Context and theoretical background

This research is of a curatorial nature in so far as it problematises the activity of mediating classical music and the conditions in which this music is presented. By doing so, it approaches classical and contemporary music production and literature on music performance, history and concert practice from a curatorial perspective. Still largely absent from music discourse, the curatorial approach is interesting in that it combines a wealth of discourses to better understand the relationship between artistic production and presentation. Indeed, multidisciplinary by nature, curatorial discourses integrate elements from different disciplines to discuss and illuminate issues that are common to various art forms. The curatorial perspective I offer here is largely inspired by post-structural thinking and its concern with reflecting on and deconstructing self-evident assumptions, discourses and habits of a practice, along the premise that what seems obvious, or natural, is in fact a construction motivated by many historical, ideological, and/or subjective factors, not seldom concealing or supporting power disbalances and ambiguities. Next to references to philosophers such as Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault, whose attitudes towards historical analyses iinfluenced my reading of the historical evolution of silence practices since the 19th century, I make use of concepts from music philosophy, performance and theatre studies, and theories derived from or inspired by post-structuralism. Thus, authors like Richard Schechner, Marcel Cobussen, Nicholas Cook and Erika Fischer-Lichte are important for this study because their analyses consider the performance situation as an artistic event in its own right. This opens for a much more serious discussion on the different elements which ‘make’ a performance than is the case in studies which see performance only as the representation of an artwork. Anthropology, sociology, and media theory have also been central to the shaping of my reflections. For example, anthropologist Anna Tsing’s take on the assemblage as an open gathering of heterogenous elements not submitted to a common purpose or discourse has been a useful conceptual tool to approach and analyse performance situations. The same can be said for the notion of ‘transitivity’ by media-archaeologist Wolfgang Ernst, consisting of a reflection on the role of communication media in relation to a context rather than purely in function of the message to be transmitted. Additionally, considering the commonalities between different art forms, I have drawn on artistic examples from theatre and the visual arts, and I have used these to critically discuss my own musical creation and experiences as well as recent musical productions by artists such as Ari Benjamin Meyers, Catherine Lamb, Lucia D’Errico, Paul Craenen, MusicExperiment21, and the Ictus Ensemble.

By grounding existing discourses on musical performance practice in a curatorial discourse, this research reflects my background as a performer but also as a curator.1 Curatorship, or curating, is a term commonly used in the visual and performing arts to refer to the activity of mediating artworks and performance. Curators have long remained backstage in the art world, in charge of interpreting and documenting the artefacts of private or public art collections. However, especially after the 1970s, certain shifts occurring in the art scene have progressively added an important public, social and creative dimension to their curatorial role. After the second world war, new roles were sought for art within a society recovering from the social and political upheavals of the previous decades. Artists rebelled against the prevailing tradition of autonomous art, creating new forms of artistic expression no longer fixated on static canvasses, but on performance, unfinished processes and self-reflexive dialogues between people, contexts, ideas and a great variety of media. An example was Marcel Duchamp, whose work illuminated the relationship between the artwork and the context in which it is displayed, demonstrating that it was this context which defines what was or wasn’t considered art. In the wake of Duchamp, context has become a theme in the visual arts and in the arts more broadly, leading to a new paradigm that sees artworks within a context, rather than as autonomous objects. Affected by this development, institutions grew increasingly aware of their social responsibility. Artists started questioning both their own political and ideological motives, and the nature of their relationship with their audiences. Curators became responsible for accommodating emerging art forms within and beyond traditional exhibition spaces, and for mediating between institutions, artists, audiences and society at large. Even though the notion of curatorship is first and foremost associated with institutional curating, it is increasingly considered an artistic practice (Glicenstein 2015). Over time, a feedback loop was established between the two professions, with the work of curators informing the work of artists and vice versa,. This cross-pollination has led us today to speak of artists who work like curators, using strategies inspired by exhibition displays in their own artistic work. We also speak now of artists working as curators, using their artistic experience to curate art shows. Finally, we refer to curators working like and in some cases as artists, using strategies inspired by art to curate events at times considered as artworks.2

Nowadays, the term curating is used very loosely also outside of the arts to designate activities consisting in presenting content in an unusual or particularly thoughtful way. However, I have added to this definition in a text presenting a course I developed on curatorial practices for musicians at the Royal Conservatoire The Hague. What I have suggested is that curating becomes interesting as an artistic practice when it combines, in the activity of mediating music, a reflection on display, context, audiences, discourse and social engagement. Display refers to the spatial and temporal arrangement of media, musical or otherwise. Context points to the occasion, place or the social, historical and political circumstances in which an artwork or performance is presented. The notion of audiences touches upon reception and spectatorship, and it acknowledges the spectators as people with individual concerns, values, agency and needs rather than as an anonymous mass of eyes and ears. Discourse relates, roughly, to the way music is spoken of and the verbal or written material that accompanies musical presentations.3 Lastly, social engagement may involve a concern with topical issues and the needs of a particular community, pedagogical initiatives, and/or gatekeeping. As I understand it, the term implies an awareness for the social, historical and political dynamics of the artistic field, and the way in which artistic work and mediation formats may contribute to reproducing or changing structures of power in society and art. This also includes being mindful of how collective memory, canons, and cultural heritage and traditions are constructed and preserved.

Such considerations have particular bearing for classical musicians, who work with history and music from the past. Crucial questions in this context may include what spaces, traditions and roles to maintain, which to expand or review, whether there are aspects of the past that remain unveiled, and how this music can be relevant today. As art theorist John Berger (1972, n.p.) affirms in a television documentary in which he questions assumptions about European paintings and the way we see them, ‘our way of looking at paintings is less spontaneous than we think’. The same is valid for the way we listen. Art theorist Irit Rogoff (2013, n.p.) confirms that we take a great part of the infrastructures of art for granted without acknowledging the ideological implications that they carry with them:

When we in the West, or in the industrialized, technologized countries, congratulate ourselves on having an infrastructure –functioning institutions, systems of classification and categorization, archives and traditions and professional training for these, funding and educational pathways, excellence criteria, impartial juries, and properly air conditioned auditoria with good acoustics, etc., we forget the degree to which these have become protocols that bind and confine us in their demand to be conserved or in their demand to be resisted.

