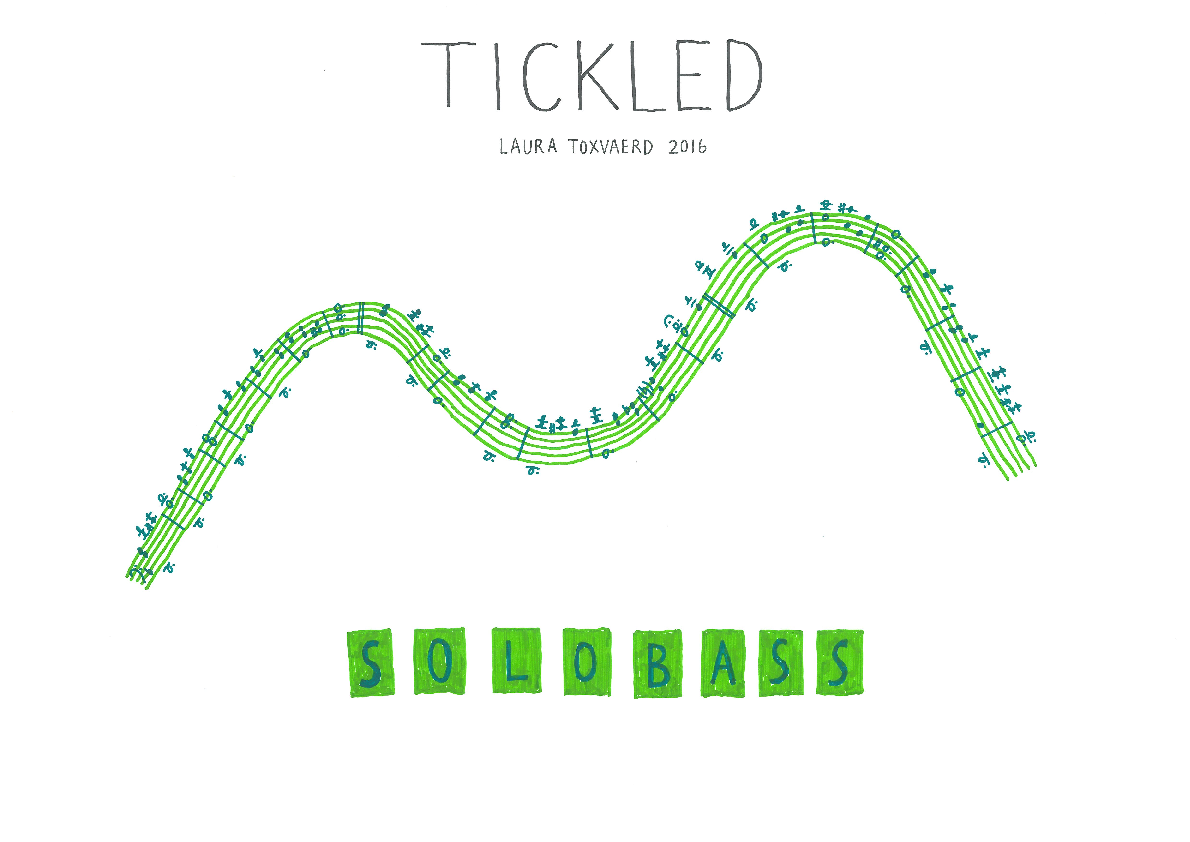

In the final round of working with the compositional process that had led to the creation of the compositions, T and TIC, I chose to alter the tonality and mode of the simple melody in F major, and to voice it, instead, in the relative minor, D minor. The happy and straightforward melody had suddenly become sad and melancholic. What I was thinking was that the new melody bore some kinship to the old one, but that it was now “dressed” very differently. I called the composition TICKLED. I thought that it would be interesting to have the new melody sung by two voices, each with its own line, and bolstered by the additional voice of the double bass at the bottom. So, I notated the three-voiced melody in bass clef, and arranged it so that it could be sung by a female alto and a male tenor. I also added lyrics to the melody and decided that the last part of the composition would be a solo bass improvisation.

