Embodied Memories was commissioned by the John Hansard Gallery. I was funded by Arts Council England to make a new piece of work that would commemorate the department store Tyrrell and Green. The new complex that would open in 2018 and house the John Hansard Gallery was to be built on the site of the department store, which had been a fixture of Southampton’s Above Bar Street from 1898 to 2000. In the accompanying publication to the exhibition, John Hansard Gallery Director Stephen Foster described the work:

The project began with sound recordings that were conducted to attain only a description of an object as it was remembered by the owner, which crucially includes gaps, uncertainties and forgotten details. These descriptions were used as the source, from which to have new garments and objects made. Some parts of the descriptions are incredibly vivid, though not necessarily accurate in terms of the material qualities. The inevitably patchy recollection, as well as the self-imposed reliance solely upon the description using unreliable language, is the crux of the project enquiry: a practical and tangible exploration into identity, memory and the (mis)communication of image. This practice of referencing pieces from the past resonates with the practices of couture, designers of couture garments continually refer to cultural and sartorial history, creating a space that simultaneously allows for the voice (and image) of ghosts of the past, whilst providing something new (Bancroft 2012: 89). The project emphasised the garments (some of them at the time of the project being undertaken no longer in material existence) seeking to erode the material status of the object by placing the emphasis of the study on the ‘affect’ of said objects (not frocks, but coats, lingerie, shoes, and jewellery) on the consciousness of the wearer, even years later.

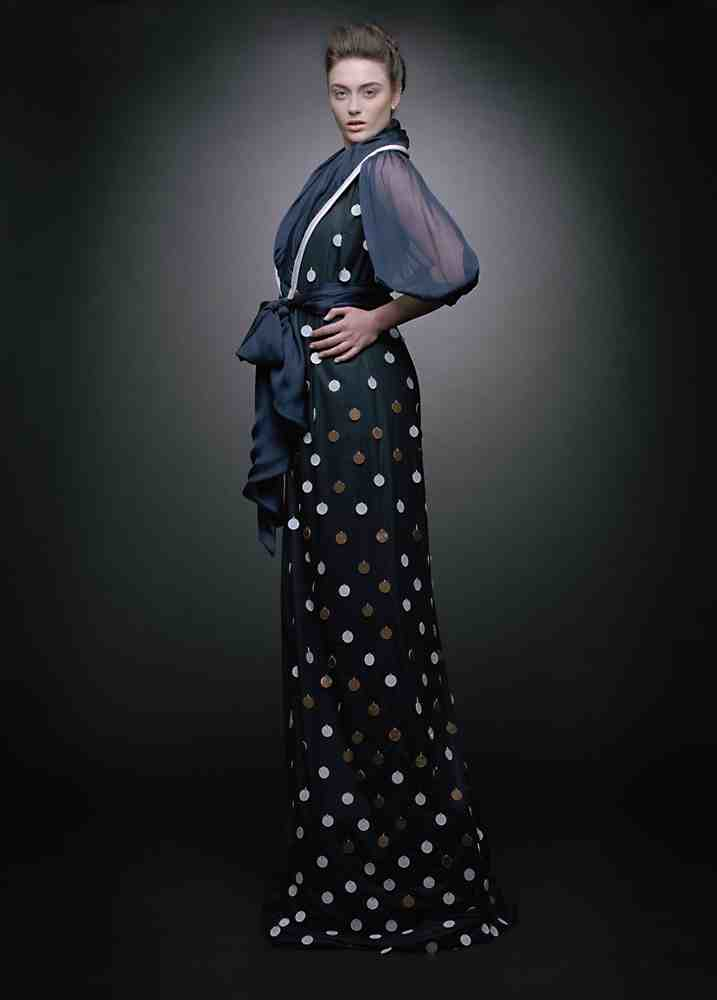

Having gathered around thirty audio descriptions, seven were chosen and through interpretation of the audio descriptions. I translated the spoken words into designs for new objects that attempted to embody the memory described in the audio, rather than achieve a historical representation. Based on my design and specification, and using materials that I sourced, I worked in collaboration with a garment technician, cobbler and jeweller to make new objects: Doreen’s Housecoat, Eva’s Raincoat, Cilla’s Cape with Red Hair and Jane’s Brooch are included in this exposition.

Audio Transcription:

The Summer housecoat (we got married in August) was such a super garment! It was floor-length, cotton, I think glazed cotton it was probably called, navy blue, with coin dots, white dots, white coin shapes all over it. Very shaped to the body, tied around the waist with a big sash, three quarter length sleeves that were gathered in and again a shawl collar and that used to feel lovely to wear.

In the description referenced in making the piece Cilla’s Cape with Red Hair, Cilla describes her dyed red hair as synonymous with the royal blue cape. In my interpretation of the cape, a long red wig was sewn into the hood so that in wearing the cape, the wig is also worn; the hair is an integral part of the cape. This decision to sew the wig into the hood was an attempt to conjoin the memory of the coat and the hair Cilla describes of herself at the time. “royal blue and white and bright red hair at the time, so that must have looked a bit gaudy, but hey!”

