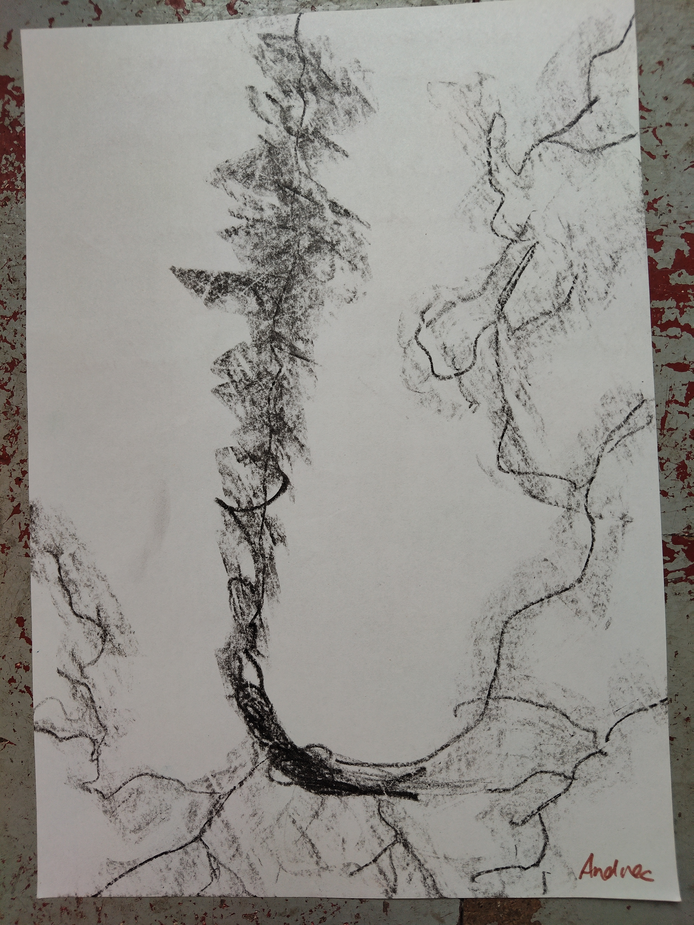

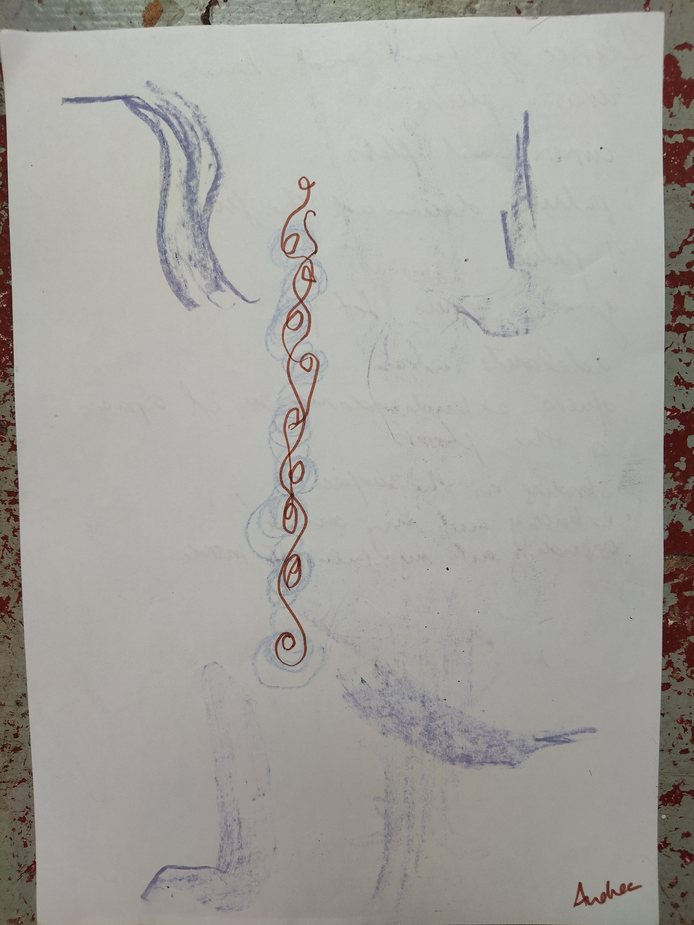

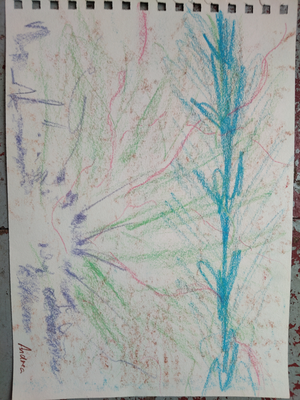

Paying attention to both a thing but also the borders of a thing.

