6-Dynamics

As explained in the first chapter, the variety of dynamics appears at the beginning of the 19th century as a fundamental tool to avoid monotony in music. Lefèvre defines dynamics, a nuance in the sound, as follows:

"To nuance a sound is to give it more or less strength at the beginning or the end, depending on the genre."1

Therefore, the play of dynamics can be summarized in these main ideas: play more or less loudly, increase or decrease the sound. In the Méthode de violon (1803), first violin method of the conservatory, Baillot, Rode and Kreutzer give details about these different possibilities. These principles can be applied to a single note, to several, or even to a whole phrase.2These same principles are retained in Baillot's second method,3 L'Art du Violon (1834). Garaudé, in his Méthode complète de chant (c.1825), refers to these different principles by speaking of "various effects or inflections, to which a sustained sound or a musical phrase may be susceptible.”4 Frédéric Berr also details them in his Traité describing different ways of conducting the sound.5

We can distinguish as follows:

- The sustained sounds forte or piano. The dynamic must be equal from the beginning to the end of the note or phrase. Although Berr explains in great detail how to play the excerpt in a perfectly linear and homogeneous way, it is very likely that in practice this case is very rare. Indeed, as will be explained later, giving a shape to each note and each phrase should always be the priority.

-The sounds played Crescendo. The intensity must increase gradually.

-The sounds played Decrescendo.

-The Son filé. This concept is developed in the next part of this chapter.

These principles form the basis of the way in which the dynamics are used.

As explained in the first chapter, dynamics are an important part of the accent material, which is intrinsically linked to the character. Therefore, the different dynamics are more or less pronounced depending on the character of the passage. This is explained very clearly by Garaudé:

"The dynamics indicated under the various musical phrases must have a different character, execution and colour in a noble and severe adagio, in a brilliant rondo, in a cavatine with a soft style..."6

Accents particuliers (specific accents)

As explained in the first chapter, Frédéric Berr writes about different accent particuliers, in other words accents that apply to only one or a few notes. A very clear preference on how to make accented notes is stated: it is the use of a dynamic that is most suitable.

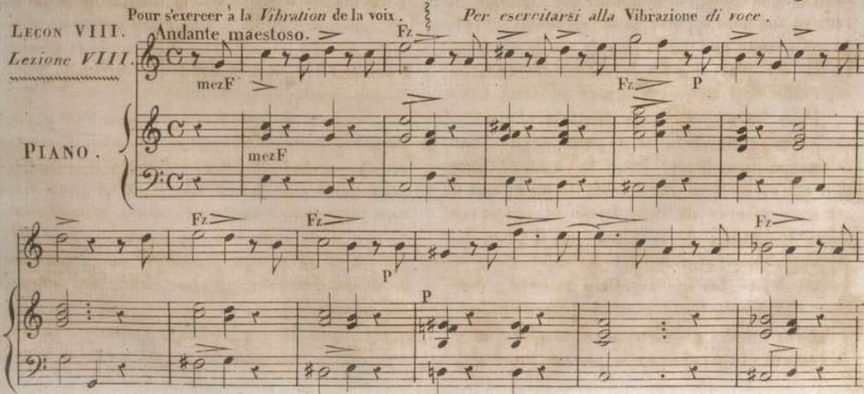

This dynamic to accentuate a specific note is called Vibration du son (Vibration of the sound) by Frédéric Berr,7who may have been influenced by the concept of Vibration de la voix (Vibration of the voice) developed by Garaudé.8

"We call Vibration du son a way of attacking it with strength and confidence, and letting it gradually weaken until it ends very softly."9

Thus, it is a question of playing the accentuated notes decrescendo. In the examples, this effect is therefore indicated by the sign >. The Vibration can be executed on several notes.10

According to Garaudé, it is mainly found on the tonic accent of words, as well as on the strong beats and appoggiatura.11His explanations about syncopated notes and sons coupés (shortened sounds) suggest that he uses the same dynamic on these specific accents. Frédéric Berr, apart from the tonic accent linked to the text which does not concern instrumental music, also speaks of these elements and adds triplets, leading tones, accidentals and notes jetées.12

The execution of the appoggiaturas was detailed in the previous chapter of this research. It is interesting to explore in detail the other specific accents and to try to give a broader perspective on them through the writings of other authors.

