I returned to these Corona Drawings in 2021, in conjunction with proposing this exposition. This coincided with the dawning of our current epoch, the age After Vaccines (A.V.). As widespread immunization made possible a relaxing of many kinds of quarantines, I began to think of ways to expand on the drawing project. At first I intended to repeat the strategies of the earlier drawings, with more refined media and deliberate color choices, but every act of drawing made me think in fresh ways about the visual possibilities and about the transmission of ideas.

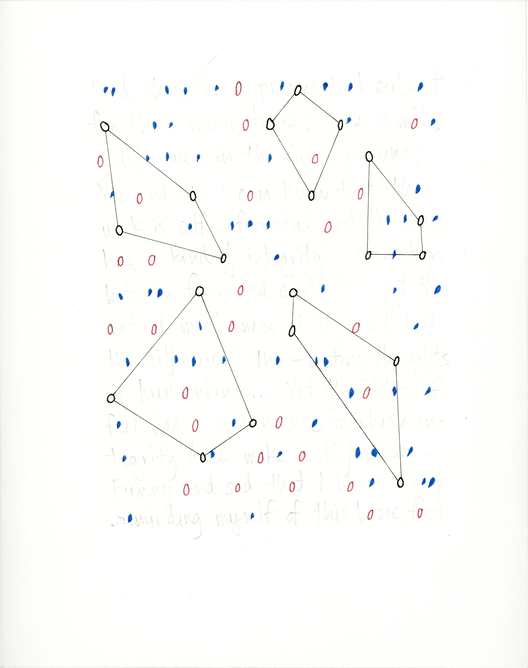

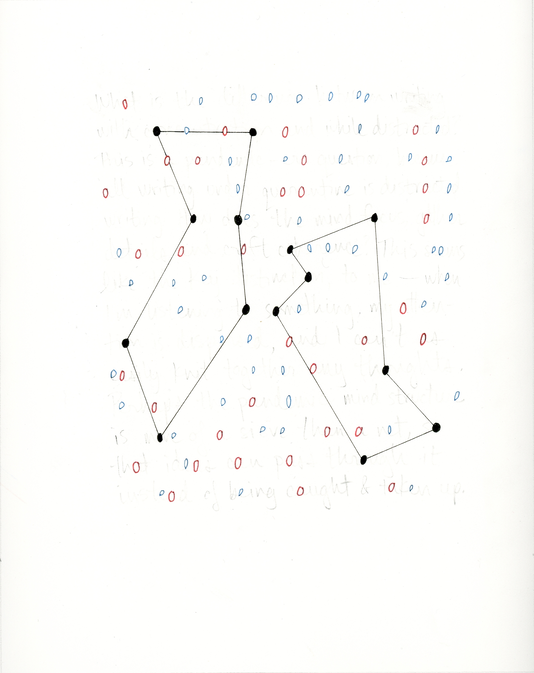

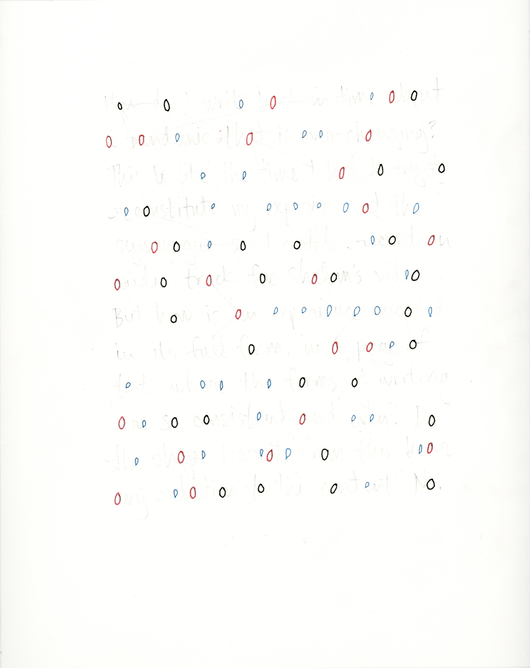

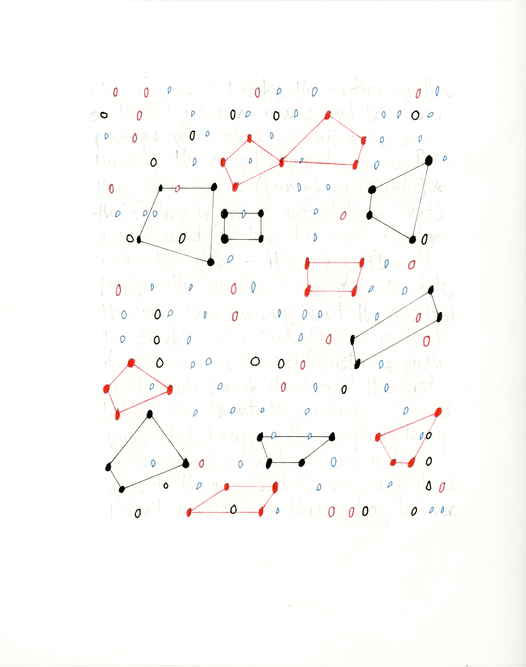

