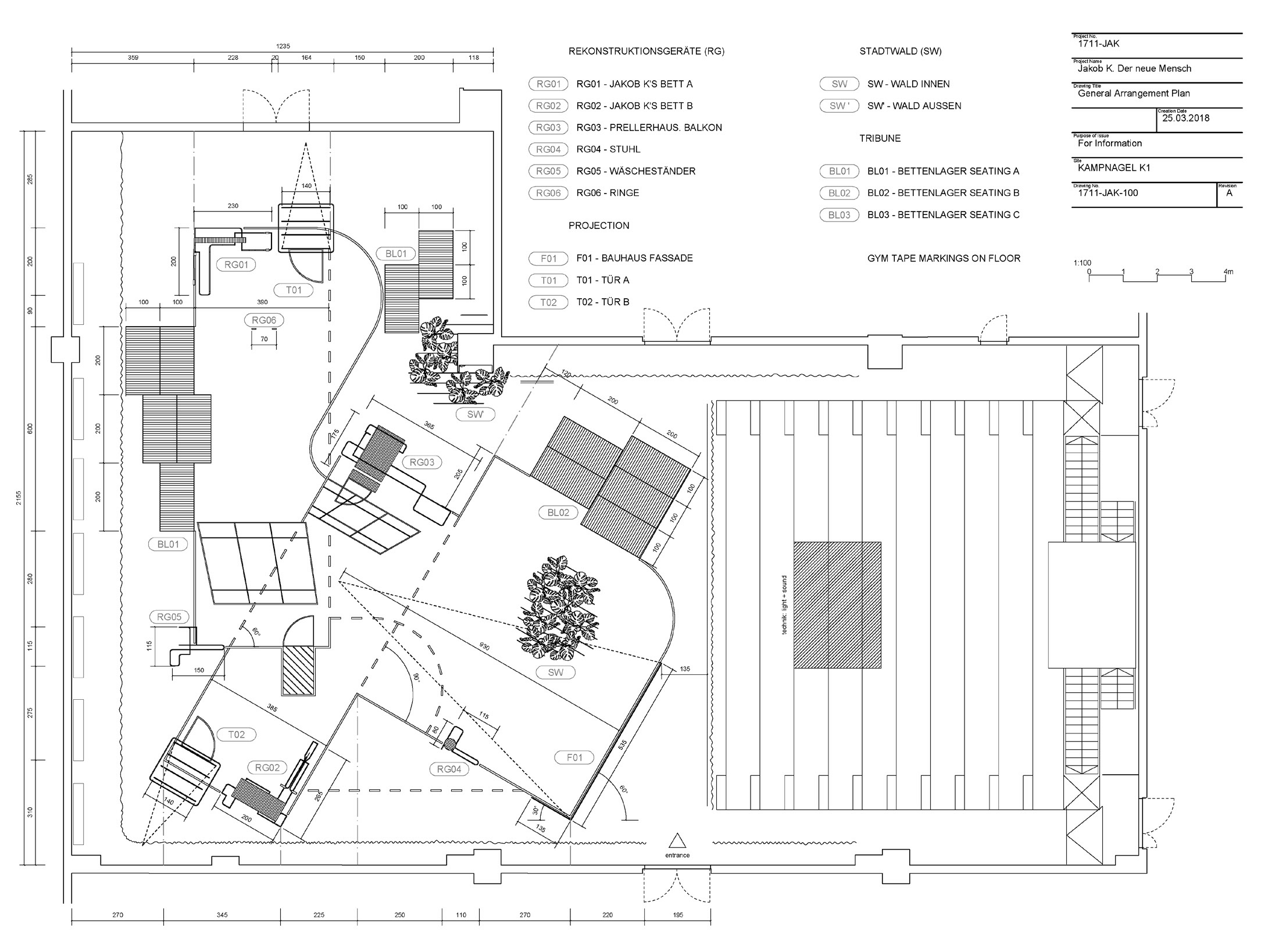

Once constructed, the masks are then, like the RGs, disobediently activated by the performers, often subverting the designers’ intentions. When drawing and building RG02, for example, we had imagined the seesaw exercise mask to be operated by a performer sitting on the bed, who would impress the mask upon the face of a performer kneeling opposite. This perhaps all-too simplistic and hierarchical relationship (operator-stamp-stamped, subject-tool-object) was however readily inverted during the rehearsal process: the mask was instead operated as the lever to control the opposing exerciser. Identity is work.