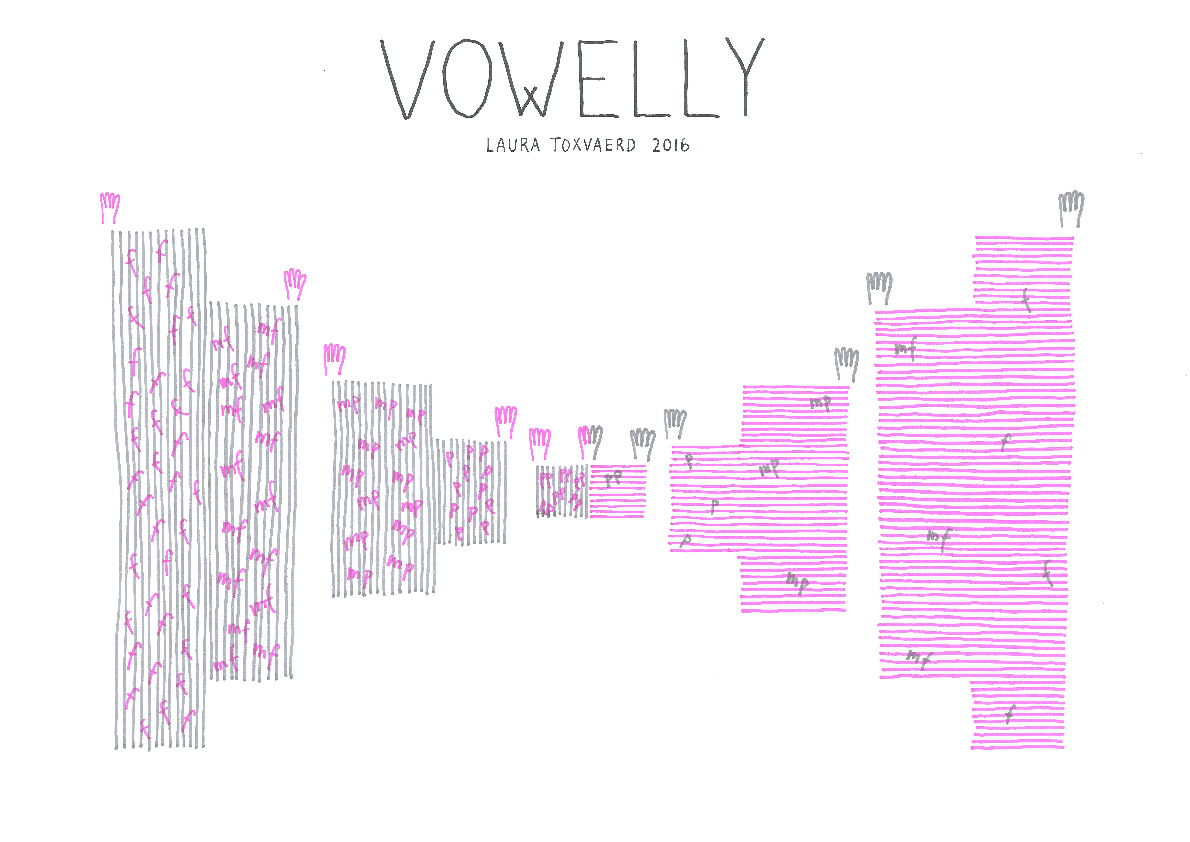

I then moved into the final round of the compositional process that had so far led to the compositions V and VOW. As with V and VOW, I wanted to make the new composition sonically recognizable by means of its dynamic development. But this time around, the changes in volume would transpire in distinctly separated and clear steps. I imagined the volume of the composition to be something akin to walking up and down the stairs.

This would stand in contrast to what was supposed to happen in the compositions V and VOW, where the volume was changed gradually, as if you turned the volume down and then up again with a knob that controls the amplitude.

The beginnings and the endings of the compositions V and VOW, as well as the interruptions of silences in those pieces, were conducted by one of the musicians. In this new composition, which I named VOWELLY, the shifts in volume were also to be conducted by one of the musicians in order to change the dynamics immediately. Because of this, the improvising musicians were going to have to react on even more signals from the conductor than they had to react on in V and VOW. I was fully aware that this was going to pose a challenge for the musicians in relation to co-creating meaningful improvisations in the composition.

Whenever you improvise, you follow a kind of idea that, in the moment, it becomes part of the music as a whole. But when a conducted signal continuously interrupts your improvisation, you are forced to adjust your idea again and again. This constitutes a disturbance of your own way of building musical meaning as an improvising musician. In this composition, I wanted this disturbance to make its impact on the musicians’ improvised co-creation. I was curious to hear how this would affect the music of the composition.

