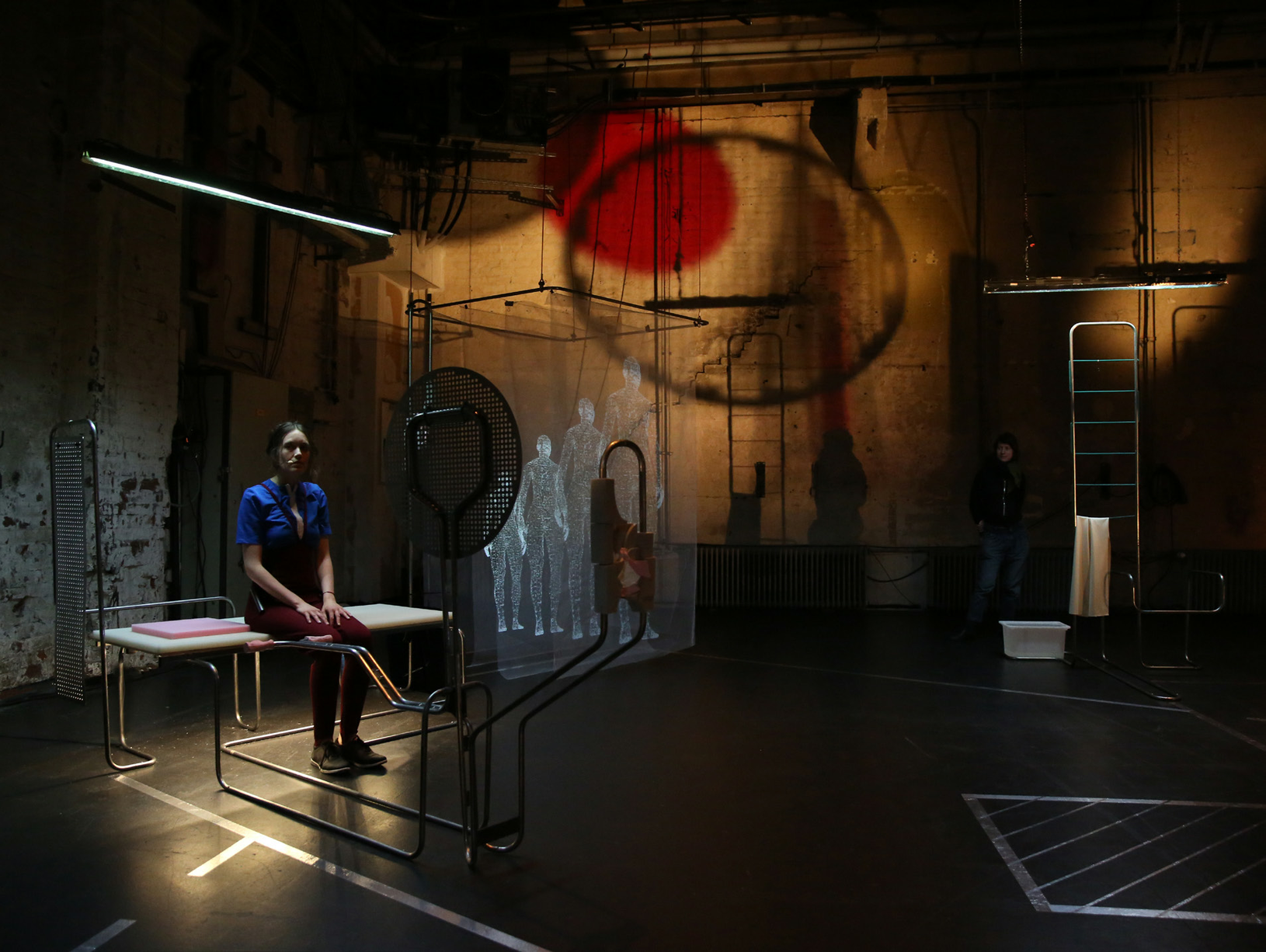

The body has dissolved into a technological assemblage and then it returns as a combinatorial ghost: on the ‘doors’ next to RG01 and RG02 (the suspended layerings of scrim screens), digital avatars are projected as animated wireframe figures. The animations are based on a catalogue of movements from Klenke’s practice, which have been physically enacted (movement per movement, limb per limb) by the performers, filmed and then digitally rigged. In a next step, these individual components are overlaid and recombined algorithmically.3 Projected on stage, this generates a nearly endless virtual repertoire of reconfigured movements. These androgynous digital ghosts, made up of the crossed doppelgängers of the performers’ movements, are life-sized and interact with these performers during the rehearsal and throughout the evening performance, expanding their range of possible movements. Perhaps, these many-armed others are the contemporary equivalent of Schlemmer’s technological others – only that the movement constraints of the machine have been replaced by the ephemeral seductions of the algorithm.

