developed in a clear way. Developed in the body.

I wonder- maybe the movement direction is wrong? Maybe the approach should be physical first? I’m not sure how to approach it in this way.

I think that the task is not yet physical and is not exploring a clear body interest and in that way it stays on the more “intellectual / thought/ observing” level and is not

I don’t yet find a physical reason for the dancer to move the way she does- I felt that she also don’t have this based on my instructions and it limited her ability to interpenetrate the task.

I would also want to reflect on the way I facilitate the situation. I need to find a way to create a situation that is defined enough and is giving the dancer the legitimation to fully explore from a place of body curiosity – I think that public space especially busy streets make us automatically a little afraid of exploring radically, of doing anything that would interrupte the “natural flow” of the street. I was thinking that maybe defining the situation more – is what needed to allow more freedom.

Rita’s Reflection

Noises or sensory inputs that usually annoy me were things I was able to surrender to, or even embrace.

It feels freeing to go with the impulses that come from my senses, and to go fully with them.

For example, imitating people is something I often feel tempted to do, and here I allowed myself to go with that impulse. Also, covering my ears in response to noise is not an action I would usually allow myself to do in my day-to-day walk, but now it became a physical action in response to the impulse.

I felt that this was about allowing myself to go deeper and in a more radical way into my senses.

Because of my concussion, I already notice a lot, but in this situation I felt that I noticed even more — for example, the direction of the water.

It is tiring to take everything in for a long time, but there is also something interesting about surrendering to all the senses. In a way, surrendering into the senses could direct my movement.

It is also interesting to be in the in-between: being both a pedestrian and a performer, and choosing and playing between those two states. In this performative walk, I felt that in a way I am already part of the performance that exists at any given moment in the street. I could “disappear” into pedestrian walking, or choose to respond in a more obvious, performative, physical way, and play between the two.

Experiment Stockholm December 2025

Dancer: Rita Warg

In July 2025 Rita experienced a concussion and is currently recovering from it. Since the concussion, she has a very high sensitivity in all senses, especially to sound, light, and touch.

As part of her recovery process, Rita walks the same pathway almost every day, with slight changes, in order to slowly get used to sensory exposure again.

Score

Walk the same walk that you walk every day.

This time, walk it as a performance.

Notice:

What elements in this walk make the city what it is in this moment?

What elements create the current situation at any given moment?

Notice and respond to the changing elements of the city — sound, people, weather, directions.

Notice your sensitivity.

What do you notice now that you did not notice before?

Notice and respond to the impulses that your sensitivity brings.

If you want to walk away from a sound or cover your eyes — do so.

Map the city that you sense in the moment in a performative way.

Dive deeper into what you sense and do not resist it.

Satisfy your needs and interests as a dancer and performer.

My Reflection

For me, this was the most interesting experiment so far. I defined the walk as a performance, and I felt that Rita, as a dancer experienced in improvisational performance, was able to work physically from her impulses and interests in the moment.

I felt that in this score and experiment—also because of Rita’s condition—there is a lot of weight on the dancer’s senses. This allowed for a more “full-body” approach. The movement was not necessarily “bigger” or more “physical,” but I felt that the improvisation was following an experience, rather than simply trying to fulfill a task.

I felt that there is space to go even deeper with the senses in relation to mapping the here and now, allowing the personal experience to be involved—experience as a physical, sensory experience.

Rita was able to emphasize what is already there. The city, as a situation, can be viewed as a performance, and Rita was playing between watching it and adding to it. This allowed for noticing situations that already exist in the city, for example, a person walking in a specific way or the wind blowing.

Walking was essential from this perspective. It allowed Rita to be dynamic and to change her relationship to the urban environment. Her personal experience also changed, which allowed her to respond in diverse ways and not be limited to one rule.

Experiment 2:

Malina: I was a bit unsure about the mapping because I didn’t want to just copy the forms that I saw.

Anna: I was also busy with that. Sometimes I shaped forms with my body, but somehow the outcome was less interesting for me than going more with the movement and directions.

Malina: I was also looking at forms and noticing what kind of sensation they gave me, and that was more interesting than the form itself.

