2.b) Integration of Ornamentation

Bacilly comprised in the third section of his 1668 treatise a long list that included long and short syllables, and that was also his initial reason for writing this treatise.

At my first intent was to only to shed some light concerning proper pronunciation, and on the length of French words which commonly occur in vocal music, meaning to point out the errors of the former, and to establish some strict rules for the latter…1

What was unique about Bacilly’s description was that he related syllable length to vocal ornaments. As Ranum states, French words are emphasized not by increase in volume, but by the length of the word.2 Therefore, it makes sense that ornaments should be added to the words that are emphasized by the length of the syllable, thus adding force to a word that deserves attention. Bacilly’s lengthy list of long syllables was important to singers, because it was important to identify which syllables were long, so that singers knew where to add ornaments. 3

Bacilly asserted that long syllables must always be given some sort of ornaments, like ports de voix, long tremblements, accents, divisions, and plaintes, while short syllables should only be ornamented with trills and appoggiaturas when there were demands of symmetry or where the clarity of the declamation so dictates.” There were also semi-long syllables, which were not so long but were long enough to be distinguished from the naturally short syllables, where only ornaments like small tremblements, ports de voix, mordents or “repetitions of the throat” could be added.

As Ranum stated in her book The Harmonic Orator (2000), the lengthening of a word is often facilitated by the presence of a final voiced consonant, including /n/, /m/, /r/, and /l/, within that, syllables ending in /r/ and /l/ are only semi-long.

Below is a summary of the method Bacilly suggested for recognition of long monosyllables:

1. All monosyllables which have an s are long.

2. All monosyllables which contain an n after a vowel are always long, provided that the n is followed by another consonant.

3. Monosyllables which contain an r or an l with another consonant, have a sort of privilege of over monosyllables which are naturally short in that the singer can give them some indication of length. (semi-long)

4. The diphthong au is long in the extreme sense.

5. All monosyllables which are on the rhyme or the caesura of a verse or which immediately precede question marks, exclamation points, or other such punctuation marks or which pause because of the meaning of the text or because of the natural pause of the poetry, can be long no matter how short they may be naturally. 4

Knowing the syllable length was important as thus a singer knew where to add ornaments and what kinds would be suitable. Ranum even believes that singers should memorize the list in Bacilly’s treatise to be able to recognize all the long syllables in a song.