Part of the curatorial work consists indeed of understanding how certain musical environments such as the classical concert or recordings shape the way we listen, the practice of the musician, and how music is understood. We could call these environments 'sonic apparatuses', in reference to philosopher Michel Foucault's ‘apparatus’ – constellations of practices, discourses, rituals, acoustics, and spatial and temporal arrangements.4 Theoretician Jérôme Glicenstein (2019) explains the extent to which we are used to experiencing art withinin specific apparatuses, which affect the way we perceive an artwork. For instance, recordings or concerts have become so popular over the years that they have ‘domesticated’ our thinking about and/or the performance of classical works. We are so used to the way we hear and experience these works in recordings and concerts, that we have trouble accepting or imagining other ways of experiencing or performing music (ibid, 90).

An example that I will discuss further in Chapter One, concerns developments in the recording industry, specifically hi-fi reproduction technologies. These have made it possible to drastically reduce both background noise and technical imperfections. By doing so, they have enlarged the gulf between music and environmental noise, and affected patterns of expectation for live performances, which are now expected to be as noise-free as recordings. The same applies to the way musicians perform, since the possibility of editing away technical imperfections makes them increasingly mindful of mistakes in live performances. This ideal is so far removed from the acoustic reality and possibilities of live performances that it causes a good deal of frustration for both performers and audiences. Regarding this last point, Robert Philip (2004, 24) writes in his comprehensive analysis of the impact of recording technologies on classical music performance, that ‘[o]nce a musician has had the experience of listening to playbacks and adjusted to them, it is not possible to go back to a state of innocence’.5 Addressing the ways recordings influence performance, composer Michel Chion (1994, 103) points out that this absorption of the real by the mediatised makes us think of live performances in terms of ‘loss and distortions of reality’ instead of as the real thing. Also, the more hi-fi the recording technology, the more capable it is not only of picking up musical tones and the tiniest noises – such as sounds from the electronic circuitry or the performer’s breathing – but also of eradicating those noises. One of the consequences of this eradication is that human presence is increasingly felt less in recordings, and music sounds like it is coming from outer space (see Chapter 1). The intended recorded material becomes overly sharp, and the human factor increasingly absent. The overall result is a musical experience bordering on the ‘uncanny’, to use a term from robotics referring to the emotional response elicited when there is too much resemblance between a robot and a person, causing a strange feeling between suspicion, aversion, and fear about whether humankind can distinguish itself from a machine (Rimini Protokoll 2019). Philosopher Jean Baudrillard (1994 [1992]) criticises vehemently what he considers to be a contemporary obsession with high fidelity. What Baudrillard suggests is that recording technologies, in their search for perfection, have not evolved in the direction of a 'more cogent' musical experience, as once predicted by Glenn Gould (1966, n.p.). Instead, they rather extrapolate the idea of cogency to the point of making music something beyond or even less than real. ‘We are all obsessed with high fidelity’, Baudrillard (1994 [1992], 5) writes, ‘with the quality of musical “reproduction”. At the consoles of our stereos, armed with our tuners, our amplifiers and our speakers, we mix, adjust settings and multiply tracks in pursuit of a flawless sound. Is this still music? Where is the high fidelity threshold beyond which music disappears as such?’ So, while recordings were at first there ideally to capture a sound, now they have become 'teachers', conditioning our musical experience in general. Even within the concert hall, they lower our thresholds of tolerance for noise and mistakes. And if we are to believe Baudrillard, the concern with eradicating unwanted sound has perhaps gone so far that we risk losing sight of music itself.

Interestingly, however, the same recording industry which has made us mindful of noise, is now becoming the agent of an important change in the way we listen. Since the first Walkman appeared in the late 1970s, portable technologies have been making it increasingly common to listen to classical music outside of its traditional venues, through headphones, and in environments that are distinctly noisy. Unlike what one might expect, this new listening habit doesn’t seem to have affected sales of classical music. On the contrary, the growing number of playlists including recordings of classical music in streaming services like Spotify, which is often used on portable devices, indicates that there might be a space for classical music within urban noise (Roberts 2020; Gillam 2022). Also particularly relevant is the way one listens with such portable devices. Even though the availability of noise-cancelling headphones in the last two decades facilitates the acoustic immersion in music, one still relates to the music in a more fragmented mode, since it is interrupted by myriads of unexpected things and situations that we encounter along the way. As a result, we might become less sensitive to the temporal structure of a musical work in its totality, but more attentive to its microstructures or to the sounds themselves. Also, music heard through portable devices belongs nowhere and anywhere at the same time – there is seldom something specific to consolidate its symbolic meaning, as is the case with liturgical music, or with music performed in the legitimising and reverential context of the concert hall. Hence, we start imagining new functions and possibilities for music in general, including classical masterworks. Rather than focusing on whether we listen well or listen musically, there is a wider acceptance for different modes of listening, and researchers have been looking at how these modes have evolved in relation to specific needs and contexts (Liliestam 2013; Dibben 2001; Stockfelt 2006; Herbert 2018).

