Reflections on Reflecting

by Lisa Hester

In 2025 I received the Emerging Artist Bursary supported by artsandhealth.ie and funded by the Arts Council and HSE. The award offered protected time to examine my emerging arts practice within arts and health. My original proposal focused on developing a creative programme for children living with long-term health conditions, but once the research began it became clear that I needed to step back further. Before developing new approaches, I needed to understand my own reflective habits: how I interpret situations, document affective experiences, and develop insights that support ethical decision-making in future projects.

If I had been asked six months ago, I would have said that reflection was already part of my work. During this research, however, I realised how informal and ineffective my approach was. I sometimes wrote brief notes after workshops, made instinctive observations, or took photographs of small moments. But these practices were irregular and too inconsistent to offer any real value.

When I began approaching reflection more intentionally, I realised how much of my thinking had gone unexamined. I often moved past experiences before understanding what they could teach me. The bursary allowed me to slow down, look more closely, and treat reflection as an important method rather than a by-product.

This exposition gathers the material found and generated during the bursary and focuses on examining my existing reflective habits within my emerging socially engaged arts practice. The aim is to understand how I have been reflecting up to now, what those habits reveal, and where they may need to change as the work develops. The use of the Research Catalogue is deliberately experimental: an attempt to see how reflective material can be archived and encountered when arranged spatially rather than in a linear report.

The first three episodes revisit earlier moments in my practice.

-

Episode 1: My Fine Art degree show, where I worked with a group of children to create a series of paintings, an early, unrecognised form of socially engaged work.

-

Episode 2: My experience as an activitt coordinator and how that role shaped my approach to care-based environments.

-

Episode 3: Seeds Grant for Arts in Residential Care Settings'; my first funded project.

Together, these episodes helped me identify how I had been reflecting in the past and revealed the limits of those informal methods.

Episodes 4 and 5 focus on the bursary period.

-

Episode 4: An emotionally significant visit to a care home in August, where I applied more structured reflective models.

-

Episode 5: Reflections following a CPD workshop organised by Réalta on boundaries in arts-and-health practice.

The accompanying PDF provides a concise written overview with the broader conceptual framing. This exposition holds the fuller archive; written reflections, photographs, audio notes, and scanned documents. The aim is to present these in a way that makes the reflective process visible rather than summarised.

To begin, use your mouse or trackpad to follow the lines across the page and interact with the different elements as you encounter them. You can zoom in and out using the page controls to help you navigate this digital sketchbook.

