This exposition is published in the Proceedings of the 1st symposium Forum Artistic Research: listen for beginnings.

The lecture’s context

In my lecture at the Forum Artistic Research on June 27th, 2024, I explored the development of relations in artistic collaborations that combine individual and collective practices. My reflections were guided by the question of how the activity of listening engenders and facilitates relations between the participants of collaborative creative situations. This quest stems from my artistic doctoral project Refiguring Composition that I pursue since 2021 at the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna (Flick n.d., in preparation). Rooted in the composer-saxophonist-improviser’s fascination with a musical composition’s seemingly endless transformative potential, I researched what activities a musical composition is part of, how it is formed and transformed, and how the participants of creative situations are related through their interaction. What became the methodological core of my research is an artistic working method of individual and collaborative compositional situations that permitted experimental setups of iteratively combined creative activities.

Musa Horti and The Enchanted Forest

The basis for the following reflections is the research’s penultimate collaborative experiment that ran between June 2023 and February 2024 together with the choir Musa Horti from Leuven, Belgium, conducted by Peter Dejans. The goal was to “write a new piece for Musa Horti with a focus on the contact and the transitions between written and improvised parts,” a piece that would originate in “improvisation exercises and experiments with the choir” (Flick 2023c, 1), which we would carry out in an initial improvisation workshop. When reflecting on the workshop’s activities and the score of The Enchanted Forest created subsequently with the workshop’s happenings as a starting point, I became particularly interested in the very beginnings of the relational processes between the workshop and my score writing. I wondered which role the activity of listening played here.

The collaboration’s starting point

Musa Horti is a renowned and extraordinarily accomplished lay choir, with a focus on contemporary (Flemish) Western classical repertoire. As in most choirs performing such repertoire, Musa Horti’s music-making is usually organized through the interaction with a score and a conductor. In contrast, improvising would imply interacting without the situation pre-structured by a score or a conductor. This would lead to other contact processes and thus other kinds of relations among the singers as well as between the singers and the musical Geschehen:1 the evolving sound that is created together, and that the musicians would need to become aware of.

Awareness of the own body’s interaction with the surroundings became the starting point for the workshop. This could be understood as tacit knowledge, following Michael Polanyi who developed the concept through Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s philosophy of the body: “Our body is the ultimate instrument of all our external knowledge, whether intellectual or practical. In all our waking moments, we are relying on our awareness of contacts of our body with things outside for attending to these things” (Polanyi 2009, 15f). Likewise, Alva Noë’s enactive approach to perception2 shows how, through this interaction with the surroundings, we experience ourselves, and how our consciousness is formed: “By changing the shape of our activity, we can change our own shape, body, and mind. Language, tools, and collective practices make us what we are” (Noë 2010, 67).

- Applying the term Geschehen from my native language German—a term that seems to lack an English equivalent—the neologism musical Geschehen developed as a reflective tool within my doctoral research project to describe and to emphasize the dimension of continuity of the evolving sound made by participants interacting in a creative situation. Geschehen denotes something that continues, lingers, or is held up and ongoing over time. Similar to the term ‘event,’ which, despite differences in meaning, is often used as its English translation, it denominates something that happens in a certain instant of time, while simultaneously paying attention to the complex totality of related and entangled sound movements. In addition to sound that can be perceived by the human body-mind-unity’s senses, the musical Geschehen can even refer to a vision or anticipation of sound.

- “Perception is not something that happens to us, or in us. It is something that we do” (Noë 2004, 1).

