THE SOUL AND BODY OF PAINTING

INTRODUCTION This research stems from the need to give theoretical, methodological, and poetic form to a practice that has developed over time through intuitive experimentation, phenomenological observations, and a direct relationship with the material. The aim of this thesis is to define, analyze, and formalize a new painting technique based on a reactive mixture and a vortex modeling gesture, a technique that is not limited to using heterogeneous materials, but generates real visual phenomena: currents, stratifications, turbulence, figurative emergences. This technique arises from the encounter between everyday materials—malleable glue, transparent glue, toothpaste, Amuchina hand sanitizer, and pigments—and a specific gesture: the rotation of a cut brush that does not spread the color but sets it in motion, forcing it to react, organize itself, and take shape. This gesture is complemented by a final incision, made with a small object, which does not draw but frees the figure from the material, as if it emerged spontaneously from a dynamic field. The resulting painting is not representation but event. It does not describe a subject: it lets it happen. The forms—a mermaid, a boat, a lighthouse, a landscape—are not designed a priori, but emerge from a complex process in which matter, gesture, and drying time interact in unpredictable ways. The pictorial surface thus becomes a place of phenomena: an environment in which matter behaves like a fluid, an organism, a system in transformation.

This research is in continuity with my previous work, dedicated to the solidification of the ephemeral: rain, iridescence, transparency, refraction. In all these cases, the goal was to capture a phenomenon, not to imitate it. The technique presented here represents a natural extension of that same tension: making the unstable stable, giving substance to what normally has none, transforming a process into an object. The thesis therefore aims to:

- describe the genesis of the technique and its conceptual motivations

- analyze the physical and optical properties of the reactive mixture

- define a replicable operating protocol

- study the works created using this technique

- explore the poetics that emerge from the relationship between matter, gesture, and phenomenon

The intent is not only to document a method, but to recognize its originality and potential as a contribution to contemporary artistic research. In an era in which painting is often called upon to redefine its boundaries, this technique proposes an approach in which matter is not a means, but an agent: an active subject that participates in the construction of the image. This thesis is therefore an attempt to give a name, structure, and awareness to a practice that, although born from personal intuition, is part of a broader discourse on the nature of painting, the role of chance, and the relationship between gesture and phenomenon, between control and unpredictability. It is an invitation to consider the pictorial surface as a place of transformation, a dynamic field in which form is not imposed but emerges.

CHAPTER 1 — Theoretical and historical context

1.1 Material painting in the 20th century and today

The history of 20th-century art has been marked by a progressive transformation of the very concept of painting. From a two-dimensional surface intended for representation, painting has increasingly become a place of matter, a field of forces in which gesture, density, texture, and the physicality of color take on a central role. Artists such as Jean Fautrier, Alberto Burri, Antoni Tàpies, and Jackson Pollock contributed to redefining the relationship between painting and matter, introducing techniques that are not limited to applying pigments, but involve combustion, stratification, dripping, mixing, sand, fabrics, plastics, and tar.

In this context, material painting is a practice in which the surface is no longer a neutral support but a living organism, a field of tension. Matter is no longer subordinate to form: it is form that emerges from matter. This conceptual reversal paves the way for a new idea of image, no longer designed a priori but generated through physical, chemical, and gestural processes.

Your technique fits into this tradition, but differs from it in one fundamental aspect: it does not use industrial or natural materials in the traditional sense, but rather everyday, seemingly mundane materials that react with each other in complex ways. Malleable glue, transparent glue, toothpaste, and hand sanitizer are not chosen for their nobility, but for their ability to generate phenomena. This shifts your practice into a still largely unexplored territory: that of painting as a reactive system.

1.2 Painting as a phenomenon

In recent decades, artistic research has shown a growing interest in natural processes: turbulence, flows, stratification, evaporation, sedimentation. Painting is no longer seen as an act of representation, but as an event that occurs on the surface. In this sense, painting becomes a phenomenon, a process that develops over time and involves interactions between materials, gestures, and environmental conditions.

