Aesthetic influences

The saxophone, being a relatively modern instrument (the birth of the sax dated between 1840 and 1860), was not originally present in the traditional music of Eastern Europe and the Middle East. However, thanks to the saxophone's exceptional expressive capabilities, its relative ease of performance, and its ability to imitate the human voice and other pre-existing instruments, the saxophone has slowly made its way into various traditional musical genres in modern times, sometimes assuming a leading role. There are, in fact, a few examples of a 'stylistically native' musician in one of the sub-genres of makam-music who used the sax as his main instrument.

I will report below only four cases taken as a reference: Samir Srour (Egypt), Ferus Mustafov (North Macedonia), Yuri Yunakov (Bulgaria), Elmas Mamudoski (North Macedonia).

In the links provided, it is possible to have an idea of the expressive capabilities of the saxophone within the makam-music aesthetic. It is possible also to note the wide palette of timbres, articulations and phrasing that different musicians, with different backgrounds, use on the instrument.

Alf Layla wa Layla – Samir Srour

These examples highlight how the saxophone can embody distinct regional aesthetics while maintaining its expressive versatility within the makam idiom.

Adapting microtonality on the saxophone

Adapting a certain style on an instrument means being able to render on the instrument all the characteristics peculiar to the chosen style. Of all the technical characteristics of makam-music, surely the most technically complex on an instrumental level is the use of microtonality. Being able to perform microtones, as performed in traditional makam-music, on the saxophone will certainly represent an important step forward in the adaptation of makam-music on this instrument.

The saxophone originated in Belgium between 1840 and 1860 and was conceived and designed to perform Western music with tempered intonation. Moreover, the saxophone's holes, unlike the flute, clarinet and zurna, are all covered by keypads. This makes it impossible to change the pitch of a note by partially closing the holes. However, it is possible to perform microtonality on the saxophone and many studies have already been done on the subject.

Hayden Chisholm, a pioneer in the use of microtonality on the saxophone, stated in an initerview: “I think the saxophone can adapt very very well to quarter-tone production. I think it can adapt even better than other wind instruments. There are reasons: tuning a saxophone is difficult anyway, there are a lot of compromises to be made, and these can vary depending on the instrument we play. To begin with, we have a lot of keys, so there are a lot of possibilities for key combinations that give us a very good start in microtonality. It seems we are still at the beginning of this research and there is still a lot of work to be done, but I think a lot of progress has already been made on our instrument in the last 20 years.” [Mac Erlaine, 2009].

In other styles, such as jazz and blues, saxophonists have always used microtonal nuances, such as blue notes. In the jazz tradition, the saxophone's potential freedom of intonation is a quality that many jazz players take full advantage of. As in the case of Turkish music, jazz saxophonists, in an extension of American blues music, try to recreate the nuances and emotional range of jazz and blues vocalists by also using microtones [Mac Erlaine, 2009].

Again Hayden Chisholm, when asked: "Do you see microtonality on the saxophone as a device to replicate the nuances of vocal technique more closely?" replies: "Yes, I think it is. I have always aspired to get closer to the nuances of the human voice and as instrumentalists I think we all should. It's one of the advantages we have as saxophonists [Mac Erlaine, 2009].

Microtonality and melodic nuances are a fundamental stylistic component of all Turkish and Arabic music. As Kudsi Ergüner says: “There have been two different paths, in the East a natural evolution that follows acoustic rules and in the West an evolution that required compromises in order to have polyphony. But when you play a pure melody on the piano, without harmony, it has no texture, no taste, because the intervals are all the same (or multiples of each other). Westerners have the idea of the absolute sound - A is A - without relating it to the other degrees of a system. But a sound that is conceived as unique, static and context-free is not rich enough and is not multiple enough. Only by thinking that intervals and notes exist only in relation to other intervals and other notes does sound become something else, another idea. I like to make a metaphor: if you are a painter and you look at nature, you will observe infinite shades of green. If you only classify greens into dark green and light green you will lose all the other nuances. In the Western musical idea there is only dark green and light green. In the melodic idea of Makams, each interval has its own identity, which can be evaluated in the context created by the whole system of Makams and the other Makams. There is no absolute sound.” [K. Ergüner, 2025, Personal communication].