However, concluding the description of these masks, some self-critical reflection seems appropriate. How are our masks different from Schlemmer’s own costumes, sculptures and reliefs, in which he subjects the human figure to various geometric grids, cutting it into component parts to highlight the kinship between machine logic and fractured body? How are they different from the aforementioned cubist fragmentation of L’Arlessiene, which Giedion had hailed as a visual touchstone of modernist architecture?

On the one hand, their aim is certainly different: if Schlemmer’s sculpture – similar to his masks that were used as a means of deindividuating the performer – intends to depict an abstract and idealised Man (‘Mensch’ [see Schlemmer 1969]), and if L’Arlessiene grapples with one subject’s totality by depicting it from varying angles, our masks are more generative, using a combinatorial logic to generate, rather than depict, a novel identity. At the same time, the means to achieve such an aim, the aesthetic and techniques employed, are less novel – perhaps to the point that its language of fragmentation is indeed so known, so engrained in the visual literacy and habituation of a postmodern audience, that the masks’ fragmented identities are unable to unsettle this audience, instead comforting it by serving its expectation pattern.1 Are the masks hence unable to, like the RGs, develop their own open-endedness and associative tentacles, inviting the audience to actively project their own associations, thereby continuing the process of inventing novel identities? In all their efforts to proclaim fragmentation, are these masks merely representing the emergence of novel identities rather than actually instigating the performance of these other identities?2

