3.1. Performing patches and tape machines

As usually happens during a creative process in a recording studio, the affordances of the tools and devices that are available and how they are used for music-making play an integral role in the final result. In order to see what kind of effect these affordances would have on my music, I decided to come as close as possible to the “limitations” (by today’s standards) offered by the technologies and workflows used in the 1960s. For this reason, I took advantage of the voltage-control studio in the Institute of Sonology in The Hague (as mentioned earlier) and the unique combination of analogue modules and tape machines it provides.

Initially, I started designing patches which would be “performable” in a sense that several parameters could be manually changed (or affected by other procedures) in real time. In other words, I set out to create a number of compositional rules which I would then explore creatively. As Thor Magnusson points out when commenting on Suzanne Ciani’s “Basic Performance Patch” designed for a Buchla Series 200 modular synthesiser:

Ciani designed a patch, which is a process of composition, and then she goes on to describe musical ideas that “evolved as a result of working with this patch”; in other words, the patch is about forming the research field and setting the boundaries of thought and expression, but then it takes time and engagement to explore the ergodynamics of the patch, and get to know the system, perhaps similar to how a dancer begins to know their dancing partner (Magnusson, 2019: 118-119).

This would also reflect the improvisational way in which sometimes rock musicians would approach the recording studio - exemplified by how the Beatles created the sound collage piece “Revolution #9” by “live-mixing” several running tape loops (at different playback speeds and either direction) in the studio, with material taken from EMI’s tape library (Ryan & Kehew, 2006: 304-305; Everett, 1999: 174-175).

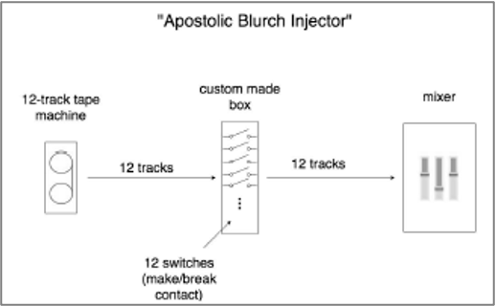

One of the patches I did was inspired by Frank Zappa’s DIY technique to achieve the sound collages in the tracks “Nasal Retentive Calliope Music” or “The Chrome Plated Megaphone Of Destiny” amongst numerous other cases in his early albums with the Mothers of Invention. This was done partly by splicing pieces of tape and partly by using the “Apostolic blurch injector” [5]: a custom made hardware device (built by a studio technician) which allowed him to switch between each output of a 12-track tape machine in a more improvisational way and at the same time being able to record the result through the mixing desk (see Figure below).