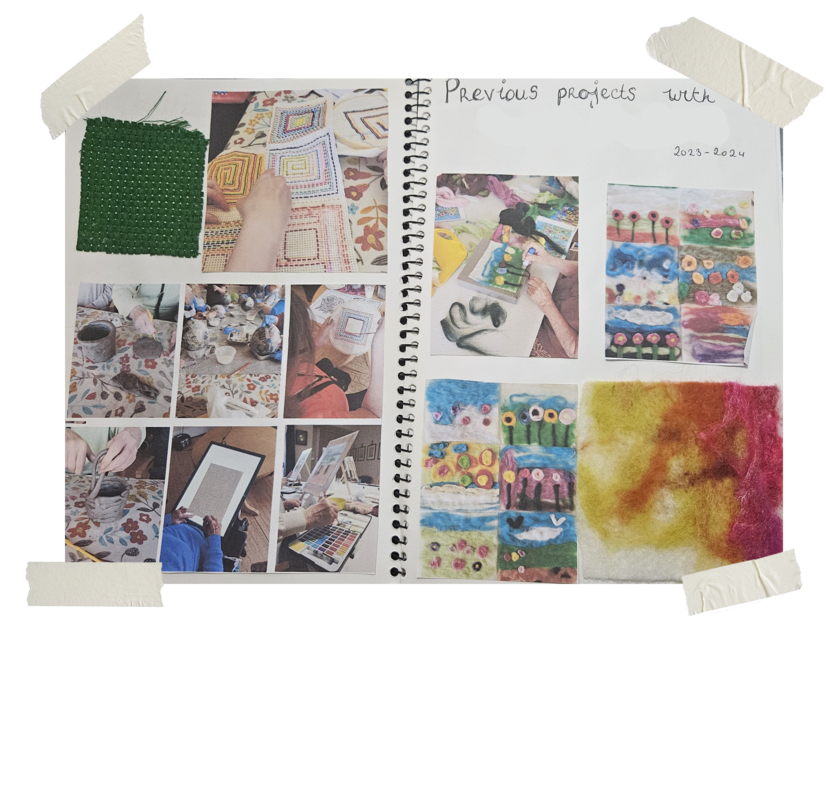

2. Activity Coordinator Role (2023-2024)

I applied for the Activity Coordinator role just after passing my PhD viva, hoping it might be a way explore developing an arts and health practice. I worked in the care facility for nine months, twenty hours a week. When I looked back at the material from that time, I realised how little reflection I had done. Apart from a few photographs and brief notes from one-to-one sessions, there was almost nothing. The work was demanding, and I didn’t yet have the reflective habits or self-care practices to process it properly.

What stands out now is how strongly the care home was dictated by a strict and necessary rhythm. Mealtimes, medication rounds, personal care, visitors, or someone needing rest all shaped the pace. Creative activity had to fit into short, unpredictable windows. After some time, I began to realise that success wasn’t measured in finished artwork but in calm engagement, a few minutes of focus, a small gesture, or someone simply joining in.

I also began to understand how much grounding an artist needs in dementia-informed practice: a person-centred approach, sensory-aware spaces, predictable cues, and small rituals that signal safety and orientation. Elements such as consistency, familiar materials, clear signage, the same lighting or music made the biggest difference. Sessions worked best when they started with looking and moved gently into making, ending with a moment of recognition or appreciation.

Revisiting this time has shown me both the value of the role and the limits I experienced within it. It clarified the realities of care work, the emotional weight carried by staff, and more knowledge on what a creative practice needs in order to be ethical and effective in this environment.

1. Fine Art Degree Show (2019)

Looking back, this project sits awkwardly between studio practice and what would later become socially engaged work. The surface features were there; involvement of others, responsiveness, shared material, but the core elements were missing: no co-authorship, no clear intention, no ethical framing, and no attention to how the children experienced the process. At the time, I treated their contributions as raw material rather than part of a relationship or exchange.

This only became visible when I went searching for documentation and found my final-year folder, which I’d completely forgotten existed (it was under my bed covered in dust). This was a reminder of how quickly I moved on after graduating. I didn’t give myself time to absorb or value what I’d made, and I never really reflected on that period at all. The folder contains process notes and scattered academic reflections, but almost no emotional or relational insight. That gap is telling.

I hadn’t considered the degree show as a step toward socially engaged practice. Looking through the folder changed that. It’s clear now that this was the point where other people’s input began to shape the work, even if I didn’t notice it at the time.

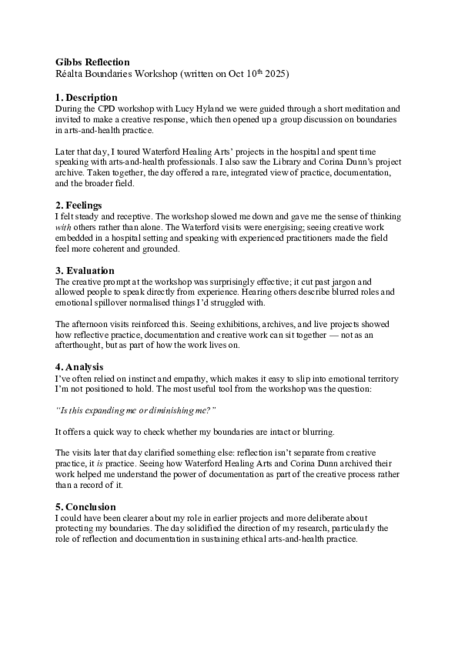

5. Articulating Boundaries (November 2025)

I attended a Réalta CPD workshop led by Lucy Hyland. The session began with a short meditation followed by a creative prompt, which opened an honest discussion about the realities of boundaries in arts-and-health work. Hearing others speak about blurred roles, emotional load, and the pressure to 'hold everything' made the topic feel concrete rather than theoretical.