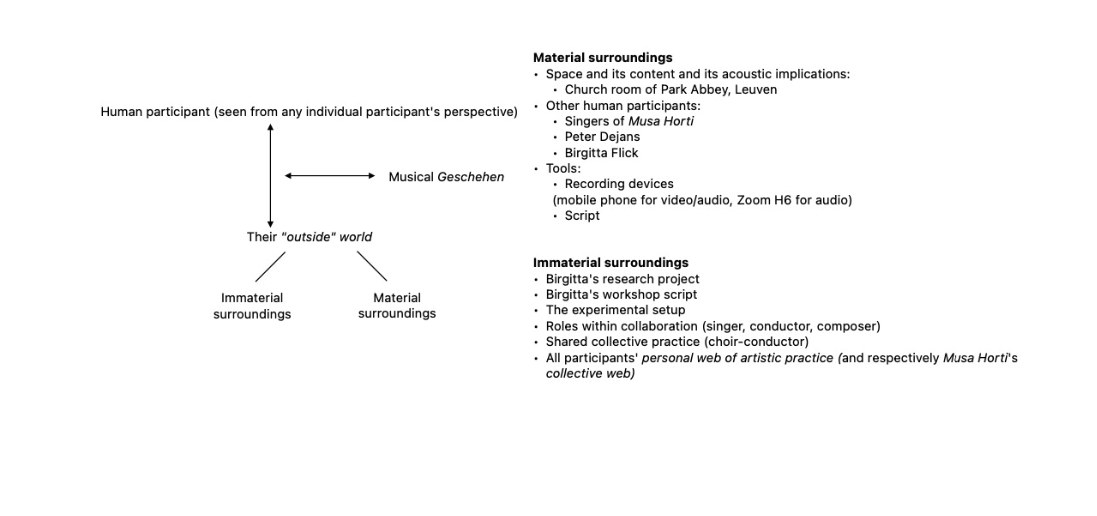

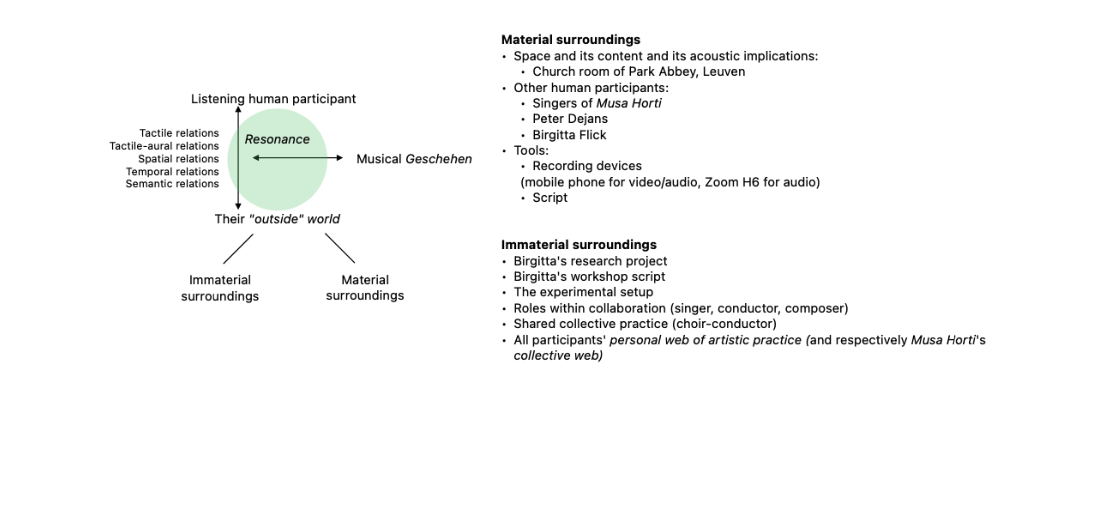

To get an overview of the creative situation of the workshop, I drafted a first chart of its participants (Fig. 1), inspired by Tasos Zembylas’ and Martin Niederauer’s topography of composition processes (Zembylas and Niederauer 2019, 14).3 Seen from an individual’s perspective, a human participant4 interacts with the “outside” world,5 physically consisting of other human participants and the material surroundings (here, in particular, the church room of Leuven’s Park Abbey with its acoustics). There are also immaterial surroundings: everything that directly or indirectly influences the participants of the situation. This includes the framework of my workshop concept, my research, the roles we have in and outside of the workshop, and each participant’s “web of artistic practice” (Coessens 2014, 69–81).6

The workshop

The workshop began with a series of exercises7 to train awareness in relation to the surroundings and to the various musical Geschehen created together. The first exercise:

Perceive yourself breathing. Listen to your breathing; the inhalation or inspiration, the exhalation, the pause or rest before the next inhalation. Perceive if you exhale through the nose or the mouth. If you have a preference, follow this for a while, but start then testing how it feels to change to the other option. How does your breathing sound? Do all parts of the breathing cycle make sound? Do the sounds differ? (Flick 2023c, 2)

Perceiving

The first instruction, “Perceive yourself breathing,” invites to become aware of a contact process: through breathing, our body interacts with the surroundings in constant movement and thereby becomes tactilely entangled with it. Through perceiving our breathing, we gain the most basic knowledge of how our own corporeality is related to the surroundings.