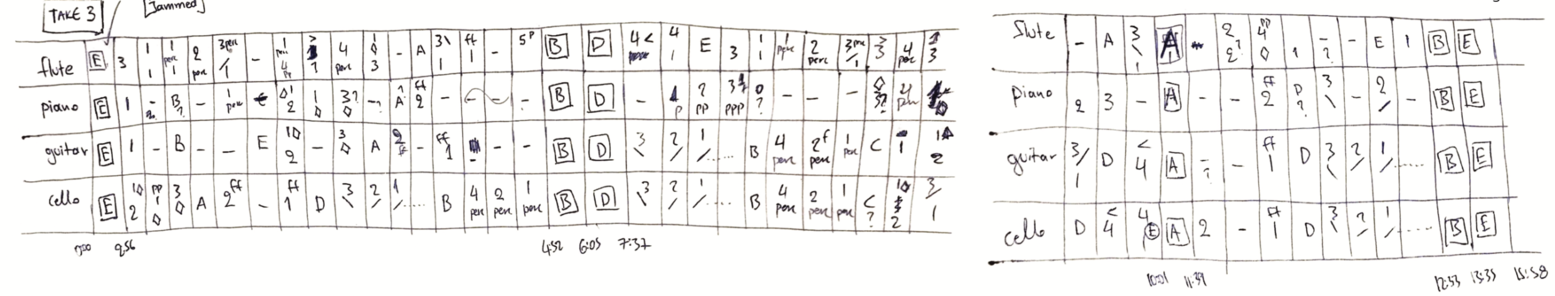

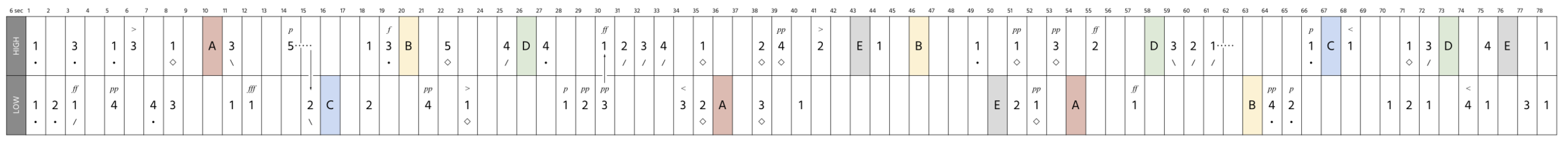

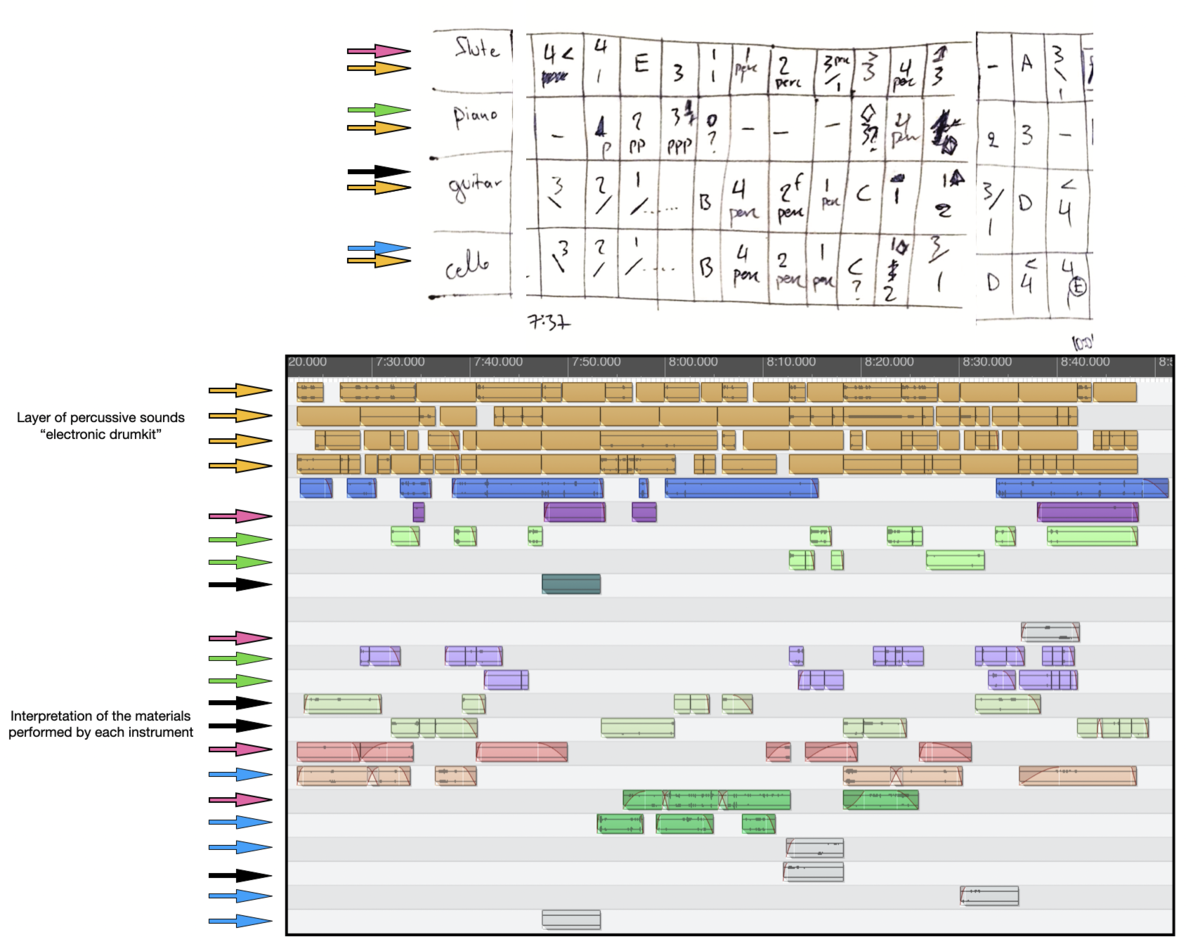

As we can see in the graphic score above, the improvisers are asked to follow a two-part grid, indicating high and low registers; number of sounds to be played in each six-second bar; articulations and “playing modes” represented by symbols and letters respectively. Each playing mode corresponds to a technique or instruction whose interpretation is completely left to the musicians: A=loop, B=long sound, C=improvise between c and d#, D=grains, E=free improvisation. When cued to be performed (usually by a conductor), they function as “points of focus” which the musicians have to remain until cued to stop. Once the end cue has been given, players can choose the point in the score they wish to continue from, provided that it is after a mode identical to the one they just finished. This creates a variety of possibilities where parts of the score can collide with each other depending on the conductors’ and musicians' decisions. The total duration of the performance is decided by the conductor.

On 20 March 2022, three takes of the score were performed and recorded in the New Music Lab at the Institute of Sonology (Royal Conservatoire, The Hague). The ensemble was "conducted" using visual cues projected on two screens in front of the players. With this setup, I was able to shape the performance in real time, with very little influence over the sound material being generated (see Figures 1 and 2).

jammed (take 1, excerpt)

In the short excerpt above we can hear how bars 1 to 16 were performed and recorded during the first take. It is clear that I wasn’t after a strictly precise performance of the articulations, dynamics and timings. Instead, I asked the players to concentrate on the general “feel” and “flow” of the score. The phrase-by-phrase quality of the performance allowed me to classify the materials into groups with different sound combinations and characteristics more efficiently. This particular organisation of the materials in the score was intentional since I already knew that I would have to process and transform them further in the studio.