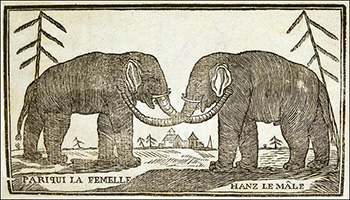

I put stress on the notions of gatekeeping and the sonic apparatus, because they are particularly relevant to my present research and very timely to the extent to which they relate to a much-discussed crisis of attention in contemporary society and its resonances in the classical music field. Supposedly, this crisis is connected to a ‘deficiency of attention’ or a decline in the ability to pay attention – attention understood here as a one-to-one relation from a subject to an object in which the subject ‘detaches’ this object from its context in order to infer something about the object and learn something from this inference. This so-called crisis of attention – critically discussed by, among others, media theorist Yves Citoon (2017), sociologist Tiziana Terranova (2017), and art critic Jonathan Crary (2001) – is often said to be due to certain transformations in the larger social environment that affect the structure of our attention. Before discussing these transformations, it is necessary to consider the historical character of the mode of attention that is supposedly in decline. This historical mode of attention is the way in which attention, as I have shown through the example of the elephants Hanz and Marguerite, is usually conceptualised in the classical concert. Looking back in history, Crary (2001 [1999], 1-2) connects the value attributed to sustained attention to a general focus on productivity in the period around and after the Industrial Revolution, which manifested itself at both a social and individual level as a ‘remaking of human subjectivity’. This ‘remaking’ consisted of the mobilisation of the individual within a rationalised capitalist society in which the disciplining of attention signified increased productivity and control of economic flow. Next to this, it consisted of the involvement of individuals, the bourgeoisie in particular, in a process of self-emancipation affecting both educational and aesthetic spheres, where sustained attentiveness and effort were promoted as a condition for excellence, self-improvement, creativity and psychological emancipation. To ‘produce oneself’ by accumulating knowledge through sustained attention to cultural objects such as music, novels or the visual arts was indeed considered important for maintaining a social position or for climbing the social ladder.

Consistently, new practices and norms of attention developed in schools, factories – as caricatured by Charlie Chaplin in Modern Times – and art institutions as disciplinary tools aimed at sharpening attention to the object or task at hand. In these contexts, the absorbed and conscious engagement with one or a few activities became a desired and trainable skill. Foucault (1977, 35), referring to this period as the ‘age of disciplines’, notes how an ‘art of the human body’ became explicitly mobilised throughout the fabric of an increasingly disciplined society, characterised by strict reforms in education, among other areas. In line with current political and economic interests, this ‘art’ consisted in achieving maximum effectivity from the body (turning the body into an ‘aptitude’) and making it socially productive in a rationalised reality. Considering this within the context of the classical concert, partakers became hyperattentive to the music not only out of interest for the music itself, but also because focus was one of the driving forces of society at the time.6 In a concert situation, sustained attention was facilitated by the implementation of what media theorists today refer to as the principle of the ‘excluded middle’ (Alloa 2020, 148). This supposes that all the media involved in the transmission of a message, the message here being the musical work, should disappear in the act of communication. All sounds extraneous to the work should be either silenced, suppressed or made discreet. The specific structuring of attention in the concert hall corresponds to the appearance of other, similar environments in the urban landscape of the late 18th and 19th centuries, such as museums and public libraries. According to Crary (2001 [1999]), the proliferation of what one could refer to in rough terms as ‘attentive environments’ can be seen as a symptom of how this general concern with attention then affected various aspects of life.

Reflecting on the rationalisation of attention in different domains of life, Crary (ibid, 1-2) points to its consequences for future generations, including my own:

The ways in which we intently listen to, look at, or concentrate on anything have a deeply historical character. Whether it is how we behave in front of the luminous screen of a computer or how we experience a performance in an opera house, how we accomplish certain productive, creative, or pedagogical tasks or how we more passively perform routine activities like driving a car or watching television, we are in a dimension of contemporary experience that requires that we effectively cancel out or exclude from consciousness much of our immediate environment. I am interested in how Western modernity since the nineteenth century has demanded that individuals define and shape themselves in terms of a capacity for “paying attention,” that is, for a disengagement from a broader field of attraction, whether visual or auditory, for the sake of isolating or focusing on a reduced number of stimuli. That our lives are so thoroughly a patchwork of such disconnected states is not a “natural” condition but rather the product of a dense and powerful remaking of human subjectivity in the West over the last 150 years.

Over time, such harnessing of attention has been integrated into the habitus. A concept much used to discuss the interplay between individual behaviour, social practices and the structured environment, habitus was coined by sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. He used it to designate a system of dispositions that determine to a large extent what activities, phenomena and environments we choose to engage with and how we engage with them (Bourdieu 1977, 82-83).7 Habitus is formed in specific social conditions, in and through practical experiences, and in distinct spheres such as the family, school, work, groups of friends and mass culture. Marcel Mauss (1973 [1936]) thought along similar lines when he described bodily techniques as a series of purposeful actions assembled by society for the individual and passed on from generation to generation through education or imitation. Bodily techniques turn our bodies into social instruments and living archives of social memory. It is not easy to get rid of such techniques, for behind even the most commonplace bodily technique such as walking or attentive listening lies a sophisticated assemblage of social, physiological and psychological relations.8 Neuroscientists such as Chris Holdgraf (2016, n.p.) confirm that due to the neural plasticity of the brain, individuals can, with time, learn to effectively orient themselves in a sonic landscape by disengaging certain sounds from a noisy background, especially in relation to ‘targeted sounds’, and in order to infer meaning. This explains psychoacoustic phenomena such as the ‘cocktail party effect’ – roughly, the ability to identify anything speech-like in a noisy environment. A further example is how individuals, in the process of adapting to sound technologies, have developed special listening skills for separating music or speech from noise in technologically-mediated sound, skills which Jonathan Sterne (cf. Bailie 2017, 91) designates as ‘audile techniques’. In sum, not only are individuals supposed to focus, they are trained to do so, even in unfavourable conditions.