Crescendo / Decrescendo: on one note and on several notes

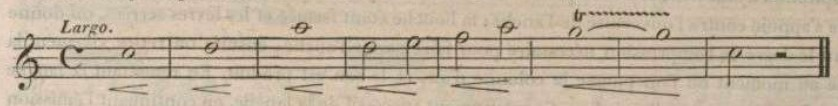

Sons filés, Messa di Voce

In Mengozzi's Méthode de chant du conservatoire (1804), the exercise of sons filés appears to be essential from the very beginning of the studies. The son filé begins piano, and has to increase to the forte, which is at half the value of the note. On the second part of the note, the sound has to decrease until the end. The crescendo and decrescendo must be continuous and progressive. He specifies that this way of executing a sound corresponds to what is called in Italian Messa di Voce.13

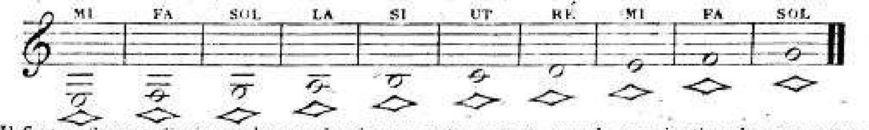

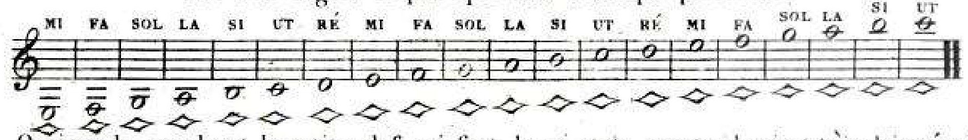

One of the exercises proposed to the singers is to perform sons filés lasting 20 seconds on each note of the scale. An inhalation separates each note. It is interesting to notice that Lefèvre proposes the same exercise for beginners, starting with the notes of the Chalumeau register. The range of the scale should increase gradually, as the student progresses.14

This exercise on sons filés obviously aims to acquire the habit of playing crescendo and decrescendo but also to develop the quality of the sound. For example, Wünderlich and Hugot affirm in the flute method that: "The only way to acquire a beautiful sound [...] is to execute sons filés."15

In the 1830s, this exercise is still widespread. It is found, for example, in Dauprat's horn method.16

Frédéric Berr states:

"The scales filés are the most useful exercise to obtain a beautiful sound, to form the embouchure, to give hold and width in playing."17

The importance of the concept of sons filés in all the methods studied demonstrates the importance for the performer of knowing how to give a shape to each note and how to keep them alive. Thus, Mengozzi writes that a good singer will always perform, "all proportions kept", Sons filés on each of the notes he has to sing, especially on the long ones.18 As late as 1836, Frédéric Berr writes that:

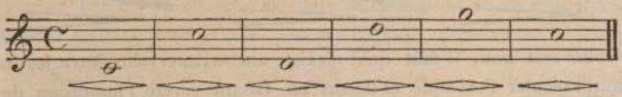

"It is still a rule without exception that all the long notes must be filé, even though the sign <> would not indicate it. Often even a quarter note must be filé; the expression is less sensitive, but it must still exist."19

This idea that each note must be filé echoes the words of Quantz who wrote in 1752:

"Each note, whether it is a quarter note, eighth-note, or sixteenth note, should have its own piano and forte, to the extent that the time permits."20

The need to find the right proportion in the application of this principle appears fundamental. This proportion depends on the length of the note but also on the character and general dynamic of the musical passage. This last point will be discussed in the last part of this chapter. Moreover, despite this "rule without exception", priority can also be given to a more direct attack as described by Frédéric Berr and Garaudé. (see part “specific accent” of this chapter).