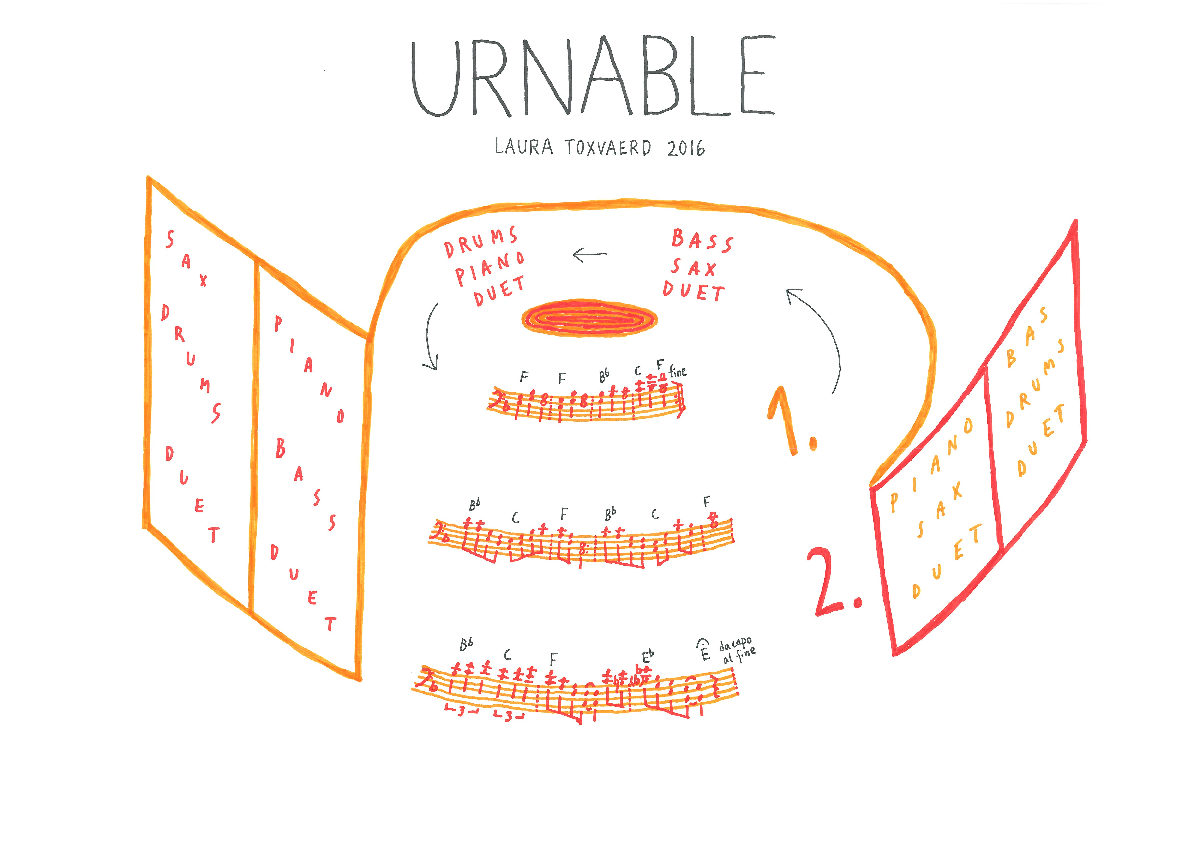

When I returned to the compositional process and re-examined the compositions of U and URN, the first thing that I wanted to do was to alter the melody in some way.

Unlike what I did with the melody of the composition, TIC, which I changed from major to minor, in the composition of TICKLED, I would now move in the opposite direction: the melody in URN was voiced in F minor, while in the graphic score of URNABLE, you’ll find that the melody is set in F major.

I have also replaced the clarinet with a female and a male voice. And I changed the highly personal and non-authorized notation for the clarinet, and notated the new melody in bass clef, while arranging it for the two voices, with added lyrics. I wanted the melody to appear twice in the composition, framed, and also interrupted, by a sequence of different improvised duets.

In elaborating of the design of the graphic score of URNABLE, I made sure that all possible combinations of duets would be presented in the musicians’ co-created and improvised performance of the composition.