Yet, despite this extensive conditioning, Crary (2001 [1999], 1-2), as quoted above, speaks of a growing ‘social crisis of subjective disintegration’ today, characterised by the fact that we pay less and less attention in the ‘sustained’ sense. There is a widespread belief that the development of internet, file sharing, the abundance of information, hypermediatisation, increased ‘screen time’ and other factors make it difficult for individuals today to pay attention in a focused manner. A glance at the plays directed by Frank Castorf at the Berliner Volksbühne during the 1990s and early 2000s illustrates Crary’s point. Castorf was part of the first generation of artists concerned with the plethora of information circulating in the media and in the then burgeoning virtual world. He explored these phenomena by cluttering up the stage with all sorts of objects that obstructed the view, challenging the spectator who would want to see everything by inciting them to ‘work’ to see anything. This proliferation of objects on stage caused confusion and overload in the spectators, who could not assimilate all these impulses or make sense of how they belonged to the overall story of the play. This challenged the kind of attention suggested by the usual mode of engaging with a play (or a musical work), in which the individual is transported to a parallel universe, becoming partly oblivious to the outside world. Instead, the form of hyper-stimulation staged by Castorf and the transitioning between various objects interrupted the mental processes that would allow the spectator to synthesise their experience. Theatre theorist Hans-Thies Lehmann (2006, 89), referring more generally to the lack of apparent causality in plays such as Castorf’s, speaks of a ‘helpless focusing of perception’, and a ‘search for traces’, preceding a process of meaning-making that is perpetually postponed: one wants to understand, but there is always a new element emerging that prevents one from doing so.

While socialisation agents (e.g. schools, family, religion and workplace) in the late 18th and 19th century were relatively homogeneous, operating under similar principles and forms of discipline, today the field of socialisation is hybrid and diverse. Different instances of socialisation coexist, with multiple contrasting projects and a greater circularity of values and identity references and configurations. Media particularly produce models and dispositions that are sometimes very different from what one learns at home or at school. The influence of these distinct socialisation agents gives rise to new experiences, cultural values and identitarian references, and makes our habitus broader and more flexible. According to sociologist Maria da Graça Jacinto Setton (2002), this makes the 21st-century habitus a flexible system, ‘adaptable to the stimuli of the modern world’. Especially true of today's diversity of references, is how the habitus becomes less sedimented; we have become more interested in different things, but it is more difficult or less interesting to engage with practices that consolidate over time through much repetition. Along the same lines, sociologist Cas Wouters (1998) identifies a transformation of our basic personality into something more malleable, craving diversity, less formal or interested in hegemonic and disciplining practices. Such changes in the individual’s capacity of paying attention has repercussions in various fields. As educator Maryanne Wolf (2018, n.p.) notices, the confrontation with massive amounts of information and stimuli makes us lose what she calls ‘cognitive patience’, so that the ability to immerse ourselves in something is now a thing of the past. As she explains:

Perhaps you have already noticed how the quality of your attention has changed the more you read on screens and digital devices. Perhaps you have felt a pang of something subtle that is missing when you seek to immerse yourself in a once-favorite book. Like a phantom limb, you remember who you were as a reader but cannot summon that ‘attentive ghost’ with the joy you once felt in being transported somewhere outside the self. It is more difficult still with children, whose attention is continuously distracted and flooded by stimuli that will never be consolidated in their reservoirs of knowledge. This means that the very basis of their capacity to draw analogies and inferences when they read will be less and less developed. Young reading brains are evolving without a ripple of concern from most people, even though more and more of our youths are not reading other than what is required, and often not even that: “tl; dr” (too long; didn’t read).

Introduction

GROUND: Preparatory coating or a foundation layer on a support that renders it more suitable for the application of paint or other artists’ media.

(The Grove Encyclopedia of Materials and Techniques in Art)

In May 1798, scientists and music professors gathered at the Jardin des Plantes in Paris for an orchestra and choir concert featuring two unusual guests: Hanz and Marguerite, an elephant couple from India, newly arrived in the French capital. The concert was a scientific experiment whose purpose was to ascertain whether creatures that had never been exposed to music would react to it in the same way as humans did. Reporting on the experiment, the journal Décade Philosophique (cf. Johnson 1995, 130) describes the behaviour of the elephants as follows:

Hardly had the first chords been heard when Hanz and Marguerite stopped eating; soon they ran to the site from where the sounds emanated. This trap door open above their heads, these instruments of strange forms whose extremities they could scarcely make out, these men who seemed suspended in air, the invisible harmony they tried to touch with their trunks, the silence of the spectators, the immobility of their cornac – everything at first seemed for them a subject of curiosity, surprise, and apprehension. [...] But these initial movements of apprehension gradually diminished as they saw that everything around them remained calm. Then, yielding to the sensations of the music without the slightest hint of fear, they at last shut out all sounds apart from the music.

It would seem that, while Hanz and Marguerite were first disquieted by the music, the calmness of the environment appeased them and they soon became absorbed in the music, ignoring the world around them. From a scientific viewpoint, the soundness of this interpretation is questionable, since one cannot in fact know how the elephants interpreted the situation. To be able to say with any degree of certainty that the elephants were calmed by the sounds of the music it would be necessary to conduct many similar experiments. The claim that the elephants had to ‘shut out all sounds’ that did not belong to the music is purely fanciful and impossible to prove, especially given the scientific means available at that time. Rather than what was going on in the brains of elephants, the conclusion drawn from the experiment is suggestive of what was going on in the brains of the scientists and musical authorities in charge of the experiment. In other words, while the experiment may lack scientific consistency, the way it was interpreted reflects certain expectations towards the music and its ability to spellbind the listener. More broadly, it reflects the belief that the more one can abstract oneself from everything but the object being focused on, the more clearly one is able to perceive this object.

The context in which this experiment was realised, helps explain why this way of thinking about listening imposed itself over the centuries, persisting to this day as an ideal mode of engaging with classical music. The musicians and music professors that participated in the experiment belonged to the Paris Conservatoire, which had opened its doors three years earlier. The first of its kind in Europe, the Conservatoire established precepts for musical education and for the conservation of classical music heritage that are still followed today in institutions worldwide. It was also the period in which public concerts started gaining in popularity in European and North American capitals. Although many forms of concerts had coexisted since the 18th century and continue to do so today, a generic format emerged which I call here the ‘classical concert’. The classical concert is based on the notion of autonomous listening, that is a form of listening focused only on the music. Music, in this context, became the source of an artistic experience based on a significant encounter between an individual listener and a musical work. Along with the notion of autonomous listening, the idea that musical works require a background of silence in order to be performed and heard adequately became widespread. This idea manifested itself practically in the way that concerts, and also the recording industry, exclude or make discrete everything that might divert attention away from the music. Against a background of silence, the music seems more immediately accessible, and is also preserved from interruptions that disrupt its temporal coherence. In short, in such protected conditions it feels like musical works appear to the listener, within certain limits, in their ‘original state’, that is, as the acoustic realisation of musical ideas once produced in and by a composer’s mind.