1.b) Vowels

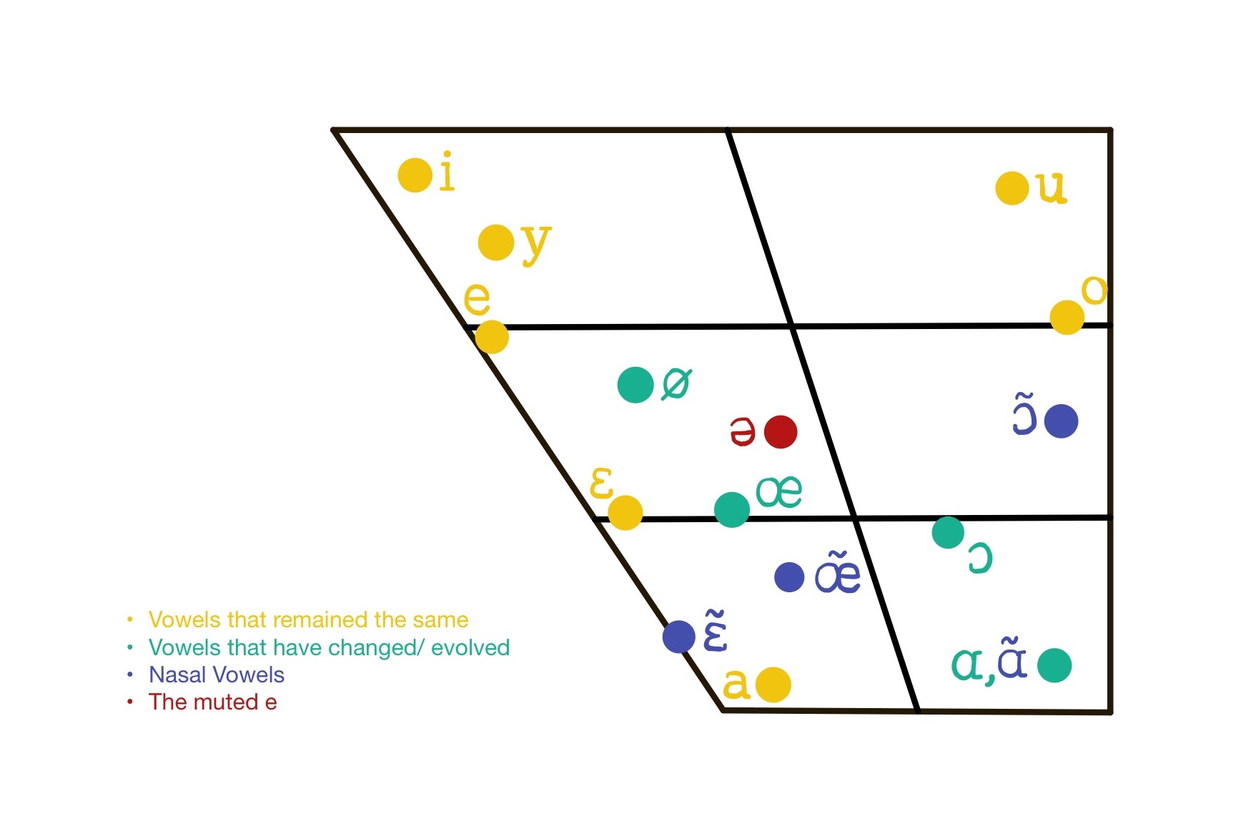

In terms of the vowels, modern French shares many similarities with 17th-century French, but at the same time, there are certain distinctions which can be noted by studying Figure 1 on the right.

The vowels /a/, /e/, /ɛ/, /i/, /y/, /o/ and /u/ remained the same since the 17th century. Bacilly’s abundant explanation of the vowel /a/ (as in part) in his treatise is rather interesting to note. He mentioned that when singing an /a/ vowel in port de voix (the French appoggiatura) and in a long note, the mouth should gradually open wider so that the tone quality gradually becomes more agreeable to the listener’s ear. In order to do this, the mouth must be open wide when singing /a/ in a passionate or sentimental phrase; moreover, the mouth must be opened in a way similar to a smile when singing with the expressions of joy.5

It should be noted that the vowel /ɑ/ did not exist in the period in question. Stewart pointed out that the tongue position of 17th-century French was generally higher than it is today, which caused some of the vowel to shift. For instance:

[ɑ] raised to [a], as in “la” instead of “âme”

[ɑ][o] became [ao], as in “aotre”

[o] often raised to [u], as in “souleil”

[wa] often raised to [wɛ], as in “joie” [zwejə]6

Three other vowels that underwent changes are /œ/ (as in malheurs), /ø/ (as in nœud) and /ɔ/ (in mort). In Bacilly’s description, the vowels /œ/ and /ø/ were not distinguished and are grouped under the diphthong /ɛu/. Further complicating things is the fact that this vowel was often pronounced incorrectly in the 17th century, and according to his description, perhaps sounded more like the closed vowel /ø/. This also aligns with what Bacilly stated:

…if the singer fails to bring the lips close enough together in pronouncing the eu, the sound will ordinarily come forth like an e alone as if the u were dropped… most singers begin the diphthong well enough, but… they don’t hold their lips together until the very end of the note and as a result, they deliver two separate pronunciations…7

An interesting difference found in the vowels is the /ɔ/. The /ɔ/ vowel existed in the 17th century, but a small /ʊ/ were inserted after it.

First, when the o is followed by an n or an m in the same syllable, one must take care to pronounce it as if there were a small u between the two letters… thus the singer must think of the words as being boune and coume rather than bonne and comme.8

The third thing to note about vowels is the /ə/ vowel, also called the ‘feminine e’ or ‘muted e’. It is the most relaxed form of vowel in phonetics and is often found in the ending of French words. In ordinary speech, it is not pronounced, but in vocal music in both centuries (17th and 21st), it is voiced. Bacilly held that the muted /ə/ has to be sung just as long as other vowels, and Stewart pointed out that /ə/ was pronounced as an articulated vowel with the tongue held higher as in peu.9 Modern pronunciation of the /ə/ in vocal music is similar, but perhaps with less emphasis.