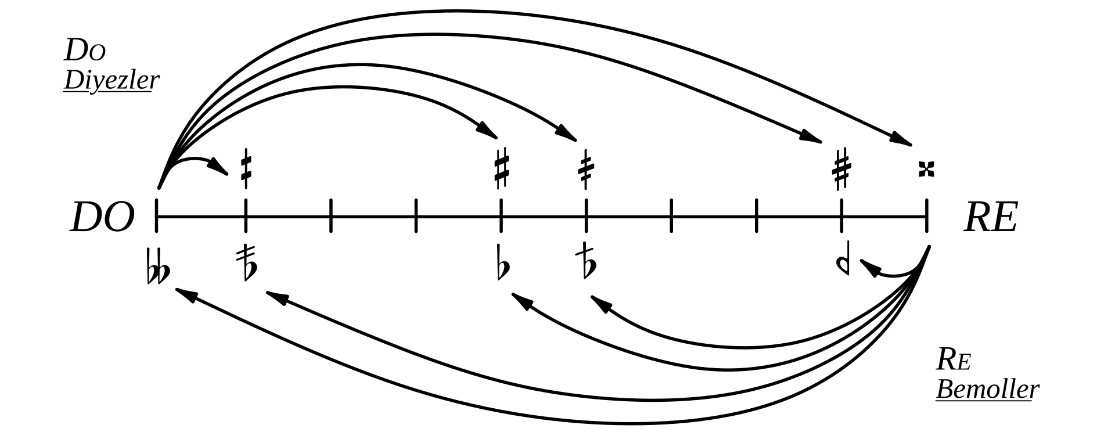

When discussing microtonal music, it is important to refer to the various microtonal theories that have been developed over time. Numerous microtonal theories have been developed in the context of contemporary Western music, however, in the context of this research, only traditional microtonal theories will be taken as reference. The two traditional microtonal systems that I will take as reference are Arel-Ezgi-Uzidilek's "24 non-tempered note system" used in Turkish music [Aydemir, 2010], and the "Quarter tone system" used in Arabic music [Maqam World].

The following figure shows the notes in the quarter-tone microtonal system used in Arabic music (Ex. 2).

In general, there are two completely different approaches to achieve microtones on the saxophone: using alternative fingerings or modifying the tension of the mouth and lip muscles to act on intonation, I will call the latter technique the ''bending technique''. I will investigate these two approaches in detail in the following paragraphs.

Alternative Fingerings

This approach consists of developing a new technique on the saxophone for the use of alternative fingerings for microtonal notes alongside normal fingering. The pure use of this technique involves relying exclusively on alternative fingering without changing the set-up of the mouth.

The main pro of this approach is that although learning alternative fingerings is a difficult process and requires a lot of time and study, once you become confident with the new positions, it is relatively easy to achieve microtones. This technique is particularly useful in fast melodic passages. As A. Simu says “The more music demands quick movements, the more you try to rely on something mechanical like alternative fingerings.” [A. Simu, 2025, Personal communication].

The cons of this approach are various. First, the emission of notes with alternative fingerings is very different from the emission of normal notes, and in general the timbre is altered a lot. The harmonic content of the tone is reduced, and this results in poorer quality. The sound obtained with alternative fingerings is generally a darker or duller sound. Alternative fingerings tend to produce sound inconsistent with the characteristic timbre of the instrument [Paulson, 1975], [Vandegraaf, 2018]. These deviations can be minimised to some extent by adjustments in the player's emission (adjustments in the embouchure and oral cavity), but this requires a great deal of familiarity with the technique [Paulson, 1975].

Another problem is that the pitches obtained with alternative fingerings do not always agree with the pitches theoretically calculated in the systems above, or with the microtones usually found in the repertoire [Paulson, 1975].

Another limitation of the alternative fingerings approach is that these alternative positions are very "individual", i.e. they depend strongly on the type of instrument used, the type of materials (mothpiece and reed) and the performer [Paulson, 1975], [Vandegraaf, 2018], [Mac Erlaine, 2009].

But surely, the biggest problem is the fact that microtones obtained exclusively with alternative fingerings have a fixed pitch, while, often, in makam-music many microtonal notes have and must have a movable pitch. In fact, according to makam theory, there are certain notes known as ''movable notes'' whose pitch is strongly influenced by the melodic context. Thanks to an effect called "ascending-descending attraction" or "diatonic behaviour", movable notes are played sharper in ascending melodic contexts and flatter in descending melodic contexts, and this is not possible using only alternative fingerings. As the clarinetist Caner Malkoç says: “even within a single makam, microtones can change dynamically during the execution, a good example of this is the relationship between Acem and Eviç perdes. Because of this, it is generally better to rely on the embouchure control, allowing the musician to adjust the pitch in real time according to what the ear perceives as necessary.” [C. Malkoç, 2025, Personal communication].

The use of alternative fingerings, without bringing the use of mouth muscles into play, tends to be a more common approach in contemporary music and microtonal jazz, where stable intonations are preferred at the expense of melodic nuances.

I personally know of some alternative fingerings and make use of them. The alternative fingerings I use can also be found in the literature [Paulson, 1975], [Mac Erlaine, 2009], [Vandegraaf, 2018]. However, I always use the alternative fingerings with an appropriate correction of the pitch and timbre made with the bending technique.