Listening-obeying-transforming

The next instruction, “Listen to your breathing,” specifies this general perception. Jean-Luc Nancy evokes the French formulation of “tendre l'oreille” (“stretching the ear”), describing how “[e]very sensory register thus bears with it both its simple nature and its tense, attentive, or anxious state.” Listening functions as the intensification of the activity of hearing (Nancy 2002, 18; Nancy 2007, 5). Importantly, the activity of listening—as any sensual and sense-making activity—is directional and always encompasses the unity of body and mind. This procedure of directing could also be described as obeying, or following; a dimension that is etymologically innate in the term of listening.8

Another dimension of interest is the transformation that listening brings, and how different concepts of resonance are connected to it. When I listen to sound, I listen for a resonance, and I actually interact with something that is already an interaction apriori. In other words, I can never listen exclusively to myself or exclusively to something else. I listen to myself involved in contact, obeying-following, becoming transformed. And neither is this transformation purely physical: if and how I listen depend on my whole lived experience. Again citing Nancy:

To be listening is thus to enter into tension and to be on the lookout for a relation to self: not, it should be emphasized, a relationship to “me” (the supposedly given subject), or to the “self” of the other (the speaker, the musician, also supposedly given, with his [sic!] subjectivity), but to the relationship in self, so to speak, as it forms a “self" or a “to itself” in general. (Nancy 2007, 12)

Hartmut Rosa highlights this aspect of transformation in his sociological concept of resonance: resonance occurs when I become transformed through my own active answer to something that has “called” me. This may be a sound that I perceive and which thereby transforms as well. However, Rosa emphasizes the characteristic of “uncontrollability”: I can never force resonant relations (e.g. to human beings, things or musical Geschehen), nor can I fully prevent them. Neither can it be predetermined in which way things become transformed (Rosa 2020, 32–39).9

Nevertheless, I may try to establish preconditions for resonant relations through listening and therefore through obeying to what “calls” me.

Analyzing

The subsequent instruction yields another more general perceptive activity: “Perceive if you exhale through the nose or the mouth.” The dimension of analysis is added, requiring prior knowledge of what will be analyzed through perceiving and listening.

Ausloten: sounding the space

After a while, the questions and instructions began to widen their scope: from attending to changes through movement within the body to moving the body through the space and making sound. While moving, the singers were invited to pause from time to time while continuing to listen, as well as to especially seek contact with something or someone through humming, thus sounding (ausloten in German) the space and their own position within their "outside" world, tactilely, tactilely-aurally.10