The biggest difference is that nasal vowels /ɑ̃/, /ɛ̃/ and /ɔ̃/ did not exist in the 17th century. The vowels /ɑ/, /ɛ/ and /ɔ/ would be pronounced without nasality, and the consonant /n/ could not be pronounced until near the end of the note, especially when it was a long note. The consonant /n/ was given special treatment in Bacilly’s treatise as an exception to the rule ‘never sing through your nose’.10

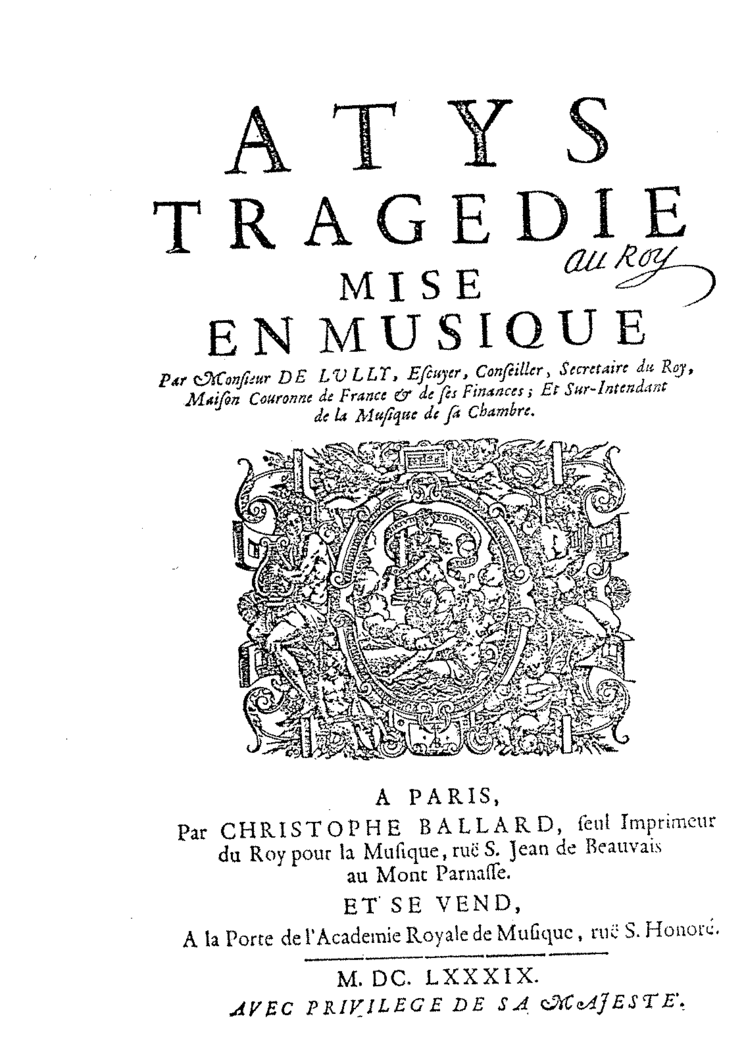

3.b) Tragédie en musique

Lully (or actually Giambattista Lulli, Florentine by birth) was also in the same performance of Ballet de la nuit, dancing next to the king. He soon became a favourite of Louis XIV and was appointed Compositeur de la Musique instrumentale de la Chambre in 1653. Lully and Quinault were significant in establishing tragédie en musique, the new style of French opera which began in the mid-late 17th century, with Cadmus (1673). The Gazette de France of 29 April 1673 described the performance as follows:

On the 27th, His Majesty, accompanied by Monsieur, Mlle and Mlle d’Orléans went to the Faubourg Saint-Germain to hear the divertissement e l’Opéra of the Académie Royale de Musique established by Sieur batiste Lully, so celebrated in this Art; the group left very satisfied with this superb spectacle in which the Tragedy of Cadmus and of Hermione, a fine work by Sieur Quinault was performed with machines and surprising decorations invented by Sieur Vigarani, gentleman of Modena.11

As opposed to Italian opera, Lully first believed that French language was unsuitable for it, therefore, he was only composing ballet de cour. Nevertheless, after he witnessed the success of Pomone (1671), he was then convinced that the future would lay in French opera rather than ballet.

