I have a vague memory that I began this project in the middle of a Zoom meeting. There were so many. As the lockdown took hold and we entered Quarantine Time (the months of Q.T.) — a bizarrely featureless interregnum — I punctuated my days with planning meetings, class sessions, and eventually webinars and various kinds of conversations. If this origin story is accurate, I most likely first drew during a Zoom session in which I was not participating actively, yet was still listening. Awash in language. Distracted by worries. Seeking ventilation. Thoughts about basic administrative tasks, such as figuring out how to get groceries, and how to assess danger levels (would marauders start coming to the door with guns, demanding food?), buzzed in my mind like the hum of voices coming from the Zoom meeting.

I reached for a nearby scratch pad and quickly wrote out my most pressing thoughts. The words filled the small page, and I paused. I had crafted a paragraph. Then I realized that I had more to say, so I wrote in the same space of the page — this second paragraph got interlineated with the first. A reader fresh to the page would not be able to make sense of the text.

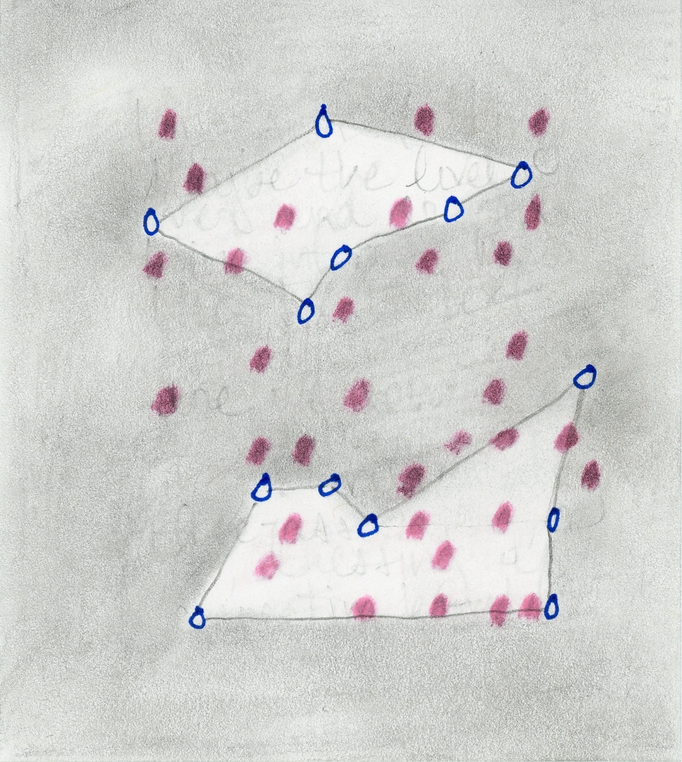

Looking at the page of handwriting that I had already transformed into nonsense, I sought to make it even less legible. I found and articulated salient forms, and colored around the lines like in a coloring book. I did not feel it necessary or desirable to make the contents of my thoughts available to others. This was not just to honor a wish for privacy, but to acknowledge that so many thoughts go by in any given moment, unrecorded and unremarked. Once I derived a visual pattern from the text, I no longer needed to see the words anyway. So I erased them. They had done their job, giving me a glimmer of reprieve and providing the basis for a drawing.

