CHAPTER 2. HIS FORTEPIANO WORKS

THE CONTEXT OF THE FORTEPIANO IN 19TH CENTURY SPAIN

During the first half of the 19th century, Spain went through strong socio-political and economic instabilities. It suffered the Independence War (1808-1814) and the political measures taken by the government of Fernando VII (1808, 1814-1833) that limited the cultural growth. In addition, Spanish society lived through two different regencies (María Cristina de Borbón, 1833-1840, and, General Espartero, 1841-43), had to adjust to the loss of part of its colonial empire, and found themselves ideologically divided. However, the social agitation and political turbulence that occurred during this time did not stop the growing interest of the amateur public to access the "fashionable" instrument in Spain as in the rest of Europe: the piano.

The Regencies of Maria Cristina (1833-1840) and General Espartero (1840-1843) were a significant period for the establishment of many musical foundations, associations, Philharmonic societies, and musical academies, i.e. societies related to art in general and specifically music. Among them were the Ateneo Científico y Literio [Scientific and Literary Ateneo, 1835], the Museo Lírico [Lyrical Museum, 1837], the Liceo Artístico y Literio [mentioned before, also 1837], the Instituto Español [Spanish Institute] and the Academia Filarmónica Matritense, also mentioned before. This situation influenced piano literature, cultivating genres associated with ballroom music such as- waltzes, dances, nocturnes, and mazurkas.- Instrumental and vocal venues were organized in palaces, private houses, other halls belonging to the Conservatory, musical societies, and publishing houses.

At the Palace, concerts were held since the 1840s. There were different kinds of venues, those were great musicians and orchestras would play, or small soirées with members of the Royal Family playing at times as soloists or accompanists. Personalities that regularly attended these venues were Juan María Guelbenzu and, of course, the teachers Francisco Valldemosa and Pedro Albéniz. On these occasions, works by Albéniz, among others, were premiered, most of them dedicated to the Queen or her sister because of special reasons (birth, death, birthday).

The Romanticism in Spain portrayed the consolidation of the pianoforte as the main instrument in life and musical creation. It belonged to every musical space, public or private: theatres, aristocratic or bourgeois halls, cafés, or any kind of soirée celebrated in houses. The piano took part in most of the contexts found in a professional musician´s life: daily practice, concert activity in all levels, or help for the composer´s labour.

The peak of the instrument was also driven by its versatility. In addition to its solo and chamber music repertoire, it has the ability to also offer reductions of orchestral and opera works. By 1820, its inevitable expansion reached all areas, and it can be said that the transition from the harpsichord to the piano was completed. Within its own evolution, the pianoforte captures the characteristics of the Industrial Revolution. The big manufactures registered innovations that increased the possibilities and gave the instrument a shape that, by the end of the century, was not very far from the final one. During this process, the range extension and the power were increased, the mechanism was considerably improved, and the sound became more equal and tuned.

From the last quarter of the 18th-century, what we find in Spain are mostly pianos imported from builders such as John Broadwood[1] or Muzio Clementi[2] in England or English copies with English mechanism (simple[3] or double[4]) made in Spain. In the Royal house, they created vacancies for piano builders[5] as an example of the support for the emerging national piano industry. During the first three decades of the century, more than fifteen workshops were established in Madrid, considered as the epicenter of this development, but there were also important builders in Barcelona, Valencia, and Sevilla. Among the most famous builders of the time, we can find Francisco Flórez,[6] Francisco Fernández, [7]Juan Hosseschrueders[8] and José Larrú.[9]

It is in the Spanish version of Clementi´s treatise, where we can find a part called “Particularities of the instruments made by Clementi&Co”.[10] From this text we can learn the several types of pianos coexisted. Firstly, the grand-piano, probably less popular but used for public concerts and mostly belonging to the Elite Society. Secondly, square pianos, whose appearance were similar to the Clavichord, and which had not only a practical use but also a decorative purpose and belonged to the High bourgeoisie. Finally, the vertical piano, which coexisted with the upright one but former remained due to basic reasons: practicality, longevity and price. In that way, the vertical piano satisfied the needs of the time.

Until the 1830s, the most common was the square piano. There were some that had English simple mechanism but most of them had the English double mechanism, considered safer, more solid, and exact in the repeating function. However, it was of course, heavier. The first pianos had five and a half octaves register but the ones that we have more documentation of are six-octaves or six-and-a-half with vertical dampers (also horizontal sometimes), two strings, and two pedals. However there are also a few exceptions on pedals: there are examples with five or six pedals, which usually are bassoon (consisting in a tube parchment on the strings), right pedal, una corda, moderator (built with a felt strip between the hammers and the strings), drum, triangle, and bells.

During the 1830s, Spanish manufactures grew and the use of the English mechanism decreased in favor of the French one[11]. Pianos became not only wider in range but also some updates were made: the hammers and the dumpers were covered with felt and not leather anymore, a double lid made with wood was included to cover the soundboard, number of pedals was standardized to two (right pedal and una corda), and also the tone was more homogeneous. With the arrival of famous pianists on tours such as Liszt, Gottschalk, and Thalberg, French pianos were imported and Queen Isabel II had, at least, an Erard and a Pleyel in the Palace[12]. During 1845 and 1850, Vicente Ferrer Aguirre and José Larrú were already building pianos imitating the French action.

[1] John Broadwood ( 1732-1812) was a British harpsichord and piano builder and founder of the oldest existing firm of piano manufacturers. After his first years as a cabinet maker, He started working for the famous harpsichord maker Burkat Shudi in 1761. After marrying Shudi´s daughter in 1769, he took over the firm from 1773 (Shudi´s death). Afterward, James Shudi Broadwood became a partner and the firm still remains in the family.

Broadwood family accomplished the most important innovations that can be found in English pianos. Among them, we can find: concreting the hammer´s striking point along the string´s length, diving the bridge into bass and treble section and taking the harpsichord´s pedal to the piano.

[2] Muzio Clementi (1752-1832) was an Italian-born British pianist, composer, and piano manufacturer. As a pianist he was worldwide, there is no doubt he was one of the best pianists of his time. He went on tour to Paris, Strasbourg, Munich, and Vienna, among others and it is very well-known his duel with Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.

As a teacher, he had remarkable pupils like Johann Baptist Cramer, Giacomo Meyerbeer andJohn Field and he wrote important pedagogical literature for the instrument: Gradus ad Parnassum, op. 44 (1817) and the Introduction to the Art of Pianoforte Playing, op. 42 (1801)

He knew how to adapt to the development of the instrument and its technique, helping to develop the language of the instrument and serving as inspiration for many others: Haydn, Beethoven, and even Mozart.

