This exposition is published in the Proceedings of the 1st symposium Forum Artistic Research: listen for beginnings.

Polyphonizing as a Contemplative Practice1

Jakob Stillmark

Various developments within early electronic music as well as in American Experimentalism of the 1950s and 1960s have disclosed new concepts of explicitly contemplative listening practices. Composers like John Cage or Pauline Oliveros are well known for compositional approaches that embody techniques and experiences of either Buddhist or secular meditation practices.

This paper further investigates the relationship between listening, composition, and contemplative listening and proposes a new perspective on it by introducing the concept of polyphonizing. It offers a view of my recent artistic experimentation and how it was informed by the listening experience within a specific practice of sound meditation. Finally, using the example of my work Poly-Momente, I give insight into how I applied the concept of polyphonizing within my compositional process. On this basis, I argue that polyphonizing can become a useful approach in documenting contemplative experience artistically. Furthermore, it offers a new conceptual approach to polyphonic composition.

The initial pursuit of my artistic experimentation was driven by the specific phenomenon of a double perception that emerged while composing with musical quotations in repetition structures. Quotations – if recognized as such – are mainly perceived on a referential level. They refer to another, quoted piece of music, often with the motivation to convey a certain meaning or semantic link. But when used in repetition structures, they sometimes seem to lose their reference, as if the mere presence of their sonic materiality was more significant than their semiotic function. Similar to the phenomenon of semantic satiation (Balota and Black 1997), the semantic level of sounds becomes less relevant with each iteration and variation. The attention of listening begins to focus on other qualities of sound. It becomes freer in a certain respect but is simultaneously called upon to take on an active role.

- This article summarizes a lecture given at the Forum Artistic Research in Klagenfurt and at the International Society for Contemplative Research conference (June 2024). It also includes translated excerpts from my dissertation, Vermehrstimmigen als kontemplative Praxis. Wiederholung, Fragmentierung und Mehrstimmigkeit im Komponieren mit musikalischen Entlehnungen (Stillmark, n.d.) which explores these topics in greater depth.

This phenomenon becomes evident it the example of a compositional experiment, in which I took a famous Austrian melody,2 full of controversial layers of signification and expression (Fig. 1). I then cut out short fragments from it and recomposed them together with other samples of E♭ major sounds, the tonal center of the melody (Fig. 2). While in the first example the many layers of significance intrinsic to the melody are quite intrusive, the second example broadens the perspective on the cut-out piano sounds. The melody and its meaning can still partly be recognized or suspected, but it is contrasted by multiple new perspectives that the recomposition of the sound material discloses.

As much as these moments fascinated me, I did not know how to exactly deal with them compositionally. How did these moments arise? Could they be consciously produced? If so, how? Did they emerge on the basis of specific structures of repetition, fragmentation and variation, through the constellation with other quotations, or both?

In search of answers to these questions, I began to work on subsequent experiments in which I focused on multi-layered repetition structures that draw only from a single source quotation. In one of these experiments, I took sound material of So nah dran – an earlier Violin Solo composition of mine – which involves Johann Sebastian Bach’s d-Minor Violin Partita (BWV 1004). In the first stage I composed a 4-channel sound installation in which three different layers of repetition overlapped. One of these consisted of fast cuts with samples of max. 3 seconds3 (Fig. 3), another consisted of multiple simultaneous layers of larger excerpts of the Gigue, played with a practice mute (Fig. 4). The last worked with enormous slowdowns from the Chaconne (Fig. 5). In addition, I composed a part for Solo Violin that would accompany the sound installation performatively, which also uses various short motivic fragments of So nah dran.

In this way, a multi-layered structure of repetition emerges. Four processes of circling time – each differing in meter and tempo – overlap. Like the principle of self-similarity, the internal structure of each of these layers is also organized as a multi-layered interweaving of repetitive patterns. These patterns follow non-linear and open-ended processes, which give rise to the impression of aimless circling.4 The outcome of this experiment became the composition So nah dran II (Fig. 6).

What is particular about this compositional method is that it unfolds purely on the horizontal axis. Only the progression of the individual layers is shaped, which are then superimposed. In this sense, one could speak of a collage of different temporal processes.

Since the sonic material in all temporal layers is very homogeneous – due to the implicit tonality resulting from the Bach borrowings – connections between the layers repeatedly arise. Like a kaleidoscope, they present themselves in ever-changing constellations that could only be partially anticipated before the compositional process.

On a large-scale formal level, this results in a complex network of musical memory in which the identities of the repeated sounds are continuously re-actualized in the now. Such a radically horizontal approach to composition may work well for an installation format such as So nah dran II. However, during the rehearsal process, during the performance, and after repeatedly listening to the recording, I found that some constellations appeared much more fitting than others.