Improvised unison

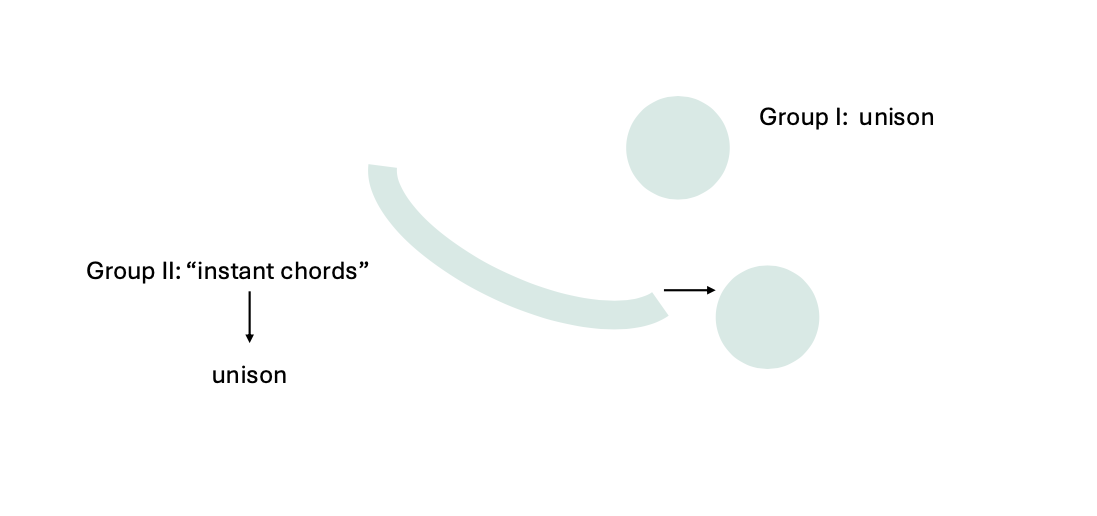

Following the introduction, we continued trying out different ways of interacting and relating through sound. One exercise was to collectively improvise a unison melody: first, one singer was leading the group and the others were following, then the situation was transformed by the choir so that anybody could introduce a new pitch. The singers developed a sounding togetherness, becoming a tentatively moving unison Klangkörper through the ongoing activity of listening-obeying-following, attuning in reference to sound color and pitch. This listening-attuning also afforded new spatial explorations: in the abbey with its long reverberation, spatial closeness was required to be able to hear well, leading to performing this exercise in smaller groups standing in a close circle and facing toward its centre. We then explored further spatial constellations, combining the unison with other interaction modes. Fig. 2 shows an example from one unison circle and one half-circle of conducted “instant chords,”11 transitioning into another unison circle. The audio example of Fig. 3 provides a recorded excerpt of this transition.

- Their research of composition processes was guided by the question of “what constitutes artistic agency” (Zembylas and Niederauer 2019, 1), focusing on tacit knowing in Western contemporary art music composition. They used the term ‘topography’ as a metaphor “to set out the web of practices, material constellations and professional relations within which creative processes of composition take place” (ibid., 13). Since my research interest is different and the activity of creating happens in a greater diversity of genre-related contexts and collaborative settings—and with a variety of creative goals and desired results—my focus leads away from the creative human being with its agency and knowledge. Instead, it leads toward the creative activity and what is created itself: the entanglement of creative activities and all their traces. I therefore propose a modified topography that includes all the components Zembylas and Niederauer have found, but highlights those that allow reflection on the evolving relations among the participants while interacting and in relation to the resulting musical Geschehen.

- An alternative appropriate term for the participant would be Latour’s actor who interacts with other actors and actants in an evolving network (Latour 1996, 7). However, I chose to keep the term ‘participant’ to highlight the embeddedness in the situation. When referring to any human participant of a creative situation, I use the third-person pronoun they and its respective forms as a gender-neutral alternative in order to respect gender plurality.

- A thorough discussion of this issue exceeds the purpose of this text, but it should be mentioned that this dichotomy of the participant and their "outside" world is only made for analytical reasons. I am aware of reality’s fuzziness and the resulting inseparability of such notions: the individuals are pre-structured and continuously formed through their interaction with the surroundings.

- “This web of expertise functions as a kind of dynamic artistic background, an internalised and integrated whole on which the artist relies for his or her creativity. It is constituted by five dimensions that refer to the complex interactions and exchanges between the musician and his or her environment: embodied know-how, personal knowledge, the environmental, the cultural-semiotic, and the receptive dimension. Together they form a ‘web’ of artistic practice, woven repeatedly by the artist over multiple periods of education, exploration, and performance, offering a solid but agile support and augmenting artistic expertise” (Coessens 2014, 69).

- Some of the introduction’s exercises are inspired by teachings of Kristín Guttenberg and Ingo Reulecke. I experienced these mainly between 2019–2021 through interdisciplinary workshops and meetings for artists working with sound and/or movement, organized by the Berlin-based The Moving Academy. Another source of inspiration was my audio score Human Bodies in Motion (Flick 2023a).

- This is also described by Nancy (2002, 18; 2007, 69) and by myself (Flick 2020, 6–7; Flick n.d., in preparation).

- Rosa distinguishes between four characteristics of resonance: firstly, “being affected” or “reached, touched, or moved” by something or someone (Rosa 2020, 32). Secondly there is the own response to what has affected one; one experiences “self-efficacy,” leading to what Rosa calls “[a]daptive transformation” (ibid., 34). However, the fourth category of “uncontrollability” shows how we cannot plan for resonance to happen (ibid., 36–39).

- See also Vincent Meelberg’s conceptualization of “sonic touch” within his proposition of understanding improvisation as a tactile practice (Meelberg 2022, 20–22). Of interest is the connection between the tactile and the explorative dimension: “Touch connects bodies, minds and also sounds. It creates identities, musical and otherwise. And through touch, these identities are constantly formed, reformed and communicated. This account again confirms that touch is exploratory. Touch depends on improvisation, on in-the-moment actions and reactions, a process that is exemplified in musical improvisation” (ibid., 26).

