Acting background

When I am analyzing a script, I get to look for what will justify my character’s actions in a way that is logical for me. When working on portraying the people I create, I get to experience so many different characters. In creating backstories and understandings for such a great variety of personalities, I have even found myself bringing these analyses into my personal life. This work of trying to understand everyone’s actions and creating backstories for people fed further into my curiosities and search for why people chose to do what they do. What sparks their behavior? I constantly ask myself why people act a certain way and say certain things. What do they want to achieve with the way they are acting? And why now? Is there a way for me to understand their logic? And is there logic behind it at all? The tools I use to analyze a text are based on what I learned during my Bachelor of Fine Arts studies at Long Island University as a part of the toolbox of acting techniques I started developing there. The technique that I use the most from this toolbox is based on the teachings of Konstantin Stanislavsky, which he wrote about in his book “An Actor Prepares” (1936).

Konstantin Stanislavsky was a Russian actor and director who is considered the father of psychological theatre. He created a system for actor training and rehearsal techniques at the beginning of the 1900s. He used the strides made in psychology and brought those into the theatre and the way he worked with creating the characters in a play (BBC, n.d.). He started analyzing plays and worked with the “art of experiencing” rather than “the art of representing” (Curpan, 2021; Stanislavsky, 1936). In the world of film, where we get transported into the story and can see the actor’s tiniest movements, the “art of experiencing” has become more central than ever. I use this technique when writing and directing as well because it allows me to gain a better understanding of the world of the story, as well as the characters living in it. Here is a summary of how I work with Stanislavsky’s technique as an actor:

Given circumstances

The first step when working with Stanislavsky, after reading the whole script of course, would be to create a document called “given circumstance”, which is a part of the script analysis. This document allows me to freely create my character based on the information given about her in the script. This is something I do as a director as well, but for all the characters in the project, to gain an understanding of their personalities, inform the direction and make it consistent. The document I create as a director is only for me, and as a director I ask the actors create their own documents, which they will fuel with their own interpretation of the character that is based on their world view. In working this way, the director allows the actor to build a character that is true to themselves and make the character achievable because it is true to their understanding of the world.

So, what does this document include?

First, I go through the whole script and write down the following:

1. What does the playwright say about the character (character descriptions)?

2. What does the character say about themselves (dialogue)?

3. What does other characters say about the character and how much of that is truth (dialogue)?

Through these three questions I find the answer to all that the play dictates the character to be. Other than this information I have the freedom to make up anything you want about the character.

The main questions to answer in the given circumstances are:

1. Who am I?

2. Where am I (in each scene)?

3. Where am I coming from?

a. Distant past

b. Near past (for each scene)

4. Where am I going (in each scene)?

5. What is my relationship?

a. With the people in the scene

b. With the people mentioned in the scene

c. With important objects in the scene

Notice that the questions are written in the first person. This is so that the actor will take on the character when answering these questions and be allowed to take on their experiences, and even add their own experiences to fuel the character further.

Who am I?

This question is about the characters personality. Am I religious, what is my political stance, how do I see myself? It’s a short biography, an introduction into the life of the character. I often use this as a springboard to get to know the character more and write freely, exploring her within the frames given by the playwright.

Where am I?

Here the focus is on the time and the space. What country am I in, city, area, etc.? What time of day it? And what time of year? Is it dark outside? Is it hot? Have I been here before? How many times? What is my relationship to this space? And what do I see around me? Is there I big clock on the wall reminding me of how late I am? Or maybe comforting music that makes me want to lay down? Some of these questions might be answered by the author, but others might have to be imagined. For this question it would be a good idea for the actors and the director to be on the same page. Especially when it comes to temperature and time of day, which might have a big impact on the other actors’ interpretation of certain situations, like the opening of the window.

Where am I coming from?

This question is divided into two parts: Distant past and near past. Distant past can start in early childhood if that is needed, talking about how the family moved to a different city or whether I was adopted etc. This is to fuel the backstory and biography further, to bring up memories that could influence the way something is perceived. Near past applies to where I came from right before I entered the scene. Did something happen that influenced how I am entering? Perhaps I was being chased and managed to escape, or I came in from a snowstorm? The choices are endless but should be linked to the story and the intensions of the playwright. These choices will then also fuel how I enter the scene, therefore it’s good to make some unexpected choices that will add to or change the perception of the scene. These choices are great to play around with during the rehearsals.

Where am I going?

It is possible to add a distant future for this question as well, which will have to do with the character’s goals and objectives, something I will discuss later in this text. The main part to answer with this question is where I am going after this scene ends, physically as I am leaving the stage. Maybe I have somewhere I have to be and therefore need to rush out, or I am going to the dentist and therefore trying to stall as long as possible and be late for the appointment. Visualizing where I have come from and where I am going, especially if where I am going is a known space to me, will hopefully help adding to the “art of experiencing” as I will allow myself to really be there in my own mind.

What is my relationship?