Later that day, I visited Waterford University Hospital with members of the Waterford Healing Arts team. I saw their current exhibition installed along the main corridor, viewed artwork produced through recent programmes, and was shown how they store and organise materials from past projects. I also spent time in the Library and viewed artist Corina Duyn’s reflective archive from a recent project. Seeing the work in situ; on the walls, in storage, and in use, gave me a clearer sense of how arts-and-health activity is supported within an hospital environment.

I stayed overnight in Waterford and walked on Tramore Beach that evening. I recorded a short video diary afterwards, paying attention to the sounds of the sea, the cold air, and the feelings that surfaced as I replayed the day in my mind. Later, I wrote a structured Gibbs reflection. Doing both helped me understand that stepping away from the setting (physically and mentally) is essential for clarity. That kind of time-out needs to become part of my ongoing self-care practice.

Putting the workshop, the hospital visit, the conversations, and the reflections side by side helped me confirm the direction of the bursary. This was the point where I began to feel more confident and clearer about how I want to position myself within arts-and-health practice.

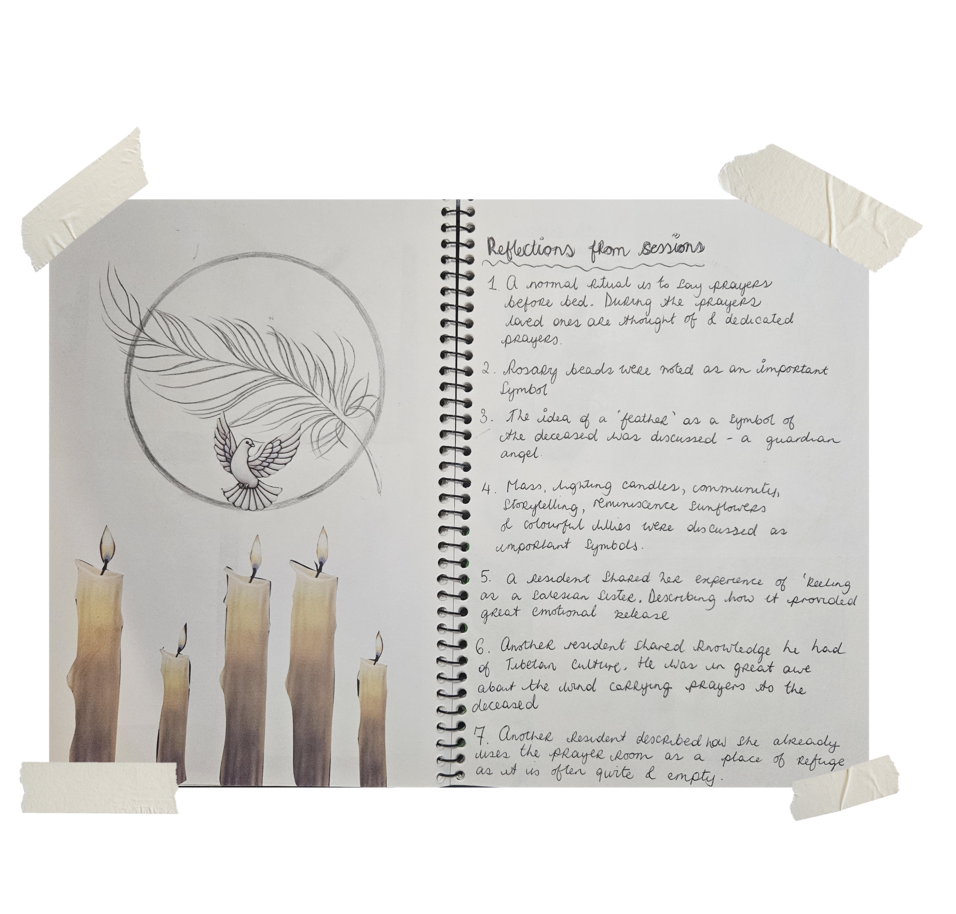

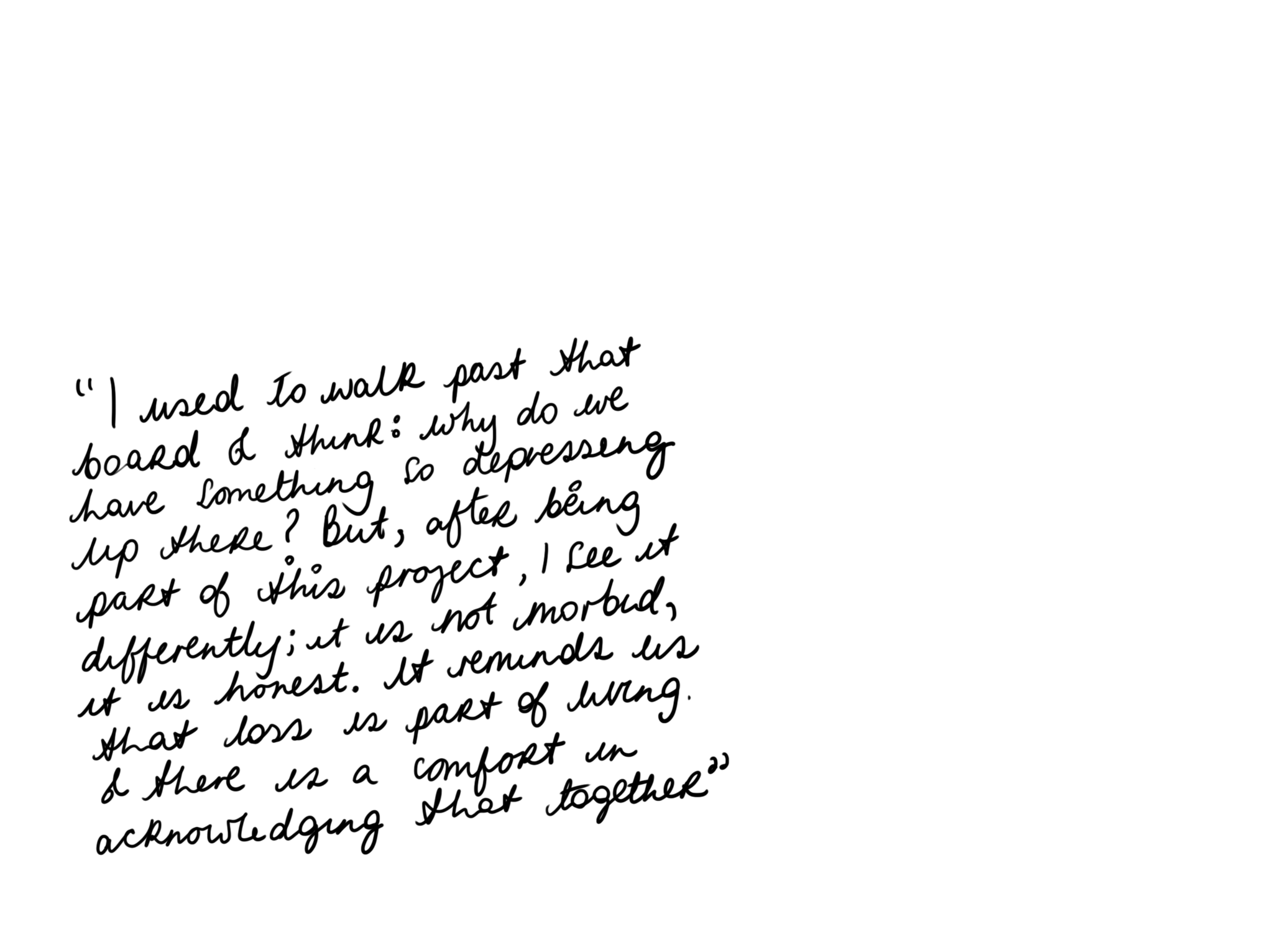

3. Seeds Grant for Arts in Residential Care Settings (2024)

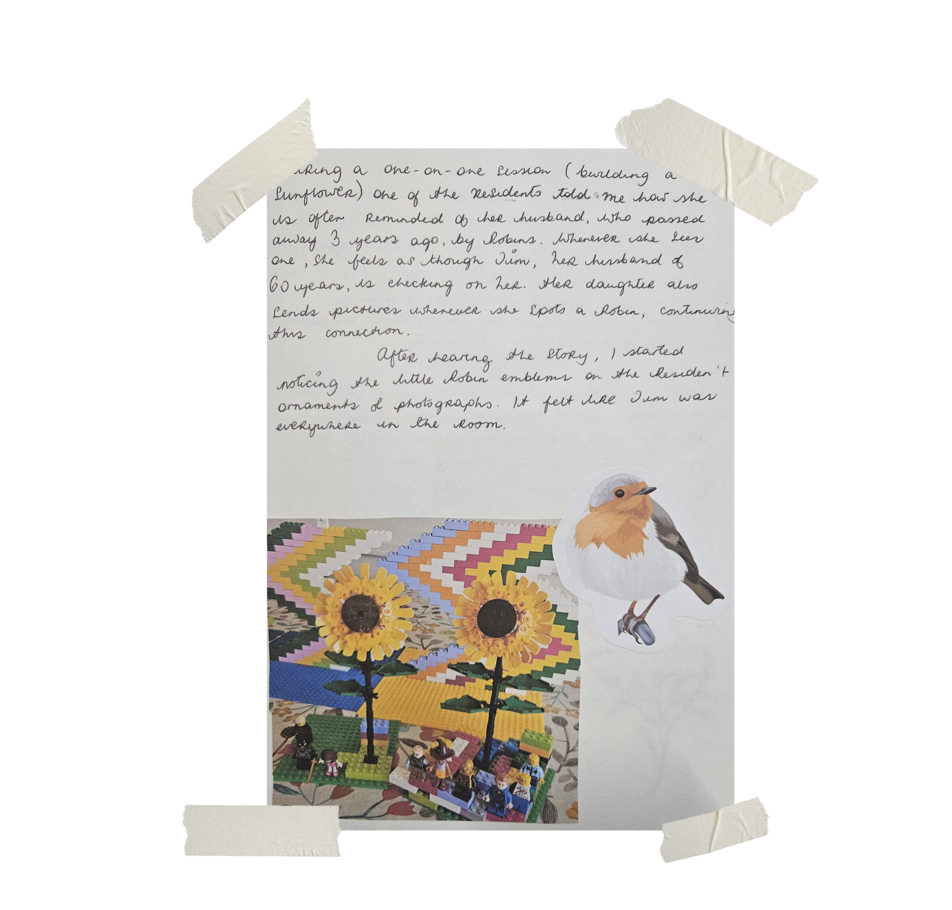

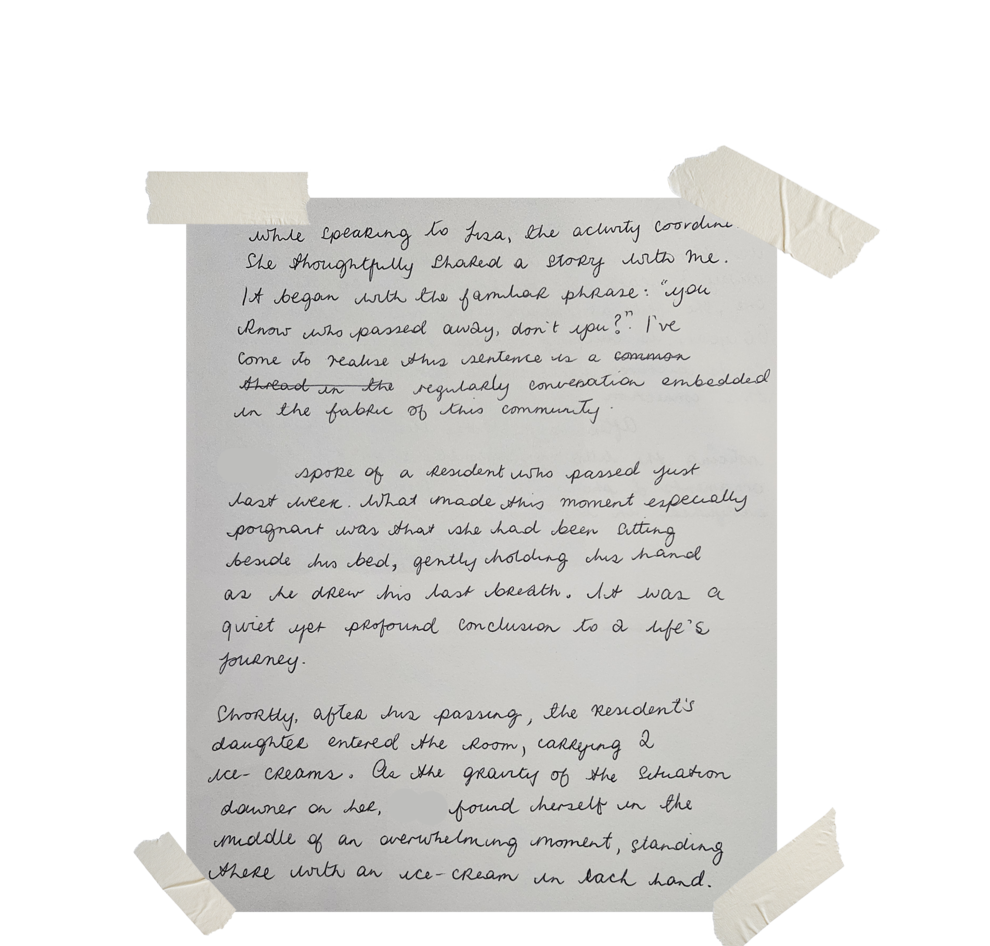

The Seeds Grant supported a project exploring themes of loss and grief within a care home through creative experimentation, funded by the Irish Hospice Foundation. I worked with residents and staff across a series of sessions using collage, storytelling, and LEGO as research methods, leading to the co-creation of a mural. It was my first project as an artist within a care environment.

During the project I kept a sketchbook. It held session notes, sketches, planning drafts, and fragments of conversation that helped me recall key moments later on. The documentation was still uneven, but it marked a definite improvement: I returned to it often, and each revisit offered new insights. At the same time, the sporadic nature of my visits reduced opportunities for on-site reflection. The lack of consistent presence made it harder to process experiences as they happened.

This project clarified the importance of scale, presence, and pacing in arts-and-health work. Creative outcomes have value, but they depend on slower relational work, continuity, and time spent in the environment beyond a single workshop slot. I also learned that structured documentation (however imperfect) supports deeper insight long after the project ends. In future, I would commit to regular full-day visits over a fixed period to allow for sustained engagement, informal interactions, and space to reflect in situ.

Revisiting this time has shown me both the value of the role and the limits I experienced within it. It clarified the realities of care work, the emotional weight carried by staff, and more knowledge on what a creative practice needs in order to effective within this environment.

Conclusion

This bursary allowed me to examine my reflective habits in a sustained way for the first time. Across the five episodes, my approach gradually shifted from fragmented notetaking to a more deliberate multimodal method. This process made the gaps in my earlier habits visible and helped me understand how important reflective approaches are within a socially engaged practice.