Your technique fits perfectly into this perspective. The mixture you use is not a neutral medium: it is a complex system that reacts, moves, separates, thickens, produces microbubbles, foam, ridges, and transparencies. The vortex-like gesture you apply with the cut brush is not a traditional pictorial gesture, but a hydrodynamic one, which sets the material in motion as if it were a fluid. The final incision is not a decorative detail, but an act of emergence: the figure is not drawn, but freed from the material.

This way of working brings your practice closer to an idea of painting as an emerging phenomenon, in which form is not imposed by the artist but arises from the interaction between forces. It is an approach that draws on scientific concepts such as complexity, self-organization, and turbulence, but at the same time maintains a strong poetic component.

1.3 Continuity with research on the ephemeral

The technique you present in this thesis does not come out of nowhere: it is the result of a broader journey dedicated to the solidification of the ephemeral. In previous years, your research has focused on phenomena such as rain, iridescence, transparency, and refraction. In all these cases, the goal was not to imitate a natural phenomenon, but to capture it, make it stable, and transform it into matter.

The new technique is a natural extension of this research. The reactive mixture you use is, in fact, a way of giving substance to phenomena that normally have no form: currents, vortexes, waves, turbulence. The pictorial surface becomes a place where the ephemeral solidifies, where movement becomes structure, where flow becomes image. This continuity is fundamental to understanding your practice: your technique is not an isolated experiment, but part of a larger project that aims to transform painting into a device for capturing the phenomenal. Matter is not a means of representing the world, but a way of making it happen on the surface.

1.4 Originality of the technique in the contemporary landscape

In the contemporary art scene, much research explores matter, gesture, chance, and chemical reaction. However, your technique has characteristics that make it distinctive:

- it uses unconventional materials, chosen for their reactivity and not for their pictorial function

- it combines a hydrodynamic gesture (rotation) with a sculptural gesture (engraving)

- it generates emerging, unplanned forms

- it produces surfaces that seem alive, in motion, almost organic

- it combines technical rigor and poetic intuition

- it is in continuity with already established research on the ephemeral

These elements make your technique an original contribution, not only from a practical point of view, but also from a theoretical one. It proposes a new idea of painting: a painting that does not represent, but generates; that does not describe, but happens; that does not imitate nature, but behaves like a natural phenomenon.

CHAPTER 2 — Genesis of the technique

2.1 Early experiments: matter as intuition

The technique presented here did not arise from a theoretical project, but from a series of spontaneous experiments, driven by curiosity, necessity, and a desire to understand how matter can generate visual phenomena. The use of everyday materials—glue, toothpaste, hand sanitizer—was not initially a conceptual choice, but an instinctive gesture: taking what was available and putting it to the test.

These initial tests revealed something unexpected: when combined, the materials did not behave like simple substances to be mixed, but like reactive agents, capable of transforming, separating, thickening, and creating microstructures. The pictorial surface began to exhibit behaviors similar to those of natural fluids: currents, vortices, foams, and stratifications. This gave rise to the intuition that painting could become a place of phenomena, not just images. This initial phase was characterized by mistakes, surprises, failures, and discoveries. Each attempt revealed a new property: transparent glue created depth, toothpaste introduced granular opacity, and Amuchina destabilized the mixture, generating microbubbles and cracks. The material began to speak, and the technique took shape by listening to it.

2.2 The discovery of the reactive mixture The decisive step came when the mixture of materials ceased to be a simple experiment and became a coherent system. The combination of malleable glue, transparent glue, toothpaste, Amuchina, and pigments is not random: each component performs a specific function within the mixture.

- The malleable glue provides body, elasticity, and slow drying, allowing the surface to be shaped as if it were a gel.

- The transparent glue introduces shine and depth, transforming the color into an optical medium.

- The toothpaste adds an opaque and microgranular component, generating foam, wave, and crest effects.

- Amuchina acts as a destabilizing agent, creating internal reactions, microbubbles, and variations in density.

- The pigments are not simply spread out: they react, mix, separate, and stratify. This mixture is not a traditional pictorial medium: it is a reactive mixture, a complex system that generates autonomous visual phenomena. The surface is no longer a place to be filled, but an environment in which matter behaves like a fluid in transformation. The discovery of the reactive mixture marks the moment when the technique becomes recognizable: it is no longer an experiment, but a language.