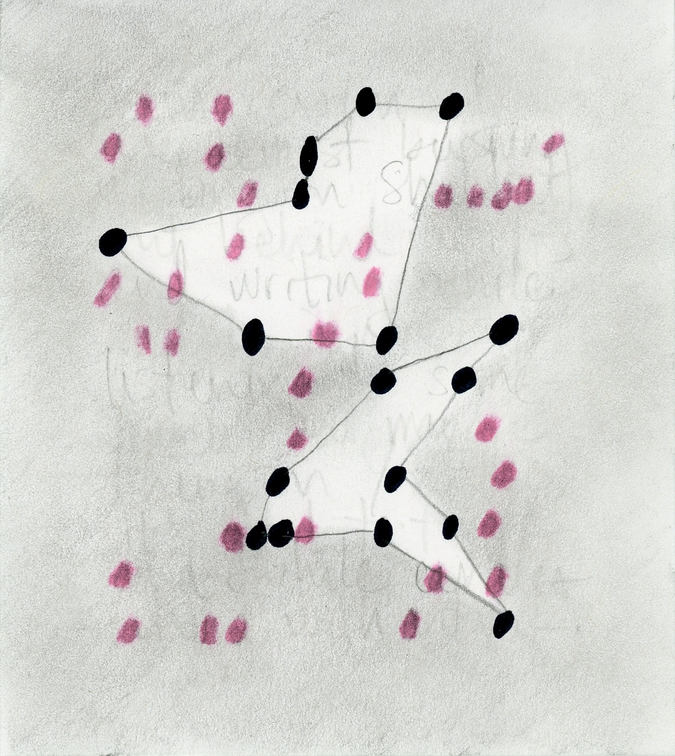

I am sure that I started the project after I started going outside for walks. There is a walking trail near where I lived then, so I would venture out. I was elated to be in the presence of other human beings on the trail, yet proximity made me wary. Were they lethal? We sized each other up, as if we would be able to detect outward signs of safety or contagiousness.