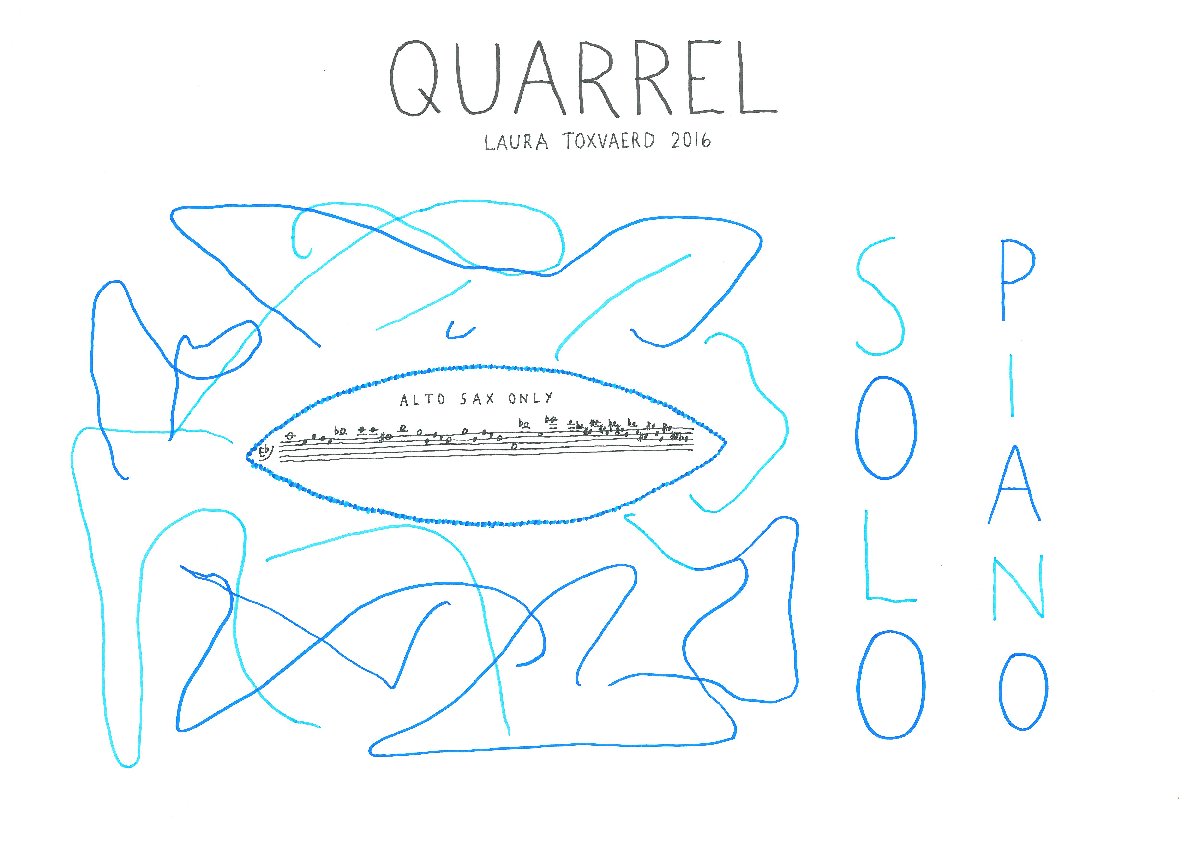

Now it was time for the final round of the compositional process that had resulted thus far in the compositions Q and QUA. I felt an urge to rethink the elements I had originally worked with. I wanted to attain an overall texture improvised by all the musicians.

Their co-creation was not supposed to follow indications of any sort of rhythmic layer. They were merely free to interpret light blue and dark blue soft interweaving lines. This co-created improvised texture was separated from the melodic fragments that the alto saxophone would play every now and then. I scapped the chords that were conjoined with the melodic fragments in order to open up the space around the fragments and encumber them with some modicum of alienation in relation to the surrounding texture.

When the alto saxophone entered with the sketched-out fragments, the other musicians shouldn't be surprised and not change the way they were playing and improvising as an unintended consequence. Therefore they had to remain aware, and had to keep an eye out for this sudden accidental happening. That’s why the alto saxophone melody in the graphic score is written in the shape of an eye. I named the composition QUARREL, and decided that the pianist should improvise, solo, in the last part of the composition.

