Levantis Museum Old Mapx

I WANT MY CYPRUS TO. Ledra Palace Border Crossing, 2016x.

Description of the East x

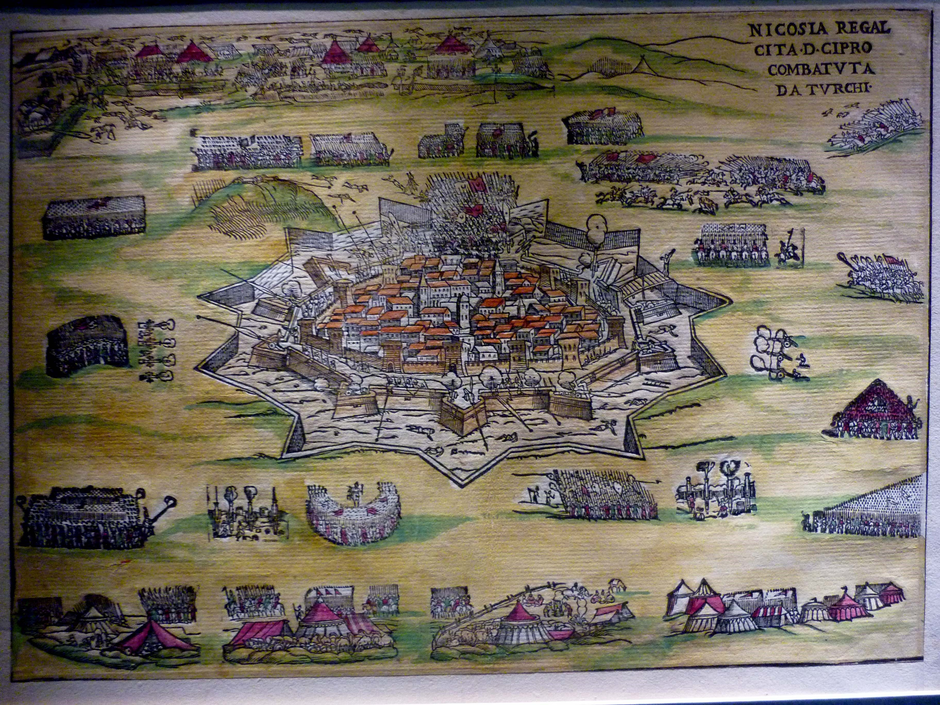

'Green Line', 'Buffer Zone', 'Attila Line', 'Dead Zone', 'Zone of Shame’[1] there are many names for the ragged line of the UN-brokered demilitarised zone, which for just over forty years – since 1974 – has cut Cyprus into two distinct national entities: the Republic of Cyprus and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. The line runs west to east or east to west across the whole Island and marks the limit of the Turkish army’s invasion during July and August 1974. It meanders in relation to the landscape, and expands and contracts from four or five kilometres in width to a matter of a few metres. At or near its centre stands the Island’s capital city, Nicosia. The City has a long history that reflects all the periods of human occupation and trade found on the Island, whether that of the Neolithic, the Antique, Byzantine, Ottoman, Colonial or the modern periods. The fortified City centre, now cut in half by the line of the demilitarised zone,[2] stands, isolated by its ramparts, from the two disconnected modern cities that have grown northwards and southwards from its walls. Having withstood a series of historical invasions, in the 1970s the fortress was bifurcated and the two constructs of Lefkosia and Lefkosha (transliterations of the Greek and Turkish, respectively) emerged.

[1] Papadakis, Yiannis. Echoes from the Dead Zone: Across the Cyprus Divide, London: I.B. Tauris, 2005, 83.

[2] ‘A line ran through walled Nicosia in medieval maps; another through contemporary ones. The two lines were almost identical, dividing the city along an east-west axis. The line crossing the medieval city was a river. Later through human effort it became a long bridge; later still, through more human toil, it was turned into a chasm, a dangerous no man’s land.’ Papadakis, Yiannis. Echoes from the Dead Zone,2005, 168.

Flute-maker, The Municipal Market (Bandabulya), Lefkosha x

Cafe at Home for Cooperationx

Intercommunal and cross-border walkx

In the tired confusion of small streets behind the Lusignan Cathedral of St. Sophia, now the Selimiye Cami (Mosque), is the small shop window of an elderly Turkish photographer’s studio. Among the chaos of photographs of Northern Cypriot politicians – Rauf Denktash key among them – actors, singers, and other memorabilia, there are still the curious celebratory, but faded, portraits of young Turkish soldiers. The now ageing and fading images suspend their youthful faces in time. Classically posed studio portraits, each individual is superimposed onto the outline of Cyprus – the ’babyland’ to the Turkish ‘motherland’.[1]

[1] Papadakis, Yiannis, Echoes from the Dead Zone, London & New York: IB Tauris, 2005, 21.