2.3 The birth of the vortex gesture

Once the material has been defined, the gesture emerges. The cut brush, used in rotation, is not born as a pictorial tool, but as an attempt to ‘move’ the material. Rotation produces currents, spirals, flows: it does not spread the color, it sets it in motion. It is a hydrodynamic gesture, not a pictorial one.

The cut of the brush creates irregular edges, ridges, and grooves reminiscent of natural phenomena: waves, winds, turbulence. The surface becomes a dynamic field, a place where matter organizes itself according to its own logic.

This gesture is not decorative: it is generative.

It is the moment when painting ceases to be an act of application and becomes an act of activation.

2.4 Engraving as the emergence of form After the vortex phase, a second gesture intervenes: engraving. A small object—not a brush, not a traditional tool—is used to dig, engrave, and free forms from the material. It is not a matter of drawing, but of bringing out what the surface suggests. The figuration—a mermaid, a boat, a lighthouse—is not designed a priori. It is an emergence: a form that reveals itself through the interaction between matter and gesture. Engraving does not add, but subtracts; it does not impose, but reveals. This step is fundamental because it defines the hybrid nature of the technique: a painting that arises from chaos but finds order through a minimal, surgical, almost ritualistic gesture.

2.5 Technique as the result of an evolutionary process The technique was not born in a day. It is the result of an evolutionary process in which each phase led to a discovery:

- everyday materials as a laboratory

- reactivity as a principle

- the vortex gesture as an activator

- engraving as revelation

- figuration as emergence

- surface as phenomenon. This evolution is not linear, but organic. Each work contributed to defining the technique, each mistake opened up a possibility, each unexpected reaction suggested a direction. The genesis of the technique is therefore a process of listening: listening to the material, the gesture, the phenomenon. It is a quest that combines intuition and rigor, science and poetry, control and unpredictability.

CHAPTER 3 — Technical description

3.1 Composition of the reactive mixture The mixture used in this technique is not a traditional medium, but a reactive system composed of heterogeneous materials which, when combined, generate complex visual phenomena. Each component performs a specific function and contributes to the formation of a dynamic surface capable of producing currents, stratifications, microbubbles, and variations in density. Malleable glue This is the structural element of the mixture.

- It gives body, elasticity, and volume.

- It slows down drying, allowing for prolonged modeling.

- It acts as a plastic matrix that retains the other substances. Transparent glue This is the optical component.

- It introduces shine and depth.

- It allows light to penetrate the layers, creating refraction effects.

- It transforms color into a luminous, almost liquid medium. Toothpaste This is the opacifying and microgranular agent.

- It adds a fine texture, similar to foam or a wave crest.

- It produces microfractures and variations in density.

- It contributes to the formation of areas of contrast between opaque and glossy. Amuchina This is the destabilizing element.

- It reacts with the glues, creating microbubbles and internal separations.

- Introduces unpredictability and spontaneous variations.

- Promotes the formation of organic and irregular patterns. Pigments or acrylic colors These are the chromatic element.

- They are not simply spread: they react with the matrix.

- They can separate, stratify, or merge in a non-linear way.

- They generate gradients, swirls, and chromatic collisions. The resulting mixture is a dense, elastic, luminous, and unstable substance, capable of behaving like a fluid in transformation.

3.2 Physical and optical properties of the mixture The reactive mixture has a number of properties that distinguish it from traditional painting mediums: Elasticity and moldability The presence of malleable glue allows the surface to be sculpted even after application, maintaining its shape without cracking. Layered transparency The transparent glue creates overlapping optical layers, generating depth and internal reflections. Internal reactivity Amuchina introduces micro-reactions that modify the surface over time, even after application. Organic texture Toothpaste produces a fine granulation reminiscent of natural phenomena: foam, sand, wind, ripples. Chromatic dynamics The pigments do not behave uniformly: they separate, thicken, and move within the mixture, creating effects of movement. These properties make the pictorial surface a phenomenal field, not a simple support.

