The way text has come to be dealt with in theatre was one of the first inspirations for my own research. My interest in theatre was sparked by a year spent as a participant-observer of the bachelor course in theatre direction at the Oslo National Academy of the Arts between 2010 and 2011. One of the exercises of the course consisted in creating ‘opening structures’, or non-narrative situations that introduce a play by establishing a context and an atmosphere for the subsequent action.1

These opening structures included a variety of media such as light, movement, image, sound and so on. I recall for instance spreading scents into the air, and making spectators walk through tunnels and on wet ground. Defining their success involved the combination of psychological discernment and a great precision in the use of different media. Through these thought-provoking exercises I have learned that theatrical elements have their own form of presence, and that they can be calibrated or ‘voiced’ to create different meanings independent of a text. A few years later, hosting theatre theorist Hans-Thies Lehmann and theatre directors Heiner Goebbels and Tore Vagn Lid at the Ultima Academy, I became better acquainted with the way postdramatic practitioners experiment widely with the boundaries of traditional theatre by creating interactions between classical texts and contemporary discourses, or by including audiences and reality (the ‘outside world’) as co-players on stage (Lehmann 2006). This approach to text was rather stimulating compared to the strict Werktreue tradition in which I was trained.2 Together with the experience of opening structures, the theatrical freedom in the use of texts informed the conception of grounded performances, since I could now think of texts, including musical texts, as yet another ‘voiceable’ element in a performance, and not necessarily the central one.

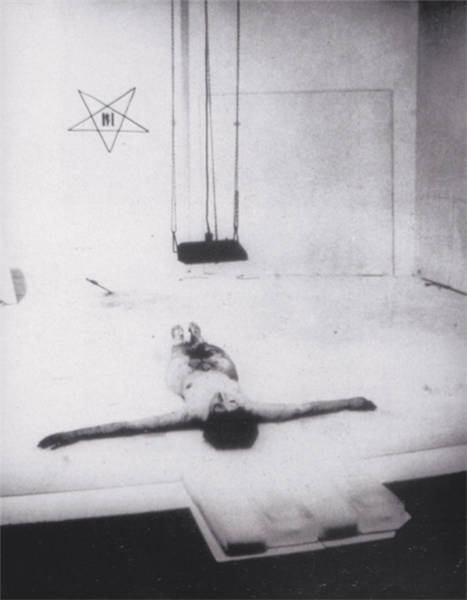

Many scholars and musicians in the field of classical music have located the authority of tradition in the preposition ‘of’. Classical performers do not just perform. They perform something, this something being music, or a musical work. The ‘of’, in these cases, refers to the representational nature of musical performance, that fact that it represents or mediates a work. This is different from the term performance as used in the visual arts. Performance in the visual arts, as practiced since the Dadas and Futurists and especially after the 1970s, is not followed by the preposition ‘of’, since the main characteristic of performance art is its refusal of the art object and the very principle of representation. Artists perform because they realise actions that are performative in the sense of Austin and Butler (see Chapter Two), particularly actions that are not fictive and meant to have a transformative and often controversial impact on a given social, artistic or political context. As art theorist Jonah Westerman (2016, n.p.) remarks, ‘performance is not (and never was) a medium, not something that an artwork can be but rather a set of questions and concerns about how art relates to people and the wider social world’. This was demonstrated by Marina Abramović in the 1975 performance Lips of Thomas, in which she was not performing an artwork or a play, but rather testing the impassivity of the spectators as she flagellated herself in front of them for hours in a row (Fischer-Lichte 2008). In classical music, however, the object of performance is precise. One speaks of the performance of music or of a musical work. In what follows, I will look at different interpretations and subversions of this ‘of’, both theoretically as well as through examples of performances that I attended during this research, which shed light on some of the concerns addressed by my grounded performances.

Performers have a responsibility towards the work and the composer, shaping their performances according to the Werktreue principle, or ‘fidelity to the work’. This principle, as cellist Tanja Orning (2014, 296) claims, has ‘an almost incredibly strong hold over performance’, affecting not only instrumental performance but also musical discourse, perception and mediation formats, as I too have shown in previous chapters. By contrast, PMP is concerned with the ‘doing’ of the musician and/or the impact of the performance on the spectator regardless of whether the performer is strictly obedient to the score. ‘Even if the sonorous event remains central, the perfect musical performance […] regards that event as inseparable from the actual performers who produce the sounds, from the formal, visual choreography of their musical movements, and from the real spaces or environments, acoustic and cultural, which shape it’ (Goehr 1996, 18). In other words, in contrast to the ideal universe of the musical work, PMP is about energy, the body and gestures of the performer, the delight of the audience and the social experience. Goehr’s distinction between PMP and PPM is of course schematic. In fact, as she explains herself, most of the time mainstream performance practice consists of a combination of both, with performers finding themselves very often in a ‘strained’ condition (ibid, 12) where they try to reconcile their belief in free and subjective interpretations with their desire to comply with the original ideas and intentions of the composer as specified by the musical score.

Artist researcher and guitarist Lucia D’Errico (2018a) deals with this paradox imaginatively, using the ‘of’ as a space in which to 'resist' or reconfigure her approach to the score and the work. More specifically, for D’Errico the ‘of’ represents a tension between faithful representation and the possibility of transformation contained in the act of translating the notated sign. It is like the canvasses of Francis Bacon, where the skeleton or sketches of the depicted images are visible behind the image, attesting to the temporal evolution of the painting and the many transformations that occurred between these first outlines and the final product: ‘The canvas of the of, devoid of actual materiality and at the same time burdened with the virtual inertia of the past is the place of a crucial transformation' (ibid, 13). The way this materialises in her practice is by refusing conventional correspondences between the musical symbols in the score or the sounds she hears in a recording, and their acoustic realisation in performance. The decoding of scores and recordings happens via their association with former sonic experiences which she uses as a starting point for improvisation and new creations that may well include media other than sound. In brief, rather than rejecting the traditional ‘image-of-work’ and the materials generally used to construct it, she subverts this image, using it to explore the musical past and the way the latter manifests itself when she listens to music or reads scores. From the perspective of my own work, I see in D’Errico’s explorations a parallel to the idea of metaxical amplification, since the musical work becomes for her a site of figurative amplification of her personal relationship to music, and as such, the pretext of an exploration that exceeds the work itself. Also, I find relevant the way in which D’Errico insists on calling her own creations ‘performances of musical works’ rather than compositions. This distinction might seem superfluous at first, but for the performer its consequences are immense. While composers, throughout music history, have transcribed and arranged scores by other composers, and have imprinted their own views upon somebody else’s music, performers are not used to ‘touching’ these scores. Tinkering with or modifying them, as I have done in my performances, is in many senses a subversive act.

As Szendy suggests, Adorno’s views on listening are polarised: he denounces any form of listening other than those aiming at the understanding of the structure and content of musical works. He (1976 [1962]) writes that the analysis of listening must be done from the thing itself, i.e., from the structure of the music which provides objective data against which to measure the adequacy of listening. Although Szendy’s critique on Adorno is understandable, so is Adorno’s attitude, when considered contextually: For Adorno, listening to music was a serious, politically emancipating and self-cultivating activity. Therefore, there might have been a concern that non-focused forms of listening would banalise this important relationship to music or ignore the music’s important socio-critical function. Such concerns were shaped, for instance, by the listening ‘revolution’ brought along after the 1950s by the rise of the recording industry and the increasing popularity of ambient or ‘wallpaper’ music in offices and public spaces. These cultural, social and political trends were perceived as harmful by Adorno and many of his kindred spirits. Consuming music without proper attention meant falling prey to the forces of thecultural industry, producing lazy listeners and alienated subjects. It turned music into a commodity, into something that was used rather than disinterestedly appreciated. The fear, then, was that the neoliberal logic of consumerism and lack of criticality reflected in these trends would affect the relationship with art, and therewith art’s emancipatory potential.

And yet, such views on listening, as already alluded to in my Introduction, seem nowadays to be falling out of fashion. Adorno himself, in his later texts, already adopted a more open attitude to listening, considering that certain works or situations might invite to or even require different listening strategies. As curator Monika Pasiecznik (2012, n.p.) writes, non-judgementally, about Liquid Rooms, they are ‘[an] invitation to another kind of listening, more diversified, fragmentary, of differing intensity, full of associations and free drifting of thoughts’.Indeed, one recognises in the freedom given to the listeners to Liquid Rooms – the explicit possibility of entering and leaving the performance space at will – both the wish to connect to a contemporary culture characterised by growing informality and to an ecological listening. Listening ecologically is theorised by Herbert (see Chapter Three) as a combination of distraction and intensity, where the listener also focuses on things other than the music’s structural unfolding. This worked for my non-musician friend, who, albeit more used to contemporary concerts, experienced this one as a space of freedom, because the possibility of deciding for herself when, what and how to listen made her feel more willing and less pressured to engage with the music.

Why Schubert

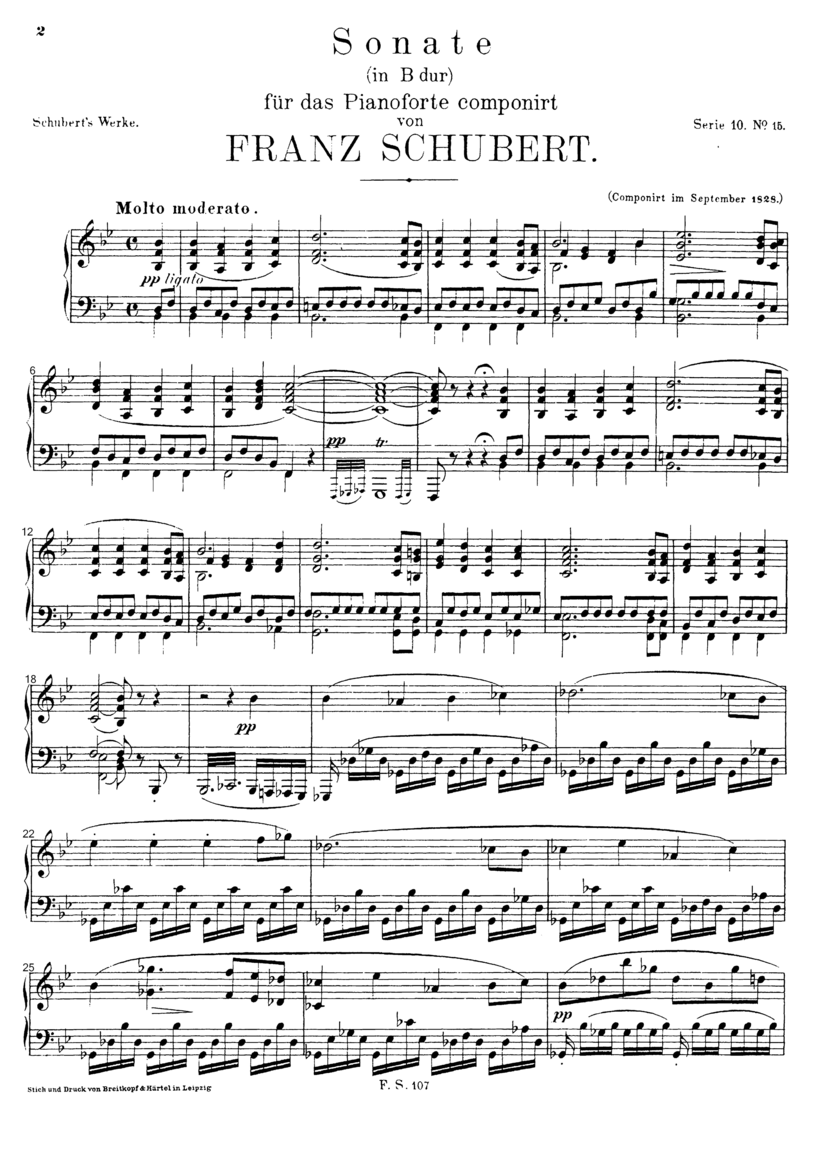

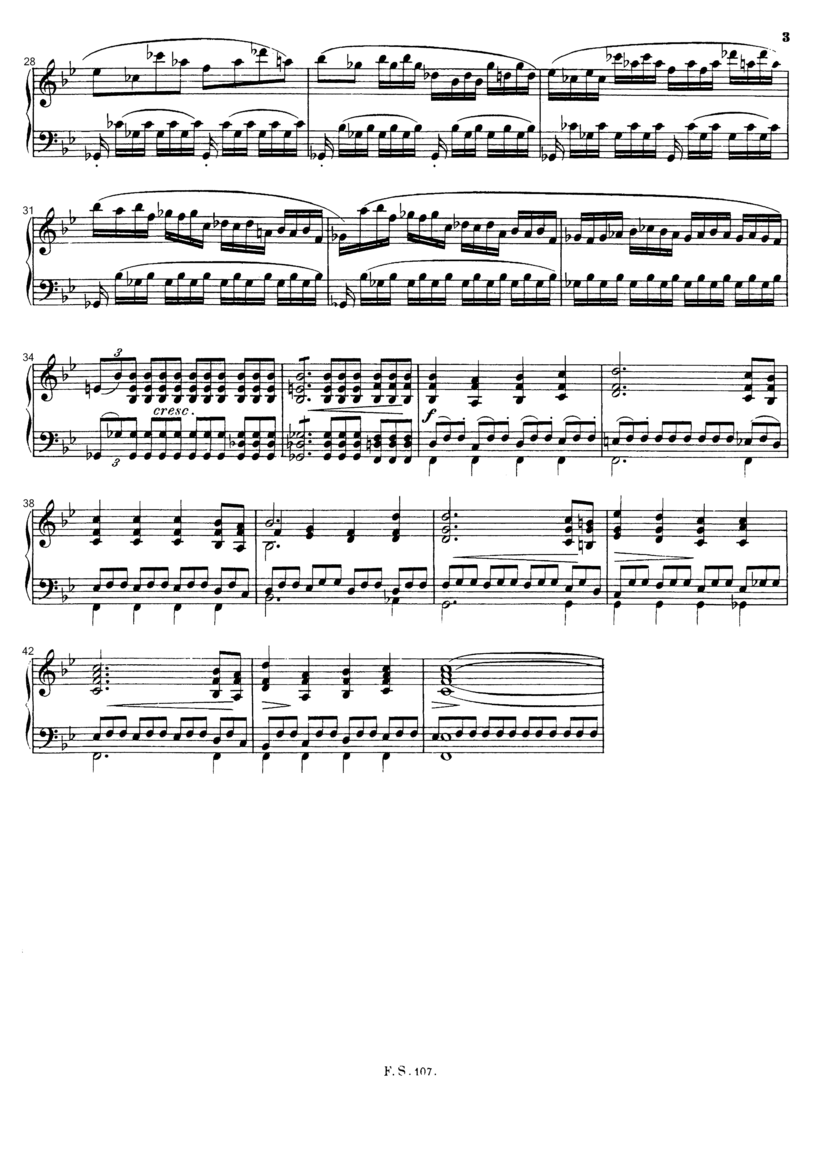

When I started this research, I worked very conventionally. I approached the musical works that I later used in my grounded performances as a ‘mainstream’ performer, respectful of the work and the traditions of musical interpretation and extracting from these works a great part of my artistic ideas. It all began with the Sonata in B-flat Major D960 by Franz Schubert. Having performed the sonata several times in diverse circumstances, including my master exam in historical keyboards and a concert shared with a noise improviser, I had a special relationship with the piece which included the sense that there was something odd about it. I wanted to find out what that was. Since I, at the beginning of this research, had no more than a vague question regarding the current relevance of musical works from the past, I started out by practicing the sonata again and again, dissecting its history and analysing its harmony and form like a ‘regular’ interpreter would. Progressively, associations started forming in my mind concerning issues of perspective, perception and the passing of time. Many of these associations emerged from my analysis of the piece. As Adorno (2005 [1928]) writes, Schubert’s music in general has a fragmentary character, unfolding without coherence or concern for the constraints of fixed form. Poetically, he (ibid, 9) suggests that the music grows like crystals, penetrating cavities, forming solid from liquid.

Everything in Schubert’s music is natural rather than artificial, this growth, entirely fragmentary, and never sufficient, is not plantlike, but crystalline. As the preserving transformation into the potpourri confirms the formerly configurative atomizations characteristic of Schubert – and through this the fragmentary character of his music, that makes it what it is – it illuminates Schubert’s landscape all at once.

What became apparent from my analysis of the sonata is that the formal treatment of its main theme gives it the fragmentary character. Yet the constant repetition of this theme gives it a luminous character as well, as suggested by Adorno. Repeated innumerous times throughout the first movement, the theme ceases after a while to be perceived as a centre and the movement’s protagonist; instead, it shines light on the figurations, rhythmical variations, motives, bass line, and harmonic modulations that surround it. Explained otherwise, although the many repetitions of the theme make listeners familiar with it, and although this familiarity ‘calls’ them to it, their attention shifts after a while to become more engaged with what takes place beyond, beneath or around it. For example, the theme’s presence alerts one to changes such as rhythmical variations in the eighth-note accompaniment in the middle voice between bars 1-18; the variation of the main theme in the melody, imitated by the third note of each four-note group of the bass accompaniment, in bars 20-26; and a doubling of the theme transposed a sixth-lower in the first note of each triplet of the bass accompaniment in bars 36-44.

In the case of the Study No. 5 (for left hand alone) after Bach's Chaconne, BWV 1016 by Johannes Brahms, I chose the piece first and foremost for its concision. After the experience of touchez, I was looking for simplicity so that I could better explore the metaxical amplification system. Additionally, its closed variation form reminded me of the partition mania of the 19th century, and especially its separation between art and the everyday. The piece, composed of sixty-four variations over a four-bar harmonic progression, recalls the secluded space of the concert with its fixed structures and familiar works, but one in which an infinity of emotions and sensations could be experienced. Harkening back to the issue of concision, what appealed to me was its left-hand line, unaccompanied, an elegant solution found by Brahms to evoke the solitary line of the violin. Dramaturgically, I was looking for tension. It seemed to me that this lone voice, in dialogue with amplified noise, would offer resistance to distraction, and sustain the focus of performer and audience more tightly than a complex, polyphonic work. Searching for this contrast and finding myself at the heart of the relatively large city of Porto, I decided to amplify the contextual element of ‘location’ by playing back the noise of the streets in the venue.

In a nutshell, and to finalise this study, interpretive considerations apropos the musical works were crucial for the development of artistic concepts such as the metaxical amplification, as well as for punctual decisions such as what to include in each performance and what to amplify. I would not have come to the idea of investigating the concert situation or of amplifying the performance environment without the Schubert sonata. Neither would I have been able to observe the impact of the amplification without the precision and dramatic force of Bach’s Chaconne as arranged by Brahms, pulling attention towards the musical work while at the same time engaging with the environmental noises. So, for my performances it mattered that I played this particular sonata and the study by Brahms. Each of these compositions conveys a particular atmosphere and has specific characteristics that have inspired me when conceiving the performances. Other works would have resulted in different choices, a different metaxical strategy and different outcomes. In this sense, these projects were very much the work of musical interpretation in the traditional sense of the term.

That said, the two pieces had a functional use in my grounded performances beyond their idiosyncrasies. I also chose them because they are symbolic objects belonging to the canon of classical music and associated with the introspective aesthetics of the 19th century that inspired silent listening practices. In other words, I selected them because they represent the particular period of the past in which the sonic apparatus that characterises today’s mainstream concert became a reality in public concert life. As I interpret these pieces, I perform their pastness or the past through them. When noise, an element so unwanted in the performance of such works, pours into the space and interrupts or interferes with the perception and interpretation of these works, their fragility is revealed. Through this fragility they reveal their pastness and a certain awkwardness in appearing in the present. When I interpret them, it feels as though I have a double role: that of a performer ‘of’ and that of a performer of the ‘of’, representing through the musical work the past and its attached traditions. I am aware of this double role: objectifying my practice has allowed me to distance myself enough to be able to observe and acknowledge the way this practice functions. Objectification was also the only way through which I could give up my interpretive control and let the environment play me. Within this context, the musical work ceased to be an abstract image or an unattainable goal, but an object of friction. Thence, bringing noise and work together in one performance signified for me the staging and resolution of the tension between two forces: tradition and conservation and the desire for change.

History in sound

Tradition is one of the most recurrent terms throughout this thesis and one that requires further elaboration. Tradition drives the field of classical music. To follow a tradition is a way of connecting with the past and legitimising a practice in terms of ‘how things have always been done’. As Foucault (1976, 21) writes: ‘[The notion of tradition] allows a reduction of the difference proper to every beginning, in order to pursue without discontinuity the endless search for the origin.’ What Foucault means to say is that tradition suggests a continuity between the past and the present despite the many changes occurring in an environment or field over time,absorbing or ignoring the many changes occurring in a given practice over time. In the case of some classical music performance practices, tradition feeds the illusion that there is a ‘right’ way of performing and that it issomehow possible to ‘restore’ a musical work as it was once imagined by the composer or as it was originally intended to sound. The Vienna Philharmonic, for instance, considers itself to be a ‘guardian of musical authenticity’ (Kenyon 2012, 17), because of its more than 150 years of existence, and hence its ‘continuous links to the sound world of Beethoven’s Vienna’ (ibid). The orchestra reflects the spirit of most conservatory trained musicians. Due to their education, such musicians come to embody, preserve and disseminate a specific cultural heritage. As Daniel Leech-Wilkinson (2020) affirms, these performers are trained to do ‘history in sound’. Shining through classical music performance is the legacy of the past, rather than the relationship between this past and the present. It is no wonder that Mauricio Kagel, in his film Ludwig Van, in which the music of Beethoven appears in myriads of contexts as disparate as streets or zoos, chooses the song In Questa Tomba Oscura (‘in this dark tomb’) for one of the few scenes in which Beethoven’s music is performed in a concert hall. Likewise, it should come as no surprise that when reading an article by the chief of the American National Archives Conservation Laboratory, Mary Lynn Ritzenthaler (2015, n.p.), on how to best conserve books, I associate many of the expressions she uses – terms such as 'careful handling', 'placing in boxes', ‘no exposure to sunlight’, ‘controlled conditions to avoid change' – with the way I dealt with musical works and with the secluded conditions in which I used to perform them.

When one refers to the performance of a musical work in a classical music context, it is generally assumed that the musical work is something that pre-exists the performance and is rendered audible by the performance (de Assis 2018). This definition of the musical work is considered Platonic, for it sees the musical work as an abstract object that only manifests itself imperfectly in the ephemerality of performance. Yet it is hard to say what the work is exactly in this definition. As de Assis (2018, 53) claims, what is being alluded to is most often an ‘image-of-work’, characterised by a number of ideas, sounds and references that one associates with a given work. Due to beliefs concerning the continuity of performance traditions and widely shared practices of musical interpretation, relatively stable images of musical works have emerged throughout history, giving them a certain objectivity. Schaeffer (2017 [1966], 97-98) speaks of a musical work as a peculiar ‘body’ that maintains both its aura and a recognisable profile independently of what is done with it:

Appalling instrumentalists or disastrous transmission can indeed “massacre” a classical work; but “massacred”, it nonetheless remains what it is, just as a mutilated body is still a body. […] We are not talking about disembodied music but about some highly developed forms of music, based on objects that are so perfectly understood, or at least so exclusively used as signs, that their realization in sound is, as it were, immaterial or at least secondary.

These two examples pertinently question the temporal dimension of music. While most of the pieces performed on these occasions had a pre-defined temporal structure with a beginning-middle-and-end, very few visitors sat down or paused to listen to the works in their entirety. To use an expression by Peter Szendy (2008, 104), the way they listened, in relation to the works’ structure, was ‘lacunary’. Szendy (ibid) praises this ‘lacunary’ mode, which proposes an alternative to Adorno’s structural and synthetic listening (see Chapter One), which he finds too absolutist:

Now, according to Adorno, […] we have only the expert face-to-face with the representatives of an increasingly fallen listening, until music becomes pure ”entertainment”. “The tendency today”, writes Adorno, “is to understand everything or nothing”. […] with the notion of a work as Adorno presupposes it, we are necessarily led to this alternative: either to understand/hear everything (as it is, without arrangement being possible), or to understand/hear nothing. Perhaps most surprising […] is the absence of one possibility, as ”theoretical” and quantitatively insignificant as it may be: namely, that distraction, lacunary listening, might also be a means, an attitude, to make sense of the work; that a certain inattention, a certain wavering of listening, might also be a valid and fertile connection in auditory interpretation at work.

In this passage, Cook opposes the notion of script to what he calls a practice of reproduction. This practice is based on the idea that performances are supposed to be no more than the realisation of the original vision of the work. In contrast, in contemporary theatre, many practitioners have an unfettered way of approaching classical texts, using them as a source of inspiration rather than as something one ‘does justice’ to, and therefore not hesitating to alter or leave out parts to suit their conceptual needs. In fact, since the 1960s, a theatrical orientation known as postdramatic theatre has been reconfiguring the relationship between staging, performance situation and text. The prefix post- in ‘postdramatic’ indicates a rupture with the traditional relationship of theatre to drama (Lehmann 2006, 2). This also contained a rupture with the classical tradition of staging or mise en scène, usually concerned with complementing and giving physical shape to the intentions of the author and the context of the original text of the play, also known as the primary text. In postdramatic theatre, however, the focus is on the so-called ‘performance text’, comprising the 'whole situation of the performance' (ibid, 85). This means that staging is no longer subordinated to the primary text but considered a point of departure for the realisation of a broader theatrical project. When Cook speaks of script, he is referring to the possibility of the musical score becoming, as Lehmann (2006, 32) writes, 'a beginning and a point of departure, not a site of transcription/copying’.

In an essay about Carmelo Bene's stagings of Shakespeare plays, literary scholar Fernando Cioni (2018) differentiates between rewritings and adaptations of the primary text. ‘Adapting’ a text doesn’t mean that the original (perceived) meaning of the work is modified, although there are linguistic alterations, cuts or addition of scenes and speeches (ibid, 164). This form of adaptation is generally meant to give a more contemporary note to classical texts and corresponds to what Hermann Danuser (1992) has theorised in music as an actualising mode of musical interpretation. Characteristic of the actualising approach, more popular in post-WWII theatre productions than in music, is indeed a need to make the past understandable and more palatable for today’s audiences. To convey the expressive intentions of the composer, performances should transcend the physical conditions available to the composer. Therefore, the performers who defend such views do not hesitate to adapt the text at their own discretion, to change instrumentation or other artifices. Glenn Gould’s recording of the Goldberg Variations, with its extensive use of new recording techniques to project articulation and highlight specific structural elements, is a good musical example of this type of practice. ‘Rewriting’ a text, on the other hand, is a more inventive activity consisting in intervening in the text from a particular ideological standpoint (Cioni 2018, 165). Rewriting also means de-historicising a text or contraposing it to other texts, in which case the text becomes the starting point for an entirely new creation. The intention behind such transformation is often of a critical nature, either with regard to the content of the original text or in relation to the conventions of theatre and canonical expectancy. As Cioni (ibid, 163) explains: 'In contemporary theatre, as in culture at large, the classics are updated, modernized, in order to free them from a static and inviolable literary tradition, which has been appointed (chosen as) the simulacrum of Western culture. The creative act [...] becomes a critical act'.

Comparing Cook’s idea of script and the ontological reconfiguration proposed by ME21, I find the latter inspiring as a method, especially for performers wishing to experiment beyond their usual practice. Still under the pretext of performing a work, the performer can explore different media and operate scenographically and compositionally, deciding how to organise these media in space and time. In a sense, the role of the performer comes closer to that of music theatre directors or curators, in a performance in which they may or may not play their instrument, all depending on what they decide to include in their image-of-work. Similarly, Cook’s idea of scores as scripts is attractive and even closer to my grounded performances because it makes performers more mindful of and engaged in aspects of the performance other than just the work. As with Rasch, Cook suggests performers should think like scenographers, dramaturges or theatre directors. They should no longer be focused solely on the work but instead consider a larger context, including space, the presence of the audience, movements, lighting, and perhaps even environmental sounds. The redefinition of the work and the score, then, entails a redefinition of the performer’s modus operandi. Yet, although these considerations did inform me in the conception of my performances, I hesitate to embrace the idea of redefining work and score, for even though considering the score as a script reconfigures and expands the preparation process as well as the performer’s awareness of the physical situatedness, it does not necessarily entail more openness and spontaneity during the performance itself. They remain prepared, rehearsed, and with a fixed end. Besides, in Rasch in particular, the absence of the ‘of’ removes the element of friction, so that one can experience the performance as too one-dimensional. The historicity of the materials, and the constant allusion to the Kreisleriana, allow the sensation of being in a museum rather than problematising the definition of the work. Instead of Goehr’s ‘imaginary museum of musical works’, it created a beautiful and poetic museum of imaginary musical works.3

Taken together, these examples are illustrative for the way in which the musical work is considered within a context, instead of an autonomous and self-sufficient entity that should be heard in-and-of itself. In each case, the work becomes a pretext for the exploration of the performer’s personal sound world, of historical and associative perspectives, of the sociality of the performance event, of alternative modes of listening and artistic spaces, and of the performance environment itself. Each time, the insertion of the work into a different context informs and transforms the performer’s practice and the perception of the work. Experiencing the performance is no longer centred on the realisation and reception of the work, but, rather, on its situatedness, including the interactions between various agents, and the relations that audience and performers draw from these interactions. This is certainly the most essential way in which these examples inform my own work, to which I now return by looking back at the process that led me to the notion of metaxical amplification and its implementation in grounded performances (see Chapter Two), and by investigating the changing ways in which I, during this process, related to the ‘of’.

Performers usually derive their ‘image-of-work’ from the musical score, which is considered a concrete pillar upon which to ground the performance. This solidity attributed to the score has to do with the fact that, in a practice concerned with the past, the score stands out as having a certain objectivity, a material element that most substantially connects the performer to the composer's original intentions. And in a sense, this is also true. If we follow Derrida’s claim that language is always already writing (interview with Derrida in Stiegler 2002 [1996], 162), then a composition cannot be considered as a free-standing idea in the mind of the composer; it is already imagined in relation to the possibilities offered by musical notation, and realised in and through notation. In this perspective, score and work coincide. The objectivity imputed to the score is also understandable, especially when considering the overall evolution of musical notation in the last centuries. For a long period, musical notation was more of a shorthand system that musicians knew how to decode and complete, whereas throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the essence of the work became more codified in the score in terms of dynamics, expression and rhythm. The idea of a ‘base’ emerged – a clean, objective version of a piece which a performer could spice up within adequate limits. Also, while the popularity of performing from scores annotated by great musicians and experts had endured, in modern times the ‘Urtext’, or ‘text of the origins’, as Dorian (1996, 224) translates it, became the only dependable source for a reliable interpretation. Nowadays, classical musicians are most often trained to consider the score as a stable and fixed category, governing performance as an 'intelligent measuring device' (Orning 2014, 287), and allowing listeners to measure its correctness. On this note, Cobussen (2017, 111) formulates the traditional definition of the score as ‘an authoritative or a coded grid, mainly designed to facilitate unidirectional instructions from composer to performer’. Carolyn Abbate (2004, 508) refers to this tradition as ‘human bodies wired to notational prescriptions’.4 In sum, musical notation since the classical period has been considered as a prescriptive and binding script, and its importance remains largely undisputed. This despite the growing tendency to question both the objectivity and the reliability of received traditions, which are being replaced by perspectives, or interpretations, on and of a musical score.5

When one operates with this definition of the musical work – the definition used in this study until now – one usually aims at a certain degree of fidelity towards the score and the work, varying from total to relative. Goehr (1996, 6) distinguishes for instance between ‘a perfect performance of music’ (PPM) and a ‘perfect musical performance’ (PMP). A perfect performance of music takes the ‘of’ seriously by considering the musical work as more important than its impact on the listener or the social aspects of a performance. What counts, in a performance, is the ‘thorough understanding of the work’ (ibid, 7) in the structural sense of Adorno, as discussed in Chapter One.6

Indeed, returning to the various degrees of being truthful to the work, there are few examples of artistic projects which intervene directly with the practice of the performer and their relationship to the score. Intervention, as I would like to understand it here, also refers to indirect involvement, through the way artistic projects experiment with the modalities of musical presentation. An example is Liquid Rooms by Ensemble Ictus, a performance-concept which places equal focus on the music as on the social dimension of performance. Conceived as informal and relaxed performance situations inspired by rock festivals and improvised gigs, Liquid Rooms is intended for those not familiar with the strict rituals of the traditional classical concert. In the version that I visited with a non-musician friend in Berlin in 2015, contemporary works were performed for several hours on a series of stages placed in different parts of the concert hall. Blackouts, strobing effects, projections and other extra-musical elements ensured a smooth and unbroken transition between stages and musical works, and the audience was invited to move freely within the concert space, entering or leaving at will. Another example that emphasises the ‘eventness’ of performance is the site-specific project Kunsthalle for Music. Here the curator-composer Ari Benjamin Meyers displaces musical performance from the concert hall to a so-called white cube – an art gallery space characterised by its neutrality, bright lighting and light-coloured walls. For this project, which I visited at the former Witte de With Centre for Contemporary Art in Rotterdam in 2017, Meyers selected a group of musicians who performed in the museum each day, all day, for the duration of the show. The white walls were left empty except for signposts indicating the title of the piece to be performed on that spot. Other than that, the musicians did all the work, alternating performances in the different rooms of the museum, playing solo, in small groups or as a whole ensemble. Since the performances were unannounced, the audience had to move around the rooms and follow the sounds to find out where to go and what would happen next. By displacing musical performance from the concert hall to a white cube, Meyers created a structure that would allow music to be produced and heard in accordance with the rules of an art gallery or museum. As such, in a white cube, people are supposed to walk, as is suggested by the partitioning of the space into several display areas, so if visitors at times sat down to enjoy a particular performance, it was a matter of choice.

To sum up, artistic projects like Kunsthalle or Liquid Rooms, by reconfiguring the concert hall environment and ‘installing’ musical performance in a non-musical environment, problematised time as a decisive musical parameter. How you deal with the temporal dimension of music determines how you will understand music. If aperformance does not create the optimal conditions for focused listening, the symbolic time of music is experienced differently. Instead of perceiving a closed structure composed of parts forming a whole, the focus of the listener is on isolated passages and fragments. So, even though musicians perform the works in a conventional manner, the way the works are presented affect the way they are perceived. These types of musical performances arouse interest because they incorporate rituals and listening modes that are admittedly more suitable to acontemporary habitus; they also offer new understandings of music as a temporal phenomenon. In what concerns the musicians, although neither the Kunsthalle or Liquid Rooms interfere with their practice in a substantial way, one could imagine that the popularisation of peripatetic reception practices will interfere over time with and transform more traditional performances. It might for instance no longer make sense to practice entire works or concentrate on defining their form and the relations between their parts when these are going to be heard in a fragmentary, or lacunary, way.

In contrast with these approaches, which demonstrate different levels of engagement with or resistance to the authority usually attributed to the musical work, there are yet other proposals. These outmaneuver the weight of the ‘of’ more fundamentally by redefining the very concepts of work and score themselves. One such maneuver comes from the artistic research programme MusicExperiment 21 (ME21), with which I was associated between 2014 and 2017. ME21 sought to expand the traditional ‘image-of-work’ to include related scores, sketches, editions, renderings, recordings, philosophical texts, reviews, and films, among other heterogeneous materials. These materials were used by the group in experimental settings by overlaying instrumental performance, texts, images, electronic sounds, voice, and so on. In these constellations, the score became but one of the materials that constituted the work. The musical work was no longer regarded as a closed and abstract entity, at least partlyencoded in a score that would determine its acoustic realisation, but as a potentiality which could be actualised by the performer in an infinite and indeterminate number of ways and media. As de Assis (2018, 40), the group’s principal investigator, explains:

Situated beyond ‘interpretation’, ‘hermeneutics’, and ‘aesthetics’, the Rasch series is part of wider research on what might be labelled ‘experimental performance practices’. Such practices offer a tangible mode of exposing musical works as multiplicities. On the contrary, if one sticks to a traditional image of work based upon the One (or Idea), one has necessarily to stick also to notions of ‘work concept’, interpretation, authenticity, fidelity to the composer’s intentions, and other highly prescriptive rules that originated in the nineteenth century. […]. What I mean is that every musical practice, every way of doing performance depends on, or is the direct result of, a specific ontological commitment. If one’s goal is the passive reproduction of a particular edition of a musical piece from the early nineteenth century, one is indeed better advised to remain within the ‘classical paradigm’, with all its associated practices of survey, discipline, and control. But if one is willing to expose the richness of the available materials that irradiate from that piece, one has to move towards new ontological accounts.

De Assis implies that the way one chooses to perform a piece depends on one’s conception of what a musical work is. The Rasch-series consisted of a superimposition of materials associated with Robert Schumann’s Kreisleriana op.16, including music, texts, images and voices. By navigating the different layers of materials, the audience is always gaining new perspectives on the musical work being thematised in the performance. These shifting perspectives block the synthetic effort of the listeners as they attempt to encapsulate the piece in one comprehensive experience. As a result, the image of the work remains open. Kreisleriana cannot be defined as a particular musical work, but rather as a piece in a universe of ‘things’ associated with the idea of the work.

Rather than expanding the concept of the musical work to integrate different elements, Nicholas Cook likes to open up the musical score. Inspired by theatre and performance studies, Cook proposes to look at scores as scripts rather than as prescriptive documents. In theatre or film, scripts are unfinished by nature and completed by the many people involved in the production of a performance. That being so, scripts emphasise process and open-endedness, whereas a score tends to represent a fixed product or structure that performers are required to reproduce.

Whereas to think of a Mozart quartet as a ‘text’ is to construe it as a half-sonic, half-ideal object reproduced in performance, to think of it as a ‘script’ is to see it as choreographing a series of real-time, social interactions between players: a series of mutual acts of listening and communal gestures that enact a particular vision of human society […]Musical works underdetermine their performances, but to think of their notations as ‘scripts’ rather than ‘texts’ is not simply to think of them as being less detailed. (As I mentioned, performance routinely involves not playing what is notated as well as playing what is not notated; in this sense there is an incommensurability between the detail of notation and that of performance, so that notions of more or less are not entirely to the point.) Rather, it implies a reorientation of the relationship between notation and performance. The traditional model of musical transmission, borrowed from philology, is the stemma: a kind of family tree in which successive interpretations move vertically away from the composer’s original vision. The text, then, is the embodiment of this vision, and the traditional aim of source criticism is to ensure as close an alignment as possible between the two, just as the traditional aim of historically-informed performance is to translate the vision into sound […The] shift from seeing performance as the reproduction of texts to seeing it a cultural practice prompted by scripts results in the dissolving of any stable distinction between work and performance. (Cook 2001, n.p.)

Furthermore, the absence of pointed rhetorical figures and transitions between the renewed appearances of the theme gives the impression that these appearances are purely accidental. Therefore, when listening to the sonata, I can feel like a passenger on a train driving through tunnelled railways who, in-between these tunnels, is surprised by the ever-changing landscapes. This is most like my experiences of recurring memories and passing thoughts that connect to other thoughts or disappear without me knowing how or why. In this light, my experience of the piece acquires an existential dimension, reflecting a certain contingency, which is possibly why there is a certain melancholy in several descriptions of this sonata, something about fleetingness and vulnerability, entwined with openness and surprise. However, as Adorno says, it is not easy to find a story in Schubert’s instrumental music, to really guess what the piece is about. The logic of Schubert is neither programmatic nor psychological. I noticed, in fact, that when searching for concrete topics that could be collated with the sonata, nothing stuck – the piece might be about nothing, really. Instead, and this is my own interpretation, it articulates perceptions; perhaps it is even self-referentially commenting on the act of perceiving. Therefore, looser concepts of perspective reversal, time, modes of sensing and images of changing and ever-expanding landscapes established themselves as key themes that could be worked on further in my decoding of the sonata.7

In a conceptual phase preceding the invention of metaxical amplification, working with photographer Karen Stuke,composer Erik Dæhlin and scenographer Tormod Lindgren, some of the first ideas that came up during our talks were formulated in relation to these themes – reversal of perspective, the passing of time, modes of sensing and changing landscapes. In the notes from our meetings, I find references to open-endedness, and the suggestion to build a rotating platform that would present the pianist to the audience in ever-shifting angles. There is also the idea of transposing the imaginary topography of the piece (its open landscapes) to the physical space of the performance, for instance by avoiding an illuminated centre or fixed seating positions in favour of creating a wandering space – very cliché in the context of Schubert but for a good reason. Whereas open-endedness and a wandering space were implemented in the final performance, the rotating platform was considered counterproductive to the intention of decentralising attention, since it would have required a centralised stage. Nevertheless, what stayed in my mind was the idea of rotation and the multiplication of perspectives that would come along with it. As my first intention of creating a music theatrical performance around the sonata progressively gave way to an interest in exploring the concert situation and its auditory landscape, this initial idea metamorphosed progressively into the idea of a system that would make one hear a familiar situation with new ears.

Reflecting about what moves artists today, art theorist Boris Groys (2008, 71) concludes that contemporary art is about ‘the act of presenting the present’. He explains: ‘What differentiates contemporary art from previous times is only the fact that the originality of a work in our time is not established depending on its own form, but through its inclusion in a certain context, in a certain installation, through its topological inscription’ (ibid, 74). Included in a larger context, an artwork may enter into dialogue with this context, transform it and be transformed by it. This idea of art becomes manifest in the work of many classically trained performers within the classical and contemporary music field. These performers no longer treat musical works as autonomous entities, but as pretexts for differentiated experiences, engaging listeners and themselves in the present and at times even beyond the purely sonic realm. Disregarding the autonomy of musical works and submitting them to possible transformations does not go without saying in a practice that to this day has been largely oriented towards preservation. It requires both courage and a critical distance to the tradition, as well as a retraining of previously hard-wired habits and assumptions. In what follows, I explore different ways in which performers might relate to this tradition, by looking back at the process of creating and implementing my grounded performances, and considering related works and thoughts by other musicians that have directly or indirectly contributed to this process. Of particular interest to me in this final chapter is to observe how, when performers consciously deviate from this tradition, their choices reflect tendencies or intentions for the future of their practice.