Rut: What did you map? What caught your attention?

Malina: The texture of the snow was interesting. Also, there were a lot of lines and squares in the space. That also gave me a certain feeling. I think, generally, I was noticing a lot of visual patterns.

Anna: The sensations were definitely more inside myself than the mapping. The cold air made me breathe and expand. I was also moved a lot by smells. At some point, I was so overwhelmed by everything I sensed, but then I also had the freedom to react in the way I wanted to in the moment.

Rut: How was it different from the previous experiences?

Malina: I think the mapping connected me much more to these forms and patterns, but the sensations were not so different—I was in the same mode of being very open to the outside.

Rut: How was it as a performance?

Malina: I really didn’t care what other people thought—it felt safer in a way.

Anna: For me, it was nice because, within the performance, I had the ability to communicate more what was happening to me and what I was feeling at the moment, compared to just walking on the street. In a way, there was a nice freedom in responding to my reactions to the situation.

Rut: You both know this part of the city—was it new for you in any way? Did it matter that you knew the area?

Malina: I didn’t notice anything that really surprised me—I know the area well. But I also think that the experience wouldn’t be the same in an environment I didn’t know—there would either be something less overwhelming about it.

Anna: I would definitely say it made a difference for me. Just entering Berlin again after visiting my hometown is already a big change. This area, for me, is a lot about going somewhere, and in this way I’m always shutting down just to get where I need. So, in this way, it was very different to notice so much of the city like this.

Score

Anna Mozer + Malina Rotenstein (Berlin)

This is a performance.

This is a walk — if you don’t have anything to do, you can always walk.

This is a duet — you can always respond to and relate to each other.

Satisfy yourself as a dancer first! Go with what you want; go with the offers that are relevant or interesting for you.

Introduction

Take a short walk.

While walking, notice the details that make the situation what it is now.

Notice what is changing around you.

What do you hear?

How are people walking?

Is there wind? Snow?

What directions can you recognise in the space?

Close your eyes for a moment, then open them again — what has changed in the space compared to a moment before?

Close your ears for a moment, then open them again — what has changed in what you hear compared to a moment ago?

Role 1

Start focusing on what you sense — wind, cold, noise.

Can you sense the people around you?

Can you sense directions in the space?

React in the way you want to react.

If you are cold, cover yourself.

If you enjoy the snow, run in it.

React with and through your body.

Let your body respond to your senses — go radically into your senses and move from them.

Let what you sense guide your movement.

Role 2

Keep noticing what is happening around you.

What is always changing?

What is always moving?

Notice which elements around you are in motion — let them move you.

Map the changing elements with your body.

Respond to sound, directions, people walking, and the weather.

In what ways could they move you?

Try to create a bodily map of what is happening around you.

Reflection Experiment 1:

Malina: I really enjoyed it. For me, the snow was very dominant, and also my shoes. In the city, I was reacting to sounds—a lot of cars, some dogs barking. The consistency of the snow also influenced how I moved. I was also moved by the forms that I was noticing.

Rut: Did you feel that you were reacting more to things from the outside, or was the movement more distracting and you felt more focused on the inside of your body?

Malina: I think that, for me, it was more about the outside. Then I had moments where I went more inward, but I felt that I wanted to go from the outside.

Anna: I found it interesting to switch a lot between what is moving me—what I’m seeing and what I’m hearing. Sometimes the sounds led me to notice something I hadn’t seen before. I was also noticing people swinging their arms, something I hadn’t noticed before. Also, generally, the speed—the speed of people or cars.

Rut: What was mapping creating for you?

Anna: I think it was a lot about relating my body to what I’m seeing and hearing, and taking directions and forms into my movements.

Rut: How was doing it together? Were you noticing each other?

Malina: Yes. For me, I was definitely noticing. I was doing my own thing, but you were also part of it.

Anna: Just the situation of us moving already differentiates us from the city—we’re in our own situation. But I would say I was still more in my own world, while being able to relate. We also kept a distance in a way that brought us together.

A map says to you, "Read me carefully, follow me closely, doubt me not." It says, "I am the earth in the palm of your hand. Without me, you are alone and lost."