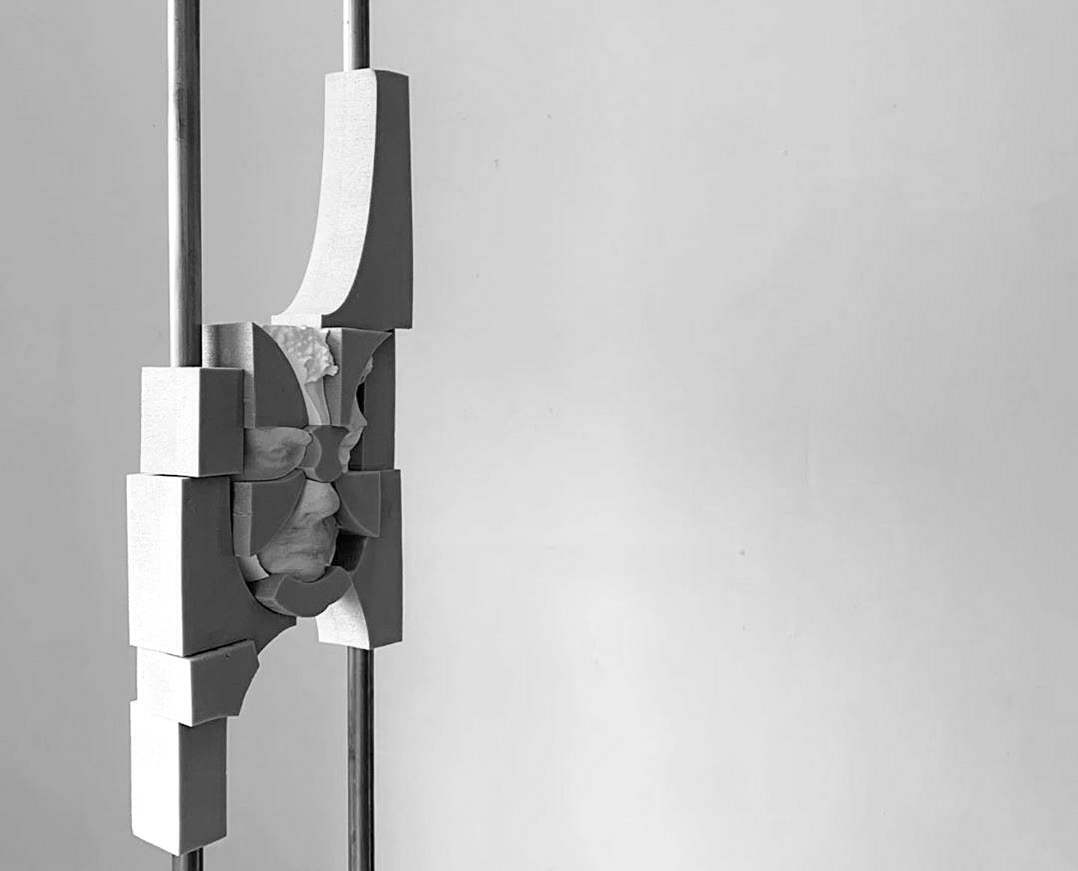

The opposite end of this instrument is covered by a cast silicon handle. As part of the open-ended exercise practice instigated by the training instruments, the handle invites other participants to rotate the Lidar tube’s viewing direction. Elsewhere too, masks can be actuated: one totem-like mask slides up and down the vertical tubes of RG02. Another one is connected through a seesaw mechanism to the movements of an exerciser sitting opposite, on the bed of the same instrument, lifting and lowering the mask by operating a set of handlebars with silicon grips.

The meaning of these masks is consciously left ambiguous – the audience’s likely assumption that they are effigies of Klenke is neither confirmed nor denied. Since of course there is no ‘original’ Klenke, the masks cannot be ‘images of’ but only movements towards, or through, his identity – they reveal the act of reconstruction rather than its object.

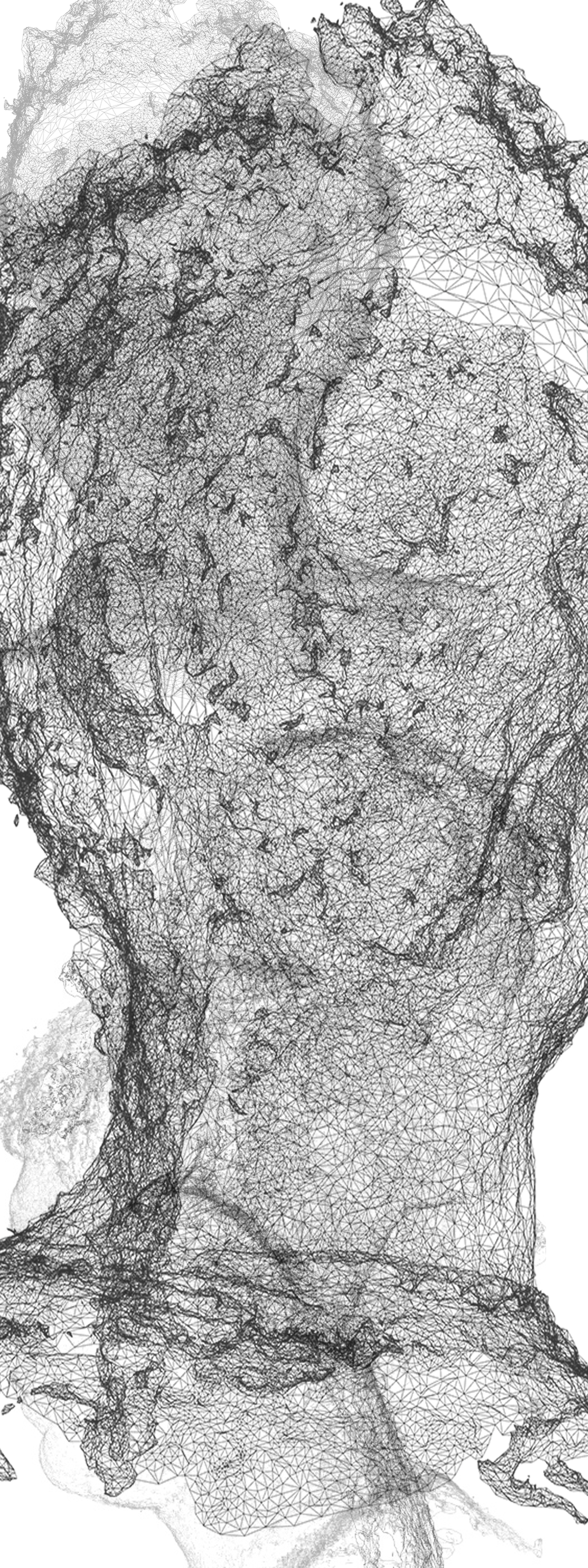

The masks are produced using known techniques of facial reconstruction. As input values, the three performers are 3D-scanned and reconstructed using photogrammetry. The scanned heads are aligned using both eyes and the centre of the chin as calibration points. Then, features like eyes, mouth, nose, chin, and cheeks are separated, using a face-mapping grid. These features can now be interchanged and reassembled: performer A’s mouth and left eye can be combined with performer B’s nose, performer C’s right eye, and so on. The mask’s identity is constructed in a combinatorial procedure akin to the reconstruction of criminal faces on the basis of witness accounts using forensic facial compositing techniques like IdentiKit.