After the imprisonment for debt of Pierre Perrin, Lully swiftly purchased his entire opera privilege in 1672. He achieved a monopoly of the whole Académie Royale de Musique, and with the support of Louis XIV, he obtained full control over French musical life. The collaboration of Lully and Quinault in creating an annual series of tragédies en musique dominated French stage music in this decade. Their works included: Cadmus et Hermione (1673), Alceste, ou le triomphe d’Alcide (1674), Thésée (1675), Atys (1676), Isis (1677), etc. Tragédie en musique was in fact a glorification of the monarch, and many stories, sometimes chosen by the King himself, were presented as an allegory of the royal character.

Born in Italy, Lully combined many elements of Italian music with his French music. Lully also made use of choruses which had disappeared in Italy. With the support of the King, Lully was also able to create a new instrumental ensemble for his Opéra by combining existing ensembles in the court: the Vingt-quatre Violons du Roy, the Petits Violons, the Chapelle, and the Grande Écurie.

The tragédie en musique has established the creation of French opera, and it was a significant genre for vocal music in the 17th century. As Lully had obtained absolute power over French stage music and effectively immobilized his potential rivals, the best singers in the 17th century were probably mostly involved only in Lully’s performances, singing for the king and the nobility.

Unlike nowadays, where we can get a discounted ticket and stand at the back of an opera hall, in 17th-century France, music was mostly for the happy few, people of higher social status. Performances in salons and in courtyards of hôtels were already very common in the first half of the 17th century. Only the nobility, and a few of the upper middle class were entertained. In fact, not many people owned a big court like the king, where their own prestigious weekly concerts could take place. In Louis XIV’s court at Versailles, many performers were courtiers themselves.

1.e) Jacques Brel (1929-1978)

In the CD 24 Greatest Successes published in 1988 after his death, the 20th-century French-speaking Belgian singer JacquesBrel interestingly connected his singing style to some characteristics in 17th-century French singing.

Brel demonstrated Bacilly’s special technique gronder (growling), that requires suspending a consonant before sounding a vowel to emphasize the expression of the word.12 In Ne me quitte pas, Brel suspended /k/ in quitte, /p/ in pourquoi, /k/ in cœur, /p/ in pays, /p/ in pleut, /p/ in pas… etc. In Le moribond, he suspended /t/ in je t’aimais bien, /ʃ/ in chanté, /m/ in mêmes, /ʃ/ in chagrins, /m/ in mourir… etc.

Brelalso emphasized the consonant /r/ significantly in the songLes Flamandes in words suchasrien, dire, marier, frémir, pré… etc. Interestingly, Bacilly likewise reminded singers in his time to pronounce the /r/ as clearly as possible because it was a consonant that “asks for strength and vigor”.13 Brel articulated the /r/ really clearly with strength and vigour to express his passion in the song to the Flemish girls.

In addition, Brel sang his songs with inégalité, another significant component in 17th-century French music. For instance, in J’en appelle,phrases like ‘J’en appelle aux maisons écrasées de lumière’,was sung with inégalité in almost all down beats in aux maisons, écrasées, lumière, and likewise in the next phrase ‘que chantant les rivières’.

In songs like Voir un ami pleurer, Ne me quitte pas, La valse à mille temps, he showed another typical element of French language – dynamic nuance. As French is in essence not an emotional language, there is not much dynamic changes throughout the song. The whole song was sung in similar dynamics, from mezzo piano to mezzo forte, and no significant dramatic contrast was shown.

Although the French language has gone through a great change since the 17th century, we can still trace some of the singing style in modern days. As we have seen from the example of Jacques Brel, he was still connecting some elements of French performance practice in the way he articulated French in his singing.

3. 17th-century French Performance

Vocal music in 17th-century France was often performed as part of a greater whole.

Louis XIV (1638-1715), King of France, was an accomplished dancer. In his lavish Palace of Versailles, where he compelled many a member of the nobility, he established a perfect place for court entertainments, which also contributed to a lot of the significant music making and dancing by the courtiers and the king himself. Vocal music was performed as part of the performance of ballet de cour (court ballet).

Singing in 17th-century France

This chapter aims at defining French singing in the 17th century. It will mainly focus on the language, the relationship between the language and the music, the integration of ornamentation, and the performance circumstances that inevitably affected the music of this period.