This question is especially fueled by what is written by the playwright. I pick up clues on how the character talks to and about the other characters present. Also, I use the “Who am I” and “Where have I come from” to help interpret how the character would feel about the other characters that are interacted with or that are being discussed. This part of the given circumstances demands good knowledge in understanding human behavior. Dissecting the text might be necessary to understand how the character really feels about the people around them. It is also important to take into consideration that the characters might be lying in the dialogue, like we also do in real life.

Under relationship it is essential also to explore any significant object in the scene. If it is an auction where the character’s favorite jewelry is being sold, adding a backstory to the connection between the character and the jewelry might help when working on “experiencing” the difficulty of giving the object up. Here, I sometimes work on imagining an object that I was connected to in my childhood and applying that to the new object, to give it meaning to myself as well as the character.

Scoring

The second part of the script analysis is to go through each scene and find out what the character wants, both overall in the script, in each scene and for each beat, which I will explain further. Through this process I use what I have learned about the character through the given circumstances to fuel the needs and desires of the character in the different sections of the script. As a director I would do this for every character as well, keeping in mind that the beat changes might be a little different for each character. Here it is good to keep in mind that the “juicer” the choice, the more I have to play with, so I tend to be bold to make the scenes even more interesting. The scoring is a living document that is going to change a lot during rehearsals, I always write these with a pencil to be able to change them around a lot.

Objectives

An objective is the character’s goal, the wants or needs at a certain time. The first objective I make is called the super objective. This is the character’s overarching objective through the whole script that may or may not be fulfilled in the end. For example, in Batman, his super objective can be to catch the bad guys. Sounds simple enough. But in creating a super objective, I need to make sure that my scenic objectives, the objective for each scene, mainly are created to support my main super objective.

The structure of an objective can vary a little, but I like to use it as a sort of a mantra for the character. I mainly structure the objective like this: I need ___ in order to ___. So, in the case of Batman I would for example write: “I need to catch the bad guys in order to avenge the death of my parents”. Here I have a lot of “juice” by bringing in the personal tragedy, and it gives me plenty to take from when creating scenic objectives.

The scenic objective is closely connected to the scene and what is happening, therefore it is often a little more specific, but I am still creating it with the same formula: I need ___ in order to ___. And lastly, there are the beat objectives or immediate objectives, which are even more specific, and that also allows me to play around with different tactics to get the other person in the scene to help me get what I want from them. I will get more into tactics later.

Beats

When going through the scenes of my character I divide the scenes into beats, where each beat has a new objective. The clearest way of finding the beat change is to look for where a discovery was made by the character, alternatively, where the scene changes focus. A beat change can therefore be defined as a change in action or intention. This can for example be when a new character enters, or when some new information is being revealed, or a change of topic. It can also be a change in tactic, when this is clear in the text, but this I will also get back to later. Here is an example of a beat change from the Godfather:

Here it is a clear change of topic, which also is a tactic change by Don Corleone. It changes the flow of the conversation and at the same time what the characters want from the other in that moment. Finding the beat changes is something that should come naturally, and the more you look for them, the easier they get to spot.