- By “instant chord” I refer to the structure that evolves when a group of singers or instrumentalists sings or plays, either conducted or self-organized, homophonically with individual spontaneous choice of pitch.

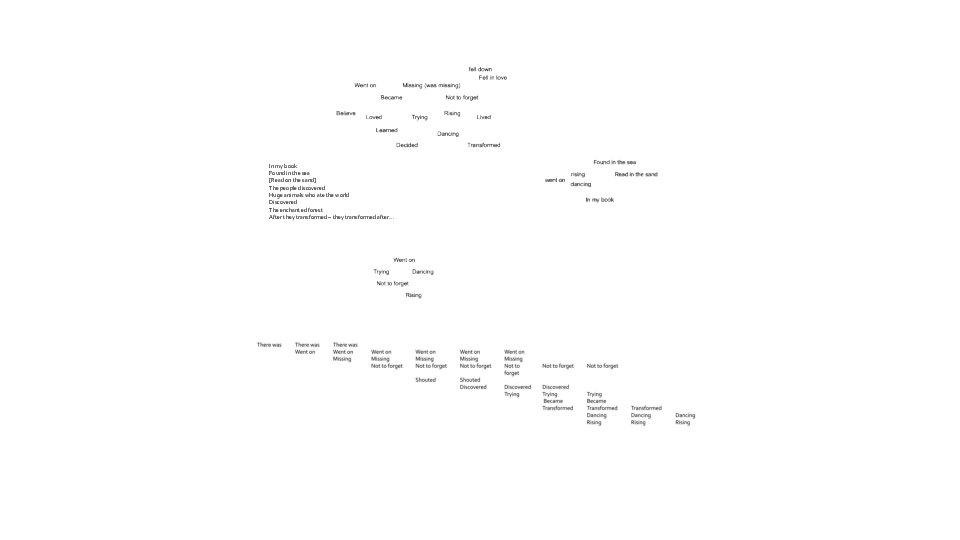

Storytelling

Another important part of the workshop was the experimentation with interaction through language. I had chosen the topic forest as a context for our exercises. For example, a story had to be created by incrementally adding words. Following the clockwise order around the circle we were sitting in, one had to add the first word or a group of words that came to mind and that fit grammatically. The result was a humorous story about the disastrous life of a witch in the forest. This exercise pre-structured the interaction by organizing the order of expressions, by giving a new set of rules (grammar), and through the semantic context (forest). Yet, once again, the crucial tool was listening. The singers’ listening enabled relating temporally and semantically both to the musical Geschehen and to each other.

Expectations

The aforementioned exercise made particularly clear how meaning-making through listening is automatically directed backwards: when listening, there is always a tension between the not yet accessible “possible meaning” (Nancy 2007, 6)12 and the resulting tacit or explicit expectations of any listening, thus contributing to the exercise’s fun. This tension is especially relevant when considering the processes of translation and transformation—implied in the project’s design—between the collective and individual parts of our creative trajectory.

From workshop to score

Only in the individual process of creating the score, I noticed my tacit expectation of how Musa Horti’s text creation in the workshop would inevitably resonate with me. I noticed how I had assumed to be setting text given by the singers to music, including transcribed musical material. However, although I loved the story that the choir had created, it was—in Rosa’s words—uncontrollable for me as a composer. Seeking for resonance, I instead started my work by engaging in awareness training similar to the one Musa Horti had received: sounding the musical space they had created, and trying out different contact modes through listening with different foci to recordings of the singers’ activities from the workshop. Eventually, the basis for the piece was formed by the felt resonance of the emerging relational dimensions. I created a score by synchronously developing text and sound, semantic meaning and the musical course. The following sections show examples of how the happenings of the workshop were translated.