Throughout this chapter the primary references I have consulted include the 1636 treatise Harmonie universelle from Mersenne and the 1668 singing treatise from Bacilly. The contemporary references include James Anthony’s 1974 book French Baroque Music: from Beaujoyeulx to Rameau, Rebecca Stewart’s 1984 conference proceedings ‘Voice Types in Josquin’s Music’, Sally Sanford’s 1995 journal article ‘A Comparison of French and Italian Singing in the Seventeenth Century’ and Patrician Ranum 2000 book The Harmonic Orator. I have also referred to Jacques Brel’s 1988 CD recordings 24 Greatest Successes.

1. 17th-century French Language

In this section, the similarities and differences in pronunciation between modern and 17th-century French will be examined. Bacilly’s 1668 treatise will also be quoted as a representation of how 17th-century French sounded. It should be noted that Bacilly emphasized in his singing treatise the significance of a clear and detailed pronunciation in 17th-century French.

As can be observed among the majority of ill-trained singers, there are certain vocal qualities which will never sound satisfactory in themselves … and above all bad pronunciation and a lack of discernment between long and short syllables.14

Additionally, Bacilly distinguished bird song and ‘song of instruments’ from songs sung by the human voice, the latter possessing “the advantage of being able to speak”15. If the singer cannot take the advantage of singing with text, not having a thorough knowledge of the language and of the pronunciation, he is just “muted” like the other two types of songs.

Essentially, Bacilly held the view that in vocal music, simple pronunciation that could allow the audience to understand every word—clearly and without effort—was not enough, but instead the pronunciation had to be articulated with strength, weight and gravity. Thus, ‘declamation’ of the text was treasured more than singing with a pure and beautiful voice.

This style is the great favorite of those associated with the theatre; and when it is used in connection with the public speaking, it is referred to as ‘declamation.’ This latter type of pronunciation is often confused with expression and expressive speaking and singing; thus, I must emphasize that declamation is separate and distinct. I am referring only to the principal letters of the alphabet which give weight to the words which are sung and the manner of pronouncing them for this effect.16

Generally, in ordinary 17th-century spoken French, the final syllables were often dropped, but in ‘declamation’ and vocal music, all words had to be used to the greatest advantage, and an appropriate emphasis on consonants in certain words also had to be maintained.

1.a) General Characteristics

The pronunciation between modern and 17th-century French in vocal music shares some similarities as well as some differences. First of all, they both emphasise a clear and precise diction, and teachers—both then and now—use the “open-your-mouth” pedagogy.

It is a very common maxim among teachers of singing that if a person wants to sing properly, he must open his mouth. (Bacilly 1668)17

The same applies to modern times, as singing teachers often ask students to open their mouth to acquire a clearer pronunciation and delivery of vowels. Singing vowels are, in general, more open and executed with less sharpness than spoken vowels. But as Bacilly also mentioned in his 1668 treatise, it is “a great mistake not to open one’s mouth in certain situations and on certain vowels; [however] it is just as great an error to open the mouth in the wrong places.”18

In 17th-century France, closed and forward vowels like [i], [e] and [y] were actually more preferred in a musical context. For instance, according to the musicologist Rebecca Stewart, the French characterized their language as one that has “tenseness, [relative] purity, strong lip action, nasalization and a forward pronunciation with a convex position of the tongue.”19 Peter Van Heyghen also lists out some elements of the French language in the Baroque period:

· strong lip action, consonants rather soft, but important, can be lengthened (lot of air)

· constant air flow, movable tonic accent, principle of liaison, accent: pitch and length

· dynamic nuance: French is not an emotional language

· general tempo rather quick, quantitative rhythm, triple meter, hemiola, inégalité

· rich palette of timbre possibilities: many diphthongs, use of falsetto register

· preferred vowels: all closed and forward20

In the following sections, we will have a closer look on French linguistic practice during the period under discussion.

2. 17th-century French Ornamentation

Singing in 17th-century France is no easy task. Apart from singing beautifully with a clear and understandable diction, a singer was also expected to possess a flexible voice, to have all the knowledge of ornamentation and how to correctly apply them in the music, and above all, to have a good taste.