Then paying attention to borders as the encounter or the connection of things

The encounter, contact or the connection doing the creating o consituitng of physical apperaces.

The difficulty of exploring the mental-embodied images in a Skinner Releasing class is not only that it is a subjective experience, but also that it can only be approached retrospectively. This means that a great deal of work goes to how I focus my attention.

Memories: is there a backward motion? Or rather a strong reaching or connecting to something that has a certain existence which can appear. The action or the effort that one does is slightly different. When a memory appears there is perhaps a certain motion of the movement of our focus that “reaches into” rather than springing out.But the expereince is surprising or feels like out of the blue.

What to look for:

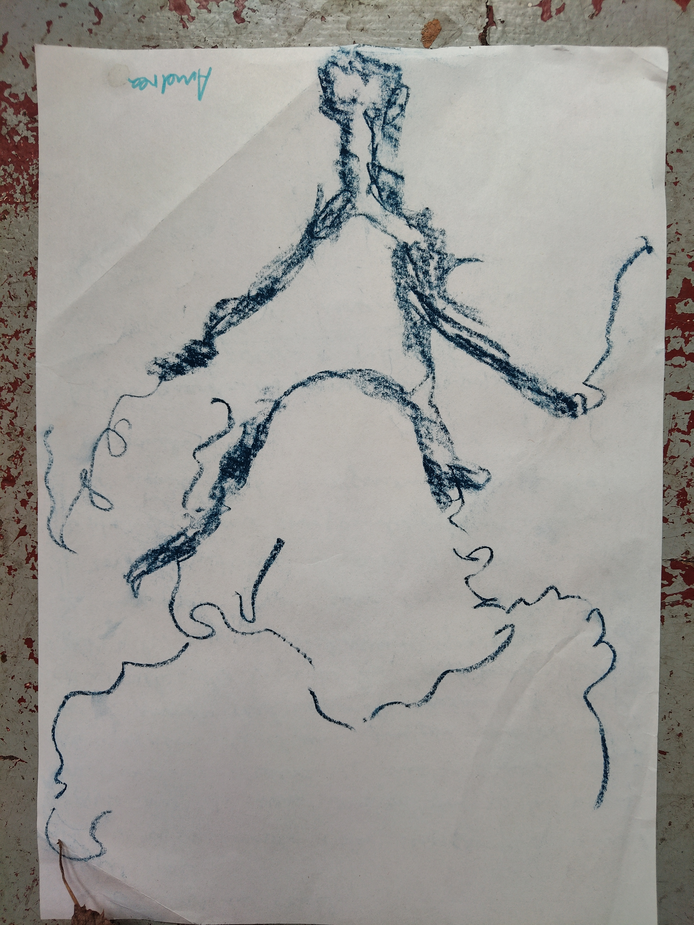

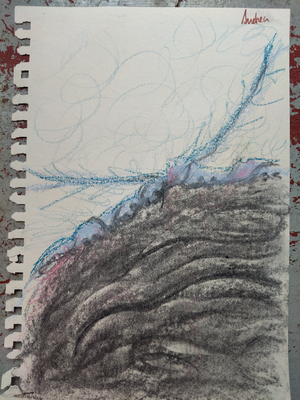

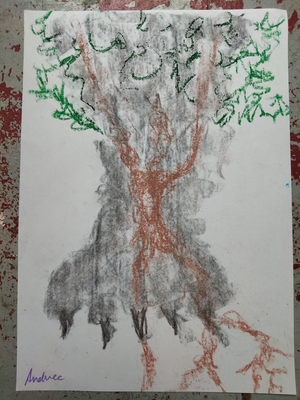

“how do we see the form or shape of a thing?”

“How do we see the motion of a thing?”