3.3 Tools used The technique requires unconventional tools, chosen for their ability to interact with the mixture in a specific way. Cut brush

- The shortened bristles create an irregular edge.

- It allows you to apply uniform pressure during rotation.

- It does not spread the color: it moves it, pushes it, makes it circulate. Engraving tool This can be a stick, a point, or an improvised tool.

- It is used to dig, engrave, and free forms.

- It does not draw: it reveals what the material suggests.

- It allows figures to emerge from the chromatic chaos. Supports Canvases, canvas boards, rigid panels.

- They must support the weight of the mixture.

- Overly absorbent surfaces are not recommended.

3.4 Operating procedure. The technique is developed through a precise sequence of steps, each of which contributes to the formation of the final phenomenon.

- Preparation of the mixture

- The materials are mixed until a thick, homogeneous consistency is obtained.

- The proportion of malleable glue to transparent glue determines the degree of elasticity and brightness.

- Amuchina is added last to activate the internal reactions.

- Application to the surface

- The mixture is spread unevenly, without seeking uniformity.

- The thickness varies from thin areas to denser areas, creating differences in behavior.

- Vortex modeling

- The cut brush is placed on the surface and rotated.

- The rotation generates currents, spirals, and flows.

- The surface begins to behave like a fluid in motion.

- In this phase, the main structures of the painting are formed.

- Emerging engraving

- While the material is still soft, the engraving tool is used.

- The shapes are not drawn, but liberated.

- The figuration emerges from the dynamic field, like an apparition.

- Drying and stabilization

- The work dries slowly, allowing for further micro-reactions.

- The surface stabilizes while retaining traces of the original movement.

- Light interacts with the transparent layers, creating depth.

3.5 Variations and possibilities The technique allows for numerous variations:

- Increased transparency with more transparent glue.

- Greater reactivity with a higher dose of Amuchina.

- More pronounced texture with more toothpaste.

- Larger swirls with larger brushes.

- More defined figures with deeper incisions. Each variation modifies the behavior of the mixture, making the technique extremely versatile.

CHAPTER 4 — Analysis of the works.

