About exchanging a portrait

"Art is the immediate realization of intent."

John Dewey

Introduction

20130805

Tomorrow Börje Lindberg will come to my studio and I will start to make his portrait. We have been discussing this project for the last 3 or 4 years, but until now we have not come so far as actually doing it. I didn't prioritise it and procrastinated. I was reluctant–even though it was my idea from the start. On a hot summer day in Christinehof park I saw him working on a sculpture with a bare upper body. His characteristic head on top of his naked torso inspired me and I asked him more or less spontaneously if I could do his portrait. He immediately said yes.

Börje Lindberg is an elderly, locally known and appreciated sculptor. Most often he works in wood, but also in bronze, steel and other materials. His style is impressionistic, pretty rough and sketchy, 20th Century classic, the human figure is always present in his work. Despite his age–Börje is 85–he is remarkably vital. He is still at work, he has a girlfriend, dances the Tango and enjoys life. When I called him yesterday to confirm our appointment, he told me he felt reborn, ready for something new, which I learned to find a typical comment for him.

He took a remark of my wife to heart: she said that we should make each others portraits. At first I thought of doing his portrait, now he will do mine as well, and I think that is both challenging and fun! Börje told me it was a long time since he made a real portrait and he is thrilled to do it again. He also wondered whether he would work in wood or in my material, clay. That, I thought, was an interesting idea. What would happen if I were to do his portrait in wood? I have been curious about working in wood and I have more or less planned to try it once in my lifetime. I have never worked in wood before, but I have carved in stone and sand. If he makes my portrait in the material I typically work with and I make his portrait in his, this exchange project will get a dimension that I think is challenging. In addition, working with this other material will be placed in a context and it wouldn't be completely out of the blue.

Background

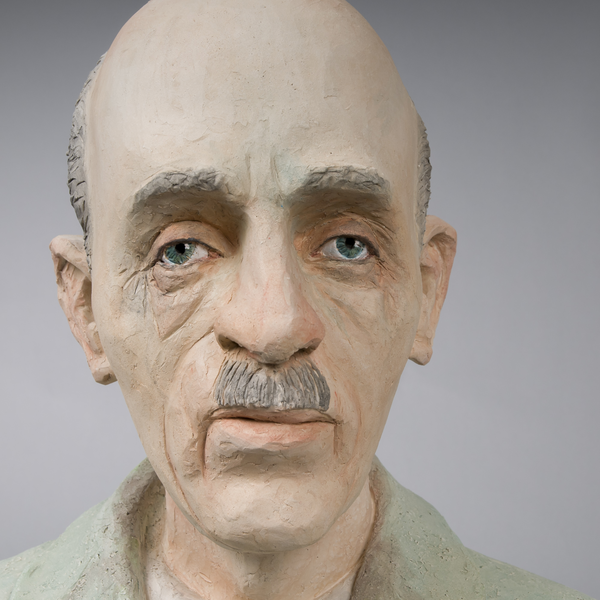

I work with series of portrait sculptures and abstract drawings. My series of sculptures are most often based on photographs from archives and deal with human vulnerability. For example, I have worked with series of portraits on immigrants who during the Second World War where arrested by the Gestapo in Vienna on the accusation of being "lazy" or having "illegal relations" (picture). Another series are portraits of Jewish children who were deported to the concentration camps, "French Children of the Holocaust", life size portraits of children in a naturalistic style (picture). For these series of portraits I make use of pictures from archives, books or internet and over the years I have become seasoned with the method that I apply.

I have taught myself portraiture and I want to make portraits that are credible and naturalistic in their appearance. These portraits are not isolated portraits, portraits at their own right or portraits an sich, but rather actors on a stage in a story I want to tell. It is a narrative portraiture. I want the attention of the spectator to be drawn to the story behind these portraits, not to the actual portraits, nor to my interpretation of the portrayed, nor to the particular technical details of how these portraits came about, as the subject matter of these sculptures is not how they came about. Even though the process of making is without any doubt present and can be read as a separate content layer, the subject matter lay outside the actual physical portrait. Yet, technically I try to get close to the people I portray and I pay a lot of attention making them. This seems to be contradictory, but the perception of these sculptures is influenced by the credibility of my interpretation, by the degree in which they appear to be realistic. The more the spectator accepts the portraits as actors in a story, instead of as portraits an sich, the more credible this story is.