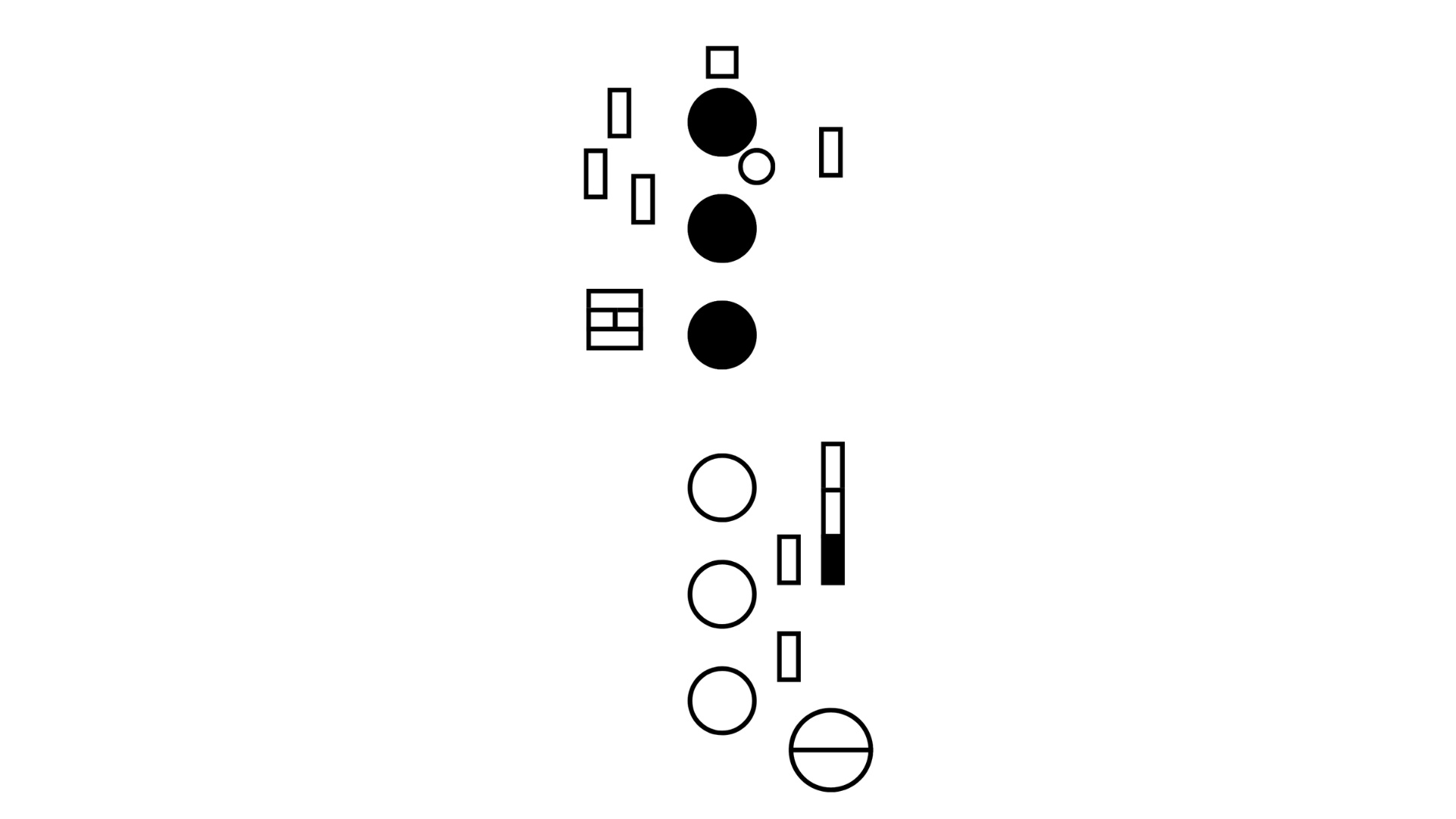

To talk about the alternative positions on the alto sax, I will refer to the diagram in Figure 2, which shows a schematic representation of the sax keys (from the point of view of the performer) with their names.