[3] The English simple mechanism was created and patented by Johannes Zumpe. It was a simplified version of Cristófori´s action, very simple and without escapement. It consisted of a rigid wire jack topped with wood and leather and fixed to the key lever. The jack impels the hammer, which is hinged by vellum to a fixed rail.

[4] The English double action consisted of an adjustable jack that is hinged to the key lever and raises an intermediate hammer, also hinged to a fixed rail. The intermediate hammer thrusts the hammer, which is hinged to another fixed rail.

[5] Both Francisco Flórez and Francisco Fernández worked for the Court.

[6] Francisco Flórez (?-1824) built pianofortes imitating the English ones. Only four of them are documented. They can be found in the Royal Palace in Madrid (one vertical and one square piano, 1807-8), Museo Municipal in Madrid (a square one) and in the Victoria & Albert Museum de Londres (a square one).

[7] Francisco Fernández (1766-1852) worked as a “pianist” in the Royal Chamber during the Kingdom of Carlos IV. Apprentices of him were Julián Lacabra or PlácidoMartínez.

[8] Juan Hosseschreuders (1779-1850)is a special case. Born in Holland, he arrived in 1802 and worked together with Francisco Fernández. Afterwards, he opened his own workshop in Madrid in 1814 and, around 1830, he will share it with his nephews Juan and Pedro Hazen. Since then the factory has gone through several stages, always by the line of direct succession, to the present. It is, therefore, the oldest company dedicated to the pianos in Spain and it is still active. Its production must have been great, since many pianos have been located with its brand. It is necessary to emphasize the important collection that has been reuniting the present owner, Felix, located in Las Rozas (Madrid).

Probably his great achievement was the “Transpose” piano or “transpose” mechanism. Pianofortes which were able to transport immediately halftone high or low through activating a knob located just in front of the keyboard. Erard had already experimented with this during the late 18th century but it was quite an innovation in Madrid. There are only square and upright pianos preserved with this mechanism.

[9] It is documented the purchase of a grand piano by José Larrú. Albéniz´s words in a letter for the Vicedirector, José Aranalde, on April 30th 1846 ”

“[…] There is no piano at school which gathers the equality of tone and pulsation and the ability of long lasting to the intensity that perfect execution of exercises and pieces requires”

After this requirement, the director asked the teacher to check himself the purchase they were about to do. Finally, the solution to the problem is found in a letter from José Aranalde, director of the school :

“The members of the Music Section from the Faculty Board, after discussing in detail the quality of the national and foreign pianos, have agreed that, in spite of being the last ones superior to the first ones, the Conservatory takes a national one to give proof of the protection of Spanish products, and due to the lack of fund to obtain a grand piano worthy of a Conservatory of Music, and meanwhile it wants to make clear what the circumstances bring along”.

[10] Types of pianos specified in the section “Particularities of the instruments made by Clementi&Co”, the Spanish version of Clementi´s treatise (6th edition, cap. III, 1811).p. 362:

- Upright pianos. Wing model standing upright.From C to F, 5 octaves and a half till 6 octaves and a half.

- Grand pianos. From 5 octaves and a half at the beginning of the 19th century till 6 octaves and a half or even 7 octaves around the 1850s.

- Square pianos. From C to F, 6 octaves and a half.

- Piano-celestino de patente real. Described as a vertical piano, long duration, perfect for all kinds of weather. It sounds like the perfect instrument for the considerable demand of the instrument existing at that time. It also says Royal patent.

It can be found in Laura Cuervo (2012, p. 9).

[11] According to documentation found at the Royal Conservatoire in Madrid, [Legajo nº 63. 12-IV-1831] they bought the first pianos for the school to Ricordi but their characteristics are unknown. The other instruments were asked to Francisco Bernareggi, who bought them in Paris. From 1845 this will become more and more common.

It seems that, under the guidance of the first director, Piermarini, importing pianos from Italy or France was not a problem. It was logical due to the more primitive state of Spanish manufacturing.

[12] Carmen Sanz Díaz. Piano Pleyel (1848-1854) y Arpa Érard, ca. 1840. Madrid; Museo del Romanticismo, sala IV, salón de baile, 2010. P. 15.

HIS WORKS WITHIN THE 19TH CENTURY MUSICAL CONTEXT

The pianoforte describes Pedro Albéniz´s musical life from beginning to end. His activity as a composer is very prolific. He wrote mostly for the piano. Excepting a few religious works, some organ music composed because of his duties as organist in San Sebastián, and the lieder op. 34, most of his works are for two or four hands. The great majority of them came up as a tool for his teaching activity at the Conservatory but, above all, at the Royal Palace. He felt that composing for students was a duty for any teacher.

He composed most of his works between 1830 and 1854, being especially fruitful during the 1840s. The reason for this is probably the appointment as the teacher of Isabel II (first princess then Queen) and her sister Mª Luisa Fernanda. In fact, most of the works are dedicated either to Isabel II or to her sister Mª Luisa Fernanda. However, the quality of these works in terms of originality or creativity is more questionable. There is a development in the style according to the previous Spanish composers in terms of writing and stylistic features, also linked to the Industrial Revolution. A difference can be observed between his first works and the latest ones (more demanding writing also related with the development of the pianos) but it cannot be said that his language belongs to a consolidated romantic style, especially not in harmonic terms (rather conservative, even quite simple). This may be because of his enormously busy life- he was, for decades, the only piano teacher at the Conservatory- due to the difficult economic and social situation in Spain, and held his post at the Royal Palace (Royal Chapel and teacher of the Royal House). Or maybe it was never his will.

In order to define his style, it is necessary to analyze what were his musical influences and the elements of his pianism in relation to his own catalog and his musical context. When taking a look into it, the first striking thing is the remarkable contrast between his piano style and that of his father, Mateo Albéniz (1755-1831). The professional admiration that the son felt towards his father is obvious and documented,[13] but there are no elements in common between their piano styles. This is probably the result of the time they lived: Mateo Albéniz´s Keyboard Sonata uses similar pianistic writing and structure to the great keyboard masters of the Spanish 18th century, Domenico Scarlatti (1685-1757) and Antonio Soler (1729-1783). In fact, although we know the existence of pianos bought to Florencia at Maria de Braganza´s Court[14], we have no certainty if the sonata was meant to be played in the harpsichord, the fortepiano, or even both.

After his first years as an organist, Pedro´s experience in Paris was clearly a turning point in his creative search. He built his own language as he wrote his method, researching and taking what he observed from his surroundings. His contribution to the European musical society outside Spain is probably not remarkable. He assimilated the tendencies and piano writing from the biggest names of 19th-century Paris but he did not develop a very personal style. However, his contribution within the Spanish context it is transcendental both because of its quantity and innovation.