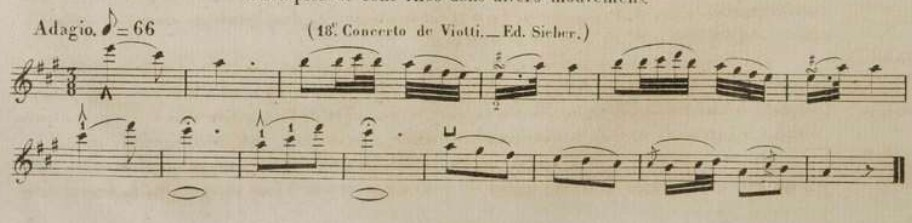

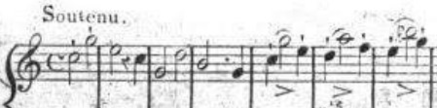

Thus, obviously, this principle also has its own nuances. The son filé appears as an expressive resource to be used according to the character of the music and the taste of the performer. This resource seems particularly suitable for the performance of an Adagio. At the beginning of the 19th century, Mengozzi wrote that in order to sing the Cantabile, which corresponds to the Adagio of instrumental music, the singer must perfectly master the art of executing the Son filé. It is according to him mainly in this character that the opportunities to use this dynamic are found.21 Ozi, Hugot and Wünderlich also give an important place to the son filé in their explanations of how to play the Adagio.22 23In the later methods, this tendency is still present. Like Mengozzi, Garaudé sees the mastery of sons filés as an indispensable quality for singing the Cantabile properly.24

Baillot, in his second method, shows nevertheless through several examples that the use of son filé can be used in different kind of movements.25

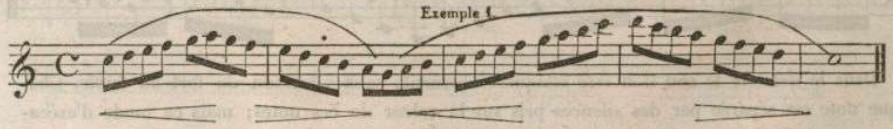

Crescendo and decrescendo according to the melodic line

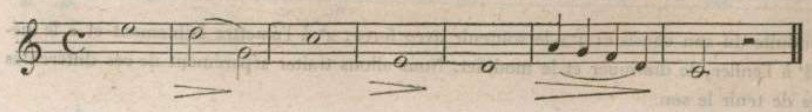

Like the sons filés, the general principle of playing crescendo an ascending melodic line and decrescendo a descending melodic line is explicit in all the methods studied. Mengozzi explains that:

"It is a general and constant rule when singing, which teaches that of two sounds, the higher one must be articulated with more force than the lower one: so that as the sounds go up their force increases, and as they go down their force decreases."26

This rule of singing also applies to instrumental music. Mengozzi explains that this principle helps to compensate for the weakness of the voice, which increases when it goes higher in pitch. By increasing the intensity of the sound, a good balance between low and high notes is maintained.27 Baillot justifies this law in a more poetic way. For him, music goes towards the high notes because the strength of feeling increases. It is therefore natural to increase the intensity of the sound.28

Examples of this principle can be found in Lefèvre's method.29

Frédéric Berr suggests that this principle is nothing else than an application of the concept of son filé to several notes or an entire phrase, "as if these notes and the phrase were a single note filée."30 This idea is also found in Garaudé's method of singing.31

Back to Table of contents

Strong beats

The strong beats of the bar are described as "more sensitive, more marked" by Berr32and having a "character [which] requires a more pronounced colour" by Garaudé.33

At the beginning of the 19th century, if the concept of hierarchy within the bar is not explained in details in the instrumental methods used for study at the Paris Conservatory, it is presented as an elementary principle in the Solfèges pour servir à l’étude dans le conservatoire de musique (c.1802), method intended for both singers and instrumentalists.