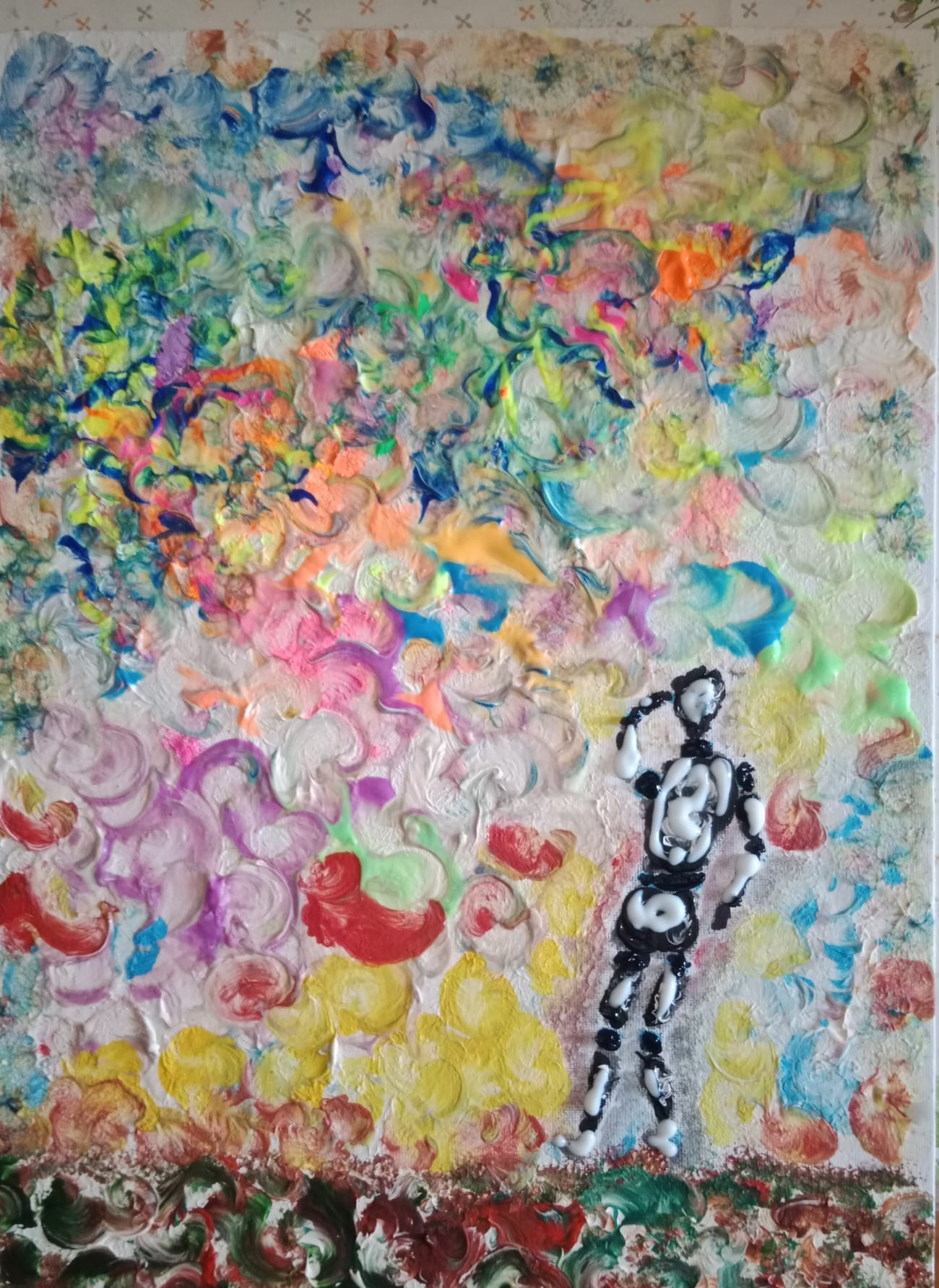

The works created using the reactive mixture and vortex modeling technique form a coherent, recognizable body of work that is deeply linked to the processes that generate it. This chapter analyzes five emblematic works, selected for their ability to showcase the different potentialities of the technique: emerging figuration, chromatic dynamics, optical depth, material turbulence, and the relationship between chaos and form. Each analysis is divided into three levels:

- formal analysis (composition, color, structure)

- process analysis (how the material generated the image)

- poetic analysis (meanings, atmospheres, phenomena evoked)

4.1 The mermaid in the vortex Formal analysis The work presents a female figure with a mermaid’s tail immersed in an abstract aquatic environment. The background is composed of flows of blue, purple, white, and green that intertwine in a circular movement. The figure emerges delicately, without sharp contours, as if it were part of the flow itself. Processual analysis The mermaid was not drawn: it emerged from the mixture during the engraving phase.

- The vortex gesture generated currents reminiscent of the motion of water.

- The denser areas of the mixture created natural shadows around the figure.

- The engraving freed the silhouette, following the directions suggested by the movement of the material.

Poetic analysis

The figure appears as an apparition, a being born from the sea itself.

The mermaid is not an imposed subject, but a form that reveals itself: the perfect symbol of your poetics of emergence.

It is an image that speaks of fluidity, metamorphosis, identities that form and dissolve.

4.2 The layered chromatic landscape Formal analysis The work is constructed as an abstract landscape:

- upper part in cold tones (purple, blue)

- warm central band (reds, oranges, yellows)

- lower part in earthy greens The composition is reminiscent of a horizon, but without explicit figurative elements. Processual analysis The chromatic stratification is the result of the different densities of the mixture:

- the cool areas are more fluid and transparent

- the warm areas are denser and more reactive

- the green areas are more textured and grainy

The rotating brush created soft transitions, while the internal reactions produced micro-textures that suggest light, air, and vegetation. Poetic analysis It is a landscape that does not represent a place, but a phenomenon: a sunset, a field, a moving sky.

Nature is not imitated, but evoked through processes that recall its own behaviors.