His pianism evolves from the contradanzas (first piano work known) to the big fantasies for two hands, and derives from, (in order of increasing importance), Spanish folklore, Italian opera, and the pianistic writing and resources used in 19th-century Paris, and is influenced by two capital figures: Friedrich Kalkbrenner (1785-1849) and Henri Herz (1803-1888).

His music has two main recipients: his students and the amateur public. Probably, his pedagogical labor occupied most of his time and that is precisely one of the reasons why several of his works seem to be for educational context, both within the Conservatory and later in the Palace.

When one observes his catalog, it is clear that most of his compositions are two or four-handed works of medium difficulty, written to be performed mostly by amateur students. In fact, he wrote in a considerable variety of genres: caprice, variation, waltz, rondino (solo, four-handed, with quartet or quintet), nocturne, and, above all, fantasies for two and four hands. He cultivated most of the genres in fashion at the moment, from ballroom music (gallop, nocturne, waltz) to the most demanded fantasies and variations (especially popular the ones based on opera arias). He translated all his learning in Paris to the Spanish reality, developing genres seldom used until those years –such as the variations or the fantasies- and updating the “older” ones with his own language, influenced by personalities such as Henri Herz and Friedrick Kalkbrenner.

No doubt that the variations, rondos, and fantasies on opera or popular themes were his most famous pieces. They were essentially pieces with a favorable market release. It served the taste of the aristocratic and bourgeoisie circles close to him, especially from 1841, when he was appointed a teacher of the Royal House.

From the waltzes and nocturnes to the repertoire for four hands, they are works that, written within the archetypes of each of the genres, meet the requirements of pedagogical repertoire: they work certain pianistic elements, adapt to the level of the student and are easy to listen to. Examples of this kind of repertoire are: some of the waltzes, the nocturne “La Isla de la Cascada de Aranjuez”, the Danzas características españolas for four hands, the fantasies for four hands, the melodic studies, and some short pieces gathered in his method (like the Fantasía sobre motivos from La Violeta). As proof of this pedagogical trait, most of his four-handed pieces present the secondo part as the most difficult, and it is, in fact, documented,[15] that this part was played by him.

On the other hand, there are a considerable number of works that require a mastery of the most demanding and refined mechanism. They are works that seem to be written for pianists in a more advanced stage of their training or for professional pianists. Examples of this repertoire are the fantasies and variations for two hands and the Rondó Brillante a la Tirana sobre los temas del Trípili y la Cachucha, op. 22.

[13] It can be found in Chapter 1 of this research, P. 11.

[14] Cristina Fernandes. "María Bárbara de Braganza y la cultura popular europea del siglo XVIII". Dossier"Música en corte femenino". Coord. Judith Ortega. Revista Scherzo. Madrid, Instituto Complutense de Ciencias Musicales. P. 77.

[15] Gemma Salas Villar. “Pedro Pérez de Albéniz, pianista y maestro de la Reina Isabel II”. The lecture can be found in: Gómez Rodríguez, José Antonio, ed. El piano en España entre 1830 y 1920. Congreso celebrado en Museo del Traje, de Madrid, del 7 al 9 de mayo de 2009. Madrid: SEDEM, 2015.

WORKS INSPIRED BY SPANISH FOLKLORE

It seems plausible that Pedro Albéniz's first contact with Spanish folklore in piano music was through the keyboard authors of the 18th century mentioned before (including, of course, his father), who used elements of the Spanish-American folklore for the elaboration of their sonatas.

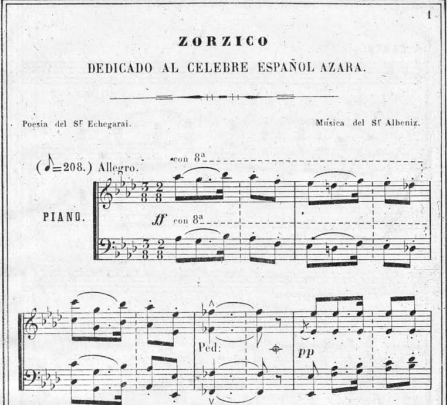

Part of Pedro Albéniz´s artistic activity also finds its inspiration in the Spanish folklore, especially appreciable in his Danzas características españolas and the Rondó Brillante a la Tirana sobre los temas del Trípili y la Cachucha, op. 22. Some of the elements he takes from the popular Spanish culture were used before but they are treated in a completely different way. Examples of this are the seguidilla or the fandango, already employed by the Escuela bolera[16] from the 18th century. Other elements that he uses have no background in Spanish piano literature. An example is, the use of zortzico, belonging to the Basque folklore, which Albéniz felt very close to after living thirty-five years in the Basque Country. It was precisely his connection with this region that impelled him to elaborate, together with Juan Inzenga, a popular Basque songbook.

Pedro Albéniz´s Contradanzas bailadas[17] were his first documented fortepiano work. They were written, among other compositions, for the Royal reception in San Sebastián (1833). Pedro Albéniz was in charge of the musical events for the occasion. The Contradanza, also called contradanza criolla, danza, danza criolla, or, later, habanera, is the Spanish and Spanish-American version of the French contredanse, a very popular dance during the 18th century and adopted at the French court. It was usually performed by an orchestra of two violins, two clarinets, a contrabass, a cornet, a trombone, an ophicleide, a paila, and a guiro. It is thought that this Cuban influence arrived in Spain through the sailors, becoming especially linked to the habanera and being the source of inspiration for a wide amount of composers.

In the case of Albéniz´s Contradanzas bailadas, they were clearly thought to be danced, as he specified in the title, and probably also accompanied by instrumentation. The structure and character of theContradanzais present in his pieces, as well as its harmonical simplicity, and its tendency to be ornamented.

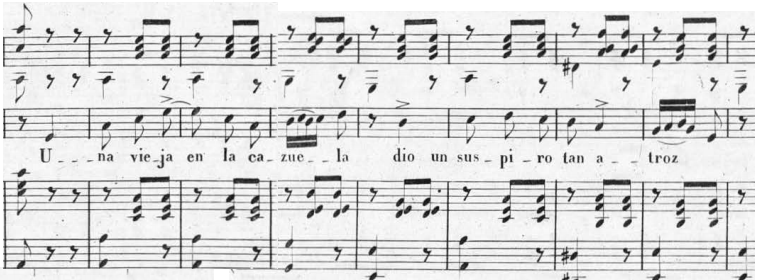

The best source of 19th-century Spanish folklore used in the piano literature is the Corona musical de canciones españolas (1852). [18] Renowned artists of the Spanish society participated in this project dedicated to J. N. Azara[19]: Mariano Soriano Fuertes (1817-1880), Manuel Lafuente, Nicolás Toledo (d.¿-1881), Camilo Mojón yLloves, José Sobejano (1791-1857), José Inzenga (1828-1891), Florencio Lahoz (1815-1868), FranciscoFronterodeValldemosa (1807-1891), Rogelia León (1828-1870), Ramón Sans y Rives (d.¿-1870), Joaquín María Bover (1810-1865), and José Echegaray (1832-1916).

