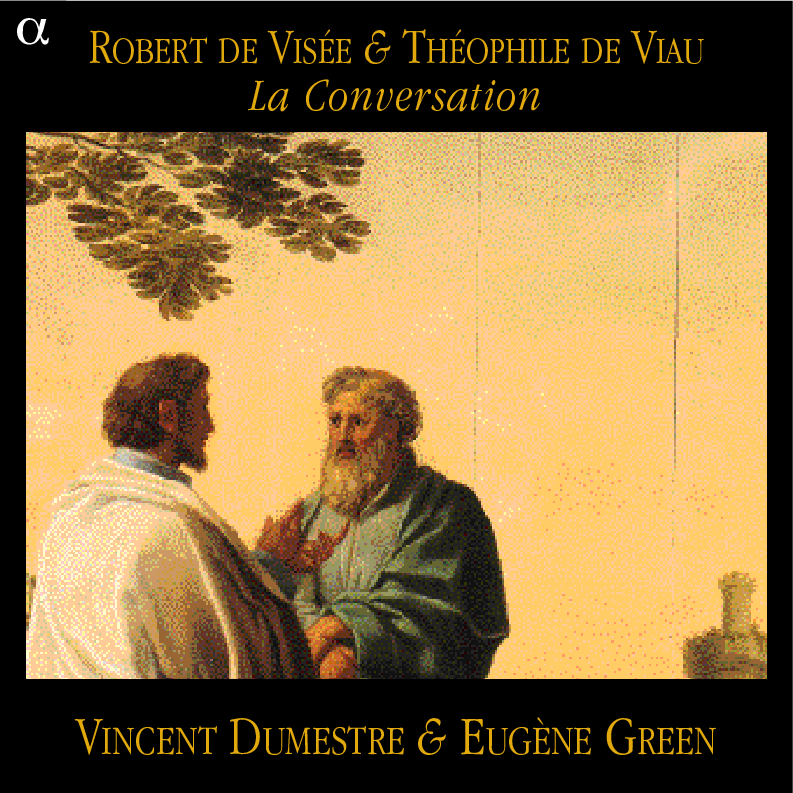

De Visée & De Viau : La Conversation

La Conversation consists of CD recordings of poems by Theophile de Viau (1590 – 1626) declaimed by Eugène Green in Old French pronunciation, and lute works by Robert de Visée (ca. 1650 – 1725) performed by Vincent Dumestre on the theorbo, recorded in France in September 1998 and released in 1999 by Alpha 003.

Poems by Theophile de Viau are very dramatic, intense and full of passions, because he himself is a tragic figure. The talented poet de Viau was a member of the minor nobility and entered the service of the Duke of Montmorency. However, during the Wars of Religion, his hometown was destroyed, and he was accused of atheism, blasphemy and debauchery with women and boys by a witness corrupted by his Jesuit enemies. De Viau was imprisoned and was sentenced to death. Although he was pardoned eventually, he died soon after that because of his broken health at the age of thirty-six. Some of his poems recorded in the CD were written when he was in the prison and when his hometown was destroyed.1

This review will focus on the poems by Theophile de Viau declaimed in Old French pronunciation by Eugène Green. As discussed in previous chapters, declamation was on par with vocal music in the 17th century, because of their similarity in nature and their aims – to deliver the text with clarity. Techniques used in declamation can also be applied to singing, therefore, this review will be of great importance for modern singers to learn about expressing the text even without music. The pronunciation, the tempo, the dynamics of the declamation, and how Green made use of different means to express the ‘passion’ in the text will be explored.

In general, Green declaims the text in a slow tempo with clear consonants and vowels of the Old French. He has strong lip action, tenseness in delivery, and a clear forward pronunciation, which are very similar to the descriptions of 17th-century French pronunciation by Rebecca Stewart2 and Peter Van Heyghen3. To emphasize a word, he does it by strengthening the pronunciation of the consonants and lengthening the vowels. Dynamic change is not often, but when used, is very exaggerated. Tempo is in general very slow, but sometimes accelerated for expressive purposes. These will be discussed in detail in the following sections.