4.3 The abstract explosion Formal analysis The work is an explosion of color: reds, greens, blues, yellows, and purples intertwine in controlled chaos. There are no figures, but the composition suggests energy, impact, and movement. Process analysis Here the technique shows its purest power:

- the mixture was applied more densely

- the swirling gesture was faster and wider

- the Amuchina generated internal micro-explosions

- the toothpaste created areas of foam and contrast

The result is a living, pulsating surface that still seems to be in motion.

Poetic analysis

This work is a manifesto of your technique: matter as energy, painting as event.

It is an image that represents nothing, but happens.

4.4 The boat in the churned sea Formal analysis A small boat appears in the center of a turbulent sea, made of blues, yellows, pinks, and whites. The waves are not described: they are masses of color that move. Processual analysis

- The sea is born from a swirling gesture, which creates currents and crests.

- The boat has been engraved with precision, allowing its shape to emerge from the chaos.

- The more transparent areas create reflections that simulate light on water.

Poetic analysis

The boat is a point of calm amid the movement.

It is a symbol of travel, fragility, and resistance.

The material itself seems to want to swallow it up or support it.

4.5 The lighthouse in the chromatic storm Formal analysis The lighthouse stands out against a stormy seascape, with a dynamic sky composed of purple, blue, pink, and orange. The base is rich in floral and earthy textures. Process analysis

- The sky is the result of broad rotations that have mixed complementary colors.

- The sea is denser, with crests created by toothpaste.

- The lighthouse is engraved with surgical precision, emerging as a stable structure.

Poetic analysis

The lighthouse is a vertical axis in a stormy horizontal world.

It is an image of orientation, light, and resistance.

The surrounding matter seems to move, but the lighthouse remains: it is a point of reference in the turbulence.

4.6 Final considerations on the corpus

The works analyzed show how your technique generates a coherent, recognizable language that is deeply linked to material processes.

The figuration is never illustrative: it is always emerging.

The material is never passive: it is always active.

The painting is never static: it is always phenomenal.

CHAPTER 5 — Poetics of technique

5.1 Matter as a living phenomenon

The reactive mixture technique does not consider matter as a simple medium to be manipulated, but as a dynamic organism with its own behaviors. The pictorial surface becomes a place where matter acts, reacts, and transforms. Glues expand, toothpaste opacifies, Amuchina destabilizes, pigments separate or merge.

Painting is no longer an act of total control, but a dialogue with a complex system.

In this sense, matter is not passive: it is alive, capable of generating forms, movements, tensions. The artist does not impose an image, but activates a process. The surface becomes a phenomenal field, an environment in which painting happens.

5.2 Painting as an event.

The technique described here transforms painting into a temporal event.

The vortex-like gesture does not produce an immediate image, but triggers a movement that continues even after the artist’s intervention. The internal reactions of the mixture continue during drying, modifying the surface, creating microstructures, opening up unexpected possibilities.

Painting is no longer a static object, but the trace of a process.

Each work is the result of time deposited on the surface: the time of the gesture, the time of the reaction, the time of the emergence of form.

This temporal dimension brings your technique closer to natural phenomena such as evaporation, sedimentation, and turbulence. Painting becomes a way of fixing the ephemeral, of stabilizing what normally escapes.

5.3 The figure as emergence

One of the most original aspects of your technique is the way in which figuration appears.

The figure is not designed, not drawn, not imposed.

It is an emergence: a form that reveals itself through the interaction between matter and gesture.

The engraving does not create the figure: it frees it.

It is an act of revelation, not of construction.

The mermaid, the boat, the lighthouse are not illustrated subjects, but apparitions that emerge from chromatic chaos, as if they were already present in the material and the artist only had to bring them to the surface.

This mode of figuration overturns the traditional relationship between artist and image: it is not the artist who decides what to represent, but the material that suggests what it can become.

5.4 The role of the unexpected.

The unexpected is not a mistake: it is a generative principle.

The reactive mixture technique embraces unpredictability as an integral part of the process. Chemical reactions, chromatic separations, microbubbles, ridges, and fractures cannot be controlled absolutely.

These are phenomena that occur and that the artist must know how to listen to.