Within this work, popular songs from different Spanish regions can be found: muñeira (from Galicia),canciones asturianas and andaluzas (from Asturias and Andalucía),seguidilla (from Castilla), Jota from (Aragón and Valencia),canciones catalanas (from Cataluña) y mallorquina (from Mallorca) or Zorzico (from País Vasco).

Danzas características españolas

The collection of Danzas características españolas gathers four-handed pieces based on rhythm or motifs coming from folklore. Part of this set, are El chiste de Málaga, op. 37 [The joke of Málaga], La gracia de Córdoba, op. 38 [The Grace of Cordoba], La barquilla gaditana, op. 41 [The gaditian boat], La sal de Sevilla, op. 40 [The Salt of Seville] and El polo Nuevo, op. 41 [The new polo]. In these works, the author uses material from popular Spanish music: polos, fandangos, and seguidillas among others. The result is simple pieces which are not an attempt to be concert pieces but classroom ones. They are thought of an introduction to the elements of Spanish folklore. Some of them are built according to a rhythmical pattern identified with a specific dance, and other ones simply use melodic twists or harmonic relations which are clearly inspired in popular music. They are a reflection of the importance that the education already had to the elements belonging to Spanish music and culture at that time. The 1830s were precisely the origin of the nationalist ideology as part of the romantic spirit, and a lot of composers began to compose works of all kinds with inspiration in different elements of popular folklore and national culture.

The Seguidilla, diminutive of seguida, which can be translated as "sequence", is the name of an old Castilian folksong and accompanied dance form in quick triple time. It was meant to be for two dancers accompanied by castanets, guitars, bandurrias, and lutes. It has several regional variations, but we can say it is generally in a major key and often begins with an upbeat. It is commonly thought that the earliest and most influential of the types of seguidilla originated in either La Mancha or Andalucía, having become part of the folklore of central Spain. Different versions include the seguidilla manchega (from Castilla-La Mancha), the murciana (from Murcia) and the slightly faster sevillana (from Sevilla). However, the high point of this dance and most complex of its variants will be the seguidilla flamenca, or seguiriya, which is used in flamenco music.

It can be found in different meters – 3/4, 3/8, 9/8- but always triple meter. The best example can be found in the Corona musical de canciones españolas, at the right side of the text.

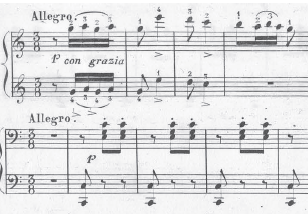

An example of Seguidilla within Albéniz´s works can be found in La Gracia de Córdoba, op. 38. After a four-bar introduction, the secondo part starts playing an ostinato with that characteristic rhythm.

The fandango is a lively dance and song in triple time, popular in Spain and Latin-America and traditionally accompanied by guitars, castanets, or hand-clapping. It can be found mostly in 3/4 but also in 6/8 and 3/8 and it has a distinctive harmonic pattern: A minor, G major, F major, and E major.

At the end of the 18th-century, it became fashionable among the aristocracy and was often included in tonadillas, zarzuelas, ballets, and operas, not only in Spain but also elsewhere in Europe. In keyboard music, several examples can be found: D. Scarlatti, Keyboard Sonata K. 492 (1756), A. Soler, Fandango for harpsichord, F. Lahoz, El fandango y la jota (from Pot-pourrí de aires naciones con nuevos cantos y variaciones, op. 35), E. Granados, Fandango en el candil and Serenata del espectro (from Goyescas, 1912-14), I. Albéniz, Málaga (from Iberia, 1905-08).

The polo is a palo (or traditional form) belonging to Flamenco music and dance which most usual rhythm structure is 3-3-2-2-2 but it can also be 3-2, as we see in Pedro Albéniz´s example. It is always accompanied by guitar and the melodies are built in Phrygian mode.

His Polo Nuevo is again part of the Danzas características españolas and it is also the secondo part the one that gives us the clue to the kind of dance we are listening to. However, it does not contain the Phrygian mode characteristic of this music, so the inspiration is just rhythmical in this case.

Albéniz and the Basque folklore

The first collection on Basque melodies, Anciñaco Euscaldun Ancina (Canciones antiguas vascas) was published in San Sebastián in 1826, under the guidance of Juan Ignacio Iztueta[20] and Pedro Albéniz, and it posed considerable importance for the recognition of Basque music. The collection had an ambitious purpose according to the authors:

“This collection is not considered like recreational work, but as a true national monument” [21]

It is basically a compendium of popular Basque melodies which served to the development of the Basque folklore during the following decades.

The Zorzico or Zortziko inspired a lot of composers, especially from the end of the 19th century. The zorzico is a traditional song and dance originated in the Basque Country, Navarra and the south of France. Although it can be in 2/4 and 6/8 its most common version is 5/8 consisting of two subdivisions of 3 and 2 or three subdivisions of 1, 2, and 2 beats (1+2+2).Within the piano literature, Isaac Albéniz, wrote a Zorzico in his suite for piano España, op. 165 as did Charles Valentin Alkan and Maurice Ravel, who included a Zorzico in his piano trio. However, the emerging knowledge about Spanish popular music mentioned before goes hand in hand with that of each region of Spain. In this case, the first zorzicos, the most famous and employed dances and rhythms from Basque folklore, began to come out already in the middle of the century (the publication of the Corona musical de Canciones Españolas and the Anciñaco Euscaldun Ancina).

Rondó brillante a la Tirana sobre los temas del trípoli y la cachucha, op. 25

Published around 1825 in Madrid, is one of Albéniz´s most brilliant and accomplished pieces, certainly his biggest one with inspiration in Spanish folklore.

It is structured with an introduction, the Rondó, and the coda. Within the Rondó he exposes two thematic materials that have a clear origin from the title: La Tirana and La Cachucha. The Tirana was a popular music genre during the 18th century which was the source of inspiration for several composers during the 19th century in Spain. It was both danced and sung, and it was very often a substitute for the seguidillas at the end of the tonadillas[22]. It was written in a fast and syncopated 3/8. The most popular appeared in the tonadillas by Blas de Laserna and Pablo Esteve and it was recovered by Ramón Carnicer in his tonadilla Los maestros de la Raboso o El Trípili (1836): La Tirana del Trípili or El trípili, trápala.

The second thematic element present in the Rondó is the Cachucha. It was known by this name as a Spanish solo dance usually written in 3/8 rhythm and accompanied by castanets. It is considered the Andalusian version of the Bolero. Already in the19th-century it was, one of the most appreciated Andalusian dance in Europe, together with el Jaleo de Jerez.