“[...] how do we see a thing — the mere object as distinguished from its general background?”

How do we see an outline as separated to its background?”

“how do we see a solid surface?

“Why do things have location, that is, how can we see where they lie?”

“How do we see fine detail, and what are the limits of this acuity?”

“Why do things look right side up?”

“Why does the world always appear level even when we lie down?”

(Gibson, 1950, p.2)

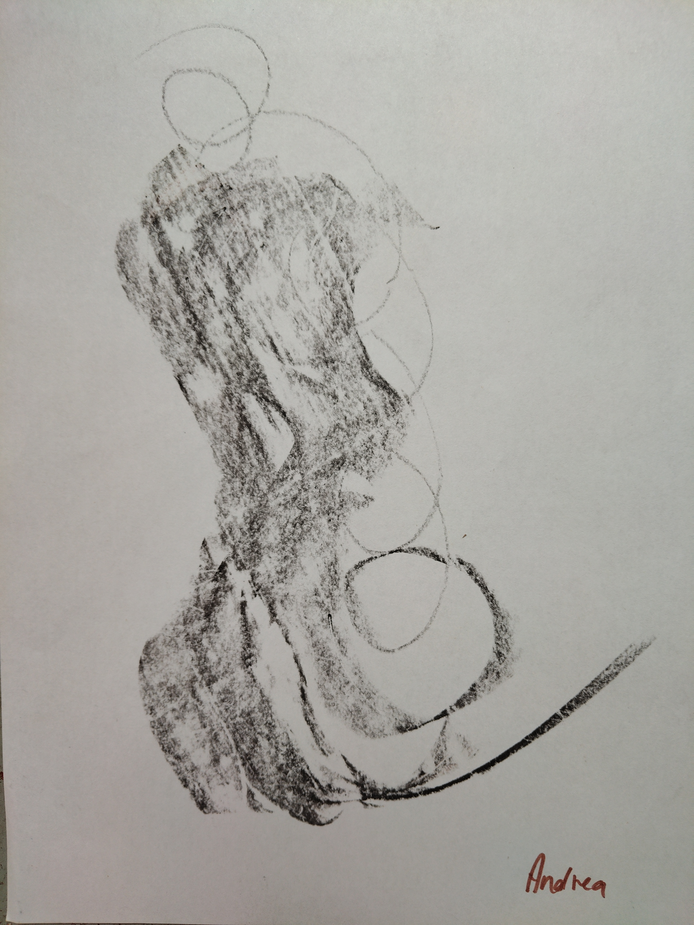

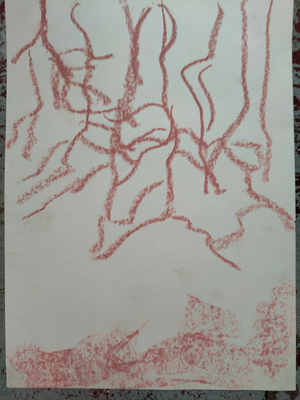

During a Skinner class, when I hear an instruction from the teacher — for example, “transparent threads” — a series of thoughts or image-thoughts spring up. They seem to hover between memories (like a scene of Chinese marionettes in a film I once watched) and imagined images. For instance, I might “see” a spider’s web thread — perhaps from a moment when I once encountered a real web, or perhaps entirely imagined.

When recalling this sort of experience, it is common for the speaker to close their eyes and gesticulate with their hands and arms, sometimes there is movement of the torso or a different way of breathing. It is as if there is an impossibility of ‘thinking about’, perhaps because ‘thinking about’ would reinstate or re-establish the presence of the ‘I’, which automatically separates subject and experience where one is observing rather than being in action. These gesticulations and the closing of the eyes seem to look to find a position in space, as if these movements can let the speaker be immersed again in the moment where their own body disappeared into movement.