Combining my professional experience as a curator and as a performer of classical and contemporary music, the goal of this dissertation is to highlight the connections between attention and silence, to investigate how silence contributes to the performance of classical music, and then to propose an alternative mode of performance based on what I call metaxical amplification. The concept of metaxical amplification, in which the performance of classical works coexists with other sounds, is inspired by the Ancient Greek notion of metaxy, that which is in-between. Aristotle used the term to indicate the mediating field between the perceived object and the perceiving sense, such as for instance air, or skin. In my performances, the metaxy refers to the environment of performance. It specifically refers to sound-producing elements, such as the action of the instrument, the creaking of floors, the breathing of the performer, or the steps of the audience, which are amplified by electronic means. During my research, I have tested metaxical amplification in two performances. touchez des yeux was realised at the De Bijloke Muziekcentrum in Ghent in 2018. Interferences was presented at the Escola Superior de Música e Artes in Porto in 2019. These two performances lay the ground for a reflection on how the inclusion of environmental sounds in the performance of classical works in a concert hall affects attention, and how this modifies the practice of the performer and their relationship with musical works.

The difficulty of processing large amounts of information as well as the loss of cognitive capacities as described by Wolff, such as the ability to perform deeper comprehension and reflection tasks, together produce a subject whose capacity for paying attention is inferior to the wealth of information that consumes this attention. In terms of the market, the new media and technological affordances that Wolff refers to have been heavily exploited for financial profit. Terranova (2012, 7) warns against the mechanisms of this ‘economy of attention’, where attention is being managed as a currency and as a valuable but scarce resource. What is at stake is how to orient the attention of the users, how to make them focus, and how to make them consume or pay attention to this rather than that.

In the field of classical music, but also of contemporary music, practitioners are faced with a dilemma. On the one hand, there is the practice of performance and mediation that is constructed to a great extent upon the principle of sustained attention to and absorption in the musical work. On the other hand, there is a contemporary reality in which, as it seems, it has become increasingly difficult to concentrate. What are the consequences of these developments for the reception and practice of classical music? An object of much debate is how the way classical music is traditionally heard, in concerts or in the privacy of the home through hi-fi systems, seems to be at odds with today’s lifestyle (Abbing 2006; Rebstock 2011; Burland and Pitts 2014; Brown and Novak-Leonard 2011; Gembris 2011; Idema 2012). In these discussions, sociologist Martin Tröndle stands out as one of the most present voices. For Tröndle (2011, 27), the defining element for the success of the classical concert in the last two hundred years has been its ability to mobilise the attention of the audience towards the musical event. Instances of this mobilisation of attention include creating a sensation of acoustic and physical intimacy, centralising the ear of the listener on the performer, or through the crystallisation of a particular expectational structure based on familiar rituals and repertoire. This format does not do well in a society where inattention and lack of formality seem to have become the habitual mode, leading Tröndle (ibid, 14) to speak of a ‘crisis of the classical concert’. The behavioural conventions associated with high art would seem to be particularly dissuasive: young people today are used to a different type of socialisation with live music; for them, the formal rituals of the classical concert are both unfamiliar and rebarbative. It has also been argued that individuals become increasingly used to ‘multilistening’ (as in multitasking) and to the multiple perspectives arising from listening to music through portable technologies, in different environments or inserted in curated playlists. These are all forms of engagement with media that make us more receptive to a diversity of content, but simultaneously more resistant to one-dimensional modes of transmission (Herbert 2018; Elsaesser 2017). Cultural historian and musicologist Ola Stockfelt (2006, 89-90) confirms how media have made us accustomed to hearing music in the most varied and acoustically messy environments, but also in different positions, and while doing all sorts of things: walking, showering, driving, being in the cinema or in the bathtub, climbing mountains, and so on, making the idea of an ideal listening space and mode more abstract.

In this context, absorbed and synthetic listening aimed at the auditory reconstruction of a work have become less interesting than more serendipitous forms that do not follow one direction. Without ‘proper’ attention to the music, however, it is claimed that there can also be no structural engagement with the composition being performed, which might compromise the comprehension of its complexities. Yet, as I describe in Chapter One, the classical music industry is constructed upon this very form of appreciation and understanding of the musical work. As philosopher Lydia Goehr (1992, 18) rightly remarks, since the 19th century it has all revolved around an understanding of the work, understood as an abstract and ideal identity which the performance realises in sound: ‘There were concerts of works, reviews of works, scores of works, musicological and aesthetic theory based on works and so on’. Goehr (ibid, 2) has expanded upon how musical works have progressively acquired metaphysical importance as ‘original and unique products of a special creative activity’, objects that allow listeners to develop their ever-expanding sensibility. Music became the works that we listen to, that we play in concerts, that we talk about, that we surrender to. Musical works became ‘things’ we have come to know and cultivate, that we respect as if they are living beings (Abbate 2004, 517). Thus, listening became a moral obligation towards the work. Musicologist Lars Liliestam (2013) and music psychologist Ruth Herbert (2018) have done relevant work in categorising different modes of listening. What they found is that music-theoretical discourse is still profoundly marked by what Herbert calls an 'insidious influence of autonomy'. Despite an increasing awareness for the new ways of listening as mentioned above, there remained the persistent idea that listening should be oriented towards a structural understanding of the musical work only, without regard for a larger context or the situatedness of the performance and/or the listening event. Liliestam notes, not without bitterness, that modes of listening other than those dedicated to the comprehension of the work, are often described in the literature as inferior, irresponsible or superficial. The ‘right’ way of listening to classical music is the focused, concentrated and absorbed mode. Any deviation from this mode, any distraction, would mean that we are not actually listening to the music: '[C]oncentrated listening is implicitly seen as an ideal, […] listening is of a poorer quality if you do something else at the same time as you listen to music’ (ibid, 5).With attention being so important for some musicians and scholars that it provokes this type of judgement, it is no surprise to see debates on attention occupying the field.