The collage-like character also led me to perceive an increasing indifference between the individual layers. While some particularly beautiful constellations did emerge, they were always shaped by the almost mechanical unfolding of the programmed temporal processes. These moments created instances of resonance, yet they were not structural embeddings but rather fortunate coincidences.

This raised the question of whether a similarly circling network of musical memory could be created in which a compositional approach to the vertical temporal structure is also possible – and to what extent the circling layers could be brought more deliberately into resonance with one another.

Although similar questions had emerged in other compositional experiments, it was a coincidental experience while preparing the audio tape for my piece Stop and Go (for string quintet and ghettoblaster) that offered a new perspective on a possible solution.

The core concept of the audio tape composition was to begin with a digital edit of a recording of Franz Schubert’s string quintet, transfer it to analog tape, then make a digital recording of the tape playback, which would subsequently be transferred back onto tape. I repeated this procedure about seven times. In some of these recording loops, I let the window of my apartment open, so that the multitude of ambient sounds present outside in the city center suddenly became part of the recording (Fig. 7–9). After re-recording this digital version back onto cassette, the spatial positioning of the tape recorder became audibly reflected in the sounds it played back. Listening to these recordings again with the window open – so that similar external sounds would once more enter the room – confronted me with a highly paradoxical perception of acoustic space.

On the one hand, my attention was centrally directed toward the ghettoblaster, trying to block out ambient noises that might disturb the listening experience. On the other hand, I recognized these same sounds within the playback – now entangled with the faded Schubert recording. In this context, I no longer blocked them out but instead integrated them in my perception, along with the Schubert material, as part of a complex and heterogeneous musical texture. The environmental sounds formed a multilayered structure in which each sonic identity emerged and disappeared in its own temporal progression: birdsong, traffic noise, construction work, etc. Each layer constituted its own pattern of repetition, continually forming new constellations with the other layers.

Since this texture was essentially a “sample” of my actual sonic environment at the moment of listening, I began to reflect on my own spatial situatedness and to perceive that very environment as a musical structure. Whereas my focus had previously been unidirectional, directed toward the cassette player as the sole source of sound, I became increasingly aware of my surrounding acoustic space during the processes of recording and re-recording.

The reflexive and transformative nature of this listening experience reminded me of a series of experiments I had conducted independently of my artistic practice in the context of my work as a Qìgōng instructor.5 In that context, I practiced a form of listening meditation, in which one focuses on one sound after another. One reflects on a sound in terms of its emotional impact and perceives it in its purely sonic qualities. The meditators are then asked to offer the “gift of an inner smile” to the sound before turning their attention to the next sound.

The aim is to direct awareness toward the richness of surrounding sounds and, in doing so, to practice a decentering of perception from emotional attachment. The “gift of an inner smile” serves as a metaphor for what cognitive science refers to as metacognitive insight or metacognitive awareness (Dahl et al. 2015). As Asaf Federman puts it, this is “the experience of thoughts as impersonal mental events that come and go” (Federman 2021, 466).

This kind of listening meditation can be categorized as a form of attentional meditation, a category that Dahl, Lutz and Davidson use to describe practices that enhance self-regulation of attentional processes and establish meta-awareness (Dahl et al. 2015). As neuropsychological studies have shown, attentional meditation reduces brain activity related to mind wandering and rumination, while areas related to attention control showed higher activity. Federman summarizes it as follows: “Phenomenologically, they were better at suppressing thinking about what they felt, and better at sustaining attention on the feeling itself” (Federman 2021, 465).

Translating this into the act of listening to music means thinking less about what is being heard and its emotional impact and instead becoming more attentive to its sonic shape – or, put differently, practicing a more differentiated and reflective mode of listening.

In the aforementioned experiments, I modified the listening meditation by playing music by Bach through simple phone speakers after about five minutes of silent listening. Over the course of five minutes, I gradually increased and then decreased the volume. In this way, both I and the other participants were invited to reflect on our emotional reactions to the music and to focus on its purely sonic qualities. Rather than serving a calming, meditative function – as many types of meditation music aim to do – the music became the object of intensive and attentive listening.

After practicing this kind of modified sound meditation several times, I began to notice a shift in how I perceived the music during meditation. I still noticed the emotions, associations, and expectations I linked to the music (which I knew very well), but now I experienced them as cognitive acts running parallel to the sound itself: acts that were separate from the music’s sonic manifestation. I increasingly began to perceive the latter as part of a heterogeneous texture composed of simultaneously present ambient sounds.

I observed how my attention oscillated. On one hand, I no longer perceived the music primarily as music, but simply as another sound – something that, as Federman describes in the context of metacognitive awareness, appears as a mental event and then fades. On the other hand, just as when listening to the cassette, I began to perceive my entire environment as a musical structure. Thus, in both the listening to the cassette and the sound meditation with music, a simultaneity emerged between metacognitive awareness and aesthetic experience.