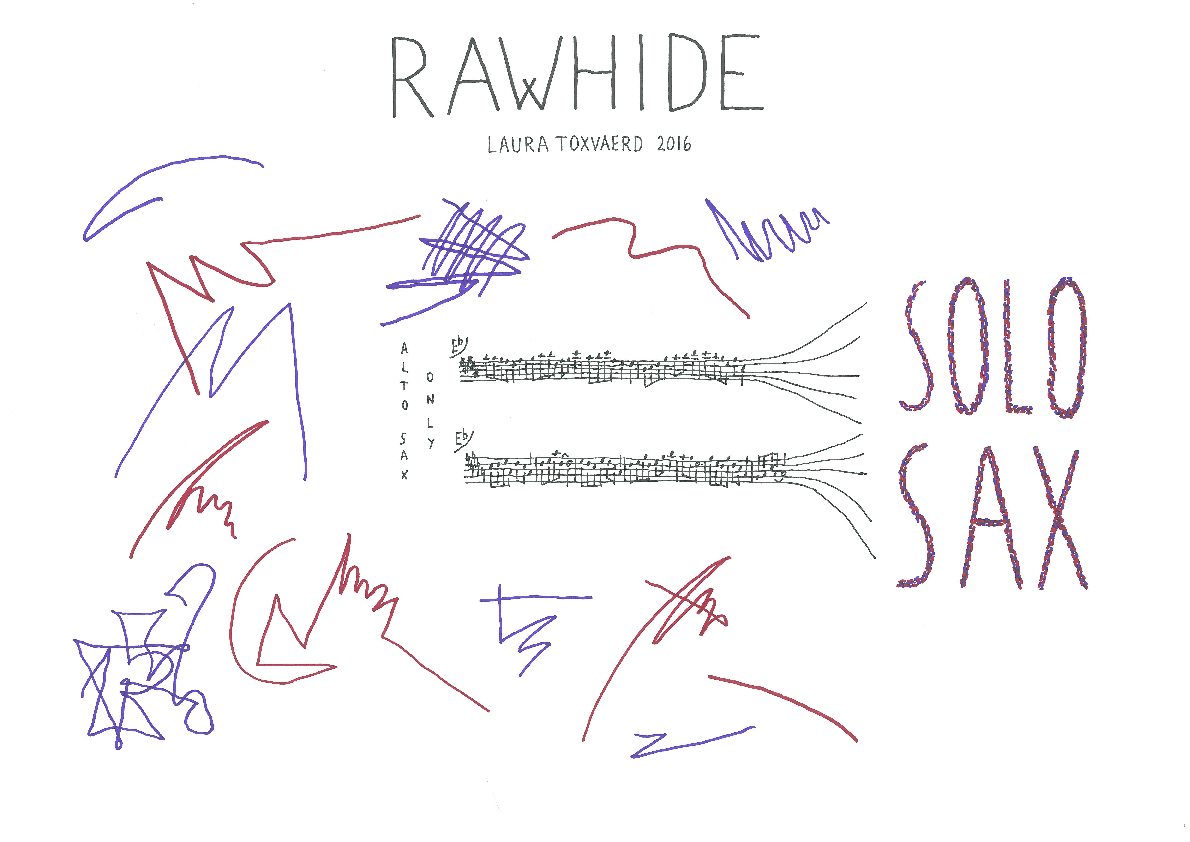

In the compositional process that, up until that point, had resulted in the compositions R and RAW, I had not yet trained my primary focus on the order of the events in the composition.

When I compose, I regard the things that are going to happen in the composition as events that I can arrange in different ways. Accordingly, I wanted to play with the possibility of shifting what was, earlier on, my starting point into a new – and perhaps even more appropriate – position as the final event of the composition.

I decided that the composition should end with the alto saxophone playing a solo improvisation, and I also came up with the idea that the lines of melodic material should function as a jumping-off point for the alto saxophone’s solo. And in this way, I managed to fix the last two events of the composition – namely, the melodic material played, towards the closing of the piece by the saxophone, and then, following this the saxophone’s solo.

Before these two events were to occur, however, I wanted the pianist, the bassist, the drummer and, optionally, the alto saxophonist to establish a co-created collective improvisation.

In the graphic score of RAWHIDE, I designed mostly separated sharp lines in burgundy and purple colors, to be interpreted by the musicians as they play together.