"In order to nuance the singing phrases, and to give them style and turn, it is essential to clearly mark the strong beats of the bar on which the good notes of a chord always fall."34

The accentuation of strong beats has to do with the notion of aplomb and the purpose of clarity of rhythm and tempo. The importance of this accent depends on the character and tempo of the piece. Berr repeatedly states that it should be clearly pronounced in pieces with a fast tempo and a lively or light character.35 This idea is also found in Henri Brod's Méthode pour le Hautbois (c.1826):

"In lively and light pieces, it is good to slightly stress the beginning of each bar and often even all the strong beats, in order to well determine the rhythm of the music and to make the movement more intelligible to those who listen to it."36

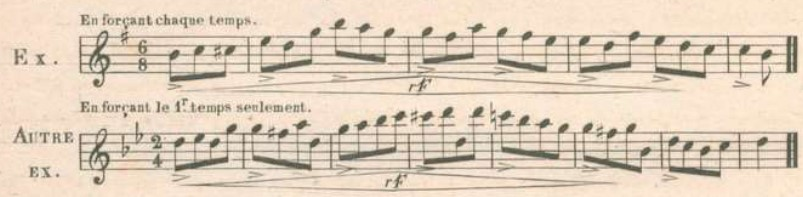

Berr also suggests accentuating the first note of each beat of the bar in a passage work.37

Finally, in pieces with a slow and graceful character, the accentuation of strong beats should be more subtle, the priority being rather to play with an equal and continuous sound.38 39 As can be seen in the example, the articulation is enough.

Syncopated notes

The way of performing syncopated notes is not particularly detailed by the different authors in the first corpus of Conservatory methods. However, some examples suggest that they should be performed with a specific dynamic, in Lefèvre's method for instance.40 He suggests starting these notes stronger before decreasing the sound.

In later writings, the execution of syncopations is often the subject of more detailed explanations and several examples focused on this issue can be found. Frédéric Berr may have been influenced by Dauprat's Méthode de cor-alto et cor-basse (1824). Indeed, we find literally the same explanation in both tutors:

"In all the movements, and whatever the dynamics given to the syncopated note, it must always be attacked with more frankness or energy than the other notes.”41 42

After the attack, the sound should be gradually and continuously decreased.

Performing a rinforzado on the second part of the note is discouraged in the sense that it could sound like two notes when there is only one. The only exception to this rule is when the syncopation is written by slurs between two notes and the rinforzado is indicated on the second note by the composer.43 44

The same general recommendation can be found in Garaudé's method. Nevertheless, he adds a little nuance to this rule, suggesting a difference in execution according to tempo and thus character. A slight inflection is sufficient in a slow movement, whereas in a faster tempo this inflection should be more marked. This is particularly the case for syncopations which are a characteristic element of the piece, for example the Polonaise.45

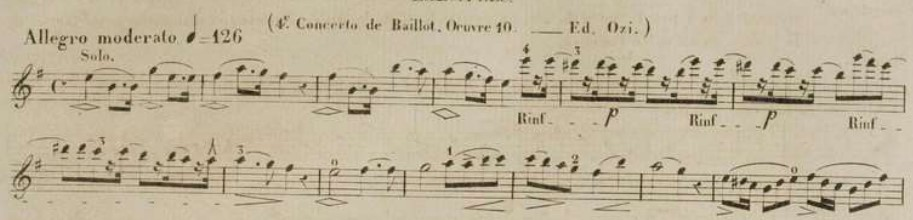

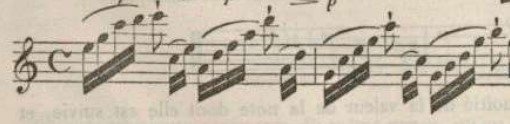

Finally, in L'Art du Violon (1834) Baillot describes three main ways of performing syncopations.46

The first option is to play these notes with a slight crescendo. In this case, the note must be finished without harshness. To this end, Baillot suggests thinking of this way of playing syncopation as a messa di voce, meaning that the end of the note should be very slightly and rapidly diminished after playing a crescendo towards its middle.

Surprisingly, this option is similar to the way of doing things proscribed by Berr and Dauprat, and does not fall within the exception they describe.

The second option is equivalent to the one described by Berr, Dauprat and Garaudé.

The last option is to make the syncopated notes equally and continuously, without dynamics, and to leave the accompaniment to mark the strong beats.