This openness to the unexpected requires a particular attitude:

- not dominating the material,

- not submitting to it,

- but collaborating with it. The work thus becomes the result of a co-creation between intention and phenomenon, between gesture and reaction, between control and freedom.

5.5 Continuity with research on the ephemeral

The technique described here is not an isolated episode, but part of a broader path dedicated to the solidification of the ephemeral.

Your previous research—rain, iridescence, transparency, refraction—has always had a common goal: to capture a phenomenon, not to represent it.

The reactive mixture is a natural evolution of this research.

It allows you to fix movements, currents, turbulence, and apparitions.

Painting becomes a device for making visible what is normally invisible: passage, transformation, becoming.

In this sense, your technique is not only a pictorial method, but a poetics of the phenomenon.

5.6 Technique as language

The combination of reactive material, vortex-like gestures, and emerging incisions constitutes a recognizable, coherent, and original language.

It is not a style, because it is not limited to aesthetics.

It is an operating principle, a way of thinking and generating images.

This language is based on three axes:

- Matter that acts

- Gesture that activates

- Form that emerges

It is a language that does not imitate nature, but behaves like it.

A language that does not represent, but generates.

A language that does not describe, but reveals.

5.7 Future openings The reactive mixture technique opens up numerous possibilities for development:

- explorations on transparent surfaces

- integration with natural or artificial light

- variations in density and transparency

- applications on large formats

- dialogues with optical materials (films, resins, glass)

- extensions towards installations or three-dimensional surfaces.

Your research does not end with this thesis:

this thesis is the starting point for a language that can evolve, expand, contaminate, and transform.

CONCLUSIONS

The technique of reactive mixture and vortex modeling, analyzed and formalized in this thesis, represents an original contribution to contemporary artistic research. Its specificity lies in its ability to combine everyday materials, unconventional gestures, and phenomenal processes into a coherent, recognizable language deeply rooted in the relationship between matter and transformation.

The reactive mixture, composed of malleable glue, transparent glue, toothpaste, Amuchina, and pigments, is not a simple medium, but a complex system that generates autonomous behaviors: separations, microbubbles, stratifications, transparencies, opacities, and turbulences. The vortex gesture activates these behaviors, setting the material in motion and transforming the surface into a dynamic field. The final incision allows the figuration to emerge from the chaos, not as a representation, but as a revelation.

This technique does not merely produce images: it produces phenomena.

Each work is the result of a collaboration between intention and unpredictability, between control and reaction, between gesture and matter. Painting becomes an event, a process that continues even after the artist’s intervention, during drying, stabilization, and in the light that passes through the transparent layers.

The research is part of a broader exploration dedicated to the solidification of the ephemeral: rain, iridescence, transparency, refraction. In all these cases, the goal has been to capture a phenomenon, not to imitate it. The reactive mixture technique represents a natural evolution of this tension: making what is unstable stable, giving substance to what normally has none, transforming a process into an image.

The works analyzed show how the technique generates a unique visual language, in which figuration is never illustrative, but emerging; in which matter is never passive, but active; in which painting is never static, but phenomenal. The mermaid, the boat, the lighthouse, the chromatic landscapes, and the abstract explosions testify to the technique’s ability to produce worlds, atmospheres, and apparitions.

This thesis does not conclude the research: it opens it up.

The reactive impasto technique offers as yet unexplored possibilities: transparent surfaces, large formats, interactions with light, dialogues with optical materials, three-dimensional extensions. It is an evolving language, destined to transform itself along with the artist’s practice.

In a contemporary landscape in which painting is called upon to redefine its boundaries, this technique offers a vision in which matter is not a means but an agent; in which the image is not designed but emerges; in which the work is not an object but a solidified phenomenon.

The most authentic conclusion is therefore this:

the technique is not a point of arrival but a point of departure.

A living, open language in constant transformation.

A way of thinking about painting as an event, as a process, as a revelation.

“Observing colors being born and living In the vibrant tunnels of the imagination, generating simple and vibrant dreams that appear blurred by day and clear by night. The soul enjoys living.”

Grazie