Meetings with Börje Lindberg

At work

20130813

Börje and I have had two meetings. We drank coffee and talked. We have scanned and probed each other. We have been in the kitchen and in the studio and we have posed for each other twice, one hour each time, and we have worked with our portraits. We have agreed on meeting once a week in my studio and we made a vague agreement that this project should not continue endlessly. There is a limitation in time, but we have not set any deadline. As long it is fun, it's good.

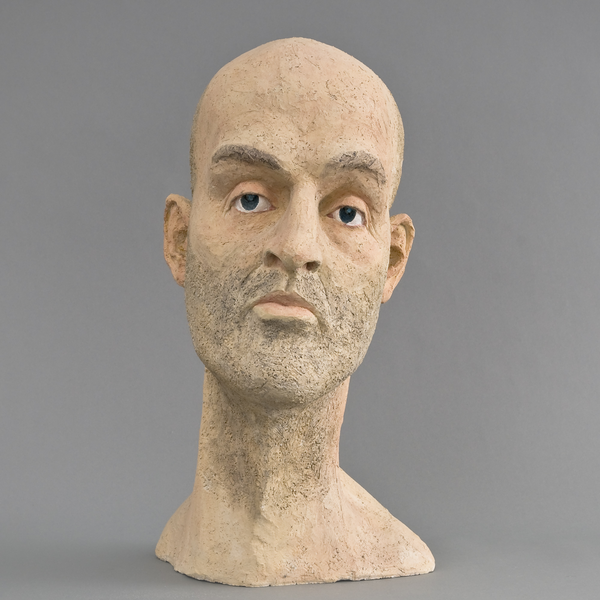

I am making a sketch in clay that I will transfer to wood at a later stage. I have decided not to use pictures, but solely work with my sculpture when Börje is sitting in front of me. Last time I worked this way was with a portrait of Oane Postma in 2003 (picture). Most the other portraits depicting a living person I have used pictures combined with posing. An exception to this method is the portrait of Viveka Adelswärd for example, (picture) where I only used pictures and she did not pose at all. Since I do not use pictures to construct my sculpture of Börje, I cannot fall back on my rational system of comparative measurements and therefor I need to trust my bare eyes. Until now this worked quite well: at the end of two sessions I measured the width and length of Börjes head with a calliper and I was accurate within a centimeter.

Oane's portrait might be the best portraits I have made of a living person sitting in front of me. It appeals to me both on an emotional and artistic level while he is very recognisable as Oane Postma and it occurs to me that this may be due to the fact that I did not use a measurement system. Maybe my idea that I need a reliable and rational working method is an idée fixe, motivated by fear of losing myself, surpassing my borders and becoming mentally unstable. Can I change this system, my working method, without getting derailed? When I started this project I asked myself how to change my process, now I ask myself: can I change it at all?

Börje wears spectacles and that is a problem. It is a characteristic pair of spectacles, dominating his face: a relatively heavy, black frame with fairly strong magnifying glass (picture). Spectacles are ordinary attributes on living people—we are used to looking at people who wear them. A persons face and eyes are constantly moving and so is the angle at which you look at him or her: this influences the how and what you see of a face through the spectacles of the wearer. I think it is a fascinating view, but impossible to catch in a static sculpture. The glasses enlarge or diminish the eyes and sockets, and even if you could catch this deformation in a sculpture, then it would only be seen from one specific angle, like in a bas-relief. If you look from another angle the deformation is different. This gives an absurd situation which you could exploit artistically if your name is Picasso, who combined multiple perspectives in one painting (picture), but it is impossible if you want to create a representational three-dimensional portrait. An additional problem is that you cannot make the frame in clay and even if you tried it would look awkward since there is no lens. Giving a sculpture real spectacles is unacceptable. I have never seen a convincing solution for this problem, at it's best it looks horrible. There might be a possible solution by making just a tiny bit of the frame, as for example in the sculpture of Theodore Rooseveld on Mount Rushmore, made under guidance of Gutzon Borglum (picture).