Nevertheless, as with all transformations, responses from the field diverge. Some insist musicians insist on focus. Just recently, I saw pianist and composer Frederic Rzewski refusing to start a performance because of the noise the air-conditioning system was making. Others conceive performances that place extra focus on deep attention. This was the case in Marina Abramović’s performance A Different Way of Hearing, where spectators were first supposed to attend a preparatory workshop. This included meditation and long moments of silence meant to 'rinse the ears' from everyday sounds before they attended the concert. This took place in the company of a personal supervisor, who ensured that attendees handed in their electronic devices at the reception and remained silent during the entire seven-hour concert. Abramović conceived this project in reaction to the superficial and scripted way live classical music is listened to today, a mode of listening enhanced, or provoked by our hectic lifestyle (‘the tempo of life, thoughts, stress or smartphones’). In the announcement of the project, Abramović (2019) writes, ‘[How] can listening to music take place as an authentic, moving, profound, and transcendental experience? […] In the midst of our busy lives, can we transform how we experience music?’

Yet another strategy is to capture the attention of concertgoers by attracting them to the music indirectly, through a more intense experience of that which surrounds the music. Theatre director and curator Matthias Rebstock (2011), for example, proposes different solutions: ‘auratising’ the performer, for instance by cultivating stardom (ibid, 144); using visualisation techniques to enhance focus on the auditive through sight (ibid, 148); using technology to enhance proximity to the performer or to boost particular basses and other elements likely to have a direct impact on the listener’s body (ibid, 147); or staging the listening experience by presenting concerts at unusual hours and places, using special scenography and listening in unusual positions. He gives the example of concerts in swimming pools or planetariums, or the late-night concerts at the Berliner Radialsystem where the audience can lie down to listen instead of sitting still (ibid).9 When conceiving these strategies, Rebstock was much inspired by the writing of literary theorist Hans-Ulrich Gumbrecht, who in Production of Presence (2004) expressed concern for our obsession with content and the interpretation of this content – a message, a book or an artwork. This concern can make us forget the physical affection that the world can have on us. Rebstock wants to revive the conditions for such affection. The strategies he proposes aim to ‘produce presence’ (ibid, 146), meaning they make the listener feel physically implicated and maximise their attention not only toward the music but also toward the event as a whole. Rebstock’s ideas are not without interest for my own work in the sense that they explore physical situatedness and the material impact of the performance environment. However, although various aspects of performance become more prominent in the examples that he gives, they continue to function as a support for the musical works.

While artists like Rebstock or Abramović seek to recover and intensify attention to the music, others explore distraction and what I will for now call ‘inattention’ as a creative resource. Indeed, since the desperation or perplexity of the Castorf generation, we have become more used to a downpour of media and to a hyperventilating reality. Many artists embrace this new reality, in which it becomes increasingly difficult to pay attention in a traditional sense. This is not because they necessarily enjoy or approve of these transformations, but because, when faced with a situation that seems irreversible, it seems to them, as it does to me, that it is more productive to try to understand and deal with new modes of attention than it is to resist them by sticking to the old. Take distraction, for instance. Defined in the Online Etymology Dictionary (Harper, n.d.) as ‘the drawing away of the mind from one point or course to another or others’, distraction is commonly and negatively considered to be the ‘reverse’ of attention. It precludes real contact or relationships with someone or something, as well as the effort necessary to synthesise complex data and sequences of events into a coherent whole. Therefore, distraction is often associated with superficiality and a kind of defeat – the subject gives in to the many forces that claim their attention, unable to recentre themselves (hence the ‘subjective disintegration’ of which Crary speaks).10 Seen differently, however, one could also think about distraction as a form of resistance. As Citton (2018, n.p.) suggests, resistance can be seen as a contemporary way of ‘renouncing the authority of the imposed message’. Here, the imposed message is the undisputed way in which sustained attention is commonly considered as something important and good, but also the hegemony of the message itself, whose coherence is taken for granted and never questioned. Besides, at a perceptual level, although distraction eludes synthesis, it may facilitate the making of connections, since the distracted individual will engage with objects or events that someone absorbed in the contemplation of one object would not be able to hear or see. Returning to Castorf, this impossibility of focusing, counter to the ‘habitual mode’, can activate the imagination in unexpected ways. So Lehmann (2006, 84) notes about the mental activity of the spectator in front of multiple stimuli and chaotic stages:

The human sensory apparatus does not easily tolerate disconnectedness. When deprived of connections, it seeks out its own, becomes “active”, its imagination going “wild” – and what then “occurs to it” are similarities, correlations and correspondences, however far-fetched these may be. The search for traces of connection is accompanied by a helpless focusing of perception on the things offered (maybe they will at some moment reveal their secret).

What also seems to be gained, in addition to new connections and despite the helplessness of the individual as the mind transitions rapidly from one sign to the next, is a form of intensity and presence. Lehmann (ibid, 83) speaks of ‘the density of intensive moments’ – the sensation, so rarely felt, of being in the now, arising from the fact that each interruption to the individual’s efforts to focus on one or the other sign, brings them back to the here and now where perception occurs. What distraction and inattention suggest, then, is that we find ourselves in an environment that is multi-layered, with many impulses to relate to; rather than being only disorientating, this can also be potentially rich and stimulating. Owing to how distraction can stimulate relation-making and physical situatedness, artists increasingly see distraction or variations thereof as legitimate and possibly productive modes of engaging with sound. This manifests itself in many artistic proposals to which I will return in Chapter Four, which are being conceived around notions of connectivity and presence rather than synthesis and structural understanding. These include the Rasch series by the artistic research programme MusicExperiment 21 (ME21). Under the pretext of expanding the notion of the musical work, they included in their multimedia performances a variety of materials associated with a musical composition; the Kunsthalle for Music by Ari Benjamin Meyers, in which several works are performed as if in an art exhibition, simultaneously and in different corners of an art gallery; and the Liquid Rooms by Ensemble Ictus, which are informal performances of contemporary works on multiple stages during which the listener can go in and out of the concert hall as they please.