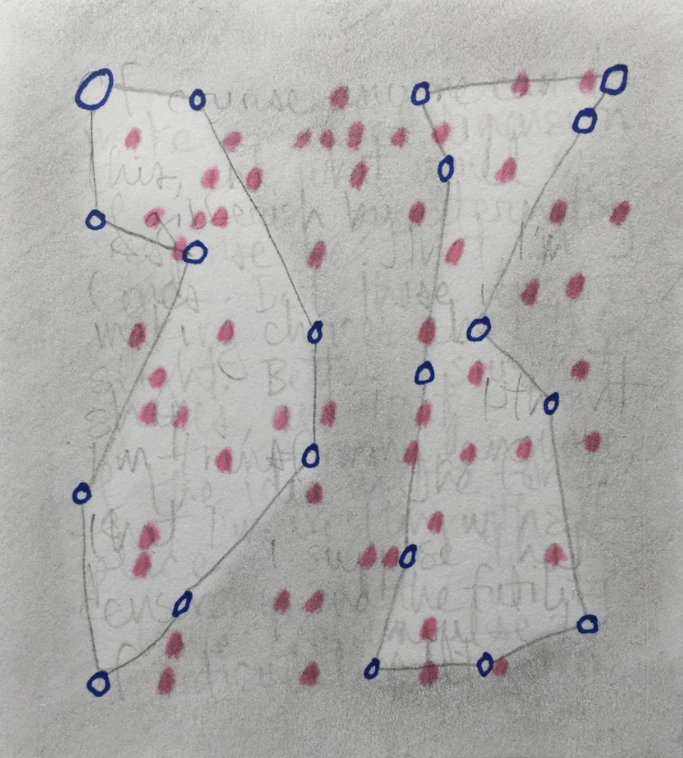

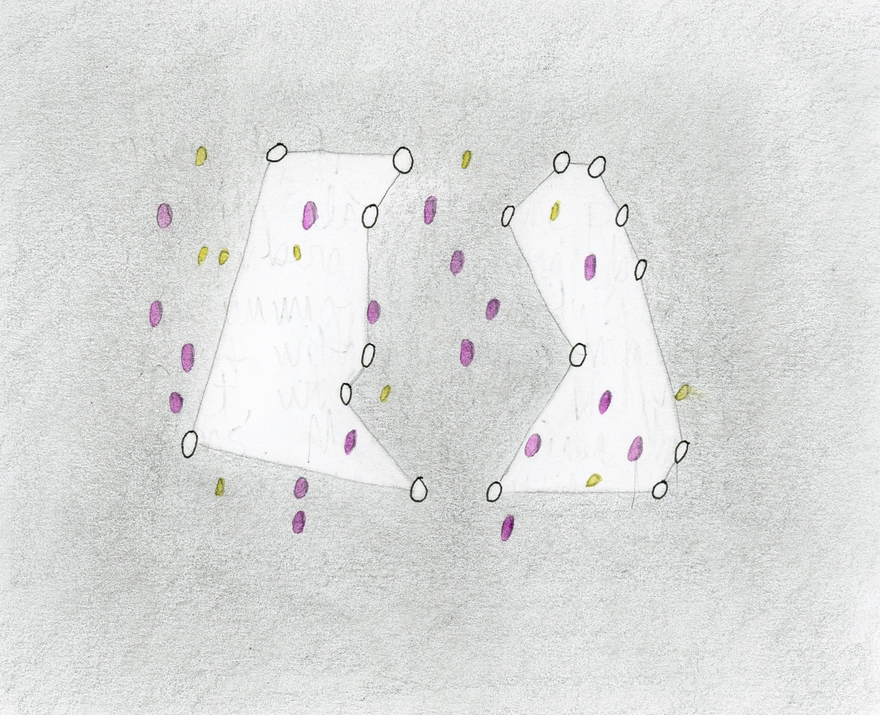

Back at my desk, coloring in the counters to the letters “a,” “b,” “d,” “g,” “o,” “p,” and “q” was a soothing way to doodle. A manageable task, when so much felt overwhelming. Yet the results of this process got me interested in what the page looked like, so that I shifted from doodling into drawing. (When does a distraction become an action?)

The color palette initially came from the markers that happened to be in front of me, in a coffee mug of writing tools. The pink highlighter proved symbolic: it made the dots look like mosquito bites. Perhaps the association with this minor medical malady prompted me to connect the drawing’s imagery with the consequential medical malady of the virus.

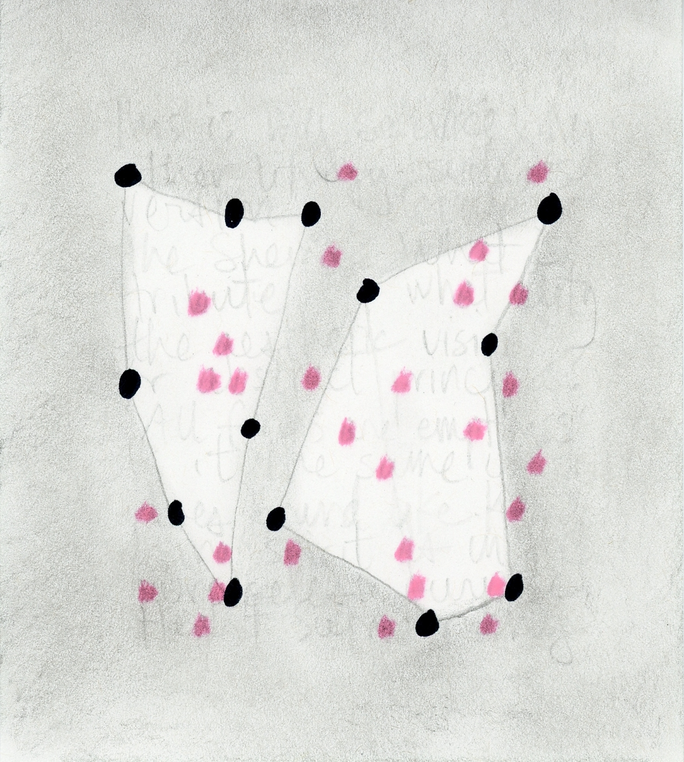

It was the shapes that emerged from this process, however, which provided the conscious basis for the comparison. After I erased the underlying text, I “connected the dots” of, first, all the Os. These transformed the arrays into coherent, still energetic formal shapes. Many dots remained in the spaces inside and outside of the polygons. While I looked at the shapes as they occupied the pages and related to each other, they reminded me of the ways we walkers danced around each other on the path. Spiky in our watchfulness, we said “Hello” yet kept our distance. This felt like more than just the idea of giving each other “elbow room.” We were all elbows.

The dimensions of the page are like the talk therapist’s fifty-minute hour. The constraint encourages a process of taking shape, a structuring of whatever takes place within. Language coalesces into a beginning, middle, and end. In these snippets of journal writing, I began with an inchoate impulse, worked through some details, and invariably arrived at some unexpected insight. While these were not epiphanic or consequential, they soothed the agitation, imparted hope. The tangles of language externalized the mental scramble and created a feeling of aerating my internal “head space.”