The body of verbal descriptions gathered was rich and varied. I found that the more passionate someone was about a garment or object, and its connection to an aspect of their identity or a time in their life they cherished, the more elaborate the description of the object tended to be. Eva, when describing her raincoat, is a wonderful example of this vibrant enthusiasm:

When Eva later mentioned the brand of her raincoat, Telemark, a brand known for skiwear this was a surprise. The jacket described in my mind, and that I later created through my interpretation of Eva’s description, did not have the functional qualities of a Telemark coat. Eva mentioned the brand as an indicator of quality; this is a quality I aimed to embody through attention to detail in creating the ‘stained glass’ quilting.

Cilla’s Cape with Red Hair, 2012

Blue wool cape, with white wool lining, white plastic buttons and red synthetic wig sewn into the hood.

Photography: Chris Overend

The moment of horror Jane describes as she gazes upon the brooch in the box, and tries to reconcile it with the chasm between her sense of self and what she feels the brooch represents, is both comic and horrifying. Jane’s horror at this moment of gazing upon the brooch, that was so far from what she deemed ‘her,’ is akin to a moment in Woolf’s short story The New Dress. Mabel Waring's experience of the yellow dress, that when being fitted in her own drawing-room felt so right for her, changes when she wears it out to a party, to the extent that she cannot contemplate looking in the mirror.

Eva’s Raincoat, 2012.

Nylon, wadding, wire, press studs, paper, balsa wood, spray paint. Photography: Chris Overend.

This project uncovered that clothing affects the wearer not just in the moment -when we feel its structure, its texture and its weight upon our body, shaping quite literally how we feel as a being within its boundaries - but also for decades afterwards. Ruggerone argues that within sociological and cultural studies research, the feelings that we experience ‘about and in’ (2016: 573) our clothes have been overlooked. She pays attention to the affective properties of clothing on, and with, bodies to create ‘becomings’, or transformative encounters. The emphasis is on feeling and emotions, in contrast to a reading of the body that is situated within the mind. Wacquant’s work in what he calls ‘carnal sociology’ also focuses on what happens when we consider ‘the sensate, suffering, skilled, sedimented and situated corporeal creature’ (Wacquant 2015: 2). Both Ruggerone and Wacquant focus on the moment of affect. Some of the participants, who described for me items they had worn and loved, were recalling garments they had worn twenty, thirty or, in the case of Doreen, approximately fifty years beforehand. Almost all of the participants expressed strong emotions towards the garments or items they described, and the emphasis within their recollection was often upon how the garment had felt and, in conjunction with that, how they saw themselves. Eva says ‘I thought I was the bees knees in it... I loved the colours, it actually suited me' (Anyan, 2012: 21).

This work explores how frock consciousness endures and effects not just the moment in the clothes, but a sense of who one is as a result of that moment. This is emphasised not just in the descriptions that are joyful, revelling in clothing that was adored but also in moments of despair. Jane’s description of a brooch gifted to her by her then-boyfriend, who she promptly broke up with, in part at the horror that he had misjudged her, in gifting her something so garish, captures that offence one feels when someone we believe should ‘know us’ makes a judgement that is at odds with our perception of self and how we believe we are communicating.

...it had a sort of African, it had a ruffs collar, and sort of African, um, like patchwork, all different colours, like a, a bit like a stained glass window kind of thing... it had sort of abstract flowers on the back and it had piping, black piping on it, crisscrossed and it came down in a 'v' a deep 'v' at the back, so you had all these lovely misty pinks and blues and pinks...

(Eva, 2012)

“Jennifer was interested in studying the relationship between place, clothing and identity through the creation of a new body of work in response to verbal descriptions of treasured Tyrrell and Green purchases of clothing, jewellery, and accessories, and in particular, the gaps and absences in those recollections. These descriptive rifts and the infinite possibilities for reinterpretation created, allowed Jennifer to explore the way personal identities are constructed and experienced through clothing and personal items [my italics].”

Whilst Mabel's upset is with herself, in feeling that she misjudged the dress, and how it would be read once situated in the social scene in Clarissa Dalloway’s home, Jane is upset by the realisation that her boyfriend does not understand who it is she really is: not the woman who would wear this brooch. Both Mabel and Jane demonstrate the extreme emotional reaction that can be provoked by clothes, or personal items that feel wrong, being ascribed to us by ourselves or others. Mabel describes this visceral feeling: “flies trying to hoist themselves out of something, or into something, meagre, insignificant, toiling flies”. (2015: 2) This is a powerful expression because it describes the experience of being both disadvantaged, and being physically dragged down, by a dress that is not reflective of our interior self-image.

“I opened this box and nestled on the dark velvet interior was this kind of carbuncle of a brooch. It was so not to my taste in so many ways that I almost couldn’t feign pleasure at receiving it… it was so not lovely in so many ways… it was quite violently coloured, the stones were quite garish and dare I say it, looked cheap… it looked like something that maybe my aged aunts would wear and my aged aunts aren’t dowagers, do you know what I mean?” (Jane, 2012)