In my own work, concern with attention has from the start been connected with the problematisation of aspects of musical tradition. It is specifically concerned with the habit of performing musical works in closed environments free of noisy sounds – here defined as sounds considered extraneous to the composition being performed and thus potentially distracting, sounds typically unwanted in the concert hall. This concern arose from certain experiences and incidents that have made me reconsider noise as an opportunity, rather than as a disturbance to the attention of performer and listener. I am thinking particularly of a concert with soprano Ingeborg Dalheim in which we performed a duo for piano and voice by Helmut Lachenmann, Got Lost. In the middle of the piece, our performance was interrupted by the sounds of an electric guitar pouring in louder and louder onto our stage. Got Lost is a long and complex piece, and the passage we were playing at the time of the incident was particularly quiet. From the stage, we could feel the tension in the hall. In an unexplainable reflex, communicating almost if by telepathy, Ingeborg and I did not stop playing. Instead, we slowed down emphatically, listening intently as the distortion of the guitar filled our silences. Our performance became more plastic and reactive as we began playing ‘in the moment’, attentive to both the composition and these emergent sounds, and improvising with these sounds. There and then I savoured the interference, yet my rehearsed pianistic gestures appeared theatrical and overstated in this new situation, making me consider the distance between our carefully planned interpretation and the spontaneity of the guitar sounds as they entered the space. Sounds like these, emerging unexpectedly during the performance of classical music, are generally considered noise: disturbing, unwanted and uncontrollable, out of place in the universe of the musical work. Here, however, they brought freshness to our performance and a new freedom in relation to the music as notated in the musical score.

This made me reflect on my experience improvising with noise musicians or performing contemporary repertoire in which these same sounds are used as musical material, often in order to propose new perceptual experiences and/or as a means of opening the closed universe of the concert hall. An example is prisma interius by Catherine Lamb, which uses street sounds picked up by microphones and played back inside the performance venue. Although I can control the volume of the playback and turn the speakers on and off as I perform this piece, I have no control of how these sounds will sound. I have no control of their sonic properties, nor can I predict how they will unfold. For me as a classically trained performer, who is both used to mastering my instrument and being able to imagine how the tones I play will sound, this lack of control is challenging. It is, however, also an opportunity to be more present and more open to the physical now of the performance. In this present mode I pay attention to both the musical work and the larger sonic environment I am in, rather than constantly evaluating what I play in relation to what I would have liked to play and to the tones and rhythms specified by the score.

When conceiving my metaxically amplified performances, I had such experiences in mind. I was looking to expand both my field of attention and the ‘margins of indeterminacy’ of my performance, through the surprise element introduced by sounds that I could not control. I was curious to see how this expansion would affect my approach to the work, which was sometimes too rigidly determined by the score, the codified situation, and by expectations I had towards my playing. Such expectations formed through years of engaging with performing conventions, and I often had trouble finding my own voice. I worry about this rigidity because as a performer, but also as a contemporary music curator, I have felt the limitations imposed by the models within which I was educated and in which my professional life unfolds. As an interpreter, I feel connected to and accountable for this legacy. As a musician and curator, I feel the need for dialogue with a broader contemporary context. But, in fact, these two perspectives and needs do not often overlap. I wondered what would happen with the two ‘rocks’ of my practice, the musical work and its attached performance traditions, when entering into dialogue with the noise of the environment instead of being protected by silence. In a sense, I was imagining a transgressive practice with its traditions corroded or transformed from within, as happens during marine transgressions, when the water of the sea rising naturally deforms the sediments on the seashores.11

For these reasons, I call the performances developed during this research ‘grounded’, in reference to a text by Gilles Deleuze in which he describes the innovative painting technique of Caravaggio, who instead of painting upon a ground, used the paint contained in the ground to create his images. The idea of painting with the ground, although it clashes semantically with the marine metaphor, is actually close to it in the sense that it describes a form of affection between the elements of an ecosystem. As I will explain more thoroughly in Chapter Two, Caravaggio’s technique seemed therefore to build a pertinent parallel with my intention of transforming my practice from within, performing with the sound of the environment rather than against it. In this study, these grounded performances become experimental situations where I explore how metaxical amplification, by reclaiming the noise and fluctuations of the performance environment instead of filtering them out, does the following: it destabilises the traditional centrality of the work and its representation; it challenges the autonomy and aesthetic self-sufficiency of the work; it proposes new functions for this work; and it changes the performer, who improvises and listens in and with the present as it entangles with musical interpretation.

To conclude this introduction on a practical note, I divide this thesis into four parts. Chapter One considers the importance of a silent background for the performance of classical music from a historical and practical perspective. Based on musicological research, I look at how social codes and the cultural imaginary of the 19th century, as well as acoustic and technological developments, have contributed over time to the eradication of noise in the classical concert and on recordings. I also examine my own practice as a classical performer and testimonies by pianists and music teachers to understand why a silent background might be necessary for the construction of a musical interpretation.

Chapter Two deals with the performative potential – within the context of classical and contemporary composition – of environmental sounds traditionally considered as noise, that is as unwanted or disturbing sounds. I explain how my experience with these ‘noisy’ compositions inspired me to develop the notion of metaxical amplification. In the second part of the chapter, I describe the implementation of metaxical amplification in what I subsequently came to call grounded performances, discussing their motivation, outcomes and inconsistencies. A special highlight is given to the evolution from the first performance, touchez des yeux, to Interferences, presented a full year later.