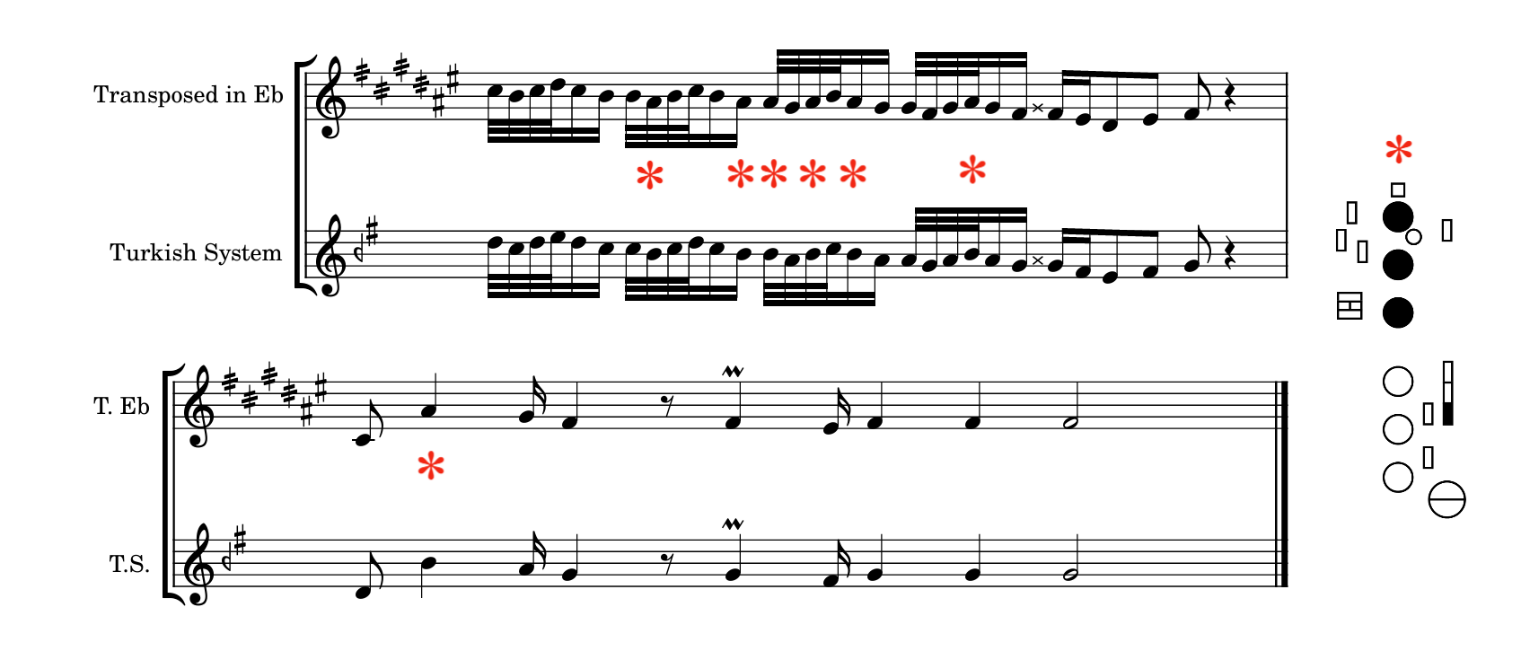

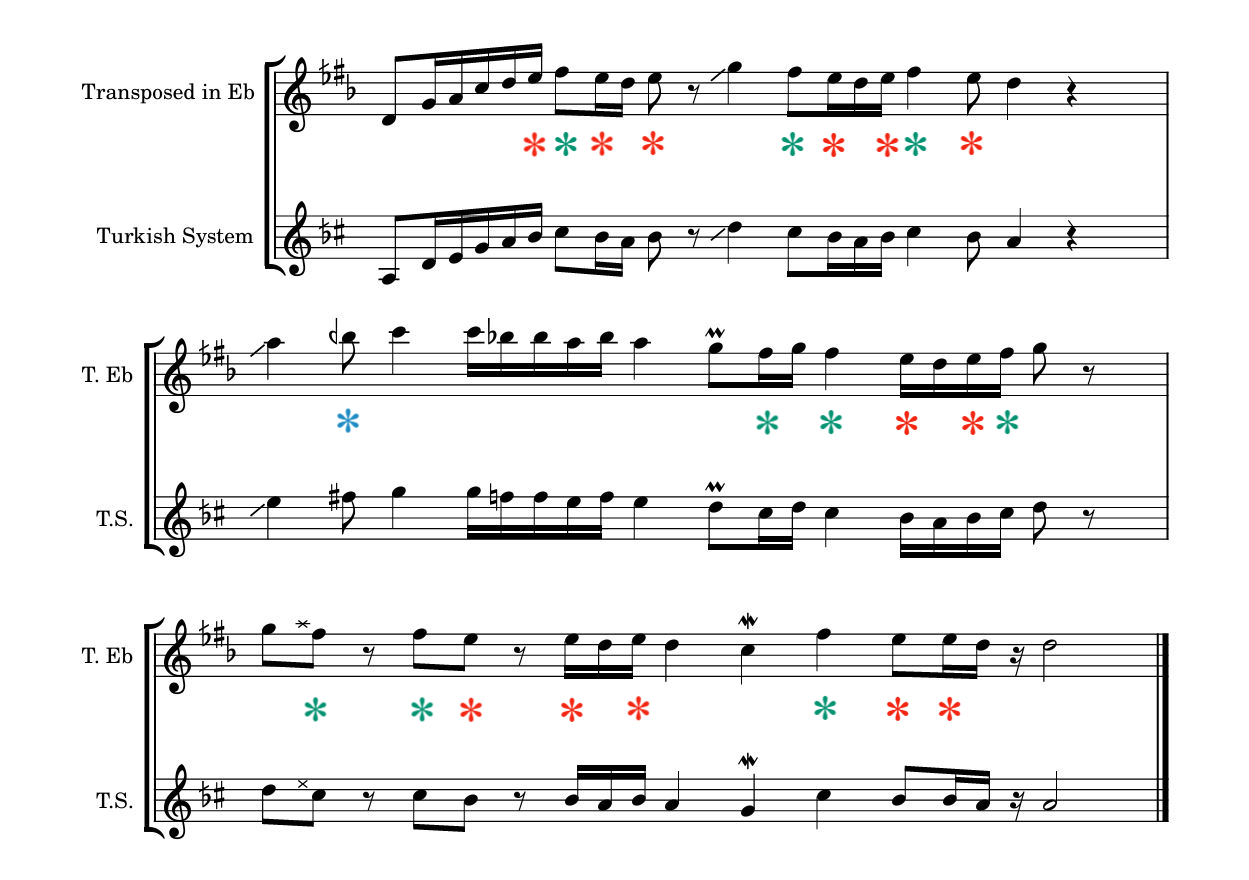

In the following slideshow there is a fingering chart of the alternative fingerings I use on the alto sax. Above the notes on the score is the pitch in cents foreseen by the Turkish and Arabic systems (in this chapter I will write the note names transposed to Eb, as they are called on the alto sax). Next to the figure of the alternative position is the intonation obtained from the test, with reference to the upper and lower notes. References of the same alternative positions in the literature are also shown. The red boxes indicate the function I use most for each alternative position. The sax that was used for testing is a Conn from the year 1919. Pich measurements were made with the Android App “T1”. To perform the measurements, I checked the pitch of the nearest tempered note (without using alternative fingering) so that it was perfectly in tune. I then played the alternative position taking care not to make any movement of the mouth, i.e. without using the bending technique.

In general, the timbre obtained with these alternative positions is consistent with the natural timbre of the saxophone and thus these microtonal positions can be used in a melodic phrase with timbre continuity.

These microtonal positions can be used in both octaves of the saxophone. The only thing that changes between the two octaves is the extent of the bending required to correct the pitch to the desired one.

Positions 1 and 2 are definitely the ones I use the most. Furthermore, I have personally observed other musicians such as Denis Shavlev and Ahmed Redzeposki, whom I will discuss later, use this position.

I use position 1 (and 2) (slideshow) to perform Segah perde in Uşşak makam on the E note and to perform Dik Kürdi perde in Hicaz makam on the E note. In an Uşşak context I still have to use the bending technique to lower the pitch of the note from about F+53/F+61 cents to approx. F+35 cents (In the Uşşak makam, the Segah perde is played lower than the same perde predicted by theory. The pitch of this note depends strongly on the sensitivity of the performer). Also, in an Hicaz context I have to use the bending technique, this time more intensively, to lower the pitch from about F+53/F+61 cents to about F+22 cents.

In the video on the side there is a performance of a melodic fragment in makam Uşşak on the note E. From the video it is possible to see the use of the alternative position 2. Example 3 shows the transcription of the melodic fragment. In the transcriptions, I marked with the red star the notes where I use alternative fingering.

In the video on the side there is a performance of a melodic fragment in makam Hicaz on the note E. From the video it is possible to see the use of the alternative position 2. A transcription of the melodic fragment is shown in Example 4.