It's important to mention that what would happen to the recorded materials during the post-production phase in the studio (although not clearly specified at that point) had already affected the way I organised the score or how I interacted with the musicians (through “conducting”) during the recording session. This is what Marcel Cobussen points out when mentioning the huge impact the producer and the creative use of the studio had on all the phases of making Bitches Brew; even on how players improvised during the recording sessions:

The fact that Miles and Macero already anticipated on the importance of the postproduction also had a direct effect on the way the musicians were “allowed” to interact. In other words, Macero’s role was not restricted to the postproduction process alone, but already predetermined the music made during the recording sessions (Cobussen, 2017: 144).

Something analogous can be traced in the field of rock music as well. For example, during the recording sessions of Lumpy Gravy Frank Zappa asked the orchestra to record parts backwards, so that when these passages are played back reversed, would contain an “aural” sonic effect. By listening carefully to the excerpts of “Part 1” from Lumpy Gravy I(right), this method of overdubbed reversed playback is audible (Borders 2001:134).

The connection of the starting material (in my case all the multitrack recordings of the score performance) with their ought-to-become transformed self was the point of departure for realising my compositions and something I was interested in exploring. The final compositions consisted of a mixture of (slightly and heavily) processed material derived from the recorded performances, as well as electronic sounds which are sonically and structurally informed by those same recordings through the use of voltage-control techniques [1]. Most of the sounds were manipulated and transformed using analogue studio techniques, methods and workflows exclusively, while others through granulation and other digital effects.

3. plod I & II

As explained earlier, due to the collage-like character of the recorded materials, I was able to classify them in several groups of sounds, depending on their timbre, rhythm and dynamics. Both parts of “plod”, which is the first two-part composition I decided to work on, are characterised by an interpolation between two processes with different structural and sonic elements.