Chapter Three continues with a reflection on my grounded performances. I focus on the way the juxtaposition of heterogenous sounds – environmental sounds and the acoustic realisation of the musical work – challenges attention, and with this also the mode of performance and listening discussed in Chapter One. Here, constructed interpretations, structural hearing and absorption, which I had previously presented as the foundations of my pianistic practice, are replaced by practices of improvisation, multiphonic listening and modulating forms of attention.

Finally, in Chapter Four, I discuss my personal attachment to tradition and to classical works as well as possible visions for the future of my practice. I explain first how my artistic work in this research started out quite conventionally, from the interpretation of musical works, and how this conventional practice evolved into an intervention in the environment of performance. Comparing my practice with the work of other musicians, but also with the use of text in theatrical stagings, I reflect upon how unconventional approaches to performance traditions may result in new ways of treating the musical score and of understanding the musical work. The realisation of the musical work is no longer considered the centre and purpose of the performance, but rather a pretext for more inclusive experiences. I conclude with a biographical note explaining the personal necessity of this study in my artistic trajectory, its limitations, and the new perspectives on my musical practice gained through this artistic research.

Methodologically speaking, the research and the account presented here evolve as a tight but achronological feedback loop between theoretical and artistic material, and my own artistic experiences and work. The research started with loose theoretical references and rough ideas about possible performance concepts and a desire to explore new relationships with musical works from the past. In 2018, these initial premises led to the creation of a first ‘grounded performance’, touchez des yeux. As I will explain in Chapter Two, rather than directly addressing the insights discussed in this dissertation, touchez featured ideas and choices pointing in several and often contradictory directions.The second grounded performance, Interferences, on the other hand, was conceived one year later as the result of a thorough reflection triggered by the analysis of touchez. This work first brought into focus the question of attention, motivating me to look back at past experiences as a performer and engage historically and theoretically with the significance of silence and sustained attention for the performance and reception of classical music as described in Chapter One. This in turn led to the crystallisation of the notion of metaxical amplification, and to insights about the consequences of such amplification for the understanding and function of the musical work. These insights induced a thorough engagement with the literature studied in the beginning of the research as well as with new references, spanning across several disciplines including cultural and media theory, sociology, theatre, the visual arts, musicology and philosophy. The engagement with literature served primarily to strengthen my findings and insights, whereas examples from recent musical performances and artworks from other fields were approached critically, either to draw comparisons with my own work or to offer new perspectives to the theoretical material.

This intricate process is mirrored in the documentation presented in this thesis. Even though it includes recordings of some of my earlier performances and works of other artists, the documentation of my grounded performances is scarce in the case of touchez, where it based mostly on photographs, and even inexistent in the case of Interferences. This was a conscious choice. In photographing the performance of touchez, Maarten de Vrieze didn’t seek to give a global picture of the situation. Instead, he chose to register what I would call ‘footnote moments’, elements such as cabling on the ground, heteroclite objects, the handrail of the stairs, a wrinkling of lips and ears almost imperceptible to the eye. Unaware of the scope of my research, he accidentally (or, more likely, influenced by what he heard) contributed to its making by providing me with documentation that reflected what I had set out to study, without me having already consciously identified what this was: the performance environment and its usually ignored details. In other words, studying the photographic documentation of the performance was as essential for the development of my research after touchez than the experience of the performance. I include it in the dissertation in order for the reader to follow this process and to better understand my subsequent choices and direction. A sound documentation, on the other hand, would hardly have been enlightening, since it was difficult, if not impossible, to properly document a performance as experiencing it was highly situational, depending on being in that space, and on walking from speaker to speaker in one’s own pace.

When it comes to Interferences, the motivation not to include documentation was slightly different. The setting was straightforward, with the pianist on stage and the audience listening from the auditorium in a darkened room. There would not much to be seen in photographs that would differ from a conventional concert experience. Regarding sound, however, the situation would not have been so difficult to document. Showing the documentation here, however, would mean inviting the listener to look for correspondences between the documented material and the theoretical insights of this dissertation, to the detriment of the experience of the situation itself, which is at the very core of this study. It seemed more interesting to me then, to craft my written descriptions of the performance in such a way as to stimulate the listening imagination of the reader, rather than presenting documented material as evidence or proof. In a similar effort to awake the sonic imagination of the reader, I present in Chapter Two a sound collage made of fragments of recorded material from touchez attached to a slide show of the photographic documentation of the performance. Thus each photo has its own length and sound. The function of this collage is not to have the reader imagine how the performance could have been, but to propose a third artistic output to the thesis by translating the multiphonic situation described in Chapter Three to the reader, whose attention will hopefully be challenged by the coexistence of sounds and written words. This in order to prepare the reader for the theoretical reflection proposed in Chapter Four.

Finally, the insistence on photographic documentation also has its origins in my extensive collaboration with photographer Karen Stuke on touchez, described in detail in Chapter Two. Stuke works with pinhole photography, a technique that allows the photographer to capture multiple temporal layers in the same image. As is characteristic of pinhole photography, the longer the opening time of the shutter, the more light enters the camera, causing all that moves in a given situation to become fuzzy. For instance, in Stuke’s photos of me performing Schubert, I can be seen vanishing behind the piano and the score. Observing these photos has made me extremely sensitive to the physical environment of the performance, and to look at it from different perspectives. It was in many ways the beginning of the research as it is presented here, for it raised questions. If the pianist vanishes in a situation in which she is so incontestably present, the picture seems to ask: What are we actually seeing and listening to? What goes on when I perform?

Ensemble neoN performs at the Borealis Festival 2022 with noise/improvising musicians from the Far East Network – FEN (Otomo Yoshihide, Ryu Hankil, Yan Jun and Yuen Chee Wai)and Lasse Marhaug. Read more about this performance in the concluding chapter.