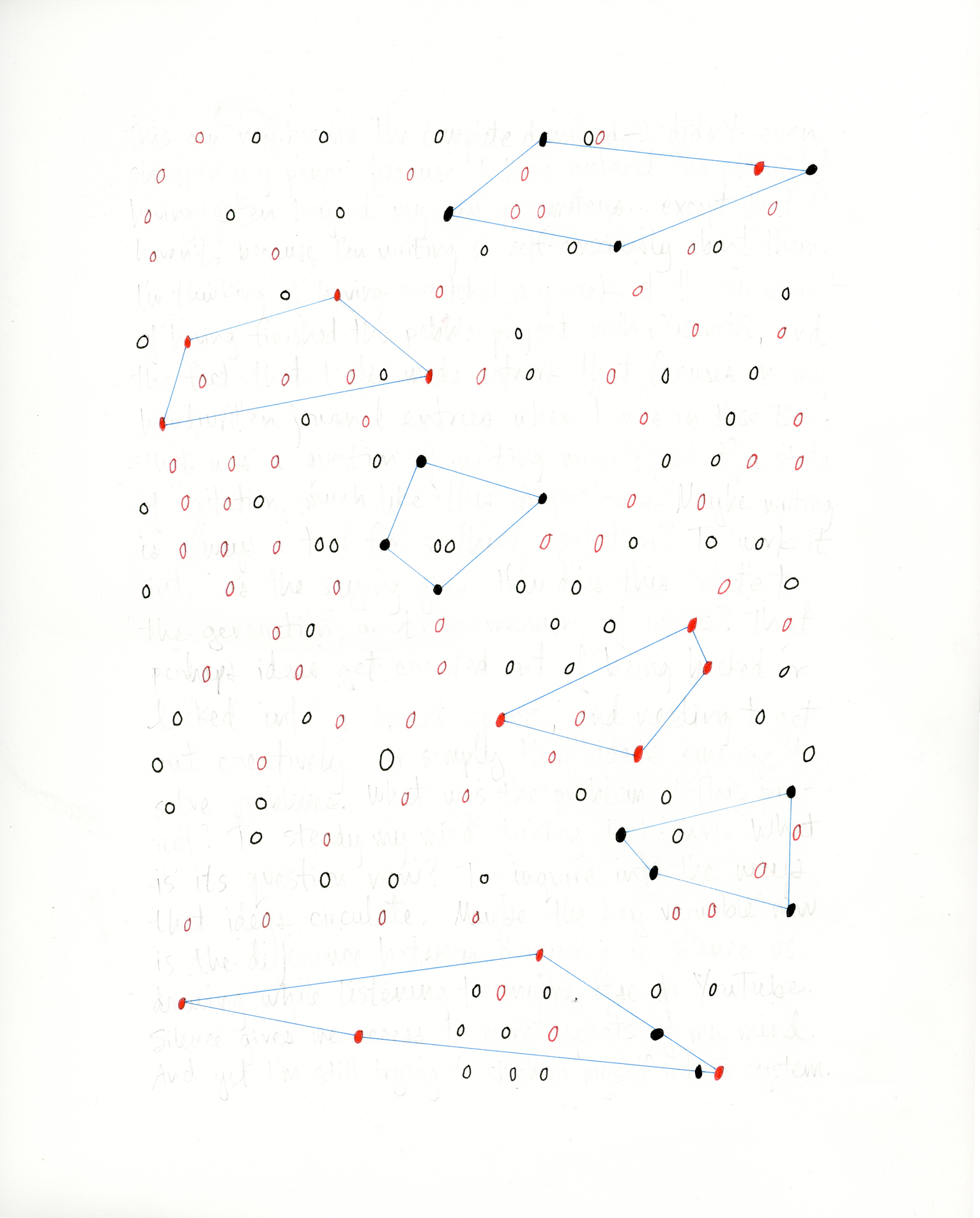

At least I shifted the formal parameters of the project, to amplify the conceptual theme. I increased the paper size to 10 x 8 inches so that these dimensions would resemble those of a piece of writing paper. And I chose a palette of black and white, red, and peacock blue. In both manuscript and print traditions, this color combination appears in the texts that have enabled the transmission of ideas. In many medieval manuscripts, bright red and lapis blue are key colors, and their electric juxtaposition conveys underlying themes that inform the texts. More recently, in graphic design layouts just before the computer era, red registered as black, and light blue registered as invisible in some photographic processes.