In 'Gender is Burning, questions of appropriation and subversion', Judith Butler states that an artwork (in her text a performative act of drag) is successful only if it cannot be 'read'. This is, if the form, intention, content and execution are convincing to an extent that it is not questioned as a work of art, but "appears to be a kind of transparent seeing". (Butler, 1993, p129) In other words, if an artwork is questioned as work of art, it fails. In that sense, I would like my portraits to be convincing, both as portraits an sich, in the way they came about (the technical details) and in the narrative they represent.

With my portraits I would like to evoke an experience of what Emmanuel Levinas calls "the epiphany of the face", the intangible being of man that goes beyond its outer appearance. We have a moral obligation: if we reduce the Other to his or her outer appearance, we are unjust. "Ethics starts in resisting the temptation to diminish the Other to the image we have through our perception." (Guwy, 2008, p89-90). In my portraits I want to visualise the Other as a vulnerable human being, but as an artist/creator I don't want to appear in between the portrait and spectator, since that would evoke questions on the coming about of these sculptures – which would cause the artwork to fail. If I can make a portrait that is not reduced to outer form but calls forth an experience of something intangible behind, I think I can rightfully say that I have brought this portrait to life. In this setting a realistic portrait is the beginning of a story of human vulnerability (picture).

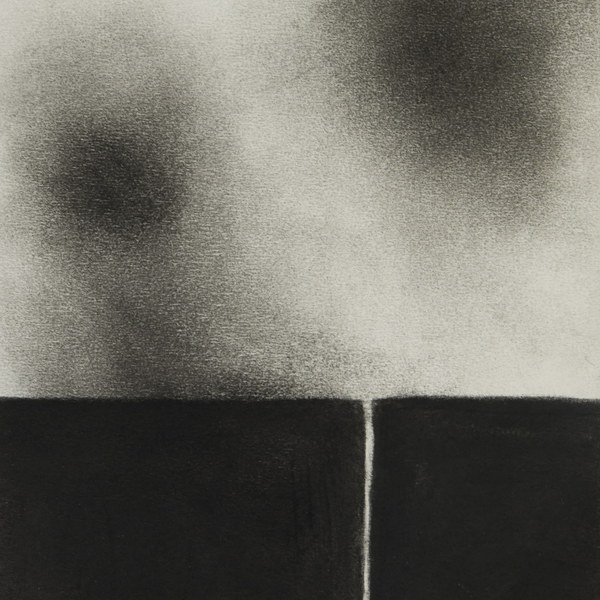

Compared to my sculptures, I have both conceptual, formal and methodological a diametrically opposite approach to my drawings. The last years I have reestablished my relation to my drawings as a complement to my sculpture after many years of neglect. At one time I thought it was so problematic to contextualise my drawings that I stopped working with them. Now I realise that my sculptures refer to the outer world and my relation to the social context in that outer world and that my drawings are foremost introspective and contemplative by nature. Despite the fact that my drawings are non-figurative and abstract and hold a formal contrast to my sculptures, I feel that there is a strong connection on an emotional level between these two bodies of work. (picture)

My objectives with this project — how to renew my artistic proces.

Over the years I have developed a very specific way of working by making series of realistic portrait sculptures in ceramics, based upon pictures from archives that I appropriate to my needs. These series bring forth narratives on human vulnerability and are referring to anthropology, sociology, history, psychology and art.

I have worked for many years with these appropriated portrait pictures, using them for measuring the facial features of the portrayed and transferring these measurements to my sculptures, creating likening portraits through a working method that I learned to control in every detail. This method has functioned for me both conceptually and organisationally, since I feel the need for a structured working environment to sustain my mental stability.

The downside of this structured environment is that I experience mental and artistic blocks that manifest themselves through reiteration and difficulties to let my work 'flow'. If I am in a negative state of mind, I perceive my process as habitual and entrenched. Furthermore, I feel a constant need for a conceptual framing of my work and find it hard to use a more intuitive approach. This conceptual framing has not only brought advantages like distinct and clearly defined bodies of works, but also a fear to let go, a fear that I cannot make valuable work outside my well defined box and consequently, a fear that I need to be able to justify every single step I make. Sometimes it is difficult to trust my own artistic guts.