[16]The Escuela Bolera is an artistic, dance and scenic expression unique and complex. It is a variation of the Spanish dance and has a considerable influence on classic dance. Its origin is the court French and Italian dance from the XVII. Already in the 18th century is considered as one of the basic Spanish popular dances but it will be during the 19th century when it will be assimilated as the national dance. It will be the dance representation of the musical nationalism in Spain.

[17] Most of his works can be found online through the Spanish National Library in:

[18] The Coronamusicaldecanciones españolas can be also found online through the Spanish National Library:

[19] José Nicolás de Azara (1730-1804) was a procurator-general, active diplomatist and ambassador at Rome. He took a leading role on expulsing the Jesuits from Spain and the election of Pope Pius VI. As his representative, he took the responsibility of the negotiations with France for the Armistice of Bologna (1796). Years later he was Spanish ambassador in Paris, being forced to negotiate the Treaty of San Ildefonso, by which Spain agreed in principle to exchange Louisiana for Tuscany but where, in reality, Spain ended submitted to Napoleon´s will.

[20] Juan Ignacio de Iztueta Echeberria (1767 - 1845) was a Spanish writer, historian, and folklore specialist. He was a pioneer in the compilation of Basque folklore. His work Guipuzcoa´ko dantza gogoangarrien kondaira edo [Memories of the history of Guipuzcoan dances] was edited in 1824 and supposed an absolute reference in his field.

[21] Denis Laborde. International bibliography of musical science. DNB, 2005. P. 38. This collection can be found online through the Spanish National Library:

[22] Tonadilla escénica was a type of Spanish song which originally comes from the theatre. It usually has a satirical and comical character and it is absolutely based on the popular in 18th and 19th century Spain. It will also develop later in Cuba and other Spanish colonial countries. The tonadilla surely influenced the growth of the zarzuela, which still is the characteristic Spanish form of musical drama or comedy. Remarkable composers of tonadillas in Spain were Blas de Laserna, Pablo Esteve, Enrique Granados or Joaquín Rodrigo.

Contradanzas bailadas by Pedro Albéniz. Performer: Julián Turiel. June 2018.

Part of the 1st-year recital program. AS Zaal, Koninklijk Conservatorium Den Haag.

Keyboard Sonata in D major by Mateo Albéniz. Performer: Julián Turiel. June 2018. Part of the 1st-year recital program. AS Zaal, Koninklijk Conservatorium Den Haag.

BALLROOM MUSIC

A new listener appears in the musical scene: the bourgeois. The musical interest of this social stratum is reflected in ballroom music: easy and refined music to listen to. As amateur musicians, they liked the music to play at home. New musical spaces appear as a result of the increasing artistic demand: halls, academies, philharmonic societies, concerts. Examples of this will be the Ateneo and the Liceo. The Ateneo (Madrid, 1835) was a place for cultural and musical presentations and discussions while The Liceo Artístico y Literario (1840) was an institution where literature received a great impulse, traditionally more than music. There were public lectures, lessons, art presentations (especially painters and sculptors) and musical celebrations and concerts. Figures as Liszt, Thalberg or Gottschalk performed there.

The ballroom music was the most performed in these institutions. During the 30s, the waltz [also written as vals or wals] and the rigodones, were the predominant genres ahead of the mazurka and the gallop, based in opera and dance. The perfect combination between both fashions is the waltzes and rigodones´ sets based on the opera themes. In addition, piano arrangements for dances played by orchestras in theaters and halls are very common. The hits of the carnival season are published each year in collections entitled Carnival Nights, Carnival Evenings or Carnival Day.

The Center-European dances such as waltzes, polonaises, mazurkas, gallops are present in halls all over the capital after Spanish opening to foreign influences. This is also reflected in critics, press and musical edition.

Waltz

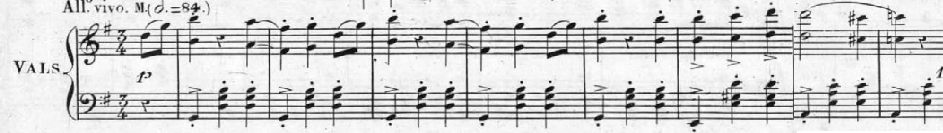

The waltz is the most cultivated dance by Albéniz. According to their quality, three of them stand out, called: El clásico [The classical], El romántico [the romantic] and the Anfión Matritense[23], all of them typical concert waltzes. They were also, together with the Huit waltzes pour le piano-forte, the only ones published. The rest of them, around fifteen more, are layed up in one of the Queen´s music albums.[24]

All the waltzes have a structure in several sections (In the case of some of the concert waltzes, preceded by an introduction and followed by a coda). The rest of them have a more simplified ABA structure plus coda where each section modulates to close tones. The concert waltzes do have a virtuosic intention more visible in the codas although without reaching the level of the variations and fantasies for two hands. They present writing which takes advantage of the whole extension of the keyboard and employs the singing in octaves as a tool to vary a theme or motif. This results in writing full of jumps and brief and long octaves passages in considerably fast tempos. On the other hand, the lower register also presents its difficulties. The left hand is usually written in two in two differentiated registers (bass and chord), creating again jump, although within a quite simple harmonic language. Thus, the writing of these waltzes is mostly one of the extremes, where the singing in octaves in the high register and the powerful and deep basses make the middle register perhaps a bit empty and the sonority suffers.

The waltzes present a regular symmetrical Romantic structure. The theme is repeated in octaves or ornamented (especially with appoggiaturas). There is no transformation of the material but variation or contrast of themes, which do not develop. The pedalization simply denotes emphasis in the first part of the bar, either in the cadences and, above all, feels necessary in the higher registers as he also recommends in the method[25].

Nocturne

The intimate genres (nocturnes, ballades, romances without words, melodies, meditations, pensée poetique, lieder, confidence) were part of the 19th-century ballroom repertoire. Composers representative of these genres were Alkan (1813-1888), Field (1782-1837), Hummel (1778-1837), Cramer (1771-1858) or Chopin (1810-1849) in Europe and Santiago de Masarnau (1805-1882) [26]or Marcial del Adalid (1826-1881)[27] in Spain.

This trend appears in Spain as a reaction to the virtuosism (which we can certainly frame Pedro Albéniz but also his references: Herz and Kalkbrenner), something that already happened in Europe with personalities such as Schlesinger, Brandus or Schumann, who defends the work of Chopin, Alkan or Heller (1813-1888) against Herz, Hünten (1792-1878) or Doehler (1814-1856). This repertoire was performed in Private halls, belonging to bourgeois and nobility. In Spain, it was again Masarnau who promoted them. Every Sunday, the most important figure of the Madrilenian cultural society gathered together. Other personalities such as Mendizábal or Guelbenzu organized this with pedagogical purposes, presenting European repertoire that was often not very common in other halls.