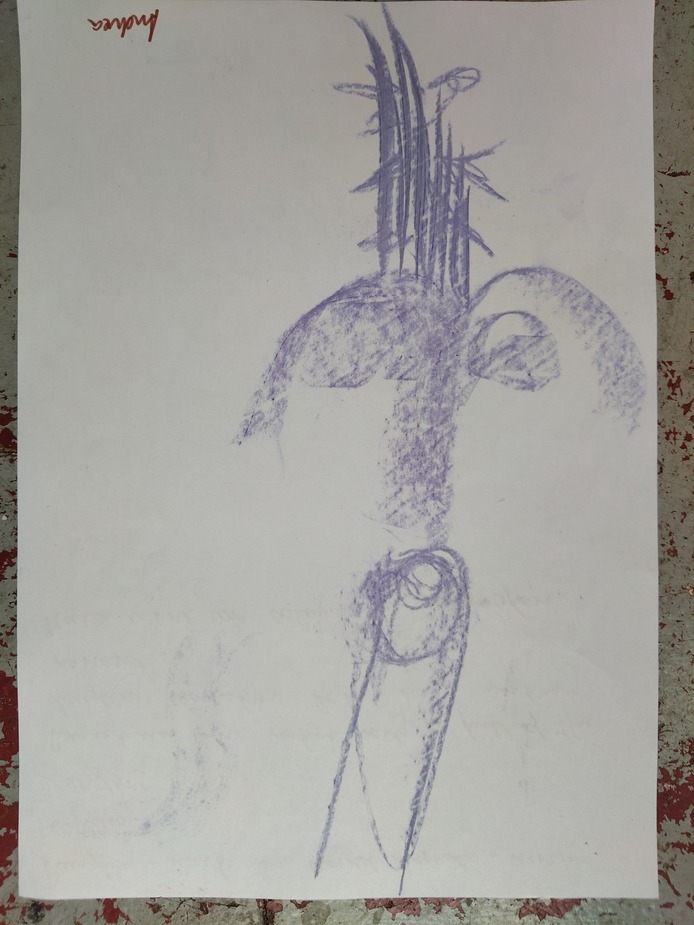

In psychoanalysis, a memory is not bound to a temporality. A memory is not a past experience; it is a present occurrence. However, although memories are present occurrences, they can exist in a less accessible register. Therefore, the question is: does one access this register so that the experience rather than being unearthed from the past is activated as a present occurrence?

The answer lies in no longer believing in the need to be conscious of an object that appears from the reality of an experience. When the “I” is replaced by the presence of a relational field of movement, the concept of subject-object also disappears. Thus, at this moment there is no “subjective experience” of a “mental image” but an activation of this relational field, which is full of its own factual-virtual reality.

This seems to raise the question about imagery and ‘present-ness'…

Elaine Scarry in her book Dreaming by the Book looks at the imagined object in novels not as "representing" or "mimicking" the real world. But rather, that it is our seeing, hearing or feeling of them which is mimetic: "In imagining Catherine's face, we perform a mimesis of actually seeing a face; in imagining the sweep of the wind across the moors, we perform a mimesis of actually hearing the wind." (1999, p. 6)

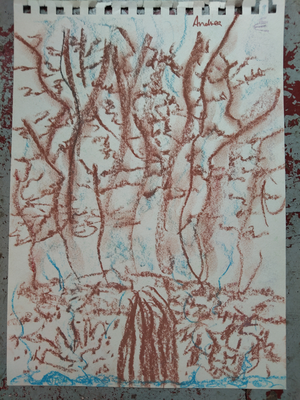

For Bachelard the poetic image has a generative force from a pure beginning as it is detached from a cultural past. However, the poetic image is rooted in a universality anchored in the natural world of which our material existence is part. From this universality, the image reveals itself not as a product of the imagination, but rather, image and imagination are symbiotic, “We do not produce an image because we imagine. Instead, we imagine because of the image.”(Bachelard 1994:166). Concentrating on an image that mediates between the subject and the world, the world opens up anew, with each poetic image in a kind of expanding spiral of image and renewal, ‘Each contemplated object, each evocative name we murmur is the point of departure of a dream and of a line a creative linguistic movement’. (Bachelard cited in Gaudin 2005, p. 23).”

The crucial thing is this "spring up". This "creation" which occurs when a few things are in contact or in relation - the words of the teacher, my imagination and my body.

“The visual world can be described in many ways, but its most fundamental properties seem to be these: it is extended in distance and modelled in depth; it is upright, stable, and without boundaries; it is colored, shadowed, illuminated, and textured; it is composed of surfaces, edges, shapes, and interspaces; finally, and most important of all, it is filled with things which have meaning.” (Gibson, 1950, p. 3)