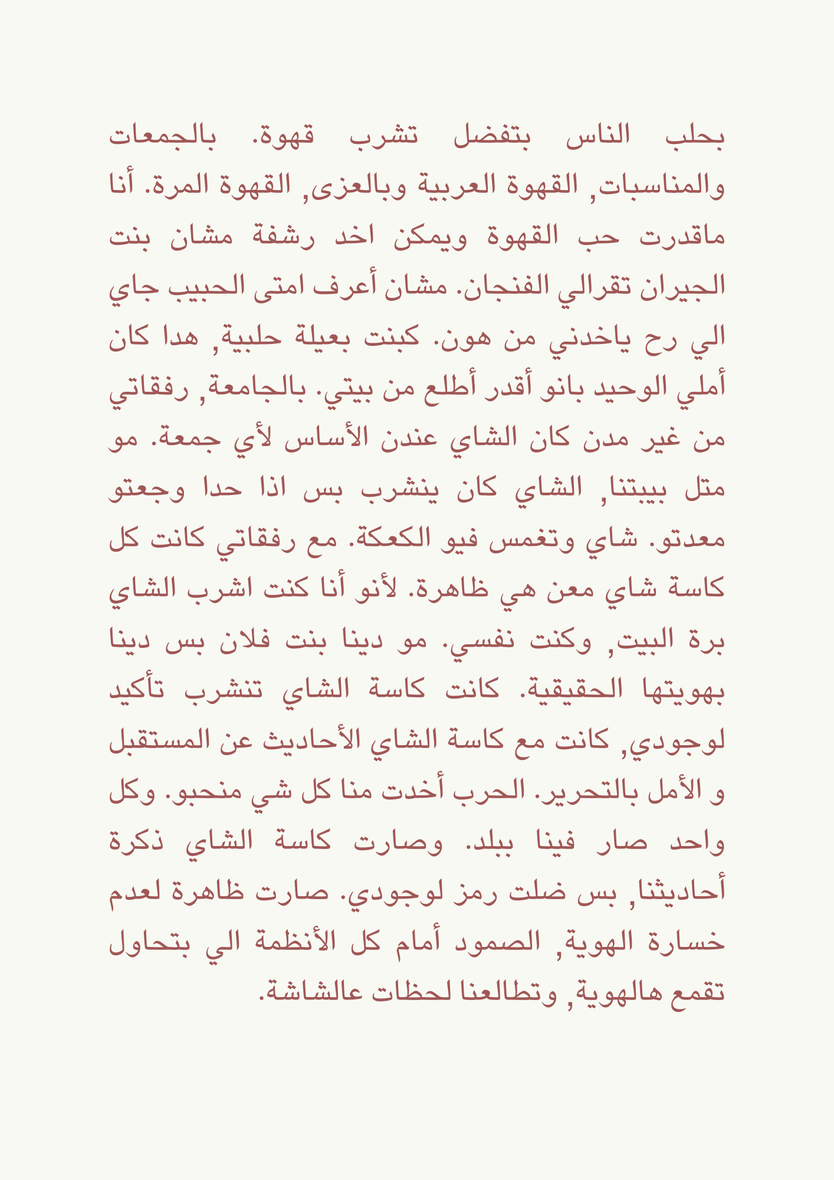

In Aleppo, people prefer coffee over tea. In gatherings and celebrations Arabic coffee, in mournings, bitter coffee. I couldn’t get myself to like coffee and maybe would take a sip so that my neighbour could read my cup. To know when love will come and take me away from here. As a bint (girl) from Aleppo that was my only hope to be able to leave home. During university, my friends from other regions, for them tea was the main of any gathering. Not like at home, we only drank it when someone’s stomach hurt and maybe we dipped a cracker in it. With my friends, every cup of tea was a phenomenon. Because I was drinking it outside of my home and I was myself. Not Dina, the daughter of someone but Dina in her true identity. Every cup of tea that was drunk was an assertion to my existence. With every cup of tea, were talks about the future and the hope of liberation. War took from us everything that we loved. And each one of us lives in a country. And the cup of tea became a memory of our talks but stayed a symbol of my existence. A phenomenon to not lose the identity and the resistance against all the systems that try to suppress this identity and show us as moments on the screen.

My project is about loving Arab men with full awareness that they can also be tyrannical, oppressive, keepers of hurtful morals and traditions, and deeply shaped by misogyny. This was my lived experience in Syria. When I left for Europe, I promised myself never to date Arab men again. It was easy to occupy the role of the victim, to speak about the Arab man, to criticize him through a discourse the West is eager to consume—a discourse that Western artistic spaces welcome when an Arab artist presents work.

“Tell us how hard your life was until you came to Europe, and how everything became good once you arrived here, with all this freedom.”

After fourteen years away from Syria, and with the beginning of my inner decolonial journey, I started noticing how acceptance and freedom in European society often come with conditions: you are welcomed when you say what is expected of you, and anything in your identity that might cause white discomfort should remain hidden, left at home. Straying from this can be dangerous—something we have witnessed clearly since October 7th, 2023. Since then, I have been watching the news and seeing Arab men who look like my father and my brother being killed, tortured, and shamed, while Western media often appears celebratory. The Arab man is not a human. When videos from Gaza attempt to portray him as a loving father, as joyful, as tender, as someone with beautiful eyes, it is done as if these qualities do not naturally belong to him.