It is precisely in the critics on two pieces by Pedro Albéniz, the Variaciones brillantes para pianoforte sobre la Introducción de la Norma de Bellini, op. 27 and the Variaciones brillantes sobre el himno de Riego, op. 28 when Santiago Masarnau offer us his opinion on Albéniz´s style (identified with Herz´s) in contrast with the one he likes, the intimate one:

"We have always said with honesty, and we repeat now, that Herz's style is not the one we like the most; but our self-esteem is not as big as to pretend our opinion to be the only right one. We respect Herz’s works and we also highly appreciate him but we cannot help preferring the expressive and sentimental genre of the Hummel and Cramer because it suits our organization or way of listening, which we cannot vary”[28]

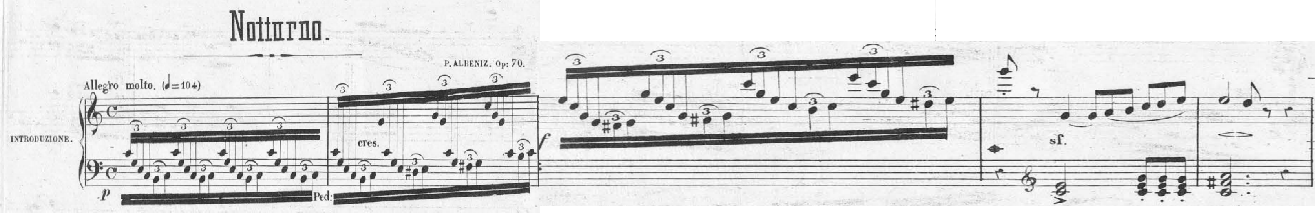

These genres are the absolute minority in Albéniz´s catalog, as well as in Kalkbrenner and Herz´s. He composed a romance for two pianos, two lieder, and two nocturnes as far as we know. They are works structured in three parts with introduction and coda.

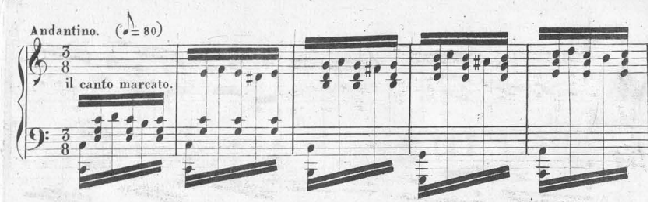

Pedro Albéniz considers the nocturne a useful and pleasant genre[29]. He wrote two nocturnes, Mi delicia op. 61 for four hands and La isla de la Cascada de Aranjuez, op. 70 for two hands. The basic pianistic designs are nothing different from the rest of his repertoire. However, in the nocturne titled La isla de la Cascada de Aranjuez [The island of Aranjuez´s Waterfall], we find quite a special writing as a recurrent element in the piece. The figuration, which is in every section a rhythmical Perpetuum mobile, is shared between both hands throughout the composition, a feature that makes us reflect on the possible pedagogical nature of this composition. The indication pedal matches with the ideas he writes down in his method and is quite concrete. For example, in the second part, he specifies its use only for the first part of the bar, something that denotes, as well as happened in the waltzes, the willing of lightness at the end of the bar.

[23] Name of a Spanish musical newspaper.

[24] It can be found in:

Emilio Casares and Gemma Salas."Pérez de Albéniz, Pedro". Diccionario de la Música Española e Hispanoamericana, vol. 8. Madrid, SGAE e INAEM, 1999.P. 636.

[25] It can be consulted in the first chapter of this research. P. 30.

[26] Santiago de Masarnau (1805-1882)was the contemporary of Pedro Albéniz, he comes from the heart of a wealthy family. He studied in Madrid with José Rouré y Llamas, José Boxeras, José Nono and Ángel Inzenga. Due to his father´s post, he spent his childhood close to the environment of the Royal Palace. He continued his musical learning with Schlessinger in London and Paris, he became very close to José Melchor Gomis and was very influenced by Alkan and Chopin´s personal style.

When he came back, he started teaching at a secondary college. He translated Hummel´s method for piano and published it together with a new solfége method and two essays on his thoughts about piano, interpretation, and teaching: La Llave de la ejecución [The key of execution]and El Tesoro del pianista [The pianist´s treasure]. Furthermore, he was a great concert organizer and a very active music critic for El Artista.

His style, influenced by ballroom music, is clearly romantic. The greater part of his catalog is dedicated to piano, although he also explored chamber music, symphony and vocal music. Many of his creations were published in France and England and subsequently re-edited in Spain.

[27] Marcial del Adalid (1826-1881) was a Spanish composer and pianist. He studied music in London between 1840 and 1844 with Ignaz Moscheles and some sources also mentioned he could have studied with Chopin in Paris. Both men influenced the style and form of his musical compositions. After finishing his studies, he returned to A Coruña and later Madrid. Highly influenced by lieder, his most important compositions were vocal art songs and songs for the piano. A particularly fine example of his work is his 1877 composition Cantares nuevos y viejos de Galicia where he successfully blended the folklore of Galicia with the technique and spirit of Romantic piano music.

[28] Gemma Salas Villar. “Santiago de Masarnau y la implantación del piano romántico en España”. Cuadernos de Música Iberoamericana, nº 4. P. 197-222. ISSN 1136-5536. Madrid, 1997. P. 15.

[29] Cover of the nocturne “La Isla de la Cascada de Aranjuez” [the Island of Aranjuez´s Waterfall]

El anfión matritense. Waltz in G major. Performer: Julián Turiel. June 2018, AS Zaal, Koninklijk Conservatorium Den Haag.

WORKS INSPIRED IN ITALIAN OPERA

If we take a look into Albeniz´s catalogue for pianoforte we can mostly observe a considerably large amount of works which have the inspiration in Italian opera. The answer to this can be found in the announcement of La Rosibella [or “the great Italian symphony taken from the most pleasing pieces of operas composed by Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti and others of such well-known merit"], published by Hermoso and Lodre in 1834:

La mayor parte de las piezas de una ópera tienen varios pasajes favoritos y de gusto general. El placer que puede recibir el oído al escuchar una pieza compuesta de dichos pasajes enlazados con arte, lo deja a la consideración de los aficionados, pues sin disputa es lo más grato que puede tocarse en el piano, y por consiguiente de más fácil ejecución, que puede verificar cualquiera señorita aunque no tenga mucha práctica, y lucirse extraordinariamente con poco trabajo, pues su mismo gusto estimula al estudio y la fija con mucha facilidad en la memoria. Los tres primeros números serán sacados de las mejores sinfonías, e irán combinados de tal modo, que si se quiere se tocarán dos, tres o más números o cuadernos juntos, y parecerá una sola pieza.