And indeed you are. Were all the maps in this world destroyed and vanished under the direction of some malevolent hand, each man would be blind again, each city be made a stranger to the next, each landmark become a meaningless signpost pointing to nothing.

Yet, looking at it, feeling it, running a finger along its lines, it is a cold thing, a map, humourless and dull, born of calipers and a draughtsman's board. That coastline there, that ragged scraw of scarlet ink, shows neither sand nor sea nor rock; it speaks of no mariner, blundering full sail in wakeless seas, to bequeath, on sheepskin or a slab of wood, a priceless scribble to posterity. This brown blot that marks a mountain has, for the casual eye, no other significance, though twenty men, or ten, or only one, may have squandered life to climb it. Here is a valley, there a swamp, and there a desert; and here is a river that some curious and courageous soul, like a pencil in the hand of God, first traced with bleeding feet.

—Beryl Markham, 1983 [1]

Article link: https://quod.lib.umich.edu/p/passages/4761530.0003.008/--deconstructing-the-map?rgn=main;view=fulltext

“The steps in making a map—selection, omission, simplification, classification, the creation of hierarchies, and ‘symbolization’—are all inherently rhetorical.”

In Deconstructing the Map, J. B. Harley argues that rhetoric is not an accidental feature of maps but a structural condition of all cartographic representation. Rejecting the distinction between scientific objectivity and persuasive distortion, Harley insists that “all maps are rhetorical texts,” because every map necessarily selects, omits, and organizes reality according to human intention. The processes of “selection, omission, simplification, classification, the creation of hierarchies, and ‘symbolization’” are not neutral technical steps but rhetorical acts that frame how the world can be seen and understood. Even so-called scientific maps rely on persuasion, not despite but through their claims to accuracy and neutrality. As Harley notes, in modern cartography “accuracy and austerity of design are now the new talismans of authority,” allowing power to operate invisibly beneath the appearance of objectivity. What appears as neutral representation is therefore a performance of truth, what Harley calls the 'sly ‘rhetoric of neutrality,’” through which maps assert authority while concealing the social values and power relations embedded within them.

score:

In response to the elements through which maps turn into prescriptive instruments that shape reality and produce power relations—not necessarily in a judgmental way, since these processes are unavoidable in human symbolic output—this score proposes a movement-based walking practice. It engages with the elements of mapping but offers an alternative to them

this score is (Not) mapping the city

1.selection and omission:

“The map-maker merely omits those features of the world that lie outside the purpose of the immediate discourse.”

walk the way you always walk

while walking notice - what do you see? What do you hear? What do you smell? notice what you notice , notice what you don't notice ( Israel Aloni)

notice what you always notice

notice in what way you can notice more than you usually notice

close your eyes and open it again - what changed around you?

2. simplification:

“In the map, nature is reduced to a graphic formula.”

start notice what do you sense physically from the city around you

what so you hear?

can you sense rhythms in the city? the rhythms of people walking? the rhythm of cars driving?

can you sense directions around you? the directions of the wind? of the cars? of the people/ does the street have a direction?

start moving while notice what you sense- in what way could you be moved by the city around you?

could you be moved by the directions around you? could you move with them?

In what way are you responding to what you hear? In what way are you responding the the texture under your feet? In what way are you responding to the cold air?

Dive deeper into what you sense and do not resist it.

allow yourself to be moved by what you sense around you

3. symbolisation and classification :

“Maps, like art, far from being ‘a transparent opening to the world,’ are but a particular human way of looking at the world.”

Start notice associations that you receive from what you notice

respond in the way you want to respond

if you want to close your ears because of uncomfortable noise - do so

if you want to imitate someone's walk do so if you want to observe closely, stop or walk way -

notice what are your impulses walking the city - go deeper into them in a physical way.

4. creation of hierarchy:

“The rule seems to be ‘the more powerful, the more prominent.’”

keep noticing directions, people, sounds, rhythm, texture

be selective in what you respond to

select by your impulse in the moment - nothing is more important from the other - it all depends on your experience

allow yourself to play in between your responses

allow yourself to change your mind

allow yourself to create an experience for your self