Of course, the days of unarticulated, raw artistic beasts are over (if they ever existed) nowadays artists are expected to be able to verbalise their works, hence the rise of artistic research, doctorate programs in art and a much more verbal culture around art than I experienced a 25 years ago. I don't want to proclaim that one should not be verbal about one's work, or that conceptual framing kills an intuitive approach, but for me personally the downside of my controlled environment lies in a felt inability to loosen up this conceptualised method of working. It is as if I don't allow myself to let go.

Another problem of my conceptual framing, as I see it, lies in my desire to control the perception of my work. I present a work that is complex and multilayered, but I tend to give a clear prescription of how to read it. As it is now, these works can be read in an anthropological, sociological or historical context and has references to other artists and art, but I would like to diffuse the interpretation, as I sometimes feel that I try to make everything accountable. I am seeking a visual language that can stand for itself.

Summarised, my main objective for this project is that I am seeking artistic renewal: I want to open up my process, aim for more artistic flow, challenge myself, widen my visual language and make work that is open for a more diffuse interpretation, where the visual can stand for itself.

Sometimes I long for the early days of my artistic explorations. I don't yearn for the actual works that I made–my work has become so much more advanced–but I long for the artistic attitude that I had, I long for the artistic curiosity, when everything was new, possible and exciting, when I explored every little sidetrack.

Text and method

I do not have a devised strategy for this project and text other than a will to be aware of my thoughts about my way of working.

I am not after a text in academic closed format, a text in which every element has a well defined place and structure, in which the author has a clear overview of what will come and offers a concise and elaborated piece of work. Instead, this text will follow my artistic process as well as being a part of its becoming, it is non-anticipatory: I have not formulated on forehand the what and how of this text. This writing gives shape to my thoughts, it is a text en taille directe: I will write and gradually it enfolds itself. That makes this text a part of my creative process and a reflection of it, it is both forming my thoughts about my work and reciprocally giving direction to my process. I will use free association as an instrument to create the possibility for unexpected content to surface. Mika Hannula says that it is not very productive to first make art and then use this art as an object for research. This would produce vague and introvert research. (Hannula: 2005, p58) In the method that I have in mind, I will deliberately enter a vague and introvert domain, being artist and researcher at the same time, trying to follow my process closely and describe as many aspects as I can come up with. I will not try to objectify, I want to get close to my thoughts.

Introspection as method is not common in academic research, neither is it in the field of artistic research. More common is to use research instrumentally, with an intend to have a clear outside perspective where the self is excluded, in an attempt to objectify and describe a problem or a "research question" that is beyond the personal. To me that feels awkward, impersonal and unproductive. I want to include the personal, since I want to follow, understand and articulate the actual coming about of my artistic process and how I reflect on it, since this reciprocally influences my process. The main focus is on my process, not beyond. An outside perspective is even in traditional research impossible to reach, since the observer/researcher is always included in the set-up of the apparatus and therewith in the outcome of the research. I understand that instrumental use of research is striven after in academic research, but I would like art—and for Heaven's Sake artistic research—to be a free-zone where other methods and ways of thinking are possible, where there is a place for the unexpected.

These journals are a collection of almost two and a half years of writing. Just as it goes: sometimes I felt the need of writing, to clear my mind or to get going and there were periods where I didn't make any note at all. After a year of working with this text I lost my appetite for it. I had quit my second course Artistic Research, thinking that it was not for me after all. At the time I only made random notes for myself, some connected to this project, others had nothing to do with it. When I decided to continue with this project, I went through these notes, translated relevant parts that were written in my mother tongue—Dutch—and implemented them, but obviously, this text has taken a different course from what I thought from the start.

"The biggest problem right now is that you don’t know what sort of fiction you are dealing with. You don’t know the plot; the style is not set. The only thing you know is the main character’s name. Nevertheless, this new fiction is reinventing who you are. Give it time, it’ll take you under its wing, and you may very well catch a glimpse of a new world. But you are not there yet, which leaves you in a precarious position.”

(Haruki Murakami, 2001: p 68-69)

page 1: Introduction

page 2: Meetings with Börje Lindberg

page 3: Intermezzo

page 4: Back to my project

page 5: Conclusion and References

The Polish farmer Felix Oginsky was arrested at his work place in Velm (Niederösterreich) on suspicion of “Refusal to work” and was registered on June 27th, 1940 by the identification department of the Gestapo Vienna.

ceramics and pigment, 2008