The interrelation between meditative and aesthetic experience is, especially in music, not a new idea. Works such as 4’33” by John Cage or Sonic Meditations by Pauline Oliveros have become exemplary for a fusion of these two modes of perception.6 Yet the comparison between cassette and sound meditation reveals a specific dimension of this interrelation. In both cases, metacognitive awareness and an expansion of aesthetic experience are facilitated through a polyphonic structure.

Clearly, the term polyphony in this context is not to be understood in the sense of traditional music theory. It must be distinguished from the specific contrapuntal approaches that developed in modal and tonal music since the 13th century. Nor can it be adequately explained through more recent definitions that reduce it to collage techniques or complexism.7 Rather, a new understanding of the term begins to emerge here that returns to the etymological basis of polyphony as many-voicedness: a structure of resonance between various simultaneously present sonic figures and their respective temporal trajectories. In both composition and meditation, polyphonizing then becomes the result of an aesthetic-contemplative practice in which sonic perception is multiplied.

In the context of meditation, polyphonizing refers to the practice of contemplatively experiencing the play of overlapping temporalities among simultaneously present sonic figures. In composition, polyphonizing refers to the practice of constellating different sonic figures within a shared temporal frame, thereby modeling the polyphonic structure of contemplative experience through compositional means. In both meditation and composition, polyphonizing unfolds in two consecutive phases: first, through the differentiation of sounds into multiple layers and figures; and second, through bringing these layers and figures into resonance with one another.

Building on this discovery, the following section will aim to concretize how I applied this concept of polyphonizing in the compositional process of my work Poly-Momente.

- However, both composers have been repeatedly subjected to critical commentary within the framework of post-colonial reflections. The focus here is particularly on a certain unscrupulous syncretism in which an implicit Western ethnocentrism is often concealed. This may happen through the mystification of East Asian philosophies, whereby centuries-old colonialist stereotypes about the “exotic Orient” are reproduced (Lehnert 2008). For example, Pauline Oliveros’s Sonic Meditations and Deep Listening writings often mix meditation practices from various religious traditions without clearly acknowledging their cultural origins. Some of these, especially from Indigenous cultures, are presented as her own ideas, raising concerns of cultural appropriation (Browner 2000). Ian Pepper and Christian Utz extensively discussed this topic regarding the music of John Cage (Pepper 1999; Utz 2002, 99f). These criticisms must remind us that in engaging with transcultural perspectives, a nuanced, reflective, and respectful acknowledgment of the spiritual dimensions of such experiences is essential, particularly as they will always remain partly opaque and unfamiliar.

- A well-known example for this narrowing of the discourse is the publication Polyphony and Complexity by Claus Steffen Mahnkopf (2002).