Promotional image of the ruins at Agios Sozomenos, Larnaca Airport x

Both sides of the line are buffered from the rest of the two Cities by an uneasy and shadowy terrain of partial urban neglect;[1] areas that Christopher Hitchens collectively defined as early as 1984 as ‘one of the world’s political slums’.[2] All streets and roads were cut at the line, even the main shopping street of Southern Lefkosia, Ledras Street. When the street was fully closed, the Greek-Cypriot barricade was the South’s only sanctioned up-close viewing point into the Dead Zone/Buffer Zone: it comprised a guard post and a viewing platform that hovered between the theatrical and the threatening. Peering, as one could, through the one gun-slot, just four metres above ground level, each viewer became witness to a dissolute and maudlin space. The last strip of the old main shopping street of Nicosia – its life truncated and overgrown – was deteriorating into a rusted barbed wire and cement-filled oil drum-littered world. It had become a voided space that Hitchens summed up in the following terms: ‘only the weeds and nettles justify [its] designation [as a part of the] ‘Green Line’’. [3]

[1] Major works are now underway on both sides of the line to rejuvenate these neglected areas.

[2] Hitchens, Christopher, Hostage to History: Cyprus from the Ottomans to Kissinger, London: Verso, 1977, 20.

[3] Hitchens, Hostage to History, 1977, 20.

Walking with a member of the Nicosia Master Plan we were told that in the wake of the generations of troubles, just across the water in Lebanon, Israel, Palestine and Syria, the Omeriye Mosque Area had become host to many immigrants from those countries. According to City records the character of the area has changed, and some tensions have lingered. The mosque, originally the fourteenth century church of St. Mary, was part destroyed and later dedicated to the Muslim Prophet Omer after the Ottoman invasion in 1570. Now, once again, it seems it has a congregation.

Night time just within the Buffer Zone in the Kaimakli suburb of Nicosia with our architect guide and his small Cyprus Poodle straining at the leash ... silent earth, silent dwellings.

We retreated to the security of our friend’s home. It is a place with fluid walls and deep pink Bougainvillea waterfalls in each courtyard: private and public space intermingling, and permeating each other.

A student project at ARC, the University of Nicosia and a morning’s discussion with students has aimed us to this place: not so remote, but drifting further and further away in terms of memory – and history. Agios Sozomenos under limestone cliffs, was once chosen by an ascetic monk for his otherworldly retreat. It then became a place of pilgrimage, a village; and, since 1964, a dissolving ruin.

The remains of the village of Agios Sozomenos lie close to Dali, Potamia and to the UN de-militarised Buffer Zone. Due to the village’s abandonment in 1963, and its subsequent degradation over time, many traces have been lost or are only just visible to the discerning eye[1], including the lookout posts that mark the line of the Buffer Zone. The landscape surrounding the village was and remains a very fertile area – a place of barley – but one that requires irrigation.

[1] See Tsiouti, Andri, Agios Sozomenos: Landscape as a Palimpsest, National Technical University of Athens, 2014.

The need for water to nourish the crops was a paramount concern for those living off or working the land. In his account of the inter-communal violence in 1964 Martin Packard[1] wrote directly of the chaos that seemed to surround his Land Rover as he travelled to, from and between communities in the Agios Sozomenos, Potamia and Dali area. In his book, Getting It Wrong: Fragments from a Cyprus Diary 1964 (2008), Packard devotes an eight-page chapter to the occurrences in February 1964 that led to the Turkish Cypriot flight from Agios Sozomenos. Packard states:

Few aspects of Cypriot life demanded so much mediating attention as the island’s antiquated water system. Water for agricultural use was usually delivered through open conduits controlled by a variety of sluices whose operation was the responsibility of a special village constable [...] Inevitably there were frequent disputes. In areas where there was hostility or a stand-off between the two communities, rows over water sometimes triggered a gunfight.

The attack on the village of Agios Sozomenos, although brief, left in its wake a number of dead on both sides and, in Packard’s terms, proved to be “a grim milestone on the road to ethnic separation in Cyprus.”[2]

[1] Packard’s life was one typified by a mix of outsider-insider stages: the son of a country parson, he served as a pilot in the American air-force, and in 1963 he was appointed to NATO as an intelligence staff officer in Malta and then to the staff of General Peter Young in Cyprus. (His account of the troubles in Cyprus derives from his period of service in Cyprus.) Post his Cyprus experiences he seems to have fallen foul of the Foreign Office and avoided court-martial through retirement. His biographer summing up Packard’s history as ‘one of principled motivation running into the buffers of virulent opposition from those who wanted to manipulate events for their own interests.’