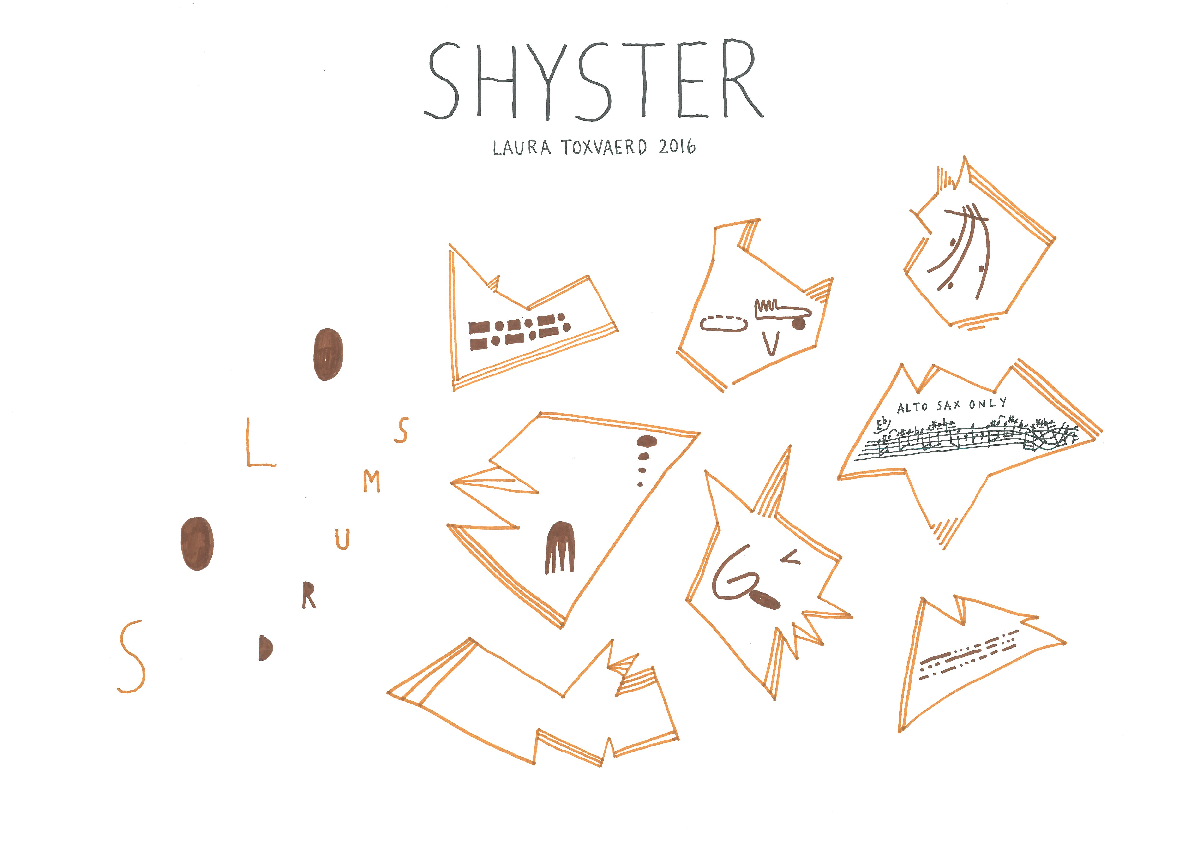

Again it was time for the final round of the compositional process that had brought about the compositions S and SHY. I realised that the most remarkable thing that had happened during this compositional process was that my original idea of a groove had mutated into what I considered “almost groove/nearly time”.

In the graphic score of SHY, I had indicated the now-dissolved connection among the instruments by giving four separate lines of graphic indications to, respectively, bass, drums, alto saxophone and chords (piano). In this new composition, which I called SHYSTER, I wanted to carry the mutation of the groove and the dissolving of the connections one step further toward a more complete atomization. Taking the compositional consequence of such an atomization necessitated isolating the different events that the improvising musicians were co-creating.

I underscored this in the graphic score of SHYSTER by designing sharply and obliquely inclined (leaning) light brown shapes that circumscribed possible and optional dark brown events going on, which were illustrated inside of these modified parallelograms. What I thereby indicated was to be no coordination, rhythmically – instead, the rhythmic aspects should enter into the music in an unplanned and unforeseen manner. Additionally, I decided that an improvised drum solo would be played at the opening of the composition.

Excerpts from my concert with Carsten Dahl, Raymond Strid & Jonas Westergaard in Jazzhouse Cph (YouTube video) LINK