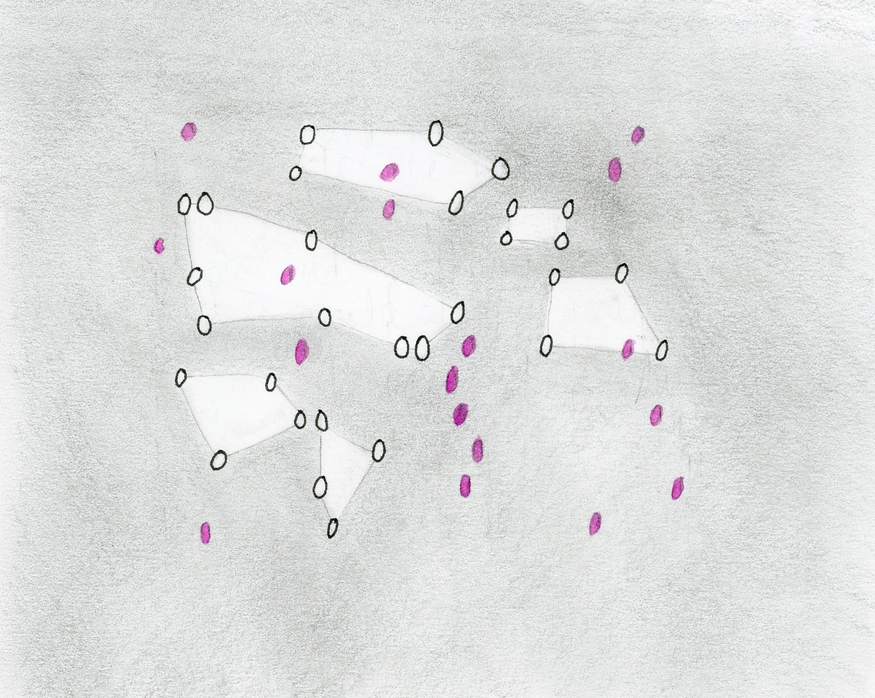

Soon I also began to see the pink dots in the drawings as thematically connected to COVID-19. These dots were hovering in

the space, inside and outside of the polygons, like how I imagined particles of coronavirus could be permeating our bodies and the air surrounding them. On my walks, I had started to regard every passing person like an embodiment of Pig-pen, a character from Charles Schulz’s famous “Peanuts” cartoons. Just as Pig-pen is surrounded by specks of dirt, each of us is always surrounded by an invisible cloud of microbes. Perhaps our bodies could also be considered as clouds of microbes, just more densely packed?

I realized that these analogies applied to the coronavirus. Pigpen could be breathing in the surrounding dirt, and likewise the virus particles could be passing from the air into or through our bodies. Such exposure would not necessarily cause sickness; transmission need not mean contagion. The virus potentially could touch us physically without touching us consequentially. In April and May, we were learning that some people could be drastically affected by the virus, others could carry it asymptomatically, and still others could be exposed to it without contracting COVID-19 or becoming carriers. How could we assess the power of this particle?