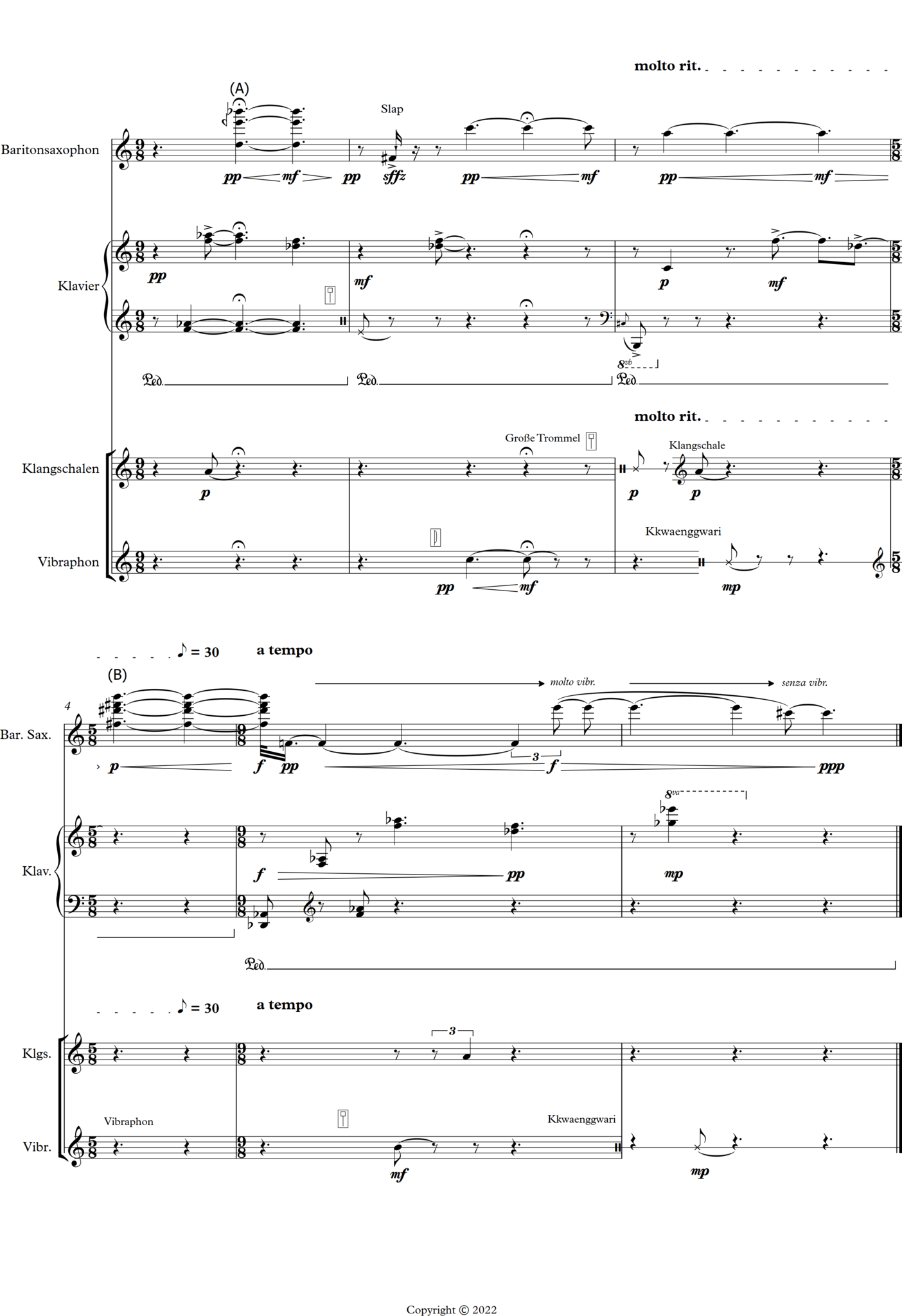

Poly-Momente is a 30-minute-long composition for baritone-saxophone, piano, percussion and electronics.8 My aim was to create a formal structure that would mirror the aforementioned experience of polyphonizing: a constellation of layered, repetitive processes shaped by variation and fragmentation, each unfolding along its own temporal trajectory and orbiting distinct sonic identities.