Returning to our fitness instruments and re-evaluating them in the light of this shift from discipline to control, they seem to belong to the logic of the former: the enclosing apparatus of disciplinary power and the prescriptive motions of the factory machinery already alluded to by Schlemmer. Its contemporary successor in a regime of control follows a more dissolved logic: the ubiquitous tracking of performance data operates untethered by physical location or apparatus. If the New Man was collectively moulded, the Quantified Self is shaped by the modulations of our very desires. Contemporary subjectivation is a moving target that constantly and imperceivably shifts according to the obscure rules and demands of the market.

This is not to suggest that techniques of modulation replace technologies of moulding: fitness instruments are unprecedentedly popular and buildings are still enclosed by walls. Rather it implies that another, more sophisticated layer is added to the workings of power. So while it is valid (and indeed necessary) to develop strategies to subvert the workings of disciplinary apparatuses (as we have done with our indeterminate training instruments), it is equally important to – through unpacking the workings of modulation (whether through digital platforms, new extractivist algorithms or artificial intelligences) – simultaneously invent ways of appropriating modulation as a creative and subversive method: ‘There is no need to fear or hope’, Deleuze states when discussing control, ‘but only to look for new weapons’ (1992: 4).

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to express his profound gratitude to Dr. Moritz Frischkorn, whose contribution to this exposition has been invaluable. Jakob K. Der Neue Mensch was a performance and research project by performance-makers Heike Bröckerhoff, Moritz Frischkorn, and Jonas Woltemate, and architectural researchers and designers Mara Kanthak and Thomas Pearce. Other collaborators were Livia Piazza (dramaturgy, artistic assistance), Sergio Pessanha (light design), Gloria Brillowska (costume), Christine Grosche (press, production), and Oscar Maguire and Thomas Parker (research assistants). It was funded by the Hamburg Arts Council, Architektursommer Hamburg, Kampnagel Hamburg, and the Bartlett Architectural Research Fund (UCL).

Conclusion

Because Jakob Klenke never existed, he will continue to be brought into existence. Jakob K. is a practice of ongoing co-invention and co-enactment, an open assemblage that continues to be shaped by its many authors. Still, it is possible to draw some conclusions from the topics explored throughout this exposition.

To reconstruct is to invent. Jakob K. is based on an understanding of reconstruction as an inventive act. By inventing a minor character, a forgotten artist, who – apparently – never made it into history, it points to artistic figures in the margins, to secondary characters and extras, who have never made it to the centre stage. Thinking of Klenke as a methodological tool for the production of alternative historiography implies two central artistic arguments: firstly, history is an ongoing invention, one that is continually being rewritten based on contemporary necessities, positions, and perspectives. Therefore, secondly, there is no necessity attached to historic reality. While, in so far as it has passed, the past may seem factual, one may always ask: but could it not have been different? And, if we remembered past periods differently, what would the effects of such alternative historiography be for our present?

To reconfigure the past is to reconfigure the self. This stirring up of historical narratives and historiographical practices is linked closely to the challenging of entrained subjectivities. To train is to repeat, just like to re-enact is to repeat: training has a historiographical quality, an inscribing of history and bodies through repetition. Yet like the past, which was never ‘present’ and hence cannot be re-enacted or repeated, the subject is no longer simply there, but rather needs to be performed and constantly reinvented. The splitting, reconfiguring, and ongoing reinvention of the historical figure of Klenke, the untraining of his historical body is, as our open-ended training apparatuses have shown, an invitation to simultaneously split, reconfigure, and continuingly reinvent the contemporary training body.

To create is to co-author with human and technological others. The fact that ‘Jakob K.’ is a transdisciplinary project, collectively authored by performance-makers and architects alike, highlights that historical invention is both a social practice and a collective act of creation. More than that, the methods we use within the production of Jakob Klenke’s oeuvre – which range from research of historical fitness manuals to 3D printing and modelling – point to the fact that historical invention is never a human affair only, but is grounded in and entangled with technological procedures and material conditions.

To misuse technologies is to reinvent them as new weapons. The various practices and components of Jakob K. discussed in this exposition’s sections operate through a variety of resolutions and techniques, but follow a common strategy: they take prescriptive mechanisms (of discipline and later of control), logics of representation, and techniques of reconstruction, misuse them in disobedient ways, and reinvent them as creative affordances and ‘new weapons’ that can challenge dominant techniques of power.

