Baroque Dance and Video Art

By Naomi Hassoun

How can historically informed video art be created using the Beauchamp-Feuillet notation system to effectively communicate the essential elements of Baroque dance and music to modern audiences and encourage embodied engagement?

Many of the stylized dances we know today have originated in music that was actually danced to on theatrical stages and at court balls, yet in contemporary concert culture, this music is most often encountered as sound alone, eliminating the connection to bodily action and spatial awareness. This research project wishes to investigate how historical dance notation from the late 17th and early 18th century, specifically the Beauchamp–Feuillet innovating system, can come to life and create an embodied experience for its audience through contemporary video art combined with live music performance. Informed by cognitive perspectives on entrainment that describe how listeners naturally align attention, timing, and movement with musical flow, the project invites audiences to experience Baroque dance music as a shared, physical, and time-based event. [1]

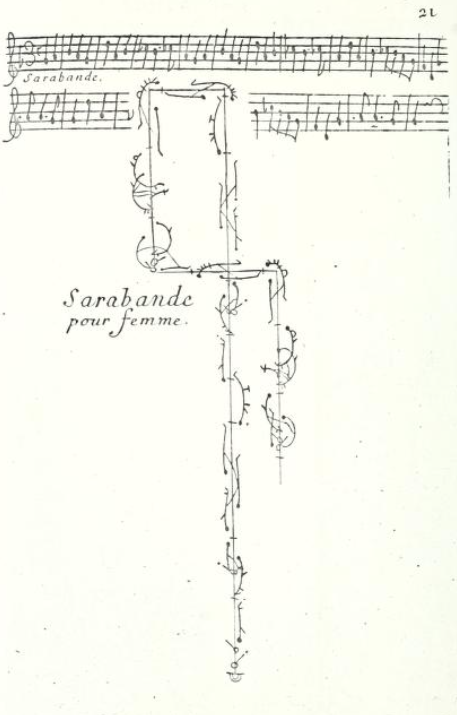

www.youtube.com/watch?v=H4DZmgdl128 Christopher Jordi Lara: Sarabande pour femme

*Last Date of Access 16/12/2025

A central focus of this research will be French dances associated with the stage works of Jean-Baptiste Lully. The dances on which this project concentrates were created for the theatre, opera, and ballet. Even after Lully died in 1687, his music became iconic and continued to represent the elevated French style, remaining widely performed throughout the eighteenth century. Already during Lully’s lifetime, many dances that were first performed on the operatic stage as part of a dramatic narrative were transformed into social ballroom dances at the court of Louis XIV in Versailles. These dances functioned as significant social events and carried strong cultural meaning beyond their theatrical origins.

As Wendy Hilton (1986) observes, “The purpose of the danse sérieuse was to provide a vehicle for the personal presence of the aristocrat, that supremely relaxed, yet alert and poised air which was cultivated from early childhood. In the ballets de cour, roles of a galante, heroic, or classical nature were assumed.” [2] This understanding highlights the close relationship between choreography, music, and embodied social identity in French Baroque dance. The movement vocabulary preserved in the Beauchamp-Feuillet notation system reflects not only rhythmic structure but also ideals of character, posture, and controlled physical expression; all of these I wish to convey in the animation work.

The initial phase of this research, therefore, aims to identify correspondences between approximately five dances preserved in Feuillet’s choreographic manuscripts and their complete musical sources. This task is complex, as many of these dances are deeply embedded within lengthy operatic works and have undergone multiple transformations as they transitioned between theatrical and social contexts. Once these correspondences are established, the research will identify the essential elements of each dance, such as dynamics, rhythm, character, and affect. These elements will then form the basis of a collaborative process with a video artist, translating choreographic and musical principles into animated visual media. Through this process, together with historical and musicological research, the project will explore how historically informed video art can communicate embodied knowledge and invite contemporary audiences to engage with Baroque dance music physically.

Bibliography

Feuillet, Raoul-Auger. Recueil de dances, composées par M. Feuillet. Paris, 1701.

Harris-Warrick, Rebecca. “Ballroom Dancing at the Court of Louis XIV.” Early Music 14, no. 1 (1986): 40–49.

Hilton, Wendy. “Dance and Music of the Court of Louis XIV.” Early Music 14, no. 1 (1986).

Little, Meredith Ellis. “Dance under Louis XIV and XV: Some Implications for the Musician.” Early Music 3, no. 4 (1975): 331–340.

Martin Clayton, Rebecca Sager, and Udo Will, “In Time with the Music,” Ethnomusicology 47, no. 1 (2003): 1–82.

Pierce, Ken. “Choreographic Structure in the Dances of Claude Balon.” Paper presented at the Society for Dance History Scholars Conference, 2001.

Pierce, Ken. “Choreographic Structure in Dances by Feuillet.” Paper presented at the Society for Dance History Scholars Conference, 2002.

Pierce, Ken. “Repeated Step-Sequences in Early Eighteenth-Century Choreographies.” 2001.

Pierce, Ken. “Uncommon Steps and Notation in the Sarabande de Mr. de Beauchamp.” Paper presented at the Society for Dance History Scholars Conference, 2003.

Pierce, Ken. “Shepherd and Shepherdess Dances on the French Stage in the Early Eighteenth Century.” Paper presented at the Society for Dance History Scholars Conference, 2005.

Pierce, Ken. “The Dances in Lully’s Persée.” Journal of Seventeenth-Century Music 10, no. 1.

Pierce, Ken. Collected Research on Baroque Dance. Accessed December 16, 2025.

Library of Congress. “An American Ballroom Companion: Dance Instruction Manuals, ca. 1490–1920.” Accessed December 16, 2025.

Ranum, Patricia M. “The 17th-Century French Sarabande.” Early Music 14, no. 1 (1986).