I use position 3 (and 4) (slideshow) to perform Segah perde in makam Rast on the note F#. Generally, to perform Segah perde in makam Rast I do not use alternative positions when I want to obtain a pitch more similar to that in the Turkish system. In fact, a pitch of -22 cents is easily achieved only with the bending technique. However, when I want to obtain a pitch more similar to that expected in the Arabic system (-50 cents), I sometimes use alternative positions, as Segah perde has a lower pitch.

In the video on the side there is a performance of a melodic fragment in makam Rast on the note F# using an intonation similar to the Arabic system. From the video it is possible to see the use of the alternative position 3. Example 5 shows the transcription of the melodic fragment.

I use the position 5 (and 6) (slideshow) to perform Dik Kürdi perde in Hicaz makam on the A note.

In the video on the side there is a melodic fragment in makam Hicaz on the note A. From the video it is possible to see the use of the alternative position 5. A transcription of the melodic fragment is shown in Example 6.

I use position 7 (and 8) (slideshow) to perform Segah perde in Uşşak makam on the note B, to perform Segah perde in Rast makam on the note A (with Arabic intonation) and to perform Dik Kürdi perde in Hicaz makam on the note B. In an Uşşak context I have to use the bending technique to lower the pitch of the note from about C+45/C+60 cents to approx. C+35 cents. In an Hicaz context I have to use the bending technique, this time more intensively, to lower the pitch from about C+45/C+60 cents to about C+22 cents.

In the video on the side there is a performance of a melodic fragment in makam Uşşak on the note B. From the video it is possible to see the use of the alternative position 7. A transcription of the melodic fragment is shown in Example 7.

In the video on the side there is a performance of a melodic fragment in makam Rast on the note A (with Arabic intonation). From the video it is possible to see the use of the alternative position 7. A transcription of the melodic fragment is shown in Example 8.

In the video on the side there is a performance of a melodic fragment in makam Hicaz on the note B. From the video it is possible to see the use of the alternative position 7. A transcription of the melodic fragment is shown in Example 9.

Of the above positions, positions 1 and 2 (slideshow) are used much more than all the others. As can be seen from the transcritpions above and the videos shown, in some melodic contexts it is convenient to use some specific alternative fingerings, but in any case, the use of alternative fingerings must be coupled with the use of the bending technique to achieve the desired intonation. In general, descending bendings are used much more than ascending ones.