I was forced to confront the thoughts and feelings I had collected in the West. I saw how fragmented my identity had become, how much of it was lost, and how my culture—already fragile after years of war and tragedy—had quietly withdrawn from my life. From this realization, the idea for this project emerged. As an artist, I try to understand my life through my work. The aim of this project became a return: to a lost identity, to a fragile culture, and to love for the Arab man—my life’s deepest trauma.

During the research phase of the project, I dated only Arab men. I wanted to understand why we struggle to meet each other, where healing might exist, while using love as the center to build these relationships.

I need to acknowledge that my situatedness in this project would have been different had I been living in the SWANA region. All the men I met during the research have lived in Europe for a long time and have undergone their own processes of finding fragmented identity and decolonial work. Because of this, the meetings were easy, and love was able to exist within them.

In this Master’s project, I tell these love stories while unfolding the social and political realities that shaped them. The dance emerges from reimagining my culture through my inner gaze. I am aware that my audience is mostly European, since this is where I live. Still, I create primarily for my friends’ gaze—for those who understand me without excessive explanation. English will appear alongside Arabic in the work, not to translate or clarify, but to invite the audience in while challenging them outside of their comfort zone.

Research Score:

Go out on dates with Arab me. They need to speak Arabic as their first language and were raised in their home country. Tell them about your MA research. Ask them if you can record some bits of the conversation if it comes up. There is no criteria on when to record. But preferably, while having tea and when you feel that the conversation interests you or makes you feel a certain way, record it.

Coordinates of Belonging

Coordinates of belonging is a term I stole from Lisa Nyborg when she spoke at a lecture about her “map of belonging” as a Sámi person—about land lost to the Swedish state, assimilation, and the erasure of Sámi language and culture.

And later, my MA teacher, Jennifer Lacey, gave us an assignment to create dances for Who, Where, What, When, and How, and the recipients had to like these dances. What came out were clearly points on my map of belonging. So I started using these coordinates (for who, for where, for when, for how) as a tool to create from an inner gaze.

“We live in a block universe of space-time, where nothing physically passes and vanishes, but where occasionally things withdraw due to surpassing disasters. Palestinians, Kurds, and Bosnians have to deal with not only the concerted erasure by their enemies of much of their tradition but also the additional, more insidious withdrawal of what survived the physical destruction. After the surpassing disaster, the duty of an artist is either to 'resurrect what has been withdrawn' or to 'disclose the withdrawal'."

-Jalal Toufic

When I visited Jordan and Lebanon in October, spending time in art spaces, libraries, and with artists, I noticed that I was often the only person able to hold a full conversation in Arabic. The books in these art spaces were bilingual, Arabic and English. It felt as if art could not exist in Arabic on its own, as if it needed English in order to be understood, validated, and made viable or profitable. Growing up in Syria, I attended a private school that prioritized English. Later, at university, most of our study materials were also in English. I texted my friends in English and had little interest in Arabic literature; Arabic language classes were simply something to pass for a grade. When I later immigrated to Europe, English became my main mode of communication. It was not until I began my decolonial journey in 2021 that I became aware of the near absence of Arabic in my everyday life, even when speaking with Arabic-speaking friends.

Jalal Toufic describes the catastrophes experienced by the Arabic-speaking world as “surpassing disasters,” which make tradition inaccessible in its original sense. It may still exist physically, but it no longer speaks. According to Toufic, the first task of the Arab artist is to recognize this loss. I see this loss in dance practices from the Arabic-speaking region as well. As dance has increasingly become an accessory for the tourist gaze, the culture my father grew up with is no longer practiced in everyday life. When I was growing up in Aleppo, every Friday, my father’s conservative family would take out musical instruments to play muwashahat andalusiyya and sing. My cousins and I would put on dance performances for the adults. In Syria, at funerals, one would hire dervishes to perform the sama‘ dance accompanied by musicians; at weddings, arada dancers would be invited. These traditions are now close to disappearing, alongside the growing belief that the only dance worth watching is Western dance. I see this loss, and I want to resurrect it.

For Toufic, resurrection is not nostalgia, restoration, or imitation; it is not the revival of folklore or the reclaiming of authenticity. These approaches risk producing appropriated aesthetics and counterfeit traditions that serve tourism rather than living culture. I will admit that Toufic’s language can be difficult, so I speak here from my own understanding of resurrection and how I practice it.

I work from the void. I try to create art that imagines new forms capable of carrying this loss, without aiming for something perfect or complete. I repurpose what I know, move it around, and collaborate with other artists who have felt and witnessed this loss, allowing us to reimagine together. For me, it has become increasingly important that the Arabic language is seen and/or heard in my work — to use music that comes directly from my environment, and poetry whose beauty I have learned to recognize and appreciate for the worlds it opens. And to use love as a discourse.

Glissant remarks that he claimed the right to opacity as early as 1969 at a congress at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. ‘There’s a basic injustice in the worldwide spread of the transparency and the projection of Western thought. Why must we evaluate people on the scale of the transparency of ideas proposed by the West? … As far as I’m concerned, a person has the right to be opaque. That doesn’t stop me from liking that person, it doesn’t stop me from working with him, hanging out with him, etc. A racist is someone who refuses what he doesn’t understand. I can accept what I don’t understand.’