Score

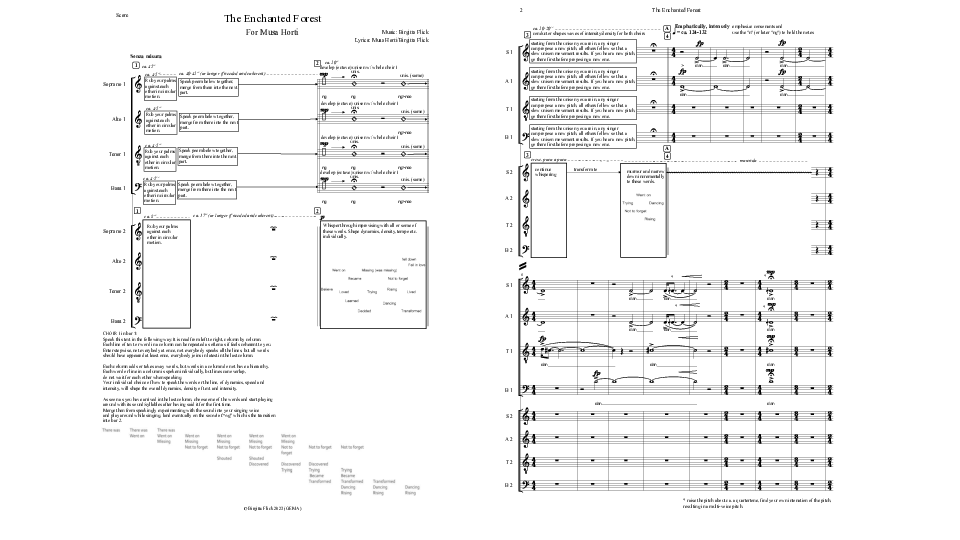

The piece starts from the common sound of all singers rubbing their palms in circular motion, each using their individual tempo. Peter Dejans’ and my formulation of the piece’s basis became part of its preamble: “Everything you do is a result of your listening to yourself in relation to each other. Thus, what is made audible from each singer is of course important, but most important is your listening relationship and attitude towards the group” (Flick 2023d).

Movement through structuring

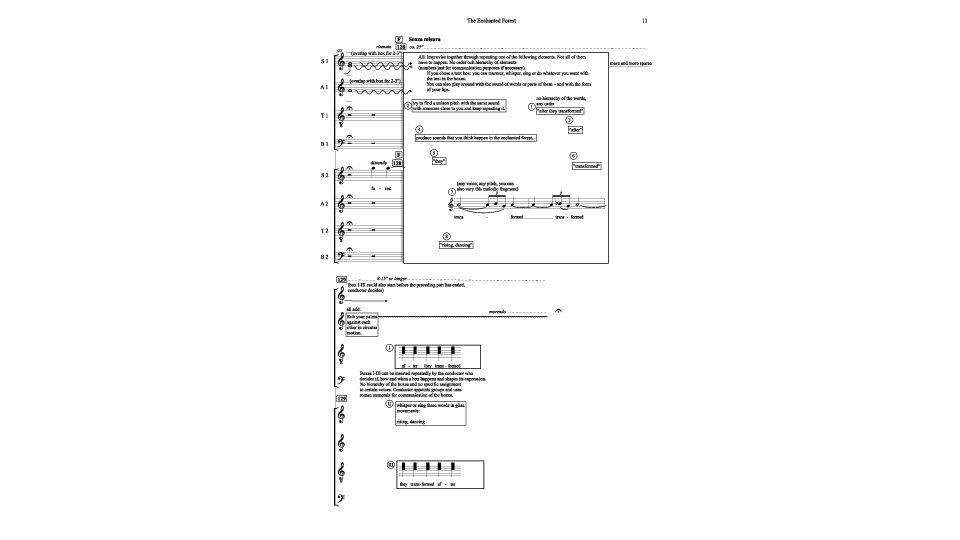

Sparked by the structuring that happened during the unison exercise, I maintained the idea of structuring through movement. However, instead of the singers moving through the space, the sound now moves through a constant restructuring of the choir’s groups. An inner and an outer choir act as a basic structure for the piece. The unison attuning itself became an important tool in the piece, for instance in the beginning in bars 2–3 of choir I (Fig. 4).

The conductor

When comparing the musical Geschehen that had evolved in the workshop with the interaction involving the score, the reappearance of the conductor’s function constitutes, in most cases, a significant difference. Since the piece’s improvised parts are embedded in a completely through-composed course, Peter Dejans’ overall role does not change compared to the choir’s usual repertoire. Still, the constant regrouping, along with the entanglement of conducted and self-organized Geschehen, leads to a continuous emergence of varying modes of relating to each singer, something that needs to be scrutinized on another occasion. Only in the very end of the piece is the conductor involved in the groupings of the choir and invited to decide if, how and with whom to insert sound and text material in the collective palm sound that ends the piece (Fig. 7).