The degree of application of ornamentation varied throughout the century. As we have previously discussed, in the early years of the 17th century, aesthetic tastes turned from the complex polyphonic texture to simple solo songs, abandoning performances that obscure the clear delivery of text. As described by Shrock, in the first decades of the century, ornamentation was generally excluded from the performance of recitatives. Improvisatory ornamentation was simple. By the second and third decades of the century, ornamentation expanded in its frequency of application, and by the middle of the century, ornamentation was a substantial factor even in recitatives.

Mersenne provided an insight for us on how French vocal ornamentation was taught and practiced in the fourth decade of the century:

Now after one has taught the singer to form the tone and adjust the voice to all kinds of sounds, one trains him to make embellishments, which consists of roulades of the throat, corresponding to the shakes and accents that are made on the keyboard of the organ and harpsichord, and on the lute and other stringed instruments…

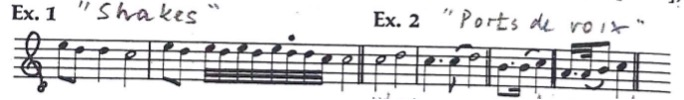

…if the cadence is composed of three notes, la, sol, fa, one should place the shake on the sol, making 4, 8, 16, or as many repercussions as one can or wishes on la sol, la sol, la sol, etc., as one sees in the following example,

After one has learned to make these ornaments, which can be used for all kinds of passages, he should learn to perform ports de voix [appoggiaturas], which make songs and recitatives most attractive… But these ports de voix are not marked in the printed books; this one can do by putting a little dot after the note on which one begins the portamento and then adding a quarter or eighth, or sixteenth after the dot… This should only be done where it is most suitable and in places where the ports de voix have some grace; and one can draw the same conclusion in regard to the trills, roulades, accents, shakes, and decrescendos of the throat and voice. (Mersenne 1636)21

Later, in Bacilly’s time, French ornamentation was even more widespread and was criticised when omitted in a performance:

Without any doubt a piece of music can be beautiful, but at the same time unpleasant. This is usually a result of the omission of the necessary ornaments. The majority of these ornaments are never printed in the music, either because they cannot accurately be produced to print due to a lack of appropriate musical symbols, or because it may be thought that a super-abundance of markings might hinder and obscure the clarity of an air and thus result in musical confusion.22

As discussed in the previous section ‘Notation and Improvisation’, and in the quote by Bacilly above, ornaments would never be printed in the music, but they needed to be executed in a performance, at least starting from the middle of the 17th century. It would be a big fault for singers in this period to omit ornaments singing a French air, since this was an essential innovative duty of the performer.

It is a tradition of long standing not to print all the necessary vocal nuances in the first couplet of an air, but to leave the interpretation up to the individual style of each singer.23

In the next section we will further discuss what defined French vocal ornamentation in the 17th century.

2.a) Agréments

The practice of enriching a score with ornamentation was prevalent throughout the Baroque era in Europe, but there were some characteristics that can distinguish agréments (French ornaments) from other nations’ ornaments. Generally, as pointed out by Shrock, the addition of passaggi (melodic passages) was widespread in Italy, while single-note ornaments such as trills and mordents were more commonplace in France. In Germany and England, passaggiwere added to solo compositions and appoggiaturas and trills were added to choral and orchestral music.24 To know the appropriate ornaments needed in a performance, it is important to know the national customs that the composer had in mind when composing the music.

Bacilly listed the vocal ornamentswhich were ordinarily never printed in music:

1. port de voix

2. cadence (as distinguished from the ordinarytremblement)

3. double cadence

4. demi-tremblement (also called thetremblement etouffé)

5. soûtien de la voix

6. expression (calledpassionner by the commoners)

7. animer

8. accent or aspiration

9. diminution

A selection of these French vocal ornaments will be further discussed in detail later (‘List of French Vocal Ornaments (1650-1750)’). Since these vocal ornaments were not printed in music, it was up to the singer to interpret when and where to apply them. Then, how optional was ornamentation in 17th-century French vocal music? How much liberty did singers have in their interpretations?