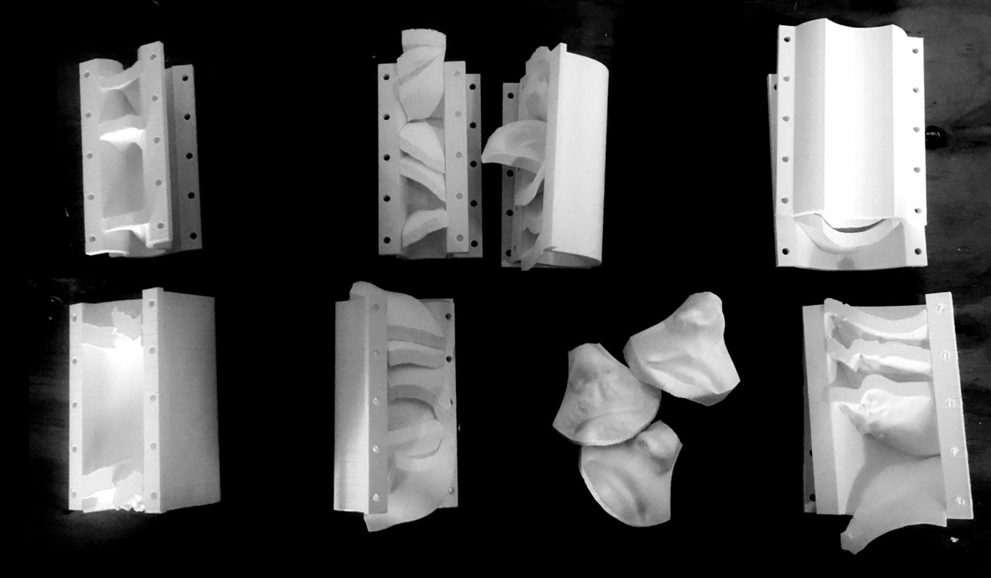

Unlike IdentiKit, however, the masks are composited not from two-dimensional photographs or drawings but from three-dimensional components, which are materialised as silicon casts. The separated features are 3D-printed and are inserted into a two-component mould formed as the extrusion of the drawn face map, capping this tubular mould at both ends. This fabrication process generates a set of peculiar rules. As each feature is only 3D-printed once, it is impossible for the negative feature at the back of this extruded identity tube to be the same as the positive feature at its front. Each of these extrusional identities is hence necessarily one mediating between different input identities – a thick transformative in-between:

- If it is worn by the performer whose negative feature it bears at the back, it will display another’s positive feature at the front (e.g., A-AB).

- If, vice versa, it displays the wearer’s positive feature at the front, it becomes a way of physically measuring the difference between one’s own feature and that of a digitised other, using the cast negative feature at the back as a gauge (e.g., A-BA).

- If neither positive or negative feature match one’s own (as is the case for a third performer, us, or the audience), the cast functions to measure difference and to transform at the same time (e.g. X-BC).

In the next step, the masks are composited by combining the cast silicone components with the original 3D-printed moulds (note that these, as opposed to the silicone components, have identical negative and positive features and hence replicate input and output identity, e.g., AA) with neutral foam blanks, cut from the same foam as is used for the audience seats and the RGs’ beds. A fractured mix of materials and features, neither male nor female, results.

The masks misuse the IdentiKit as a set of rules with a generative capacity. As was the case for the RGs – which subverted the logic of fitness instruments as a disciplinary apparatus aimed at moulding an idealised, normalised, and productive body and replaced it with an indeterminate fitness practice that eludes purpose and measurability – a disciplinary technique is misused as a creative mechanism, an affordance. If the IdentiKit reconstructs a person’s facial features – assuming a pre-existing identity, which is ‘simply there’ and waiting to be discovered – our disobedient IdentiCuts misuse the rules of facial compositing to split the very notion of identity. The face-mapping grid is used first as a diffractive filter that splits the performers ‘input’ identities and then allows us to construct rather than reconstruct identities, performing them materially and combinatorially.