I have decided to skip Börjes glasses.

One of the most interesting aspects of working with a life model I think is that you can study your model unabashedly and at length. That which in daily life is considered to be blatant staring, awkward and most often not appreciated, is all of the sudden fully acceptable. You can scrutinise a picture, but it is never the same as studying a person sitting in front of you. A picture is and remains flat. The spatial form of a face can only be estimated approximately using a photograph. With a living model you can thoroughly and in great detail observe every facial curve, every wrinkle and crease in its three-dimensional form. This spacial form shows itself differently during every angle of observation.

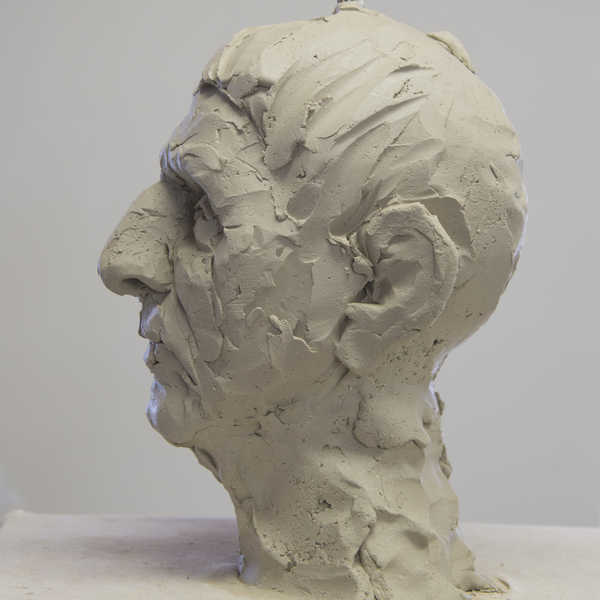

I take my time, concentrated and at length, to study my model's face from a distance, nearby and switching between proximity and distance. I use a piece of laminated chipboard covered with canvas and a metal bar mounted on top on which I apply the clay. In the beginning I try to grasp the contours and main form of the head as quickly as possible. I study and compare my sculpture with my model and try to get the big picture. I do not work with details until a rough sketch is done. But I tend to work on the left hand side first since I am right-handed the model's left hand side is easier to reach.

20130821

Today we had a third session and I am practically done with my sketch. I have worked very fast. In the first hour I have made the rough form, in the second hour I worked on the jawbones, the eyes and ears and in the third I started to fill in the details. I have worked less then three hours on this sketch, but I should have stopped earlier. I could have worked longer as well, but it wouldn't have become better. After half an hour I noticed that I lost concentration and that I was sort of done with this sketch, a feeling that I ignored—as I more often ignore my gut feeling. Since my model sat in front of me, I obviously at least had to pretend that it took more time than it did to make this portrait. I was ashamed that I went so fast. At the same time it is apparent that a lot of things are not done yet, like the right eye, the eye sockets and the right part of the chin.

What I did afterwards did not benefit my sculpture. I lost my open attitude, became self-aware and lost flow. I started to botch up. The additions I made, led my piece away from what I had in mind: making a sketch. I started to fill in things that were meant to be rough and sketchy, added details and finish. As a matter of habit I proceeded to the next stage, I noticed it, hesitated, but went on anyway.

20130828

This week Börje is unable to come, next week we will continue. That gives me the opportunity to have a close look at my sketch and work on this text. I haven't been so frequently in my studio the last half year. I worked on various projects concerning house and garden that consumed a lot of time. Biggest project of the year was casting a new concrete floor in a part of the studio that we call summer studio. Besides that we had a lot of guests and I worked part-time as a photographer. All in all, not much has happened in the studio and that makes me nervous: What is going on? Why am I not here? Do I try to escape? Is my artistic practice over?