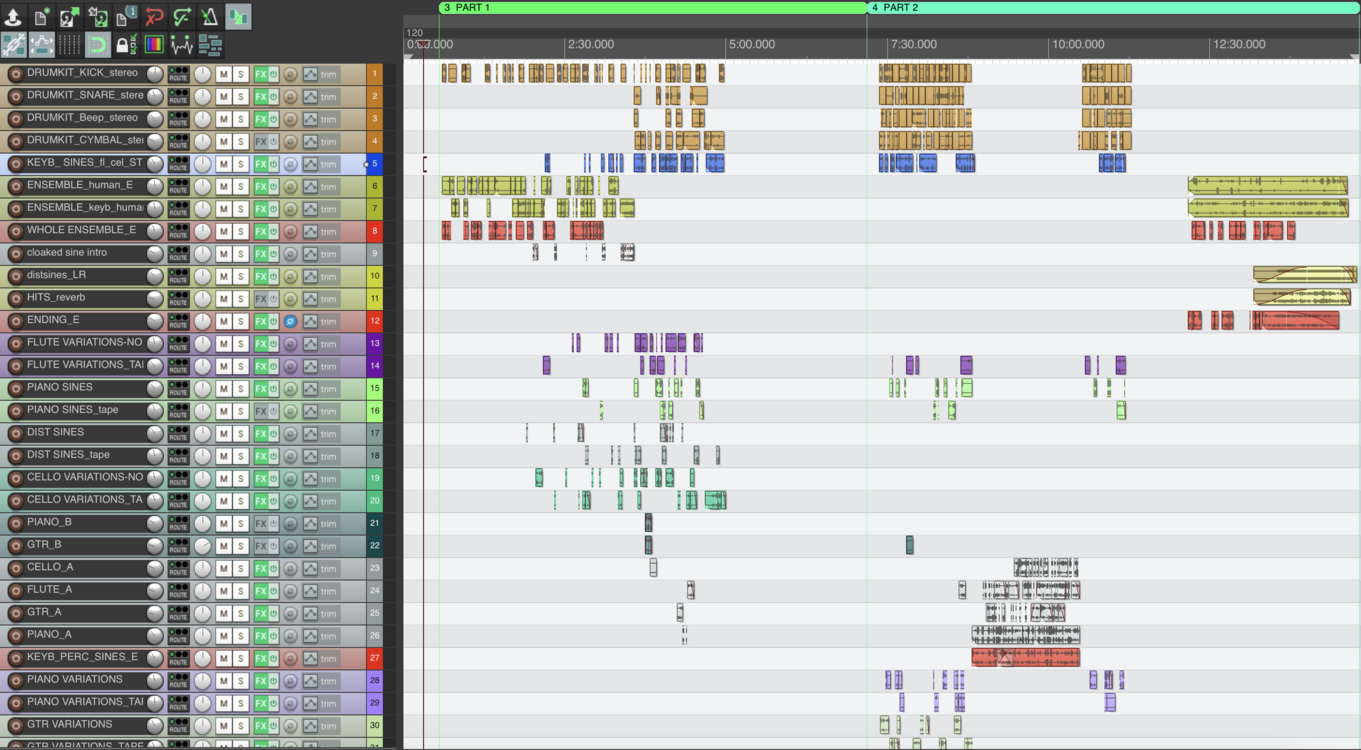

In “plod I”, the first process consists of a group of sharp percussive sounds, each one being a result of extreme time compression [2] of spontaneously chosen longer sound files. These sounds are also fed through a patch [3] (made using analogue modules in the Institute of Sonology’s voltage-control studio) which randomly repeats small fragments of them – creating “shadows” of the same material. As can be seen in Figure 3 (right), these two sound groups are highlighted with red and grey colour.

Opposing the first process, the second structure is a mashup of “chopped-up” instrumental recordings (light green tracks), generated by a voltage-control patch which “reacts” to the amplitude and frequency values of isolated instrument tracks. Each “chopped instrument” underwent a second generation of transformation which was superimposed on the first one (dark green tracks). This time, I chose to feed them through a tape machine and “perform” on it to alter their pitch and envelope contour - adding expression and density. Towards the end, a third group of slightly different sounds appears and functions as a transition to the second part of the composition, “plod II”. This group consists of several stretched material; again, spontaneously chosen from the group of percussive sounds heard in the beginning of the piece (red tracks), and a long upward glissando (almost 3 minutes) achieved by gradually increasing the playback speed of a sound with a steady tonal character (brown tracks).

“plod II” is organised in a similar manner. Two processes with different characteristics switch places or collide spontaneously throughout. One of these is made of “shuffled” fragments of sustained sounds varying in duration and their pitch-shifted (one octave higher and one lower) counterparts (see tracks 13 to 27 in Figure 4). These sounds are derived from playing mode “C” (players are asked to improvise between c and d#); thus, every fragment retains its tonality around “c-minor” but continuously varies its timbre. The other process consists of collages of instrumental sounds (see tracks 28 to 35), with mostly percussive and noisy sonic character. These were made using combinations of analogue and digital patches [4] which were “performed” by myself, so that parameters like fragment duration and density, envelope shape, panning, reverberation, and others could be shaped in real time.