In the sources consulted ([Mac Erlaine, 2009], [Paulson, 1975], [Vandegraaf, 2018]) there are microtonal fingering charts for all microtonal notes throughout the whole saxophone extension. Apart from the eight alternative positions which I also use, I find it unnecessary and forced to study the other positions for applications in makam music. In fact, many of the proposed positions are associated with a microtonal note that, although present in microtonal systems, is not used in most makams. Others are positions to obtain common perde-s but in transpositions rarely used. Positions in extremely high or extremely low ranges of the sax will be used infrequently and will be very difficult to use. Some of the proposed positions produce a note with a pitch too different from that required by the specific makam. Some of the proposed positions produce a note with a poor timbre that is not consistent with the natural timbre of the sax.

Microtonal Bending Technique

This technique consists of obtaining microtonal notes by changing the sound emission. To do this, all the muscles of the mouth, lips and oral cavity must be used. It tends to be easy for reed instruments to lower the pitch of a note by decreasing the pressure exerted by the muscles on the reed. To do this, one must generally lower the jaw and decrease the tension on the lower lip. The effect and extent of the bending produced depends very much on the position of the note in the range of the instrument, but in general it is possible to get the note out of tune by an interval varying between a semitone and a minor third (sometimes even a major third or a fourth can be reached) [Mac Erlaine, 2009]. An opposite effect can be obtained by increasing the tension on the reed. This increases the pitch of a note, but the magnitude of this effect is much less; therefore, this technique tends not to be used. Therefore, to obtain a microtonal note on reed instruments, one can use the position of the upper tempered note and detune it to the desired pitch.

This type of technique and the microtonal deviations (often referred to as tonal shadings or colourings) obtained with this technique are common to much vocal and instrumental music outside the Western tradition. In terms of their expressive capabilities, saxophonist Hayden Chisholm considers them embellishments that “encapsulate a melody or note into something beautiful”. It is as if, instead of laying things bare, they present them with greater subtlety, as something more fragile [Mac Erlaine, 2009].

The main pro of this technique is that it is possible to change the intonation of a note ''continuously''. This allows more intonation possibilities, which can be used in different contexts, allows more melodic nuances and allows glissandi to be played. In addition, with this technique one can actually play the ''moving notes'' with varying intonation required in makam-music. As Ünsal Çeliksu says “The bending technique works every time if you learn it properly. It works on every note and every makam. It also works on the so-called "moving notes", when they require the pitch to be changed during the note itself [Ü. Çeliksu, 2025, personal communication].

The cons here are also various. Firstly, changing the set-up of the mouth certainly brings timbre changes, and usually the timbre becomes poorer. However, these timbre deviations can be minimised by the performer after careful study. Surely the most difficult aspect of this technique is the fact that it is difficult to know ''where to place'' the microtone. And in this case the ''where'' essentially represents a point on a scale of ''pressure'' of the lip on the reed. This is a very strong limitation, especially for ''stylistically foreign'' musicians, as for them, the position of the microtones is often not clear, and a new ear training is required before the training of the muscles of the mouth to make sure they are clear about the sound they want to achieve. As F. Sierakowski says “The problem with pitch bending is that a beginner can't really do it technically and it sounds a bit clumsy, but it's going to sound clumsy at first whatever you do!” [F. Sierakowski, 2025, personal communication].

Personally, I make great use of the bending technique, especially to lower the pitch of certain notes. In a Rast context I use this technique to get Segah perde (3rd degree) and Eviç perde (7th degree). In an Uşşak context I use this technique to obtain the same perdes (in this case 2nd and 6th degree). It should be noted that in an Uşşak context, Segah perde must be performed lower than the same perde in a Rast context, and this involves more action of the mouth muscles to detune the note. In an Hicaz context I use this technique to obtain Dik Kürdi perde (2nd degree), Nim Hicaz perde (3rd degree) and Eviç perde (6th degree). In a Saba context I use this technique to get Segah perde (2nd degree) and Hicaz perde (4th degree). It should also be noted that when several microtonal notes are close together in the scale, a high degree of control of this technique is required as each note has its own specific pitch and therefore requires a different action of the mouth muscles.

Obviously, this technique is very complex to use and requires a lot of practice. The exercise that has been most useful for me at this stage is to play a note and detune it to the desired pitch. In doing this, one must maintain good control of timbre and dynamics. It is important to check the pitch with a tuner while performing the exercise and to use a metronome.

In the video on the side there is a performance of a melodic fragment in makam Uşşak on the note E. I have not used any alternative positions in this video. From the video it is possible to see how I move my mouth when I need to get a mictone. Example 10 shows the transcription of the melodic fragment. In the transcriptions I marked with a star the notes where I have to use the bending technique.

The red stars correspond to the Segah perde, which in a Uşşak context is played by me at about -65 cents compared to the upper semitone (tempered F#). The blue star corresponds to the Irak perde, which theoretically has a pitch of -11 cents compared to the upper semitone (tempered C#). Thus, the action of the mouth muscles to detune these notes is different for each individual microtonal note.