Even with these contrivances, the drawings consistently offered surprises. The first was that the lines of connection became optional; the drawings looked just as interesting to me without lines as they did with them. What could this imply about the transmission of ideas?

If the dots of the letters stand for ideas instead of virus particles, shapes/people can float in their midst and be affected by them even without necessarily transforming that into a conscious activity of meaning-making. Gertrude Stein theorized this type of immersion in the early twentieth century. She insisted that artists exist in a temporal, cultural milieu, so they create works that are inevitably products of their times. In “Composition As Explanation,” she proclaimed that “No one is ahead of his [sic] time… Each period of living differs from any other period of living” and that she herself was writing “entirely in accordance with my epoch.” People become temporally attuned simply by paying attention to the cultural milieu, inhaling the atmosphere of ideas.

This way of thinking is enormously abstract; even Stein admits that an “epoch” consists of “everything” that is happening in a particular time and place. The irreducibly general quality of this concept makes me turn to oceanic metaphors, and a language of fluidity. We can feel like we are swimming in the tides of ideas. What's more, we “channel-surf” on television and “web-surf” the internet. Navigation in an intellectual sea does not necessarily involve any type of teleological or “linear” thought process. From one place you can proceed in any direction. The metaphors can be airy as much as watery (to return to “inhaling the atmosphere”): the dots in my drawings can form a “cloud” of data which need not be connected by any lines.

If the dots in my images are seen not as ideas in themselves, but rather as specific data points or facts that comprise the amorphous field/sea of daily culture, then they become open to interpretation in a different way. When I create shapes from specific dots, this process of finding patterns becomes a type of knowledge production; ideas are now represented by shapes instead of dots.

Instead of conveying content, I hope that my imagery activates

the state of mind that accompanies the act of interpretation.

I emphasize the process of ideation not only by erasing the words, but by making obviously idiosyncratic shapes. The shapes may look solid, but their outlines are provisional. I could connect the same dots to form different shapes, or I could connect different dots. No consistent rules govern the process; sometimes one drawing suggests new guidelines for another. Often, I look at an array of dots/data for a long while, without a plan in mind for how to draw the lines, so that an idea can occur to me, and hopefully surprise me.

This slow examination of the visual field recalls my literary training, in which immersion in a close reading of a text could give rise to a new interpretation. But my visually oriented gloss on this semiotic field of dots suggests not close reading but rather the “distant reading” of Franco Moretti, in which taking a step back from a text and analyzing macro-patterns of data can lead to new kinds of interpretation. I sit back, soften my gaze, see what strikes my eye.

I am “reading” against cognitive logic, working visually instead of intellectually. And then my lines constitute a visual intervention.

Sometimes I try to invite possibilities by distracting my attention, for instance listening to a podcast while working. This occupies my cognition so I can indulge my visual inclinations more freely. It also revisits the experience of drawing during the height of the pandemic lockdown, almost a year before this, when my attention was distracted by consistent confusions, concerns, and input streams. Drawing, then as now, enables me to gather and organize the frayed threads of thought. In this context, we may think of the field of dots as an explosion of data into a stormcloud of disarray. Connecting them offers a more coherent, shapely alternative to a distracted state of mind. Perhaps, altogether, the contagion of ideas is triggered by the appeal that any structure offers to the consciousness. We gravitate toward the ideas that give our individual minds varieties of reassurance that we crave, forms we can inhabit.

By focusing on how the shapes instead of the dots stand for ideas, the drawings model the poetics of crafting ideas rather than of transmitting them. And just as the original drawings modeled a transmission of the virus with or without contagion, the formation

of an idea-shape does not mean that it will be considered “catchy.” The particular configuration may be powerful or attractive or not, and sometimes the shapes that I initially think of as ungainly end up being my favorites. Certainly no shape is definitive. And the field of text is perhaps strongest when it has been transformed into a field of dots, so that the viewer/artist can choose how to connect them. Or can choose to leave them as an array of untapped options. The key — both for the drawings and for persisting through the corona context — is in keeping the spirit of play intact, to continue with the path-finding. Generating ever refreshing possibilities for ways to harvest from the fields.