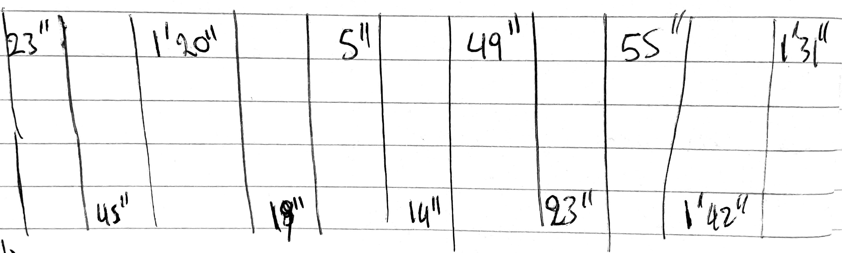

The sound materials were assembled as intuitively as possible and the durational proportions of the compositions evolved spontaneously and reflectively while listening to the emerging sound groups and structures. “plod I” was divided in two large sections where at around 4’30’’ the interplay between two structures becomes gradually more blurry and unstable. On the other hand, in “plod II”, as can be seen in the graph below depicting the approximate duration of each process, the rate of change between the two processes generally increases roughly towards the one third of the piece and then decreases until the end. Both pieces, although they can function as separate entities, create a bigger composition which loosely echoes the general “feel” of the score: an interplay between a collage-like sonic environment filled with a variety of articulations and a number of “focus points” with a steadier sonic character, represented by the playing modes where the musicians concentrate on a particular technique or sound.

Being fascinated by the output I designed a patch to create my own “device” for generating similar sounding results. Akin to the function of the custom device Zappa used, my patch did not generate any sound, but a process where each amplitude of the incoming signals is shaped by a separate randomly triggered envelope, resulting in a collage-like output. The sound materials of the collages were solely dependent on the input signals fed into the patch. Moreover, what made it “feel” like an instrument was the fact that some parameters like the shape of the envelopes and the density in which they were triggered could be manually controlled. With this feature I could create dense or sparse collages where the duration of each sound fragment could be adjusted in real-time. This particular patch was extensively used in other past compositions of mine (“Tape Ornaments”, 2019) and was responsible for creating all the collage materials heard in both parts of “plod”.

Other creative procedures involved the use of the analogue tape machine. As mentioned earlier, sections of “plod I” (1:17-1:45 and 2:15-3:06) were created by recording materials with a particular behaviour (in my case collages of instrumental sounds) on a tape and then transforming these materials by fast-forwarding/rewinding or starting/stopping the tape machine at different speeds and recording the result on another track. This introduced a more complex gesture-like sonic vocabulary based on how I was manually interacting with the knobs and buttons of the tape machine.

My intention with this improvised approach was to experience by first hand the procedures followed by rock musicians in the studio. Tape machines were one of the principal tools responsible for enriching the sonic palette of rock music in the 1960s. This can be exemplified by the use of tape loops which are sped up or reversed in the Beatles track “Tomorrow Never Knows” (Revolver, 1966) as well as in Pink Floyd’s track “The Grand Vizier's Garden Party, Part II: Entertainment” (Ummagumma, 1969) where bits of tape containing percussion materials (snare drum, cymbal, wood block and tom rolls) are shuffled and/or interpolated by short “mutes” created by splicing short leader tape pieces at different points as Guedson and Margotin (2017) speculate.

4. cloaked I & II

Discussing the ontology of recorded work in his book Sonic Writing: Technologies of Material, Symbolic, and Signal Inscriptions, Magnusson (2019: 145-146) compares several opinions about how the ontology of the rock work can be defined. At first, he talks about Stephen Davis' (2001) statement that rock work is a work-for-studio-performance whereas the classical is a work-for-live-performance. Addressing a critique to this statement, he then points out Andrew Kania’s (2006: 404) view who argues that rock music is for both the studio and live performance, and can contain both “thin” sound structures like the “rock song” and “thick” ones like the “rock track”. The former are open to alterations in instrumentation, lyrics, melody and harmony and the latter are studio constructions consisting of layers of recorded instruments and all the processes of composing in the studio. In the case of more experimental manifestations of rock music (like the ones who I am exploring), we can argue that the “thick” sound structures play a more crucial role in shaping the music compared to the “thin” ones. The Beatles can again serve as a characteristic example. According to Paul McCartney, beginning with Revolver their aim was to “distort” everything:

[...] to change it from what it is, and see what it could be. To see the potential in it. To take a note and wreck the note and see what else there is in it, what a simple act of distorting it has caused...and superimpose on top, so you can't tell what it is anymore (Ryan & Kehew, 2006: 422).