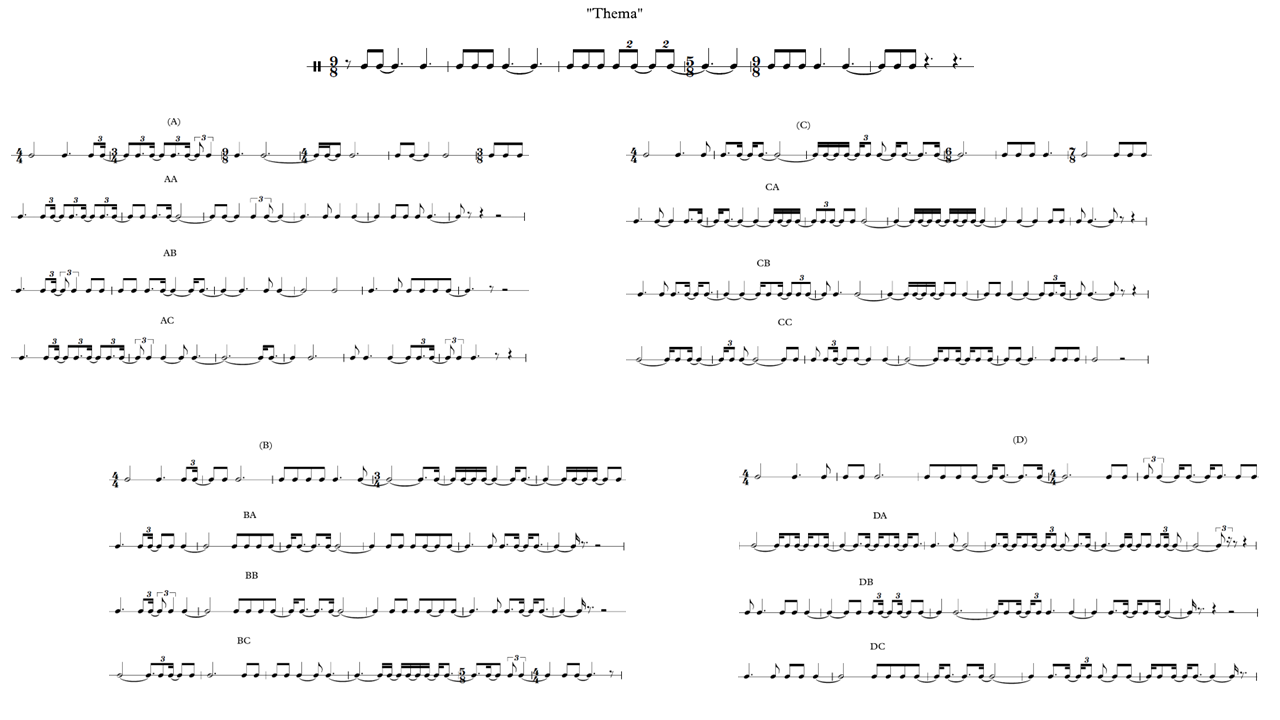

To begin with the first phase, the differentiation of sounds into multiple layers and figures, I prepared the “theme”: an edited compilation of a few bars from Claude Debussy’s Clair de Lune (Fig. 10). As a first step, I developed a procedure which would allow me to define different sound identities that I could then use to create multiple layers of repetition, fragmentation and variation. Therefore, I extracted its resulting rhythm, from which I created a series of variations (Fig. 11). With the help of a randomizing algorithm, I created several generations of variations. The algorithm was based on the following rules: (1) The first note becomes the last note. (2) A randomly selected tone is lengthened by a factor of 3/2. (3) Another randomly selected tone is shortened by a factor of 2/3. (4) Two randomly selected notes are swapped in position. In a first iteration, I generated four different variations of the “theme.” From each of these, I then created three additional variations in a second iteration. This resulted in a repertoire of a total of 17 distinct rhythms which, on the one hand, retained strong similarities, and on the other, developed in very different directions.