- - - -

How is my sculpture? What is the difference between a 'finished' portrait and this 'sketch'?

I haven't seen my piece in a week and I want to be as receptive to it as possible. I don't look at it while unwrapping. I let it be. It is there, but I turn my back on it. I want to confront myself, as if I am seeing it for the first time. This is what I sometimes do, even while working: I'll turn my back on my sculpture, walk away and do something else, I don't look before I have some mental distance and then I cast a glance. I want to catch its gestalt, its epiphany. Once I have seen it passingly, I scrutinise my piece. When I study the details, I see what is not finished. It's unrefined condition doesn't disturb me as long as I keep distance. If I get closer, I want to change things. Especially the right side of the chin, the eye sockets and right eye need to be reworked, hair ought to be more specified. But I am actually quite pleased with how much I have done in a very short time. It is fairly good, if you consider mimesis as a legitimate principle. Despite my long absence from the studio, modelling is still in my fingers.

As I mentioned in the introduction, in my portrait series I don't want to position myself in between my sculptures and the spectator by adding a specific personal touch or style that draws attention to itself, like some sculptors who leave their fingerprints on their wax models as a prove of their artistry. But I don't want to make impersonal works either, I just want the focus on the content matter, on the story behind and not on the formal aspects, nor on its expressionistic qualities—even though I realise that these formal aspects dictate how the works are read.

With this portrait of Börje Lindberg however–as in all 'real' portraits –I don't have an underlying story. It is a portrait an sich, separated from the narrative portraits that I am used to making and for that reason I ought to have some chance for freestyle and experiment, to loosen up in a way I do not permit myself otherwise.

I call this sculpture a sketch since it will not be a final product but an intermediate for a sculpture in wood. But what is the difference between this 'sketch' and the sculptures I am used to making?

I rarely sketch, I don't use sketches for idea development or finding form for my sculptures, just occasionally I use sketches to see if an idea holds. My idea development takes place on a more linguistic level and is based on an interest, an intuition or an emotion that is evoked by a certain theme and often triggered by a picture or a text or a combination of the latter two that I find catching. I twist and turn this idea in my head, until I'm convinced that it holds, after which I carry it out. This makes my sculptural work conceptual by nature. In comparison my drawings come about in a more intuitive knowing of what has to happen next. Both methods share way that the knowing of what I want comes to me in an instance.

At art school I learned a working method of seeking form and a gradual development of this form through sketching in justifiable steps, a method that in my opinion belongs to design more than to art. Even though I know one can design a sculpture, to me it feels awkward, as if the work is detached from an inner vision and lacks deeper grounds, as if form rules over content. I realise that this idea is one of my idiosyncrasies, but this method has never appealed to me. I don't care about form for forms sake, even though form is very significant, it is subordinate to content matter.

As I see around me in presentations of contemporary art, I think it has become fashionable to make work that is objectified and 'designed', to make work that seems to be accountable and can be articulated in spoken language. These works often feel to me like a distant kind of works, works that can be read rationally, but are detached from the things that I seek in art: the personal, the emotional and the intuition. I have always thought that art has to come from within, that it is something you cannot design or think out, that art is given.

Art is a natural given instance that reveals itself.

Art has to come from inspiration, says Agnes Martin, "I don't have any ideas myself. I have a vacant mind, in order to do exactly what the inspiration calls for." (Agnes Martin in an interview with Chuck Smith and Sono Kuwayama) And this is exactly how I feel it: inspiration comes and goes, you can invite it, but not force it to come in—and moreover, you can't design it.

The closest I get to making what one could call a sketch is when I permit myself more freedom in interpreting my source material. But even then I don't sketch to find form, since I know where to go: I want to get close to the pictures I work with. In sculpture my artistic strategy is conceptual, my tactic is mimesis.