Actions

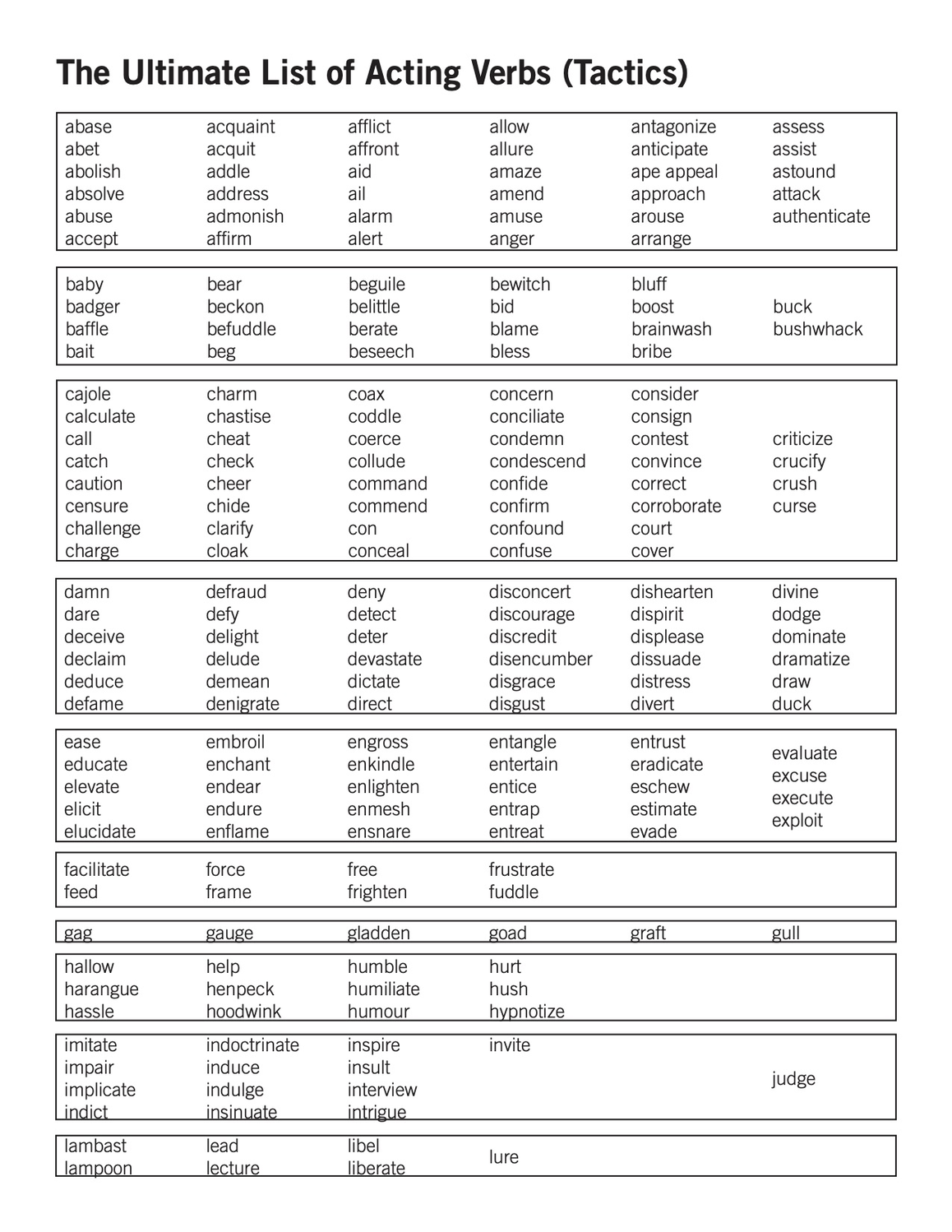

After having gone through the scene finding a scenic objective and an objective for every beat it is time to look at every line of dialogue. How do I want the line to hit the other person that I am talking to? Here we have a list of acting verbs, that are active verbs describing how we want the action to land on the other person. This list can be viewed as tactics on how to get what you want from the other person in the scene. There are many ways of saying a line, by using this method I connect the delivery of the line to the objective, thereby using the objective to fuel your acting in trying to persuade the other character to give me what I want. The actions are something I tend to play around with a lot in rehearsals, trying out different actions and seeing how that affects the other actor in the scene. I go for the juicier choices here as well. In working this way, I may find new ways of performing the script and experience new meanings in the text, which is a fun experience and makes the performance more unique.

Delivering the line with the right action is something that at times might be difficult, especially in finding the nuances. I sometimes will use my body to manifest the action there while saying the line, in order for the line to get the right intension. For example, the action “to pull”, I will pretend to have a rope between my hands that is connected to the person I am talking to and pull this towards me while saying the line.

Obstacles

The fourth section to add when scoring a script is the obstacles the character is facing in the scene. This can for example be that there is a baby sleeping in the next room, so I don’t want to wake it up, or it can be more connected to the person I am talking to, like that I need to be polite even if they are being difficult. The obstacles are important to note down for every beat because they will influence how to act the scene. It is, of course, allowed to go against the obstacles, but in doing so, the consequences need to be added to the story. This means that for example if the character yells, the baby might wake up, which means there needs to be made a choice on how to handle that situation. Does the character leave the stage to calm the baby down, or maybe yell for someone to take care of the baby, or even just let the baby cry until it falls back asleep? Playing with and against the obstacles makes the scene more dynamic to watch, and also raises the stakes put on the actor, which allows for a more complex character that the audience will believe in.

Conclusion

This was a brief overview of how I work with the Stanislavsky technique. Using this method before going into rehearsals as a tool to get further into the understanding of the script and the character, makes the rehearsal process more efficient for me. It allows me to get straight to work with deeper and more personal understanding of the character and their actions, as well as giving me an efficient list of things to test out during the rehearsal process. It also allows me to test out more tactics and see how they land on the other characters in the scene. Going for the unexpected approach to a text might help make it more impactful, in that it throws the audience off guard and can lift the script to a new level.

INT DAY: DON'S OFFICE (SUMMER 1945) DON CORLEONE ACT LIKE A MAN! By Christ in Heaven, is it possible you turned out no better than a Hollywood finocchio. Both HAGEN and JOHNNY cannot refrain from laughing. The DON smiles. SONNY enters as noiselessly as possible, still adjusting his clothes. DON CORLEONE All right, Hollywood...Now tell me about this Hollywood Pezzonovanta who won't let you work. JOHNNY He owns the studio. Just a month ago he bought the movie rights to this book, a best seller. And the main character is a guy just like me. I wouldn't even have to act, just be myself. The DON is silent, stern. DON CORLEONE You take care of your family? JOHNNY Sure. He glances at SONNY, who makes himself as inconspicuous as he can.