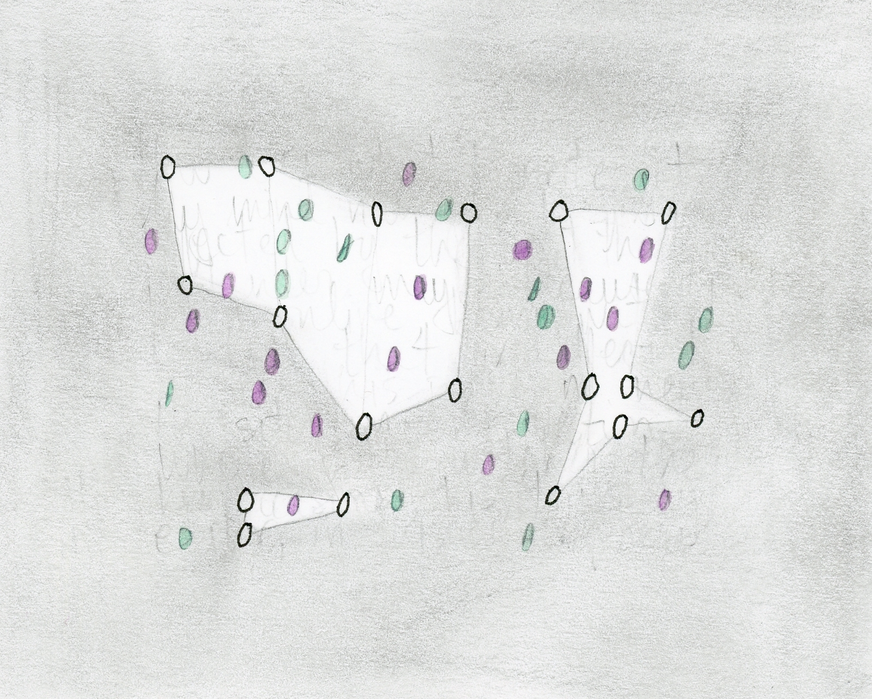

I began to play with the drawings. I started to annotate only the vowels with counters — “a,” “e,” and “o.” Linguistically, vowels give to utterances sonic “color” akin to how I was giving the drawing visual “resonance” by filling in specific letters. As I worked, I was amused by the shapes and their interactions, which thankfully gave me access to emotional options aside from the malady-anxieties suggested by the pink dots. How else could I use the drawings to gain distance from thinking always, always, always about the virus?

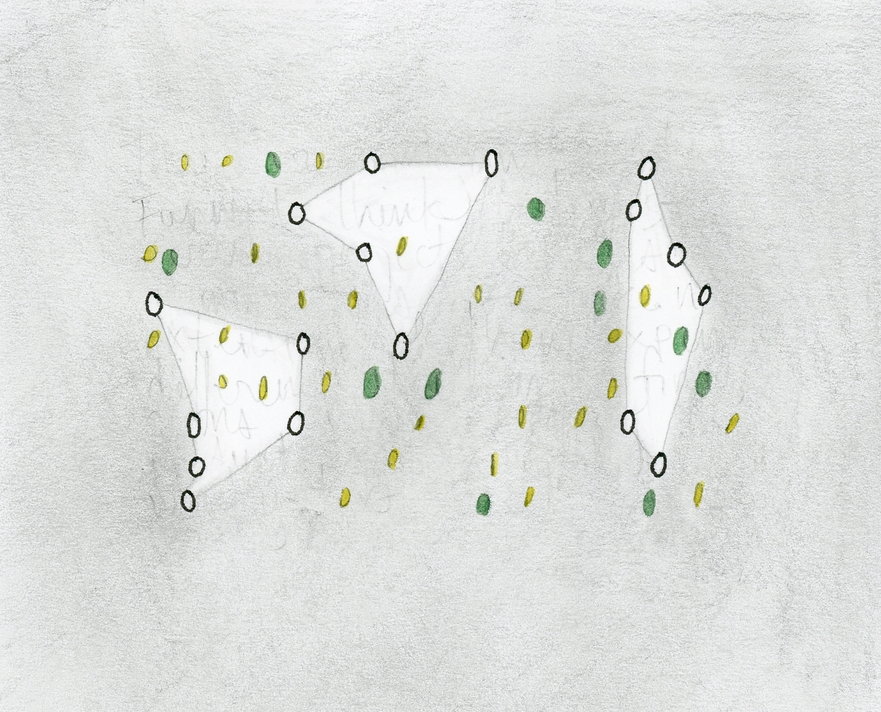

Eventually I arrived at a palette of green and gold, which has long been part of the branding of the Hamden, Connecticut hometown where I was hunkering down. This enabled me to think of the drawings as representing the experience of being amidst the sociopolitical situation, or immersed in the goings-on of life in general, without having the dots signify only the virus. These new colors looked to me like a green meadow with yellow wildflowers such as dandelions. This pastoral scene was pleasant to imagine, though for someone with allergies it might be dangerous. Again, tiny particles affect different bodies differently.

Now that I had created a more or less cheerful image, I put the project aside. I had discovered that my best remedy for pandemic agitation was an aesthetic tickle.

Sometimes I try to read the words beneath the drawings, to regain contact with the thoughts that had been significant to me in the moment. But erasing them resists the fetishization of the word, the primacy that I see attached to language in the context of (artistic) research. These words were just the residues of passing thoughts, and thoughts, after all, dissolve...

What might I generate by prioritizing the visual?