The French air de cour was a popular style of composition in this period. This simple and transparent style of solo vocal music, which consisted of a solo voice with a simple chord-producing accompaniment, was composed of two verses. The first verse is usually performed with the plain melody with certain simple agréments, whereas the second verse, commonly called the double, is expected to be embellished with elaborative ornaments.25 In the double, the metrical structure can even be altered according to the expression of the singer and their taste of adding agréments.

Moreover, I don’t want to forget to mention that it is entirely inappropriate to find fault with the singers of these little airs when they take certain liberties with the structure of the music in order to make them more tender. For example, they often slow down the tempo in order to give themselves time to add agréments which they feel to be appropriate and at times they will even break the metrical structure… It is completely unfair to criticize this style of performing by saying that the air aren’t danceable, as thousands of ignoramuses have done. If this were to be the intention of the performing singer, then his function would be no more than that of a viol. (Bacilly 1668)x

Therefore, ornamentation was not a choice, nor merely a decoration in 17th-century French vocal music. It was a necessity. There was a great liberty for singers to add agréments,but it was absolutely necessary to embellish the double of air de cour. However, it is also important to note that ill-placed, exaggerated applications of ornaments could also be considered abusive. In the next section we will discuss what are the criteria to integrate ornaments in a French air.

1.c) Diphthongs

Another types of French vowels are their diphthongs. I have summarized the main diphthongs described in Bacilly’s treatise and compared them in Table 1 to modern French:

|

Written |

17th-century French |

Modern French |

|

ie |

/i/ |

/i/ |

|

ai |

/e/ or /ɛ/ |

/e/ or /ɛ/ |

|

au |

/o/ |

/o/ |

|

ay |

/e/ or between /a/ and /e/ |

/e/ |

|

œ |

/ɛu/ |

/ø/ or /œ/ |

|

ou |

/u/ |

/u/ |

|

oi |

/wɛ/ |

/wa/ |

Table 1: A comparison between diphthongs in 17th-century and modern French

There are two main diphthongs that were pronounced in a different way in the 17th century: ‘œ’ (discussed in the previous section ‘Vowels’) and ‘oi’.

The vowel ‘oi’ or ‘oy’ was described as “the most embarrassing one in all of French vocal music”.26 In Bacilly’s description, this vowel is pronounced with two successive sounds: o (almost an ou) and following by a wide-open e, thus it would sound like ou-ai or /wɛ/. It is quite different from the modern pronunciation /wa/.

1.d) Consonants

In terms of consonants, they are more stressed and explosive in singing than in speaking in both 17th-century and modern French.

If your listeners cannot understand the words you are singing, they will often feel embarrassed and uncomfortable toward to vocal ornaments. … In short: singers must always be apprehensive about not pronouncing their words well enough. (Bacilly 1668)27

French consonants did not undergo as much alternations as French vowels since the 17th century. The strong lip actions, emphasis on consonants, the elision of final consonants to the word beginning with a vowel, and the overall rhythm of the language remained basically the same. However, one obvious change was the drop of final consonants in modern French.

There were several things that Bacilly emphasized that are worth noting also for modern singers. The consonant /r/, in Bacilly’s description, that “asks for strength and vigor”28, must always be pronounced clearly, especially when it was preceding another consonant like in parfait, pourquoy (pourquoi). Stewart has a similar view that “the /r/ was rolled very markedly at the beginning of a word, or when it preceded or followed another consonant.”29

The consonant /l/ must be pronounced solidly as well, even in a monosyllable like il. The consonant /n/ had to be treated with caresses and gentility, unlike the above two consonants, and as mentioned previously in the section about nasal vowels, the /n/ must be pronounced only at the end of the note. Also, the aspirated /h/ was pronounced much more than in modern French.30

A special technique called gronder is suggested by Bacilly that allowed suspension of a consonant before sounding the following vowel.31 A good example is the consonant /m/. In words like mourir, malheureux, misérable, lengthening the consonant /m/ could create a suspension and tension, and thus give a greater strength of expression to the words. This also applies to other consonants like /f/, /n/, /s/, /dʒ/ and /v/, only when they are not between two vowels.