This thin/thick interaction and how a thin structure could become thick through studio experimentation was one of the main concepts of the second composition I set out to create. For the two parts of “cloaked” I wanted the structure and the sound materials used to be “dictated” by what the musicians chose to play during the third recorded take of the score. I was particularly interested in this take because of the variety of combinations of materials recorded, as a result of decisions made by the musicians and myself (as a conductor) in real time. According to Kania’s concept explained earlier, these performances would play the role of a “thin sound structure” (the “rock song”) which contain all the information (structural, harmonic, textural, rhythmical, behavioural) as translated from the score by the musicians.

The production process for “cloaked” was more systematic compared to the previous pieces. I began by writing down the path every musician took while performing the score, in order to create a “performance map” of the whole ensemble for take 3 (see figure below). As a result, I had an overview of the number and qualitative characteristics of the sound materials for each six-second bar of the score. This information would then be used as a “blueprint” for the construction of the two pieces. It was clear to me from the structure of take 3 that the two sections created by the points where the playing modes were cued (from the starting “E” to “D” at around 7’; and from this “D” to the ending “E”) would shape the two parts of “cloaked”.

Both examples mentioned above resonate with the procedure I followed to create the music for my album. The idea of creating something which would work as a demo to be put through a transformation process led me to compose an open score for four improvising musicians (flute, prepared piano, electric guitar, cello) which would function as the very first step of a compositional process rather than being part of the final stages of realising a musical result. The performance of the score would be recorded and subsequently the recorded materials would be used as a basis to create the studio compositions which make up the album.

The homonymous score was organised in such a way to create a framework for the musicians and conductor to “jam” (hence the title), by using a number of restrictions/rules which resulted in a “controllable” improvisation of spontaneously performed sonic events.

Yannis Patoukas

jammed

A case for exploring studio practices used in 1960s and 1970s experimental rock through the practice of electroacoustic music

1. Introduction

How can the study of studio practices used in experimental rock music of the 1960s and 1970s help inform electroacoustic music composition nowadays? How and why should we approach electroacoustic music composition from the perspective of rock production? Can the two sides be compared in terms of aesthetic approaches and production techniques? How can the notions of “studio improvisation” and “studio as instrument” be explored further?

My research project proposes to explore the different intersections between experimental rock music of the 1960s and 1970s and electroacoustic music, with regard to studio practices and production techniques, and their creative possibilities. The goal of the research will be to investigate the historical, technical and aesthetic context as well as the mutual feedback relationship between the exploration of those studio practices and my work as a composer.

In this essay I focus on some aspects of my compositional practice and the different ways they are connected to the research questions formulated in the beginning of this introduction, both in practical and theoretical terms. More specifically, I concentrate on the latest music project I realised; entitled “jammed” and self-released (both digitally and physically) as an album on 5 December 2022.

Two (fixed-media) pieces of the album are treated as “case studies” where I attempt to make clear how my compositional work is shaped so far in light of the research questions I intend to investigate. I look at the background of my decisions while composing, how I came to make this project the way I did and what kind of implications it has to the next steps of the research. Moreover, I analyse the compositional methods, workflows and technical processes I followed, in order to explore how they relate to the studio practices in both the field of experimental rock and electroacoustic music, and how they shaped the musical result I wanted to achieve.

2. Background

In recent years, it has become common to see releases concerning the ‘making of’ procedures of albums by (famous) experimental rock artists who were active in the early period of rock music during the mid-late 1960s. These releases take either the form of video documentaries or album compilations that contain alternative mixes, outtakes, or never-heard-before sound material. One recent example is the Beatles 2022 release of Revolver: Special Edition which casts a light on demos, rehearsal fragments and early-stage versions of tracks which eventually appear on the album Revolver (1966). Another example is the 3CD compilation album Meat Light (2016), which is part of a series of audio documentaries focused on the music of Frank Zappa and his band Mothers of Invention; and contains original mixes of the 1969 album Uncle Meat, several previously unreleased mix outtakes and track materials taken from the Zappa archives. What the two releases have in common is that they showcase how a ‘demo’ or initial idea becomes the final track or composition; by revealing particular steps of the transformation process. In the case of the Beatles, we can experience how the track “Rain” sounds in its original speed compared to the slowed down final version which made it to the album. Similarly, in Meat Light we can hear how the isolated guitar track of “Nine Types of Industrial Pollution” was actually recorded before being sped up and used in the final version of the piece.