- - - - - - -

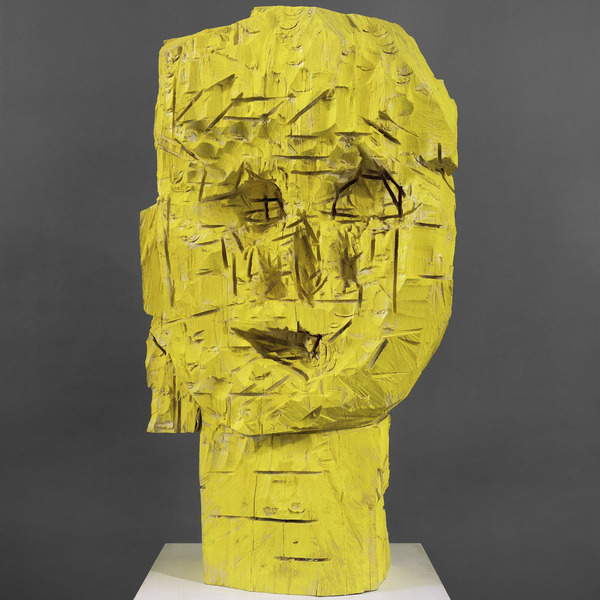

So what is the sketchiness of the sketch I make? I believe it lays in the details, in the unfinished form, in ragged edges, scruffy details and swabs of clay that are not yet in place. Compare with Georg Baselitz, he works on ragged edges, that's his specialty. For example his "Woman of Dresden", a series from 1990, the huge heads are coarsely cut with a chainsaw out of big logs of wood and painted in monochrome yellow (picture). Baselitz seems to be self-confident in what he does. Look at the eyes: they are positioned with only a few gestures. Expression is for him of greater importance than form, he doesn't care about details and that is effective: his sculptures are very present. In these works Baselitz shows that he is a man who doesn't hesitate handling the most masculine of all saws, the chainsaw. He is a show-off. I am more cautious and careful. I work extensively with the details and I want to finish the form as I find it difficult to let go. But I am not embellishing my work. I am more interested in work that is slightly unsettling than in idealising human existence–I don't make work to please. It would be interesting to see what happens if I pass over this finishing. In this sketch I will change elements that are not correct, but I will try to leave it in a crude stage. More Baselitz, less prudent.

The freedom I give myself in my work usually lies in the choice for a specific way of executing my piece, in the freedom of a more or less strict interpretation of my source material and in the degree of realism that I apply. However, in deviating from realism I never go as far as Baselitz; I don't experience that as free choice, but attributable to character.

20130903

Today we had our fourth session. During posing for Börje I thought of a way to change my strategy temporarily: I could make a series of introspective (self)-portraits. Portraits not based on mimesis with one or more pictures as a starting point, but made by heart.

I am interested in a working method as I have had with my drawings, where the possible outcome is more open and the interpretation more diffuse.

Of course I am not at all finished with the renewal of my process after only four sessions with Börje. I am not even sure what to expect of this renewal. Will I recognise it when it comes?

20130927

I am completing my portrait and I take away some of the ragged edges, so that the face appears to be more finished. But I am only taking away what disturbs me; I want to maintain its sketchiness. Börje has also finished his portrait so we are ready for the next phase. The way I am used to working with clay is so much incorporated in my system, that I find it very hard to leave my sketch in this unrefined and unfinished stage. Börje has toiled and sweated, he has overcome his fear and he felt more and more positive about his portrait. If I compare our works, I can say that I am stricter in my conception about form and mimesis as Börje put more emphasis on his inner vision.

page 1: Introduction

page 2: Meeting with Börje Lindberg

page 3: Intermezzo

page 4: Back to my project

page 5: Conclusion and References

The eyes and eybrowes

The right eye has not yet a good round form and is closed too much. The eyebrowses and sockets need to be more specified, as the pockets under the eyes. Good is that the eyes seem to see, despite that their lack of detail.

Detail

There is no clear distinction between the eye browes, the underlaying sockets and wrinkels in the skin.