Summary

Our project has highlighted how the activity of listening enables both the establishment and the shaping of manifold modes of relationship among participants of creative situations. This also goes for phases of transition between different parts of the creative process, i.e. collective and individual phases. Fig. 9 complements the topography I sketched in the beginning of my reflections.

Understanding listening as an ongoing contact process makes clear how listening to oneself and to others cannot be separated, neither tactilely-aurally, nor sociologically. Highlighting the transformative character of listening with the help of different concepts of resonance and etymological connotations of listening and obeying, I have worked out how listening engenders what Donald Schön describes as transactional:

The inquirer’s relation to this situation is transactional. He [sic!] shapes the situation, but in conversation with it, so that his own models and appreciations are also shaped by the situation. The phenomena that he seeks to understand are partly of his own making; he is in the situation that he seeks to understand. (Schön 2017, 150–151)

Through shaping and training a tool such as listening, we shape and transform ourselves, the creative situation we are in, and ultimately that what is created.

Credits

Artistic participants:

Musa Horti conducted by Peter Dejans13 & Birgitta Flick14

Video, including video snippets, of The Enchanted Forest:

Dries Verheyen (video, audio recording), Benjamin Geyer (audio mix), Lieven de Geetere (audio recording). Recorded live at Sint-Pieter en Pauluskerk, Grimde, February 1, 2024.

Full video: see Fig. 10 (below).

- Musa Horti: https://musahorti.be (Accessed 2025-09-29)

- Birgitta Flick: http://birgittaflick.com/ (Accessed 2025-09-29)

References

- Coessens, Kathleen. 2014. “The Web of Artistic Practice: A Background for Experimentation.” In Artistic Experimentation in Music: An Anthology, edited by Darla Crispin and Bob Gilmore. Orpheus Institute series.

- Flick, Birgitta. 2020. Du har lärt mig att lyssna: En undersökning av genomsläpplighet i kompositon. Master thesis, KMH Stockholm. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:kmh:diva-3500 (Accessed 2025‑09‑29).

- Flick, Birgitta. 2023a. Human Bodies in Motion. Unpublished audio score, 2023‑04‑28.

- Flick, Birgitta. 2023b. Proposal for a composition collaboration, June 2023. Unpublished manuscript, 2023‑06‑07.

- Flick, Birgitta. 2023c. Workshop script for Musa Horti. Unpublished manuscript, 2023‑09‑03.

- Flick, Birgitta. 2023d. The Enchanted Forest.

- Flick, Birgitta. n.d., in preparation. Refiguring composition: artistically researching the contact between composition, improvisation, and the outside world. Doctoral dissertation, mdw Vienna.

- Latour, Bruno. 1996. “On actor-network theory. A few clarifications plus more than a few complications.” Soziale Welt vol. 47: 369–381. http://www.bruno-latour.fr/sites/default/files/P-67%20ACTOR-NETWORK.pdf (Accessed 2025‑09‑29).

- Meelberg, Vincent. 2022. “Improvising Touch: Musical Improvisation Considered as a Tactile Practice.” In Artistic Research in Jazz: Positions, Theories, Methods, edited by Michael Kahr. Routledge.

- Nancy, Jean-Luc. 2002. A l’écoute. Galilée.

- Nancy, Jean-Luc. 2007. Listening. Translated by Charlotte Mandell. Fordham University Press.

- Noë, Alva. 2004. Action in Perception. MIT Press.

- Noë, Alva. 2010. Out of Our Heads: Why You Are Not Your Brain, and Other Lessons From the Biology of Consciousness. Hill & Wang.

- Rosa, Hartmut. 2020. The Uncontrollability of the World. Polity Press. ProQuest Ebook Central (Accessed 2024-10-12).

- Polanyi, Michael. 2002. The Tacit Dimension. University of Chicago Press.

- Schön, Donald A. 2017. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Routledge.

- Zembylas, Tasos, and Martin Niederauer. 2019. Composing Processes and Artistic Agency: Tacit Knowledge in Composing. Routledge.