Most of the operas have several favorite passages that are also the audience preference. The aural pleasure while listening to a piece composed by those passages artistically linked, is left to the consideration of the fans, because it is, without a doubt, the most pleasant thing that can be played on the piano, and therefore of easier execution. Any lady can extraordinarily verify with little work because its very taste stimulates the study and fixes it very easily in the memory. There will be taken the first three numbers from the best symphonies and will be combined in such a way that, no matter if you play two, three or more numbers or books, it will look like one piece. [30]

The Italian opera is described as general taste, the most pleasant and the easiest to play. This kind of music was not only heard in theatres but also in most of the music circles. There is no doubt that the pianoforte was the preferred instrument to take all these favorite passages from the operas and made them possible to play for amateur musicians. Apparently, they were conceived as the fastest pieces to be learned because they were colorful and familiar to the ear of the student.

In fact, according to XX most of the operas had their own piano arrangement:

"One could easily track the opera premieres and their success simply by counting the fortepiano arrangements that are published each year. Although today we may be surprised by this practice, in the 19th century any successful operatic premiere was followed by the piano arrangement of its most important numbers or even the entire opera, including overture".[31]

Thus, the opera was also trendy within the pianoforte context of the time. From the beginning of the 19th-century collections of opera, arrangements are edited. Example of this are the set of pieces described in El Eco de la ópera italiana (1833), which gathers the most famous opera pieces from Il Pirata, Esule di Roma, Anna Bolena, Monteschi, Fausta, Sonnámbula, Straniera, Donna del Lago, Otelo, Moïses, etc. arranged for pianoforte.

In addition, fantasies, rondos, pollacas, capriccios and variations on opera themes or motifs were not only made for the taste of the amateur public but for synthesizing the content of an opera. So, it cannot be ensured that the purpose of this repertoire was further than arrangements, reductions of the most popular parts of these operas, performed as a kind of service to the amateur pianist lover of music, and, therefore, of the Italian opera. In 1830 operas of Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti, Meyerbeer, Pacini, Ricci, etc., were fashionable and at least two by Spanish authors: Elena and Malvina by Carnicer and Ipermestra by Saldoni.

Among the foreign composers who developed this kind of repertoire can be found: Herz, Czerny, Hünten, Duvernoy or Thalberg. We can also find names in Spain apart from Pedro Albéniz, for example, Basilio Basili, the Ronzi brothers, Alejandro Esain, Romano Hurtado de Mendoza, José Sobejano, Santiago Medeck or Joaquín Espín y Guillén.

VARIATIONS

During this time, variations and fantasies are closely related in many aspects. First of all, both genres had the same sources of inspiration: folklore and opera. Furthermore, both give the composer the context to develop a virtuosic and rich language.

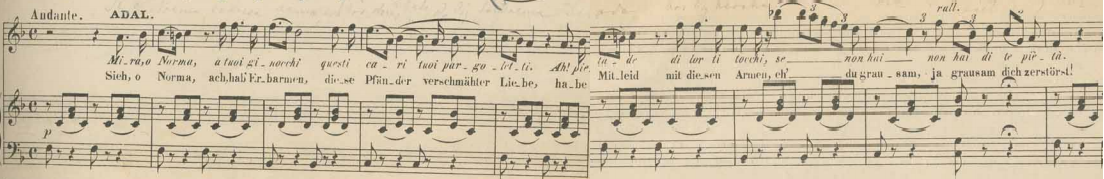

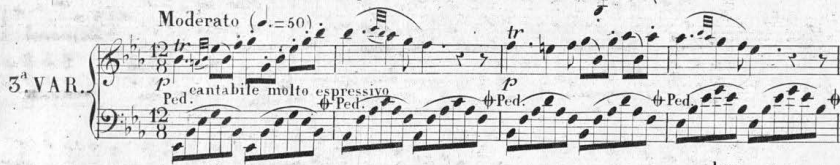

As his chronology shows us, the variations were written before the fantasies. This fact, together with his consideration on composing fantasies, explains the influences that the variation genre has on the fantasies, being often a common compositional method. Variations analyzed for this research were: The Variaciones brillantes sobre el Himno de Riego, op. 28, The Variaciones brillantes para fortepiano sobre la Introducción and the Variaciones brillantes sobre el aria favorite “Mira, Oh Norma, ai tuoi ginocchi” de la Norma de Bellini, op. 27 and 33 and The Variaciones para piano sobre un coro from Il Crocciato in Egitto de Meyerbeer. Other variations written by P. Albéniz whose score could not be found during the research process were: the Variaciones para piano sobre "Tu vedrai la sventurata" from Il Pirata by Bellini, and, the Variaciones brillantes para piano y cuarteto de cuerda sobre “El ultimo pensamiento” by Bellini, op. 8.

The form and thematic content of the variations are relatively simple. After analyzing all the variations we were able to get, the most recurrent structure is the following:

Introduction+ theme + three variations - very elaborate final (Coda + Finale)

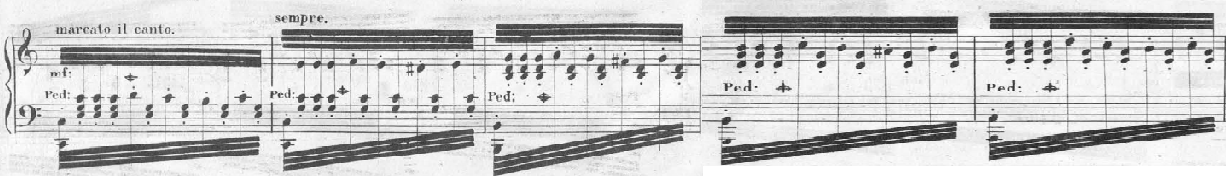

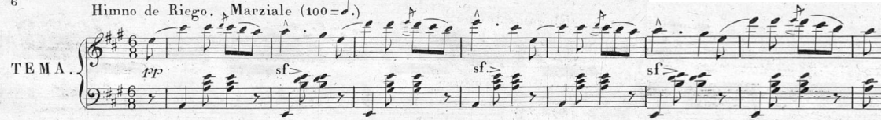

The Introductions are usually written in the same tonality as the theme as a way of setting the mood of the piece. They are often quite big in terms of writing, probably conceived as a short overture or prelude. They are inspired in orchestral textures: tremolos imitating drumrolls, big wide arpeggios as performed by a harp, octaves, and chords on dotted rhythms, very typical of brass band instruments. His dimension is also a resemblance to the kind of work that is presented. For example, the Variaciones sobre el himno de Riego are his biggest set and we can observe that from the introduction. It constantly changes the character and the texture, the writing is very virtuosic from the beginning (large passages of scales, arpeggios, repeated notes, octaves) and the specification in the character indications is nothing compared to the rest of the Variations set. (The examples can be visualized in the right side)

However, Albéniz´s use of the material is sometimes completely different. An example is the introduction of the Variaciones brillantes sobre la introducción from Norma by Bellini, op. 27. When in the ones based on the Himno de Riego he starts with an appropriate “Tempo di Marcia” and writing that remembers the instrumentation of a band, here the composer writes “Larguetto” and the writing shows that his inspiration in the Opera is further than just the title. Passages like the cantabile of bar 15, shows the influence of Italian Bel-canto applied to his pianism.