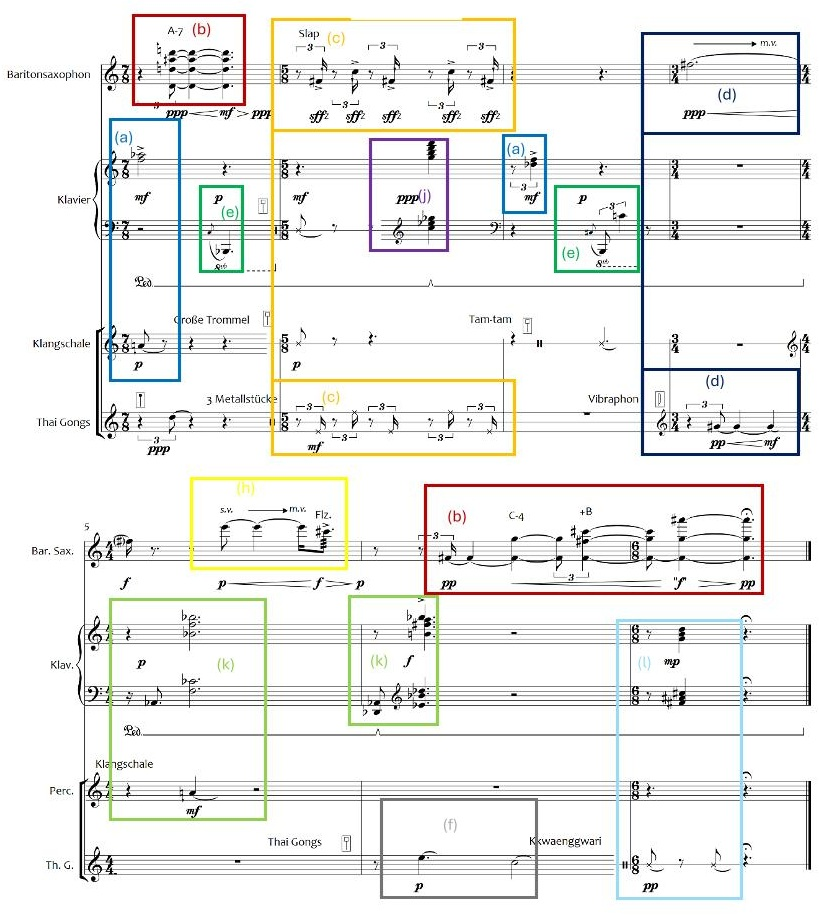

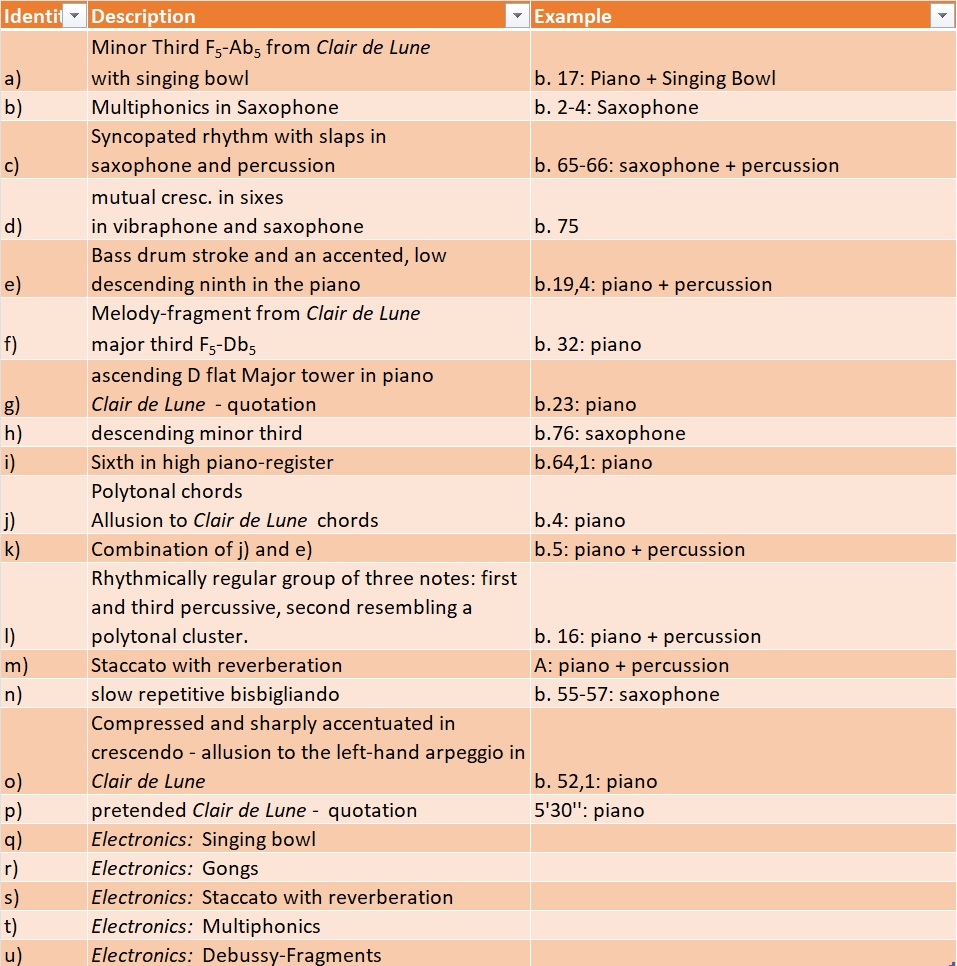

I then composed the new rhythms according to the following system: in those parts of the rhythm that remained unchanged, I also preserved the original sonic character, varying it only slightly. In contrast, for the newly developed parts, I created entirely new sonic characters. Once I had composed each of the 17 rhythmic variations into such micro-compositions, I began to break them down into their individual components. In this way, a large collection of 16 distinct sonic identities developed, each already comprising a set of variations. For each of these sonic layers, I then composed additional variations (Fig. 12).