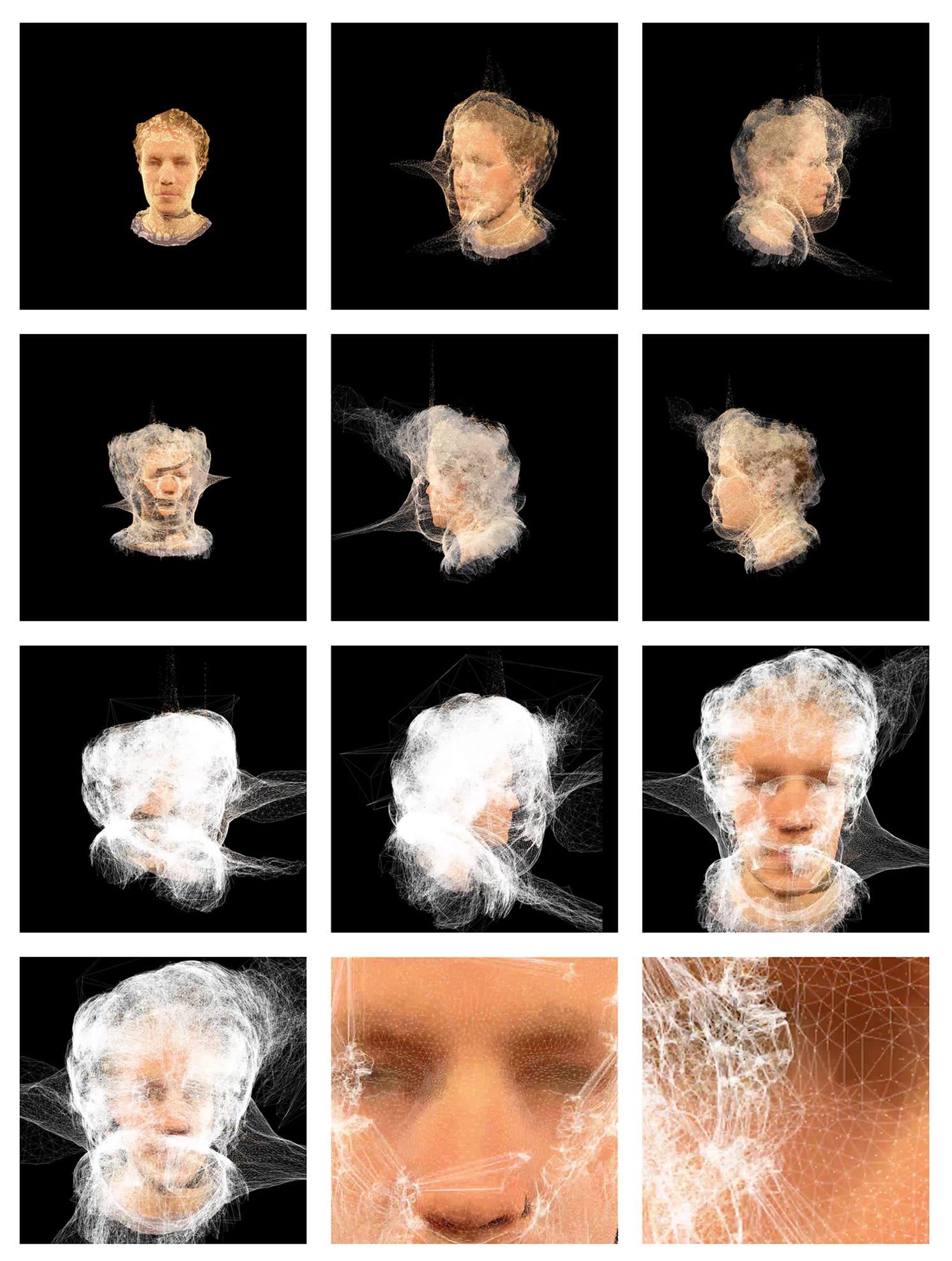

After a couple of initial minutes of roaming and taking in the stage, one notices that the giant mutating head on the screen is doing more than just interpolating between identities. It is starting to pulsate subtly. Its vertices are rhythmically expanding and contracting in sync with the diction of a voice gently addressing the audience. The voice (turn up your volume if you cannot hear it) speaks:

We are not alone. We are surrounded by specks of dust, microparticles of scents, pollen, humidity, little insects. We are surrounded by life. Our bodies are heavy and calm, their weight presses down into the ground.1

It seems like we are being taken through a guided meditation. Yet though this meditation adopts the tone and structure of meditations available on popular apps, it subverts its content, as the suggested visualisations start being contaminated by technical descriptions:

Incessantly, electric impulses travel from our body to our brain. The brain glows, it is cool and heavy. It glitters and weaves threads of light. Threads that grow out of our cortex, through the skull. Through tiny holes in our scalp, they mushroom out and into the air.

The head’s pulsations in the meantime have grown in size and frequency, its white mesh structure becomes more distinct as it grows and shrinks. The crossed identities of the head mutate into ‘glittering and weaving threads of light’: the head is not just a likeness (of Klenke, of the performers), it has also become ‘thread-like’, ‘text-like’.2 Until finally, the expanding mesh spills over the edges of the projection screen:

The threads of light grow further, they . . . envelop plants and other bodies. We start to feel the heartbeat of our neighbours, the electricity running through their muscles, the flow of their thoughts. We feel electrons running through cables, data flowing through fibre optic networks, the subtle vibrations of faraway server farms. A pulsating machine. Total empathy.