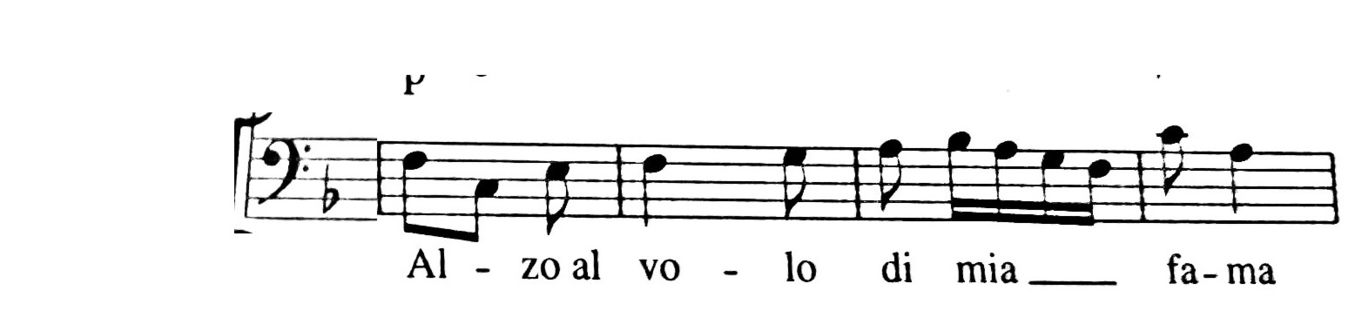

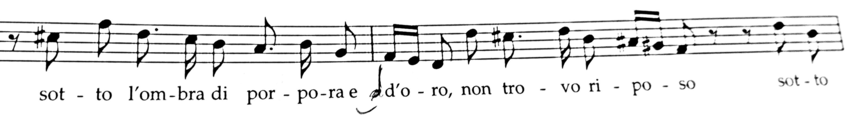

Figure 2. Fragments of “Empio, pero farti guerra” from Tamerlano (HWV 18)

On the other hand, the role of Grimoaldo (Rodelinda) presents coloratura moments written in a higher region of the voice than Bajazete. However, the range does not reach the extreme high notes, common on the tenor roles of the 19th century.

Even when Händel wrote the two roles (Bajazete and Grimoaldo) for the same tenor (Borosini), the arias of both parts do not follow strictly the same patterns in terms of vocal range or character of the music. Despite using the conventional elements of the Italian operatic style in his compositions, namely: trills, coloratura, long phrases…, “the aria was [for Händel] the form through which dramatic characters were portrayed, in their varying mood and reactions to particular situations”[2]. His interest in the voice acting as a vehicle for the drama and embodying the emotions of the role, brought him to compose in a way where he not only thought about the singer or whom he had to write, but also made him consider the dramatic action as well. This might be the reason why Celletti writes that singers from that time preferred the virtuoso formulas of Giovanni Bononcini and Hasse. Both composers wrote regularly using common musical patterns developed during the baroque opera and well-known by all singers. Händel, on the other hand, composed often unexpected sequences that stepped out from the regular opera tradition and that were less internalised by the performers. According to Burrows, “It may be that this was the first breach […] between the search for expression and the search for virtuosity”[3]. This quote however underscores why it is necessary to come back to ideas expressed by Rossini in his letter to Fillippi (which were mentioned in the first chapter of this paper). In this letter Rossini claimed that “Italian musical art (especially the vocal aspect) is entirely ‘ideal and expressive’ and never imitative”. In view of this, Händel, though to a lesser extent, shared with Rossini the idea of the voice acting as a vehicle for the emotions, one which did not require the pure need of imitation.

The tenor roles written by Händel were in general conceived for a baritone-type of voice (like Borosini). In that sense, the range of the parts rarely goes above A4 (e.g. only in a few passages does this occur). Furthermore, and as it can be appreciated in the examples given above, the coloratura moments are normally composed in the middle or low region of the voice, in some of the cases reaching G4 and A4 but never starting in this register. Probably Händel wanted to avoid that the more difficult passages were located on the sensitive parts of the voice (like at the break of different vocal registers). This concern can be observed as well in Rossini’s work, where “the design of the pieces […] ensure that some virtuoso passages or ‘agitated style’ explosions do not fall on an awkward section of the voice, such as notes on the passaggio”[4]. This pattern is present even in Rodrigo, Händel’s first Italian opera (1707), where even when the style of the tenor role (Giuliano) is closer to our actual leggero tenor, the vocal lines with coloratura still follow the same principle above described.

However, there is a role that steps out from this tendency: Tiridate, one of the big tenor characters written by Händel, and the evil emperor of the opera Radamisto (1720). For the first version of this opera, premiered in April of 1720, the German composer wrote the part for the tenor Alexander Gordon. The role, written in a higher tessitura than other Händel creations, is full of lines with coloratura on and over the passagio part of the voice (even long sustained A4). This breaks with the tendency usually respected by Händel of writing lines that help the singer to face the more challenging musical moments. One clear example of this difference of conception between Tiridate and other Händel parts can be found in the first aria of the character: “Straggi, morti sangue ed armi”. This aria was first written in the key of C-Major for the above mentioned opera Rodrigo (1707). However, in Radamisto, we find the same aria (with some small variations) one tone higher, D-Major. In Rodrigo, the aria is accompanied by an oboe, while in Radamisto, the solo instrument is a trumpet (always tuned at that time in D-Major). It is not possible to explain exactly why Händel decided to write the part of Tiridate under that characteristics. It could be that he used a very low diapason/tuning, or that maybe Alexander Gordon was able to sustain his chest voice register until a higher range than other singers. In any case, maybe because of the difficulty of the part, or perhaps because of the beginning of some conventions in the opera style which assumed that a villain should be performed by a low voice, or possibly due to the limitation of the singers Händel was working with, the reality was that in a period of some months, the whole tenor part disappeared from Radamisto. Morever, the role of Tiridate was rewritten in a second edition and was subsequently transposed for the voice of baritone.

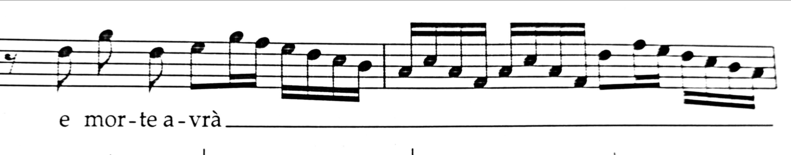

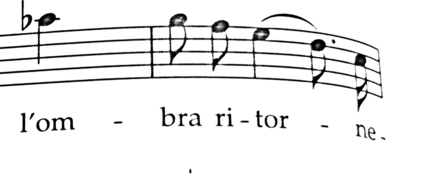

Figure 3: Fragmets of “Tuo druo é mio rivale” from Rodelinda (HWV 19)

Other parts of the same role show a less heroic character, more lyrical, or even closer to the tenore leggero.

THE TENOR VOICE IN HÄNDEL OPERAS

As it was already described in the first chapter, it is not possible to define exactly which music belongs to the bel canto tradition and which does not. However, following the conclusions pointed out in the previous part of this text, it is possible to at least analyse some characteristics of Händel’s compositions in order to identify key elements that will help us to classify him as a bel canto composer. Moreover, when we recognize such characteristic, then we will also have reasons to justify why the music of Händel should be performed according to the ideas and ways of the bel canto, specifically as they were discussed in the second chapter. Following this, and due to the focus given to the tenor voice in this research, I consider it necessary to first discuss the way the tenor voice appears in the operas of Händel.

It is however important to keep in mind that Händel lived in Italy during between 1706 and 1710, specifically in the cities of Florence and Rome. It was here where he learnt the national style of composition, which contributed to Händel being given the nickname ‘Il caro sassone’ (given to him in Italy), a name which suggests that he succeeded gloriously with respect to his absorption of this musical style. So deeply did Händel drink from the Italian style that, although he only composed two of his operas in the south-European country, his operatic work was immediately categorised as part of that tradition (and it remains this way even today). His operatic productions (after moving to England) also conserved the Italian influence and brought them to English audiences. Even his compositions written in English maintain the essence of the Italian characteristics he absorbed while being there.

Although this chapter seeks to focus on the tenor voice, it should be mentioned that Händel had a strong predilection for writing for soprano and male alto. It is well known too that the voice of castrato was a favourite of that time, and that the majority of the vocal-scenic repertoire was written for this voice. In that sense, the still undeveloped tenor voice ─ far away from the Rossinian tenor type ─ was unable to fight against the virtuosistic passages performed by the eunuchs, such as long coloratura phrases or easy changes of voice registers. The fact that approximately only half of the operas written by Händel have a tenor part in them furthermore confirms this idea. And the fact that only a few of these tenor roles plays a particular importance in servicing the plot of these operas further illustrates Händel’s preference for other vocal types. The next table shows the tenor roles that can be found in Händel’s operatic work.

|

Opera |

HWV |

Year |

Country of composition |

Language |

Tenor role |

|

Almira |

1 |

1705 |

Germany |

German |

Consalvo / Osman |

|

Rodrigo |

5 |

1707 |

Italy |

Italian |

Giuliano |

|

Rinaldo |

7a |

1711 |

England |

Italian |

Araldo |

|

Rinaldo |

7b |

1731 |

England |

Italian |

Goffredo |

|

Radamisto |

8a |

1720 |

England |

Italian |

Tiridate |

|

Flavio |

16 |

1723 |

England |

Italian |

Ugone |

|

Tamerlano |

18 |

1724 |

England |

Italian |

Bajazet |

|

Rodelinda |

19 |

1725 |

England |

Italian |

Grimoaldo |

|

Scipione |

20 |

1726 |

England |

Italian |

Lelio |

|

Alessandro |

21 |

1726 |

England |

Italian |

Leonato |

|

Lotario |

26 |

1729 |

England |

Italian |

Berengario |

|

Partenope |

27 |

1730 |

England |

Italian |

Emilio |

|

Poro |

28 |

1731 |

England |

Italian |

Alessandro |

|

Ezio |

29 |

1732 |

England |

Italian |

Massimo |

|

Sosarme |

30 |

1732 |

England |

Italian |

Haliate |

|

Oreste |

A11 |

1734 |

England |

Italian |

Pilade |

|

Ariodante |

33 |

1735 |

England |

Italian |

Lurcanio / Odoardo |

|

Alcina |

34 |

1735 |

England |

Italian |

Oronte |

|

Atalanta |

35 |

1736 |

England |

Italian |

Aminta |

|

Arminio |

36 |

1737 |

England |

Italian |

Varo |

|

Giustino |

37 |

1737 |

England |

Italian |

Vitaliano |

|

Fabio |

38 |

1737 |

England |

Italian |

Berenice |

The next quote by Celletti confirms the idea exposed above:

Nor did he have notable tenors –indeed often he had none at all- until 1721, when he engaged Francesco Borosini as Bajazete in Tamerlano. Borosini came from Vienna and was decidedly of the baritone types […]. In Händel his tessitura runs from g to e’, and the range from c to a’. Bajazete is, all in all, an epic-style personage and a noble father, and in some of the ‘scorn’ arias we find passages of ‘leaping’ syllabic singing and arpeggio-style vocalises characteristic of the heroic tenor up to the beginning of the 19th century […]. Still in robust singing with wide intervals we get the more typical arias sung by Grimoaldo in Rodelinda.[1]

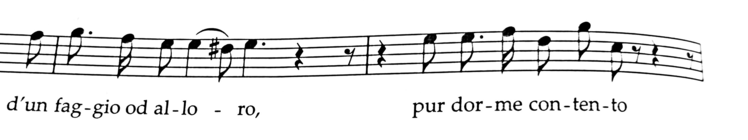

The nexts pictures ilustrate fragments taken from the operas Tamerlano and Rodelinda. All excerpts are written in G-clef:

As we can appreciate, the majority of the coloratura parts of the role of Bajezete (Tamerlano) are written mainly in the lower-medium region of the voice.