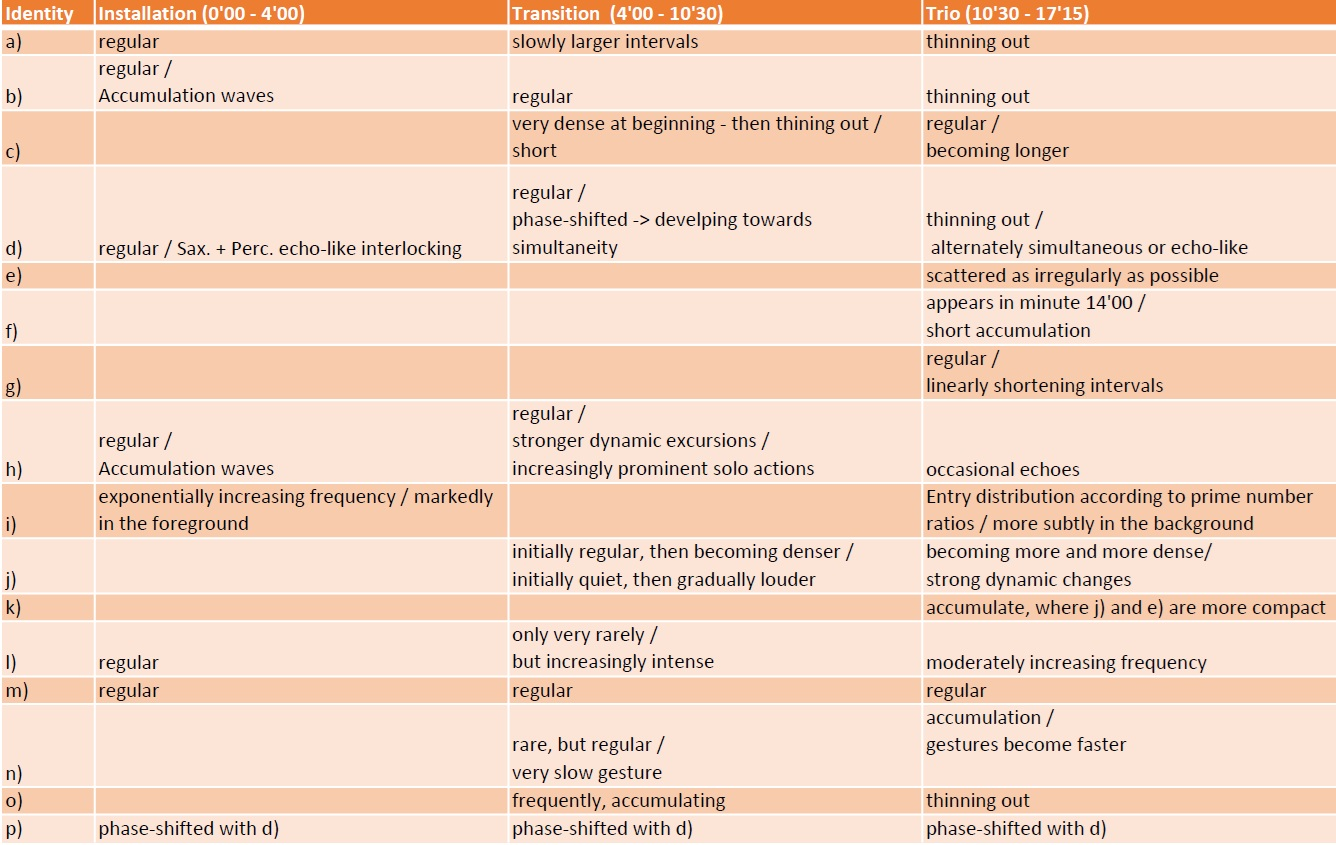

In addition, I designed five additional layers for the electronic playback, each derived from one of the sonic identities of the trio. An overview of all 21 sonic identities is provided in Fig. 13. In order to create a network of remembering and forgetting, I determined the appearance and disappearance of each identity in a large-scale formal plan spanning the entire duration of the piece. Within this plan, each sonic identity follows its own temporal trajectory of densification and thinning (Fig. 14). Based on this formal framework, I assembled the sketched variations and created the final score.

The piece is divided into three phases: an installation phase, a transition phase, and a purely instrumental phase. The installation phase has a duration of exactly four minutes and can be repeated any number of times. Meanwhile, the audience enters the hall, moves freely around the performance space, and is then led to their seats. The subsequent transition phase is no longer installative. The audience should already be seated, while the musicians are still spatially separated. The cues are still structured according to timecodes, however some figures are now synchronized between the musicians and notated in meter. During the transition phase, the saxophonist gradually comes onto the stage. The final part begins after the playback electronics have ended. It is a purely instrumental and completely metrically organized section. The goal of this hybrid-installative concept was to make the complex temporal network structure also spatially experienceable.

In this way, a complex and intricately nested network of remembering and forgetting emerges. The many different layers all come to the foreground of the musical events in their respective cyclical progressions and retreat into the background or disappear. The configurative form that results from the overlapping repetitive processes is far more flexible and differentiated than in So nah dran II. The sheer mass of 21 sound identities in total, which constantly establish new spatial and temporal relationships with one another, makes it nearly impossible to focus on just one level of events. Thus, while the momentary sound situations are clearly surveyable and transparently audible, no processual development can be discerned. Instead of developing, the form seems to be circular. The individual sound identities do not form developmental processes, either. When they sound, one recognizes them; when they fade away, they also disappear from memory. An example is sound identity p), a figure that seems to be a quotation from Clair de Lune but is not. The figure appears for the first time at the beginning of the transition phase, then densifies very strongly, only to thin out again afterwards. In the “trio” phase it appears only three more times. Put simply: the figure appears, pushes itself into the foreground, as if it had always been there, only to be quickly forgotten again, since other sound identities have meanwhile already established themselves in the proceedings.

Figure 15: Video of the world premiere of Poly-Momente. 17th aDevantgarde-Festival 2023, Concert SPEHRE:X. Recording of June 24 2023, schwere reiter münchen. Trio Abstrakt: Salim(a) Javaid, baritone saxophone; Shiau-Shiuan Hung, perussion; Marlies Debacker, piano. Audio-recording: BR-Klassik, Andreas Fischer. Filmcrew: Friedemann von Rechenberg (production, cutting, audio), Simon Herrmann (camera), Felix Länge (camera). Source: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KmEyGB3CWlc (accessed 03 Nov 2025).