The themes of the variations are usually presented in a tempo moderato (Andante, Marziale, Tempo di Marzia) and has their origin in a concrete fragment or song coming from the Spanish culture (as the Himno de Riego [Riego´s Anthem]) or the Opera (in this case either Norma by Bellini or Il Crocciato di Egitto by Meyerbeer). They are structured in two parts, where the first one begins and ends in the tonic and the second one begins in the dominant to end in the tonic. The phrases are usually regular and symmetrical (four-eight-sixteen bars) and are slightly varied through the melodic profile or rhythm. The themes are always exposed in a texture of melody with accompaniment, where the right hand plays the melody and the left hand does an adequate accompaniment to the character of the fragment.

General Rafael del Riego led a popular uprising against the monarch Fernando VII through the pronouncement of 2nd January 1820[32] which supposed the end of his kingdom (Six years of Absolutism, 1814-1820). The poem and music written in honor of that event are known as the anthem of Riego and was adopted by the defenders of the republic during the short periods of time that this political model was established in Spain[33]. Pedro Albéniz, although closely related to the Royal House, is positioned on this occasion in favor of the Constitution of 1812, defender of a constitutional monarchy and liberal political ideology, and against Fernando VII, absolutist monarch. The future Queen, Isabel II will be identified with the liberal ideology as well.

The music that has come down to us as Riego´s Anthem is based on the 6/8 rhythm of the contradanza, as most of the anthems after the Independence War. In the case of Riego´s Anthem, the music was composed shortly after the text and its authorship is not clear. Traditionally it has been said that it was composed by José Melchor Gomis because there were published several versions of the anthem under his signature since 1822.

The other two variations chosen as examples come from different fragments of Bellini's opera Norma. The theme of the Variations op. 27 proceeds from the Andante mosso of the introduction to the first Act of the opera; and the theme of the Variations op. 33 proceeds from the duet (second scene) of the second act.

As we can see if we compare both excerpts from the last case, they are not written in the same key. After the analysis of his music, it is possible to affirm that this way of quoting the material taken from an opera is not very usual. They are much more commons the literal quotes: exact tonality and rhythm.

Within the repertoire analyzed, the number of variations found next to the theme moves between three and five. All of them have in common that they are based on a generator element, normally rhythmic, and that maintain, in its immense majority, the melodic profile and the harmonic and formal structure of the theme. The variations are conceived as an improvisation on the theme and are quite contrasting in tempo, character and even figuration.

All of them are written in the same measure (with the exception of the third variation of the Variaciones sobre la Introducción from Norma by Bellini, op. 27) and the most demanding part usually falls on the right hand (not so much in the Variations sobre el himno de Riego, op 28, where the second variation presents the theme in the left hand and the third presents it distributed between both hands).

The first two variations are always written in the same tempo (or very close) although they present different characters. We can also find a slower variation, usually the third one (the fourth in the case of the Variaciones sobre el himno de Riego, op 28), which is also in minor mode).

The coda is the section of the variations with greater formal and expressive freedom. It is conceived as a transitional section and it seems to have its origin, more than in any other fragment of these pieces, in the improvisation. Surprising modulations based on relationships of Dominant (often between tonalities which are not so close), experimentation in writing (through written-out and linked trills) and cadenzas fill these pages.

The purpose of the section can be diverse. Sometimes they are presented as emotional oasis which offers a character contrast with the rest of the works. In other cases, it seems to be an attempt to provide a structural unification with the introduction and/or the theme, and, sometimes, it can also be conceived as a kind of preparation for the finale, reflect in the tempo increase and the difficulty of the writing.

The finale is often the longest and most demanding section of the entire work. It is, at least, as extensive as the rest of the composition (if not more) and contains the most difficult pianistic elements of his language.

This last section is, in itself, multisectional and it usually begins with a variation of the theme. Within these pages, it is possible to find a considerable variety of pianistic designs and many ways of using them. An example of this can be the finale of the Variaciones brillantes sobre la Introducción of Norma by Bellini, op. 27.

However, there is no doubt that the most elaborate of the finales found in his sets of variations in the finale of Variaciones brillantes sobre el himno de Riego, op. 28. Structured in several contrasting sections, some of them are built with thematic material. In fact, the last two of them are thought to accompany first a soloist's voice and then a whole choir who sings the Anthem one last time as a farewell.

Undoubtedly, the Variaciones sobre un tema de Riego, op.28 are his most achieved set of variation. Its originality reflected through the formal innovations and the creative and concrete use of character indications, and the incredibly demanding writing, especially from the finale, makes this work unique within his catalog. In addition, it can certainly be compared to his most accomplished works and that can be considered one of the most important works within the genre in the context of the Spanish piano of the 19th century.

|29] Maria Nagore Ferrer. El lenguaje pianístico de los compositores españoles anteriores a Isaac Albéniz(1830-1868). Universidad Complutense de Madrid. P. 32.

[30] Laura Cuervo. El piano en España (1800-1830): repertorio, técnica interpretativa e instrumentos. PhD thesis directed by Cristina Bordás and María Nagore. Facultad de Geografía e Historia de la Universidad Complutense de Madrid. Madrid, 2012. P. 60.

It can be found online on:

https://eprints.ucm.es/17068/1/T34027.pdf

[31] Pronouncement:

“Spain is living at the mercy of arbitrary and absolute power, exercised without the least respect to the fundamental laws of the Nation. The King, who owes his throne to all those who fought in the War of Independence, has not sworn, however, the Constitution, a pact between the Monarch and the people, the foundation and incarnation of every modern nation. The Spanish Constitution, fair and liberal, has been elaborated in Cádiz, between blood and suffering. But the King has not sworn and it is necessary, for Spain to be saved, that the King swear and respect that Constitution of 1812, legitimate and civil affirmation of the rights and duties of the Spaniards, of all Spaniards, from the King to Last Labrador [...]

Yes, yes, soldiers; the Constitution. Long live the Constitution!”

[32]The Anthem of Riego was the Spanish National anthem during the Trienio Liberal (1820-1823), the first (1873-1874) and the second republic (1931-1939).