In the video on the side there is a performance of a melodic fragment in makam Hicaz on the note D. Example 11 shows the transcription of the melodic fragment.

The red stars correspond to Dik Kürdi perde, which theoretically has a pitch of -88 cents compared to the upper semitone (tempered E). The green star corresponds to Nim Hicaz perde, which theoretically has a pitch of -11 cents compared to the upper semitone (tempered F#). The blue star corresponds to Eviç perde, which theoretically has a pitch of -22 cents compared to the upper semitone (tempered B).

As you can see from the videos, the mouth movements, from the outside, are microscopic. And each microtonal note requires different muscle action depending on the intonation one wishes to achieve.

As Caner Malkoç commented about the two previous videos: “Here the microtones sound much more natural compared with the performnces with alternative fingerings. As I mentioned about the alternative fingerings, in these two videos, it is possible to hear the subtle variations within microtones. This prevents musical phrases from sounding artificial, and your flexibility comes across as quite smooth and well-balanced.” [Caner Malkoç, 2025, personal communication].

Comparative Analysis of Performer Approaches

In the following, I will analyse the techniques of various saxophonists and clarinetists, both ''natives'' and ''foreigners'' to understand their approach to microtonal production. With each of them I have had a direct personal experience from which I have produced these observations. In this section I will also analyse clarinetists as the technique of the clarinet is similar to that of the saxophone and therefore observations about clarinetists can be carried over to the sax without any problems.

From my experience there are four types of approaches:

-

Musicians who do not use microtones but mimic microtones with phrasing

-

Musicians who use only alternative fingerings

-

Musicians who use only the bending technique

-

Musicians who mix alternative fingerings with bending

-

Musicians who do not use microtones

Vladimir Karparov (BG):

Karparov is a Bulgarian saxophonist based in Berlin. He received his training in jazz and be-bop and later became interested in traditional Bulgarian music and combining this style with be-bop. Although Karparov is Bulgarian, he can be considered an intermediate figure between ''stylistically native'' and ''foreigner'' in that for him, learning Bulgarian traditional music occurred at an already advanced stage in his career.

I met Karparov in 2023 to have a lesson with him in Berlin.

Karparov tends not to use microtones but their tempered approximation. This is also due to the fact that Karparov's personal styles and bulgarian style are generally played at very high speeds, which sacrifices the possibility of appreciating microtonal nuances. However, in Karparov's compositions, there are aspects of phrasing that ''mimic'' microtonality and the behaviour of moving notes.

Example 12: Bar 3 and 4 of Medina CueCheck by V. Karparov [Karparov]

The phrase shown (Ex. 12) is a phrase in a melodic context of the makam Saba on the note E, but played using its tempered approximation. The F is played sharp in the first bar and at the beginning of the second bar, but is played natural at the end of the second bar when the phrase concludes on the E. This tends to mimic, with the use of tempered notes, an F intermediate between natural and sharp and mimics the ''ascending-descending attraction'' whereby moving notes are played higher in ascending melodic contexts and lower in descending melodic contexts.

-

Musicians who use only alternative fingerings

This is an approach generally used by western musicians, especially in western styles such as contemporary music and microtonal jazz.

-

Musicians who use only the bending technique

Ünsal Çeliksu (TR):

Çeliksu is a clarinet teacher at the İstanbul Teknik Üniversitesi Conservatory in Istanbul (İTÜ), Turkey. With Ünsal Çeliksu I studied clarinet for two years at İTÜ.

As he says about his personal approach “My personal approach is to obtain the microtones for the 90% with the bending technique (blowing koma), because there are no correct alternative fingerings for each microtone in each transposition” [Ü. Çeliksu, 2025, personal communication]. During our lessons he categorically rejected the use of alternative positions. He is very confident with the production of microtones with this technique on all notes of the clarinet and across the whole range.

Manos Achalinotopoulos (GR):

Achalinotopoulos is a renowned Greek clarinetist and clarinet teacher at PAMAK, Thessaloniki.I attended a week-long online workshop with Manos Achalinotopoulos on the clarinet in various Greek folk styles, organised by Labyrinth.

During the workshop, we worked on various makams, and Manos obtained all the various microtonal notes exclusively with the bending technique. In some genres of Greek folk music (e.g. in Epirotika), the bending is used not only to obtain the microtonal notes but is also used a lot as an expressive ornamentation technique. It should also be noted that Manos uses very light reeds on the clarinet, which makes it easier to use the bending technique.

Berke Yiğit Satılmış (TR):

Berke is a Turkish clarinettist of my age, originally from Thrace, but based in Istanbul. I met Berke during my period in Istanbul and took lessons from him.

As far as I saw during the lesson we did on the Uşşak makam, Berke achieves the microtones of the Uşşak makam exclusively with the bending technique, without using alternative fingerings.

Mehmet Ali Orman (TR):

Mehmet is a Turkish clarinettist living in Istanbul who is very active in modern traditional music. He generally plays the G clarinet, a classical choice for many Turkish clarinetists. I met and hung out with Mehmet during my period in Istanbul.