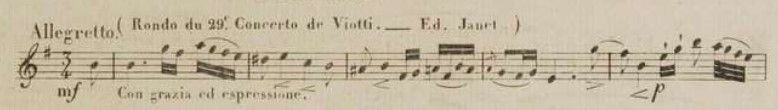

Baillot shows no preference for either one of these three ways of playing syncopated notes. The choice depends on the character of the music and the nature of the accompaniment. Indeed, the author suggests using the first way in a passage where the composer asks to play Con grazia ed expressione, while the second way is suggested in a Scherzo Allegro passage, with a more lively and lighter character. Finally, the third manner may be appropriate if the nature of the accompaniment allows for a clear distinction of strong beats.

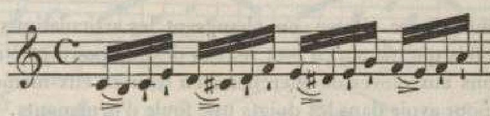

Sons coupés

Berr defines the sons coupés as:

"Notes slurred two by two, and separated from those that follow by a short rest."47

It is the first of these two notes that must be accentuated.

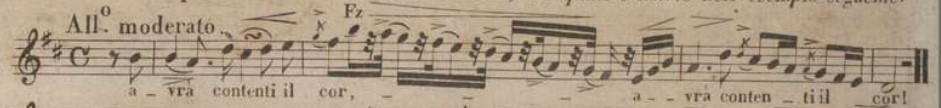

Garaudé identifies the different characters in which sons coupés executed in this way can be found. They are suitable for example for a graceful character. For this one, he refers in particular to certain Cavatines by Rossini. They can also express a painful character and a strong emotion. In this case, the son coupé makes it possible to represent the impossibility for the protagonist to articulate the sounds with equality, and the need to separate them by sighs of pain. He refers to the singer Crescentini who knew how to give a pathetic expression to the sons coupés in Zingarelli's Romeo et giuletta (1796) at the end of the aria Ombra adorata aspetta. This passage is given as an example by Garaudé.48

The Notes jetées have a similar execution to the Sons coupés. They are also notes slurred two by two but the second note is indicated as detached, usually by an elongated dot.49This notation indicates that the second note must be left quickly.

This way of leaving the second note may suggest a use in a lighter and brighter character.

Garaudé's example shows that this way of executing the sons coupés, by stressing the first note, was already used in the 18th century, at least by some Italian singers. This practice is not explained in the first corpus of Conservatory methods and is only detailed in later methods. A few years after Frédéric Berr, Klosé also wrote a part of his clarinet method about sons coupés and notes jetées. He suggests that, in general, all notes slurred two by two, even if they are not followed by a rest, can be considered as sons coupés or notes jetées.50It seems that whatever the notation, the proportion of inflection on the first note and the way of leaving the second will depend on the character of the musical passage.

General dynamics / Specific dynamics

In order to find the right degree to give to these different dynamics, it is also important to consider whether these dynamics do not depend on a more general dynamic. Thus, the degree of strength of a son filé or a phrase filé will not be the same if the general dynamic of the passage is indicated piano as if it is indicated forte. Likewise, an inflection on the strong beat of the bar can be integrated into a crescendo that applies to several bars.

According to Garaudé, the dynamics indicated by the signs f, p, pp are permanent dynamics. In this sense, they are supposed to remain valid until the appearance of another such sign. The signs crescendo and decrescendo are inflections that are called temporary. They do not call into question the validity of the permanent dynamic. They must take on its colour.51The permanent dynamics are more general than the temporary ones, which are therefore specific. We find the same idea in the Méthode of Henri Brod,52 as well as in the writings of Frédéric Berr who explains that:

"The dynamics are also executed in the phrases marked forte, as in those marked piano; in the latter case, the piano must be executed pianissimo, and the forte half-forte."53