[2] Packard, Martin. Getting It Wrong: Fragments from a Cyprus Diary 1964, Milton Keynes: Author House, 2008, 155.

Agios Sozmenos, like all villages, constitutes a palimpsest, and a series of fragmentary remains of different historical periods. These range from the Pleistocene – geological formations of the hills – the fossil remains through to archaeological findings and sites that date to the Bronze Age, the Byzantine, the Medieval and Ottoman periods. According to Eratosthenes of Cyrene (3rd Century. BCE), the area around Agios Sozomenos and the Mesaoria plain had once been covered by dense forest, that the trees had been felled for ship building and for charcoal necessary to the process of smelting copper, found in the earth: the landscape becoming collateral. By the 12th Century the place became the sanctuary and retreat chosen by the Palestinian hermit and saint, Saint Saviour (Agios Sozomenos). Little is known of his origins or life. He may have been born and raised in Palestine or Jordan, but after the Arab invasion he retreated to Cyprus. His hagiography, brief though it is, paints his as a peaceful desert loving individual, much in the spirit of the Egyptian desert fathers. Having travelled across the Mediterranean he came to the seclusion of Agios Sozomenos where he dug and carved a hermitage-cave in one of the sandy escarpments of the area, which is still visited today.

Place Of Barley, Agios Sozomenos. Discussion with Nikos Philippou. 2018. x

The abandoned, and now ruined, inter-communal village of Agios Sozomenos lies in what is the Republic of Cyprus, just a few kilometers south of the UN brokered demilitarized Buffer Zone and some 30 kilometers east of the City of Nicosia. The village is almost completely derelict, most of the adobe structures have washed down into the soil, and just a few substantial remnants of buildings remain. These being the former Turkish Cypriot School Building built on a knoll to the north of the village, the centrally located but only half-built late-medieval St. Mamas Latin Church, and the small stone structure of St George’s Byzantine church.

Buildings without walls litter the landscape: their windows and doors empty slots; the vestiges of walls eroding silently back into the earth. The decaying ruins of the village now lie within a semi-protected realm and ecological site designated within the context of Natura 2000. Like all Natura 2000 sites, Agios Sozomenos, is not a nature reserve in the strict sense of the term, but one in which the conservation of land, habitat and animal species is viewed in a way that also includes appropriate human activity and working practices (those that are both ecological and sustainable).

Sitting here at the Patek Café, right by the Venetian City walls, thinking of the caged birds at the café’s doorway, we realized we had been here before: when Beirut had come under attack and refugee ships were crossing the sea towards the relative safety of Cyprus. The City walls fifteen-metres high, whilst not blocking the sunlight, obscured any view of the harbour, the disembarking refugee ships and the open sea that lay between us and the Lebanon. ...

On the demarcation line of the Buffer Zone, where the public beach meets the military limit, and where the sand meets the sea, an unidentified bird perched. With a kingfisher-like shape and bill, but predominantly black, with a white back-stripe, it may have been a Smyrna Kingfisher (Halcyon smyrnensis smyrnensis) – “a very rare vagrant” – but could also have been a Black Tern (Chlidonias nigra nigra); another migrant.

CCFT at Famagustax

Our seat companion on this flight turned out to be a middle-aged Greek Cypriot man returning home to the Larnaca area after visiting his children in London. He was originally from Famagusta (Gazimagusa), but post the Turkish Invasion of 1974 his family – he was just a child at the time – were among those displaced/relocated to the South. He later moved to London, where he worked as a musician playing Latin American dance music. He had children (who have stayed in London), while he and his wife have returned home: not to Famagusta but to Larnaca. When he can, he travels back to London. His heart is continually split...

A plain clothed Turkish Cypriot policeman – our temporary shadow on the beach at Varosha, wearing immaculate black sports clothes and white trainers – leaned in to listen to our conversation. Apparently observing that as international visitors we posed no threat, he disappeared as discreetly as he had appeared.

Towards the end of his short life the poet-wanderer, Arthur Rimbaud, came to Larnaca, “...not knowing in which direction [he’d] be made to turn.”[1] Briefly, he found contracting work in an area he described as a desert. He wrote no poems, that period was gone, but just a few letters and then he moved on to Aden to work as an agent for a coffee merchant.

[1] Rimbaud, Arthur. Selected Poems and Letters, Jeremy Harding & John Sturrock (eds/trans), London: Penguin, 2004, 270.