As far as I could see, he only achieves microtones with the bending technique. It should be noted that the bending technique on lower instruments (such as the G clarinet) is probably easier than on higher-pitched instruments (such as the Bb clarinet).

Nazir Alimov (NMK):

He is a saxophonist originally from Štip (North Macedonia) but based in Canada. He is the son of Nizo Alimov, trumpeter of the Kočani Orkestar. I met him in 2021 in Štip while attending a workshop held by his father Nizo and uncle Sercuk. In 2021 Nazir was about 15 years old.

Observing the way he played during the workshop, I realised that, to play a song in Hicaz makam on the note E (transposed to Eb), he would obtain Dik Kürdi perde (High F) by playing the F# position and lowering the pitch with the bending technique. The piece we were playing was a medium-high speed Cocek, so this technique required a lot of control.

-

Musicians who mix alternative fingerings with bending

Alex Simu (RO):

Alex is a Romanian saxophonist and clarinetist who began his study with jazz. He was my saxophone and clarinet teacher for four years.

During my time studying with him we worked a lot on achieving microtones with the bending technique, but we also worked a lot on finding good alternative positions, from the point of view of timbre, comfort and intonation. Sometimes, with Alex, we also worked on the possibility of raising the pitch of a note by increasing the pressure of the lips, an approach that I soon abandoned.

Caner Malkoç (TR):

Caner is a Turkish clarinetist. I met and hung out with him during my time in the Netherlands.

Observing Caner as he plays, I noticed that he is comfortable achieving microtones over the entire extension of the clarinet with the bending technique. However, he often advised me of many alternative fingerings and told me that he also makes use of these alternative fingerings under specific conditions such as a piece played at high speed.

Ismail Lumanovski (NMK):

Ismail is a North Macedonian clarinetist currently based in New York. He is a very famous and renowned musician. I met Ismail during a workshop in 2023 in Brussels.

During the workshop, I asked Ismail directly what his approach was, i.e. whether he preferred to use alternative positions or the bending technique to achieve microtones. He clearly replied that he uses a mix of the two techniques. Not least because alternative fingering will not exactly produce the intonation required by the specific melodic context, so it must be corrected with the action of the mouth muscles. He then showed me some alternative positions for the clarinet, which are especially interesting for achieving a more consistent timbre with the natural timbre of the instrument.

Denis Shavlev (NMK):

Denis is a saxophonist from Strumica (North Macedonia). He is very active in modern Macedonian Roma music and Tallava. I met Denis in 2023 in Strumica during a study trip to North Macedonia, I took lessons from him on Tallava style.

During these lessons, I was able to observe how he produces microtones. It must be said that Tallava is a style where microtonality is used extensively, even on notes that theoretically do not involve it. For example, the fifth degree of the Makam Hicaz (Hüseyni perde) is played slightly sharper. When Denis plays Hicaz on the D he gets Dik Kürdi perde (high minor second, high Eb), Hüseyni perde (high perfect fifth, sharp A) and Eviç perde (low major sixth, low B) invariably playing the position of the semitone above and using the bending technique exclusively. However, when he has to play the Hicaz makam or the Uşşak makam on the E (the Uşşak makam in Tallava is called "Minor") he obtains the second degree (Dik Kürdi perde in Hicaz, Segah perde in Uşşak) of both makams with the same alternative fingering (Alternative Fingerings 1 and 2) and slightly modulates the pitch at will with the bending technique.

Ahmed Redzeposki (NMK):

Ahmed is a saxophonist from Prilep (North Macedonia). He generally plays Tallava. I met Ahmed in 2023 in Prilep on the same study trip in which I met Denis Shavlev and took lessons from him. In 2023 Ahmed was about 15 years old.

The technique used by Ahmed is very similar to that used by Denis, despite the stylistic ''rivalry'' between the Tallava style in Prilep and Strumica.

Fausto Sierakowski (FR):

He is a stylistically 'foreign' musician because he learnt and adapted makam-music on the saxophone at an already advanced stage in his career. I know Fausto personally and have met him many times, we have often played together, and I have taken lessons with him.

I know from direct testimony and the testimony of some of his students that it is very important for Fausto to aim to obtain the microtones of the main makams (Rast, Uşşak, Saba, Hicaz) without using alternative positions. However, in some special cases Fausto also uses other techniques. As he says: “I think all the approaches are useful, both the alternate fingerings, the pitch bending and also some kind of reduction to play tempered tuning on fast phrases, to have speed in the fingers, than using microtonal tuning.” [F Sierakowski, 2025, personal communication].

In general, it can be said that stylistically ''native'' musicians all use the bending technique, sometimes also coupled with the use of alternative positions. The ''native'' musicians closer to the genres of ''art music'', such as the Ottoman style, and away from folk music, are more inclined to exclusively use the bending technique without alternative positions. Musicians interested in other styles, such as microtonal jazz or contemporary music, on the other hand, tend to prefer the use of alternative positions, probably to have a more stable and reproducible intonation.