Conclusion

Eugène Green declaimed Theophile de Viau’s expressive poems with his knowledge of the Old French and his interpretation of the passions conveyed in the text. Green’s vowel pronunciation is partly in line with and partly not with what Bacilly described in his 1668 singing treatise, but his pronunciation of the consonants, in my opinion, is impeccable and very clear. Green made use of different rhetoric techniques to enliven his declamation, such as dynamic contrasts, change of tempo, diverse tone colours, different lengths of vowels and gronder (suspension) of consonants. These rhetoric techniques can inspire modern singers on how to express the different states of emotions in order to “stir the human passions” like an orator.

Part Three: Recording Review

This chapter will consist of an in-depth review of the following recordings in their approach to 17th-century French declamation and singing.

Vowel pronunciation

Based on the previous chapter about French vowel pronunciation in Part Two of this research, it was discussed that the vowel /ɑ/ did not exist in the 17th century because the tongue position was generally higher than it is today. Green’s declamation has not taken this into account. In the Sonnet Sacrez murs du Soleil, Green pronounces âme as /ɑm/, which is different from his /a/ in sacrez, adoray and charmée. In Quand tu me vois baiser tes bras, Green pronounces bras as /brɑs/ and draps as /dras/.

The vowels /œ/ and /ø/ were pronounced in the 17th century like the diphthong /ɛu/, but Green chooses to pronounce orgueilleuse as /ɔʀɡøjø/ in the Sonnet Sacrez murs du Soleil. Also, in Quand tu me vois baiser tes bras, we can hear a clear closed and forward /ø/ in cieux, yeux and peux.

Bacilly mentioned that the vowel /ɔ/ was pronounced with a small /ʊ/ inserted after when followed by an /n/ or /m/4. Green pronounces hommes /ɔməs/ in Sacrez murs du Soleil, comme /kɔmə/, sommeil /sɔmɛj/ and donnant /dɔnan/ in Quand tu me vois baiser tes bras without an /ʊ/ in between.

Although Green did not declaim the vowels /ɑ/, /œ/, /ø/ and /ɔ/ like what we have discussed earlier, he has demonstrated very clearly the old French without the nasal vowels /ɑ̃/, /ɛ̃/ and /ɔ̃/. In Sacrez murs du Soleil, Green pronounces the /n/ separately form the vowels in mon, sanglant, ornemens, grand, ensemble, combine… etc. In Quand tu me vois baiser tes bras, the words quand, bien, main, sein, son, ardans, dans, ton are also pronounced without nasality and the consonant /n/ is clearly pronounced at the end of these words.

Green pronounces the diphthong ‘oi’ or ‘oy’ as /wɛ/ in 17th-century French instead of /wa/ in Modern French. Examples can be found in Quand tu me vois baiser tes bras, where he pronounces vois as /vwɛ/, toy as /twɛ/, avoir as /avwɛr/, voir as /vwɛr/ and quoy as /kwɛ/.

The final note about vowels is that Green does not pronounce every vowel with the same length. He noticeably stretches certain vowels in order to give stress to a word, or because they are diphthongs or long vowels. For example, in the first verse of Sacrez murs du Soleil, he stretches the vowels underlined in the following:

Sacrez murs du Soleil où j'adorai Philis,

Doux séjour où mon âme étoit jadis charmée,

Qui n'est plus aujourd'hui soubs nos toits démolis

Que le sanglant butin d'une orgueilleuse armée;

Translation:

Sacred walls of the Sun where I adored Philis,

Sweet abode where my soul was once charmed,

Which is no longer today under our demolished roofs,

Than the bloody spoils of a proud army.