This temporal structure of sonic identities appearing and disappearing is mimicking in a way what Federman described as the temporal structure of meta awareness during meditation: the coming and going of cognitive acts. Following on that, polyphonic structures could be seen in a certain sense as depictions of the poly-temporal experience of presence during contemplative practice. Yet the term of depiction suggests a static momentary conception: as if one could capture and preserve a particularly unique constellation of temporal layers through a snapshot. However, within the practice of polyphonizing the depiction of poly-temporal experience of presence is itself a temporally unfolding process in which that highly dynamic configuration is reflected as such.9

As the example of Poly-Momente showed, this process is characterized by a permanent alternation between experimental compositional determinations, immediate sonic experiences (even if this only takes place in the imagination at one’s desk at home), and their reflexive realizations which are decisive for further compositional decisions. The composition that gradually materializes through this process and becomes fixed in writing is to be understood less as the “result” of this process than as its traces, left behind on the score paper or – less romantically – in the notation software. These traces are documents of the process that can become intersubjectively experienceable. What is documented is not the immediate sonic experience itself, but rather the kaleidoscopic field of compositional decisions from which its reflexive representation emerges indirectly and as a negative.

The practice of polyphonizing thus has the potential to become an artistic method for researching contemplative experience. Similar to, for example, the interview methods of micro-phenomenology (Petitmengin, Remillieux, et al. 2019; Petitmengin, Beek, et al. 2019), techniques are employed that give expression to detailed descriptions of subjective experience. While these are mediated through language in micro-phenomenology, in composition this occurs through the mediation of various musical aspects that unfold in the polyphonically expanded kaleidoscopic field.

Furthermore, it bears a new approach to thinking about the concept of polyphonic composition, starting rather at the basic phenomenology of listening than at the discussion about merely diastematic contexts which must become increasingly complex in order to still be of interest.10 In a world of continuously diversifying contexts of reality, in which more and more disparate worlds sound simultaneously, polyphonizing may offer a technique of creating a tactility for spaces of resonance instead of slowly giving away to the gradual increase in overstimulation and indifference.

- Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf describes complexism as the most extreme and bizarre form of polyphony in his Theory of Polyphony (2023). Nevertheless, his phenomenological accounts on polyphony, in which he introduces the terms of “diagonal listening” and “apperceptive overload”, bear interesting resonances to the practice of polyphonizing (see Stillmark, n.d., pp. 218f).

References

- Bach, Johann Sebastian. Violin Partita No.2 in D minor, BWV 1004.

- Balota, David A., and Sheila Black. 1997. “Semantic Satiation in Healthy Young and Older Adults.” Memory & Cognition 25 (2): 190–202. doi: 10.3758/BF03201112.

- Browner, Tara. 2000. “‘They Could Have an Indian Soul’: Crow Two and the Processes of Cultural Appropriation.” The Journal of Musicological Research (Philadelphia) 19 (3): 243–63.

- Dahl, Cortland J, Antoine Lutz, and Richard J Davidson. 2015. “Reconstructing and Deconstructing the Self: Cognitive Mechanisms in Meditation Practice.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences (England) 19 (9): 515–23.

- Debussy, Claude. Suite bergamasque for piano, Clair de Lune.

- Federman, Asaf. 2021. “Meditation and the Cognitive Sciences.” In Routledge Handbook of Yoga and Meditation Studies. Routledge.

- Lehnert, Martin. 2008. “Inspirationen aus dem Osten? Aneignungen zwischen Identifikation und Universalitätsanspruch.” In Sinnbildungen. Spirituelle Dimensionen in der Musik heute, edited by Jörn Peter Hiekel, vol. 48. Veröffentlichungen des Instituts für Neue Musik und Musikerziehung Darmstadt. Mainz.

- Mahnkopf, Claus-Steffen. 2002. Polyphony and Complexity. 1. ed. New Music and Aesthetics in the 21st Century 1. Wolke.

- Pepper, Ian. 1999. “John Cage und der Jargon des Nichts.” In Mythos Cage, edited by Claus-Steffen Mahnkopf. Hofheim.

- Petitmengin, Claire, Martijn van Beek, Michel Bitbol, Jean-Michel Nissou, and Andreas Roepstorff. 2019. “Studying the Experience of Meditation through Micro-Phenomenology.” Current Opinion in Psychology 28: 54–59. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.10.009.

- Petitmengin, Claire, Anne Remillieux, and Camila Valenzuela-Moguillansky. 2019. “Discovering the Structures of Lived Experience.” Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 18 (4): 691–730. doi: 10.1007/s11097-018-9597-4.

- Schubert, Franz. String Quintet C-Major, D 956, op. post. 163, Adagio.

- Schumann, Clara. Impromptu in G Major, Op. 9, “Souvenir de Vienne”, performed by Susanne Grützmann, Clara Schumann. The Complete Work for Piano Solo, Profil Hänssler, 2007, CD.

- Stillmark, Jakob. n.d. Vermehrstimmigen als kontemplative Praxis. Wiederholung, Fragmentierung und Mehrstimmigkeit im Komponieren mit musikalischen Entlehnungen. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- Utz, Christian. 2002. Neue Musik und Interkulturalität: Von John Cage bis Tan Dun. Beihefte zum Archiv für Musikwissenschaft 51. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag.