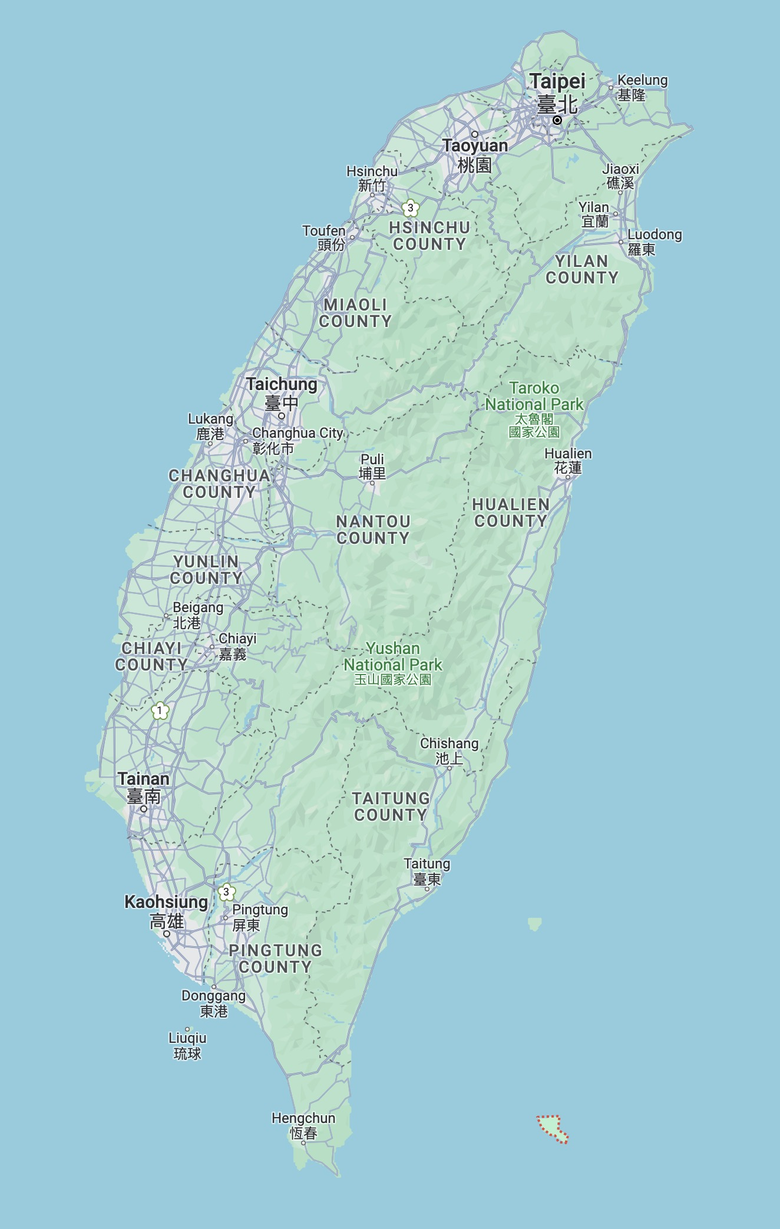

This exposition showcases the artistic research project Creative (Mis)Understandings: Methodologies of Inspiration (2018–2023), a collaboration between sound makers, composers and performers from an indigenous community in Taiwan (the Tao, living on Lanyu [‘Orchid’] Island) and from Europe. Since 2005, violist Wei-Ya Lin (who is also an ethnomusicologist) and Johannes Kretz (a composer specialising in electronic sound production) have been making regular visits to the Tao community on Lanyu Island, Taiwan. They document songs, conduct interviews and seek to understand the connection between singing and the lives of the Tao people (Kretz 2007a, 2007b; Lin 2015b and 2021). This has led to various (artistic) research projects (Lin 2016; Lin and Kretz 2019) and to Wei-Ya Lin’s dissertation (2015b, 2021).

For example, in 2016, this collaboration resulted in an evening-length dance theatre production entitled Maataw – The Floating Island, which premiered at the National Theatre in Taipei. This production not only showcased the beauty of Tao life, dance and music but also placed a strong, critical, emotional and political emphasis on their social, economic and ecological concerns. Around 10,000 people attended the performance. Issues such as the nuclear waste facility on Lanyu Island, established through a scam that tricked the Tao people into believing it would be a ‘fish can factory’, were brought to the attention of a wider audience and likely even triggered a debate in the Taiwanese parliament (see Lin 2016 for details).

After years of exploration, frequent fieldwork and political activism, we began asking ourselves how we could support the sustainability of both Tao culture and the culture of so-called avant-garde composition. It was time for research on the knowledge embedded in traditional Tao songs, the potential for transformation and preservation, and the possibilities of leaving our comfort zones to join the forces of both non-mainstream cultures.

Thus, in this project, we reflect on the term inspiration and redefine it as ‘mutually appreciated intentional and reciprocal artistic influence based on solidarity.’

Starting Points: the Tao

In August 2018, before the Creative (Mis)Understandings project began, Wei-Ya Lin conducted interviews and initiated dialogues with several Tao cultural workers and schoolteachers from both younger and older generations. All of them expressed concerns about the ongoing loss of language and culture in their society. They felt that the pace of this loss was accelerating rapidly in recent years. Following these discussions, Lin conducted a survey with 65 secondary school students on Lanyu Island, aged 13 to 15, about their knowledge of traditional song repertoires and singing practices. Only 24 students could name some children’s songs and/or well-known love songs and none of them could understand the lyrics of songs in the ‘older language’ (used in Mikariyag or Raod songs). This insight became crucial for the project team’s considerations throughout the entire project period.

The Tao have an oral tradition, and traditional singing practices are among the most important cultural practices in their community. In the past, songs transmitted knowledge about how to sustain their living environment; regulate social, economic, and ecological relationships; and pass on individual experiences and collective history (Lin 2021). In this sense, the traditional songs functioned like books, serving as a medium for storing and transmitting knowledge from generation to generation. However, today, many young Tao people are not proficient in their native language, and traditional singing practices have been almost abandoned – largely because they simply do not like the sound of these songs.

For these reasons, the project team identified an urgent need to support the sustainability of the Tao language and culture. They came up with the idea of transforming traditional songs into new artistic forms, creating innovative ways to transmit the traditional knowledge and histories stored in the songs to future generations.

Outline

Today, many traditional musical practices face the threat of disappearing in the near future. In the Music Vitality and Endangerment Framework (Grant 2016), both contemporary academic composition and traditional Tao singing practices are listed among endangered traditions, along with many other non-mainstream practices. This project was an effort to join creative forces and support solidarity between (artistic) minorities in the broadest sense, ranging from traditional music to academic composition. The aim was to support these practices and gain relevance in a world dominated by commercialised cultural life while redefining aesthetic and social categories.

The project addressed two key issues: first, the issue of a certain elitist tendency in European art music (Paddison and Deliège 2010) and, second, the fact that non-academic musical knowledge is often either ignored or exploited for compositional inspiration (WIPO 2001). The artistic and scholarly interactions in this project – promoting dialogical and distributed knowledge production in musical encounters – were organised in four phases:

1. The Initial Exchange: This brought together artists and artistic researchers from Europe and the Tao community in Vienna for their first exchange, while structuring further artistic and research collaborations.

2. The Artistic Research Platform: Throughout the project, we maintained a platform for artistic research and exchange, including workshops for collaborative artistic creation and reflection on creative processes. Regular online meetings were also held to ensure that our Tao team members could easily participate in discussions.

3. Fieldwork on Lanyu Island: All the European team members participated in fieldwork on Lanyu Island, a region characterised by both historical and political challenges and a rich cultural overlap.

4. Evaluation and Dissemination: The final evaluation and dissemination of the project results took place in Austria, Hungary and Taiwan, involving feedback and continued interaction with the fields and communities touched by the project.

In all the phases, the ‘friction’ between the rigor of research – aiming for objectivity – and the artistic approaches that embrace playful freedom, creative (mis)interpretation, irony and humour proved extremely fruitful for progress on all sides. By emphasising the reciprocal nature of inspiration, we encountered creative (mis)understandings – a concept highlighted by the renowned composer Brian Ferneyhough (Stobart and Kruth 2000: 4) and used to describe the productive mutations or distortions of artistic content. These understandings and misunderstandings resulted in socially relevant and innovative methodologies for creating and disseminating meaningful music.

Encouraging artists and artistic researchers to step out of their comfort zones and participate in a ‘culture shock laboratory’ – or to engage in a process of transculturation (Ortiz 1940) – helped them renew their perspectives and fostered creative (mis)understandings through extended methodologies. This led to exciting new forms of collaborative creation and performance, offering fresh perspectives on contemporary music to a diverse range of audiences, especially to social and artistic minorities.

The combination of scholarly methods, which aim to understand ‘otherness’, and artistic methods challenged all the participants to engage in a mutually rewarding dialogue – one that we believe is urgently needed (Kretz and Lin 2021).

Starting Points: The European Academically Trained Sound Artists / Composers / Performers

The collaboration explored various ways to transform traditional songs in order to preserve and convey the knowledge contained in them, while also shedding new light on what it means to create something ‘new’ in the European context (Kretz and Lin 2021).

In academic and Western avant-garde composition, there is growing scepticism and concern that these approaches are becoming increasingly elitist, catering to a very niche audience. As a result, the question of reconnecting life and art in meaningful ways and examining the role of musical practices in our daily lives has become increasingly important for numerous academically trained composers and sound artists.

Moreover, the growing understanding of the world as a globalised space has led to art practices that aim to decolonise the world of art (Böhler et al. 2022). Many composers from academic Western backgrounds are showing interest in and seeking inspiration from other musical traditions around the world. However, these efforts often remain superficial. Instead of delving into the deeper cultural context and developing a meaningful understanding of cultural elements, instruments and practices, cultural exchange often remains limited to transplanting certain aspects or elements to achieve a superficial effect of exoticism (see Bhagwati 2013).

In this sense, the presented project aimed to serve as a paradigmatic endeavour, demonstrating how methods from ethnomusicology, repeated fieldwork, co-creational practices and long-term discourse can lead to more authentic and intrinsic exchange and interaction. The goal was not only to produce a few interesting musical results but also to provide a model of transcultural artistic research, which could be useful in other contexts and situations.

A key driving factor behind the project was the recognition that both traditional Tao music practices and Western avant-garde music are endangered. The collaboration sought to unite these fields, joining their forces, offering promising potential benefits for both sides.

go to Methodology

go to Example: The Tao Classroom

go to Example: Scalable Compositions

go to Closing Presentation: Conclusions

go to The Team

go to Literature

go to List of Presentations

Research Questions

1. How can artistic research contribute to strengthening/encouraging certain music traditions which are at a disadvantage due to power relations in the context of modernity and music industry? Which strategies for transforming traditional songs can bridge generations and inspire new forms of expression while still preserving traditional knowledge and wisdom?

2. What does it mean to create something new in the right time and format? How can art creations relate to social responsibility? Instead of continuing artistic innovation in a one-directional way, can we develop collective creation cycles with feedback loops, aiming for socially relevant forms of expression?

3. Can we create art that is adaptable for different contexts? Can the concept of a scalable composition open up access to different audiences and peer groups?

The Aims of the Project

The project aims

1. To support and revitalise sustainable cultural practices among the Tao.

2. To explore alternative approaches by taking Euro-American academically trained composers and artists out of their comfort zones and exposing them to different ontologies and epistemologies.

The artistic research project Creative (Mis)Understandings: Methodologies of Inspiration (2018–2023) is financed by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) and hosted at the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna (mdw). Johannes Kretz and Wei-Ya Lin lead this project together.

Philosophical Foundations

The project anchors the notions of ‘music composition’, or ‘sound creation’, and composition within contemporary philosophical and anthropological theories. These theories highlight the diversity of reality constructions, including artful representation and practice (including music). On the one hand, ontologies – that is, forms of knowledge about what exists and the ways in which the existing interrelates – are diverse among human societies (Descola 2013). In such diverse societies, the meaning and function of sound and music (and other arts) are understood in quite different ways. As the contemporary ‘globalising world’ tends to overemphasise the ontology of naturalism, other forms of knowledge should be fostered and promoted in order to maintain a balance. On the other hand, the idea that knowledge about the world and about arts is consistent within a certain geographical or cultural space is being challenged. Bruno Latour (2013) shows that ‘the moderns’ (human beings localising themselves in a naturalistic world) do not live in one reality but make use of a multitude of ‘modes of existence’. Therefore, if one tries to understand what music is – and what music can be – one should develop the ability to switch perspectives: it is the perspective that determines the body that perceives the world (Viveiros de Castro 2012).

In the Western world – that is, in naturalist collectives (Descola 2013) – the fundamental epistemological paradigm is the scientific method: a claim to knowledge has to be verified by inter-subjectively applicable means (experiments, theoretical validity, reliance on previously proven sources). The methods for doing so are diverse and differ between academic disciplines or, more precisely, between epistemic cultures (Knorr-Cetina 2007); but still, most of the accepted methods are variants of visualisation and writing. However, knowledge production can follow different paths (Feyerabend 1975, 1994, Blake 2015)4 and, as the new field of sound studies asserts, it is also present and representable in the sonic domain (Brabec de Mori and Winter 2018).

In both scientific and artistic knowledge production approaches, it is crucial to reflect on the differentiation between explicit and tacit/implicit knowledge (Polanyi 1967; Collins 2010). Whereas explicit knowledge embraces what is uttered, written and communicated, the tacit/implicit dimension often takes on the quality of the pre-supposed and is embodied through practices (Reckwitz 2002) or – what is most relevant for our project – uses other sensory domains than that of visual sense: it may manifest as auditory knowledge (i.e. it is embodied as knowledge tacitly comprehended in sound) (Zembylas 2016; Zembylas/Niederauer 2016). Falling beyond the analytical grasp, auditory knowledge can only be expressed through the non-verbal variability of sonic expression, through what we include in the term music. Both musicians and researchers can offer valuable contributions to reality constructions, that is, to how we perceive and understand our world and how we relate to and interact with both other humans and our environment (Brabec de Mori 2016).

The methods that will be applied in the proposed project depart from ethnographic evidence that people living in non-Western or traditional societies often use methods of knowledge production within the sonic domain that are commonly unaddressed or unknown among contemporary music composers (aside from exoticist appropriations). To understand such traditional knowledge production – conceived as changeable reality construction – we propose creating a framework to develop sonic creations as knowledge production. Therefore, at the core of our undertaking lies a dialogue of sonic reality constructions, accompanied by verbal reflection (Huber, Ingrisch, Kaufmann et al. 2021).