The most significant difference between 17th-century and modern French consonants is the pronunciation of the final consonants. Most final consonants in French are silent now, only /r/ and /l/ are still pronounced among the few final consonants. In Bacilly’s treatise, we can tell that in ordinary speech, people were already dropping some of the final consonants, but in vocal music, he insisted that it was obligatory to pronounce the final /s/, /t/, /l/ and /k/, and that is essential to the proper understanding of the text. The final /s/ could only be dropped when it was not necessary to distinguish the plural from the singular, and when it was followed by a consonant in the middle of a sentence. Nonetheless, the final judge of when to pronounce a final consonant must be le bon goût (good taste).

In all cases the meaning of the word is a more important consideration than the grammatical rules. (Bacilly 1668)32

I have stated the major rules in pronouncing 17th-century French and how it was different from modern French. There were more exceptions listed in Bacilly’s treatise, but as he pointed out, the meaning of the word had the most significance and should be considered before the rules. It was most essential to deliver the meaning of the text to the listeners.

In addition to the linguistic aspects, there are a number of characteristics in 17th-century French singing style listed by Van Heyghen33 mentioned earlier in this chapter that were not discussed in detail, because they were not essential in this research topic. For example, the dynamic nuances, the inégalité, and the use of falsetto register. However, some of these characteristics will be briefly mentioned in the review of Jacques Brel’s recording below.

3.a) Ballet de cour

Ballet de cour was a significant French court entertainment during the 17th century. It all began on the evening of 15 October 1581, at 10pm to 3.30am, when Circé ou le Balet comique de la Royne was performed at the Petit Bourbon palace in Paris.34 Circé is believed to be the earliest ballet de cour and was “the first attempt in France to unify poetry, dance, music and décor within one continuous action”x. Born in Italy in the traditions of the spectacular intermedi and balletti a cavallo, the ballet de cour soon found its popularity because the French were natural dance lovers. Even the king himself, Louis XIII, composed a ballet de cour – Ballet de la Merlaison (1635).35

Components of a typical 17th-century ballet de cour include: récits, vers, entrées, and usually a concluding grand ballet. The récits, which means ‘sung by only one voice’, were generally found at the start of each act of the ballet, and it was the main part of vocal music in this genre. They were often performed by characters who did not dance, and were often very similar to airs de cour, helping to mark the act. The vers were texts written by poets that were provided in livrets as a reference to spectators. The entrées were elaborately costumed and masked dances, that separated the acts into scenes. The grand ballet was the finale of the performance and was danced by the grands seigneurs and sometimes also by the king himself. This was often the result of the large collaboration of a royal patron, including poets for vers and récits, two or more composers for the vocal and instrumental music, and a machinist for the stage management.36

In the middle of the 17th century, during the early part of Louis XIV’s reign, the ordonnateur des divertissements of the court, Isaac de Benserade, started to renew the ballet de cour by involving just one composer and one librettist in a work, instead of the large collaboration mentioned above. He started his revival with the Ballet de Casandre (1651), then when he found his best colleague, Jean-Baptiste Lully (1632 – 1687), they first produced Ballet de la nuit (1653), and then over 20 works of ballet de cour together.37 The king, Louis XIV, was also enthusiastic in participating in ballets de cour. He danced for the first time in Ballet de Casandre, and because of his performance as the ‘rising sun’ later in Ballet de la nuit, he was recognized as the ‘Roi Soleil’ ever since.38

Ballet de cour remained popular until 1670, when other genres slowly took over its popularity. Nonetheless, the influence of ballet de cour remained crucial on the development of French opera until the 19th century.

2.c) Disposition

Apart from all the rules and knowledges that we could learn from book and doctrines, there was also an important yet not so common ‘gift of nature’ that Bacilly believed a singer had to possess to perform ornaments well, and that was disposition, the ability to sing pleasantly and to move the voice with speed and agility.

The throat must be so well-disposed by nature that the singer is able to sing a piece pleasantly and according to the rules in a very short time and with almost no training, so that the listener has a good reason to be confused about how long the singer has studied.39

Bacilly thought that it was very rare for a throat to be suitable in singing all types of agréments, just as a voice could not be suitable in singing all types of voice parts. Some singers could do better in passages and diminutions, while others could perform better in accents and aspirations.

In conclusion, singing in the 17th century involved learning all the “new” styles of agréments, composing the double with one’s interpretation, adding ornaments to the right cadences and right syllables, and being able to sing pleasantly amidst all the different types of ornamentation.