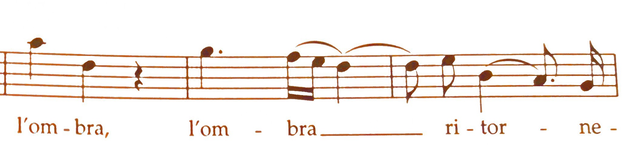

Figure 6: Excerpt from the aria "Alzo al volo di mia fama" from Radamisto HWV8b (baritone version)

Once more, the length and purpose of this research does not allow me enough time to analyse all the tenor roles written by Händel. However, it is possible to identify multiple musical examples that show how the German composer followed the precepts of the bel canto school, namely coloratura, messa di voce or mezza voce. Also visible is a certain tendency towards composing that treats the tenor voice in a related aesthetic to music written for castrato. The higher tessitura of the parts showed in later operas like the first version of Radamisto (1720) or in Ariodante (1735) and musical elements such as the more and more complex coloratura passages, likely signal a slow but significant evolution of the tenor vocal technique. With the abolition of castration in 1770 , the increased preference given to the ‘natural’ voice vis-à-vis Gluck and his revolution, and the fact that tenors were able to approach the level of virtuosity only previously found in castrati singing, contributed to the tenor voice becoming the most celebrated vocal-type of the Romantic bel canto. But not only that: the aforementioned prohibition of castration was a death blow for the interpretation of the baroque opera in general, and for Händel’s operatic music in particular. Consequently, Händel’s last opera, Deidamia (1741), had very little success.

It was only during the arrival of the 20th century when the revival of the historical informed movement revived interest in Händel’s repertoire. Furthermore, this recent period of music history coincides with the rise of countertenors — singers technically capable of ‘replacing’ the old castrati — and this helped enormously to allow the rediscovery of Händel. But, what happened to the other voice types and especially to the tenor roles from Händel’s time? As I discussed in the second chapter, vocal technique experienced a huge change after the second half of the 19th century. Additionally, the rediscovery and reinterpretation of old repertoire was made applying the technique used at the first half of the 20th century, and developed after Duprez’s revolution. There was no deep reflection about the ‘proper’ manner of singing Händel. The following recordings, with singers of the beginning of the 20th century performing Händel music, show a vocal technique that could be used for the interpretation of other type of repertoire (such as Verdi or Puccini).

Nellie Melba sings "sweet bird" from L'allegro, il Penseroso e il Moderato. Recording of 1908.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J4WdMVREnUE

Lucy Isabelle Marsh recorded in 1912 "I know that my redeemer liveth" from The Messiah.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7seMHI9mzQg

Enrico Caruso in a version of "Ombra mai fu", from the opera Xerxes, recorded in 1920.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4nQXd3OyEz0

Our modern singing technique, although a heritage of the bel canto style, is more related to the technique used by the masters from the beginning of the 20th century than one that would have been used in the 18th century. Even when nowadays there is a conscious effort towards the historical informed praxis, we, singers, tend to work more on adapting our modern technique to a supposed ideal of sound, as opposed to using the old manners and precepts of bel canto singing. In that sense, I decided to record two arias composed by Händel in order to evoke the vocal technique that, in my opinion, could have been used by the singers of the “Händelian” past. These recordings represent the practical goal of all the explanation given throughout the previous three chapters.