Consonant Pronunciation

Green puts a lot of emphasis on consonants in his declamation with his strong lip action, his lengthening of the fricatives, such as /s/, /f/, /v/, /ʒ/ and /ʃ/, and with his prominent elision of the final consonants. Bacilly emphasized that the consonant /r/ asked for strength and vigor 5, and the way Green does with the /r/ is impeccable. The /r/, when in the beginning of a word, preceding or followed another consonant, is pronounced with more vivacity by Green. For instance, in Sacrez murs du Soleil, the /r/ in sacrez, murs, charmée, armée, grand, ruiné, effroyables, larges, creux, frayeur, cris, charniers, Corbeaux, repaistre, naistre is exceptionally vigorous as compared to in adoray, murailles and funérailles. In addition, in words like courir and mourir, even the final /r/ is not preceded by a consonant, Green pronounces it remarkably clear.

The consonant /l/ is also very solidly pronounced by Green in the same sonnet in words like l’autel, larges, combles, Philis, ensemble, ensevelis, loups, and helas. In particular, the aspirated /h/ in helas is very exaggeratedly pronounced with a lot of air.

Green uses the technique gronder suggested by Bacilly that allows a suspension of a consonant before sounding a vowel. Examples from the same sonnet Sacrez murs du Soleil are /s/ in Soleil, /f/ in Philis, faictes, frayeur and fois, /ʃ/ in charmée, /s/ in sangalnt, /m/ in m’avez and mourir.

In contrast to the Modern French, all the final consonants in 17th-century French were pronounced unless it is followed by another consonant in the middle of the sentence, and not before a comma. Therefore, Green pronounces the final /s/ in desmolis, abolish, palais, hommes, chevaux, ensevelis, murailles, funérailles and fois, and the final /ə/ prominently in charmée, armée, fumée, allumée, repaistre and naistre.

Expression

Van Heyghen stated that French is not essentially an emotional language, and that dynamic contrast is not a primary characteristic of the French language.6 This is generally applicable to Green’s declamation, as his performance is largely in a mezzo forte with little dynamic change. Nonetheless, in some of the recordings, Green makes use of dynamic change for his intense expression.

In Je songeois que Phillis, the licentious sonnet which gave rise to the plot against Viau7, Green declaimed some of the lines with extreme dynamic changes. Green uses a higher tone to portray the speech of the deceased lover Phillis, and as the poem comes to an end, Green declaims it in fortissimo, full of power and strength when declaiming the moment Phillis farewells Tirsis. The following shows the relative increase in dynamics with the relative increase in font size:

Elle me dit: Adieu, je m’en vais chez les morts,

Comme tu t’es vanté d’avoir foutu mon corps,

Tu te pourras vanter d’avoir foutu mon âme !

Translation:

She said to me: “Goodbye, I am going to the dead,

As you bragged about having screwed my body,

You can brag about having screwed my soul!”

Van Heyghen also stated that the general tempo of French language is rather quick. However, in Green’s interpretation of the declamation, he does it in a slow tempo, perhaps also due to his intention in portraying the 17th-century stage performance, which is different from the everyday language. As Dumestre put, “Twentieth-century artists seek naturalness, where the seventeenth-century artist sought artificiality in the etymological sense of the word (from the Latin ars, art and facere, to make): made with art.”8

Yet, Green does not stay in the same tempo throughout his declamation. He utilizes the change of tempo from time to time to stir the listeners’ passions. In the Ode Un corbeau devant moi, we hear a lot of change of colours and tones of his voice, and the tempo varies as well. The distribution of the text below briefly shows how Green interprets the tempo of the poem (the more condensed the text, the faster the tempo):

Un Corbeau devant moi croasse,

Uneombre offusque mes regards

Deux belettes et deux renards,

Traversent l'endroit où jepasse :

Les pieds faillent à mon cheval,

Mon laquais tombe du haut mal,

J'entends craqueter le tonnerre,

Un esprit se présente à moi,

J'ois Charon qui m'appelle à soi,

Je vois le centre de la terre.

Translation:

A Crow in front of me croaks,

A shadow offends my eyes,

Two weasels and two foxes

Cross the place where I pass:

My horse's feet fail,

My lackey falls from the top badly,

I hear the thunder crackle,

A spirit presents itself to me,

I am Charon who calls me to himself,

I see the centre of the earth.

De Visée & De Viau: La Conversation – CD Booklet9