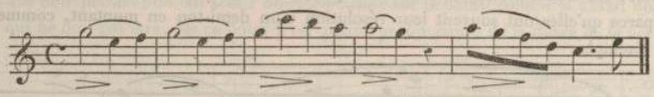

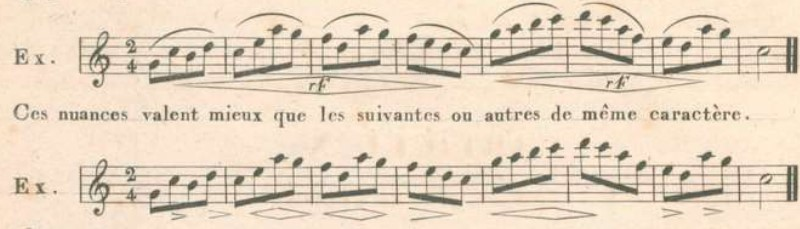

Regarding the inflections mentioned above, crescendo and decrescendo, Berr and Brod both say that it is better to use them broadly and therefore avoid too many small dynamics. 54 55 In the following example, Brod shows two ways of using the dynamics. The first one must be preferred.56

Nevertheless, this does not prevent inflections on the strong beats in the lively movements. Its force has to follow the more general inflection. The general dynamic in this case corresponds to the crescendo and decrescendo over several bars. The emphasis on the strong beat is a specifc dynamic.

Triplets

According to Berr, in order to underline the marked character and the particular rhythm of the triplets, it is necessary to accentuate each strong beat, that is to say the first note of each triplet.57

Leading tones / Accidentals

Like appogiatura, leading tones and accidentals represent a harmonic tension that is resolved on the next note. Therefore, Berr suggests the use of a dynamic on these notes.

Example 10. Berr58

Example 7. Berr59

Example 11. Berr60

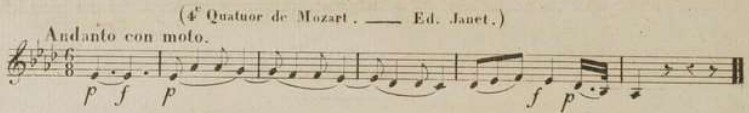

Example 12. Lefèvre61

Example 13. Berr62.

Example 8. Garaudé63

Example 14.Berr64

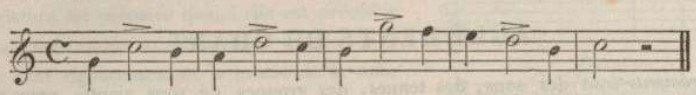

Example 2. Lefèvre65

Example 19. Berr66

Example 18. Garaudé67

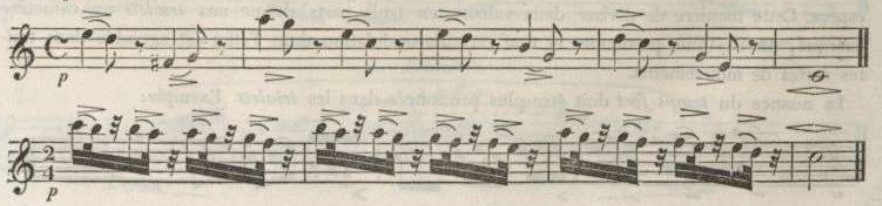

Example 23. Brod68

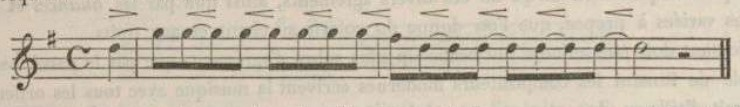

Example 1. Berr69

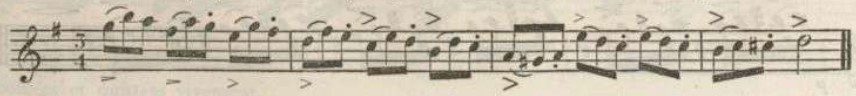

Example 20. Berr70

Example 21. Berr71

Example 3. Baillot72

Example 22. Brod73

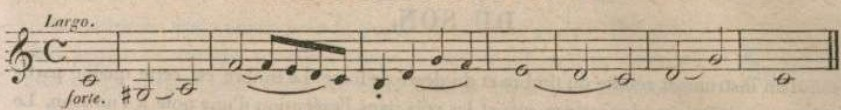

Example 4. Lefèvre74

Example 15. Baillot75

Example 16. Baillot76

Example 5. Garaudé.77

Example 6. Berr.78

Berr. Example 1779

Next: Conclusion

Example 9. Berr80