Building the exposition was its own learning curve. The design element was more challenging than I expected. Even with reasonable digital skills and familiarity with Photoshop, it took time to figure out how to make the different materials sit together visually and to understand the limitations of the Research Catalogue as a platform. I had to resize files, reduce loading times, adjust images so they would display properly, and develop familiarity with the platform - tasks that made me aware that this isn’t an especially accessible medium for many practitioners. The workflow was slow at the start, and at times I questioned whether I had set myself an unnecessarily technical task. But the familiarity I’ve gained is useful. I can now see how this format could become part of my ongoing practice, functioning as a digital archive for documentation and dissemination.

Moreover, the immersion in the material over the past five months revealed insights that would have been easy to overlook. For example:

- Episode 1 revealed that aspects of socially engaged practice were already emerging in my work, even if I didn’t recognise them at the time.

- Episode 2 highlighted that creative work must adapt to the demands and interruptions of the care environment.

- Episode 3 showed the value of structured documentation and the limits of over-ambitious planning.

- Episode 4 demonstrated how structured reflection can turn an emotional moment into practical learning.

- Episode 5 highlighted the importance of boundaries and the role of stepping away physically to think clearly.

Without this process, many insights would have stayed unexamined, reinforcing the 'action trap' of moving from project to project without learning from them. That pace (focused on accumulation rather than integration) can slip into burnout and dissatisfaction. It also made clear that I am still at the early stages of developing a practice within care-home environments, and shifting my focus to children at this point would be distracting and unproductive.

Working through the material in this way also helped me clarify the direction of my practice. During the bursary period, I began developing an idea for a new care home project that integrates the learning from each episode. As of the second week of November, I have been informed that this proposal has been funded by the Arts Council through the Artist in the Community Scheme, managed by Create. I will be returning to the same care home, bringing these reflections into practice, and continuing to refine the methods shaped through this bursary.

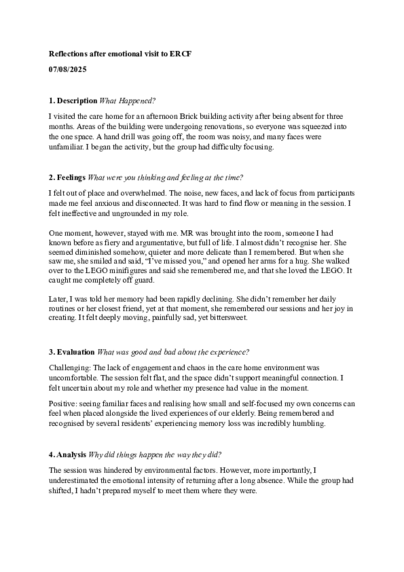

4. A Small but Significant Moment (August 2025)

I returned to the care home for a Brick-building session after three months away. Renovations had forced everyone into one noisy room, and the group struggled to focus. Many faces were new, the space felt chaotic, and I quickly felt out of place. It was a difficult session with no real rhythm.

One moment stood out, a service user I had known for quite some time, was brought into the room. I barely recognised her, she seemed quieter and more fragile than before, yet she knew me instantly. She smiled, hugged me, and remembered our LEGO sessions. I later learned her memory had declined significantly, which made the recognition even more striking. The day had a particular emotional effect on me, which was difficult to process.

However, because this visit took place during the bursary period, after the initial research, I used Gibbs’ reflective model straight away. Writing immediately helped me process the discomfort rather than ignore it, and it turned an unsettled afternoon into something I could understand and learn from.

The reflections helped me understand that the session felt difficult partly because of the environmental disruption, and partly because I hadn’t prepared for the emotional impact of returning after a long absence. The experience reinforced that not every session will 'work,' and that meaningful engagement in care settings often happens in small, fleeting moments rather than in structured outcomes. It also reminded me that shifting my practice back toward children may be premature; there is still important learning for me within care-home environments and I should continue my focus in this area.