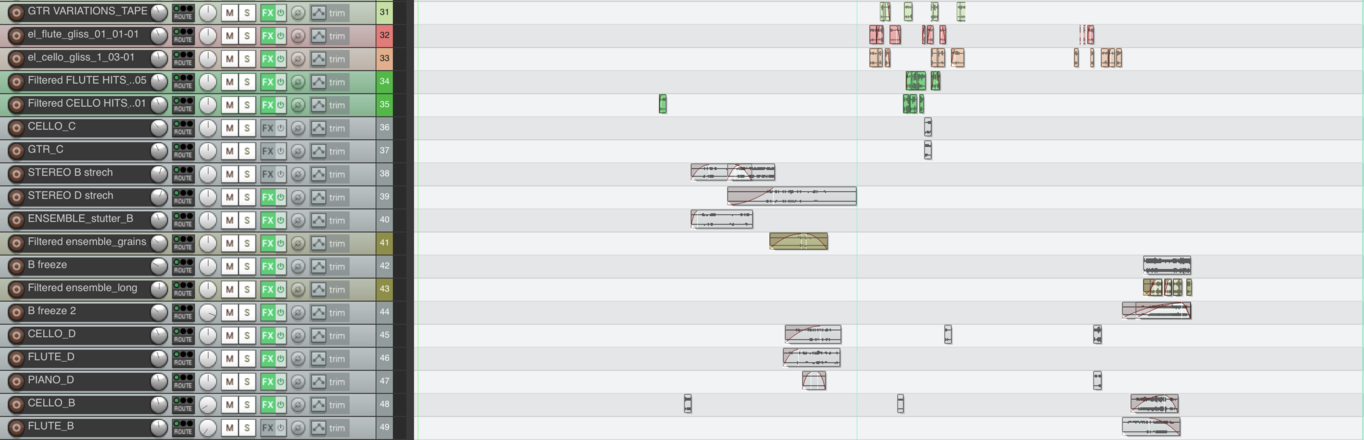

One of the first ideas that came to mind was to create a layer of percussive sounds, to work as an “anchor” structure between the modes, playing the role of an “electronic drum-kit” (see tracks 1-5 in Figure 5), into which at a later stage reworked and processed material deriving from the isolated instrument recordings would be woven. With this decision I was somehow vaguely following how a typical rock track is built on top of a rhythmic section, usually represented by the drums or different percussion. The “drumkit” sounds were generated by filtering pulse and noise signals using a variety of voltage-control patches.

In addition, their temporal organisation was roughly dependent on the number of sounds each instrument played according to the score. “Kick” sounds were based on the number of sounds played by the flute; “snare” on the piano; “hi-hat” on the electric guitar and “cymbal” on the cello. If we compare the zoomed-in and rearranged section of the Reaper session with the path of take 3 (see Figure 6), the density of the interpreted instrumental material roughly matches the density of the “drumkit”.

Listen from 0:10 to 1:36

The next step was to follow the structure of take 3 and make my own interpretation of the materials performed by each instrument. So, for every sound in each bar, I created an electronic equivalent, either by transforming the corresponding instrumental sound (see tracks 6, 8, 11-14, 19-26, 28-49 in Figure 5) or by replacing it completely with a synthetic one (see tracks 7, 9-10, 15-18, 27 in Figure 5). During this procedure, I was sometimes faithful to the written numbers/letters/articulations and sometimes acting completely intuitively if I felt that the music demanded it.

For the interpretation of the playing modes, I used a granulation Max patch to shape the sound or behaviour I wanted to achieve for each case. Thus, to interpret a long sound (playing mode B) I created a “freezing” effect by randomly sampling and playing a big number of short grains selected from a particular section of a sound. Different presets of this Max patch were also used to interpret the rest of the modes.

The other groups of materials were transformed using analogue techniques such as:

● varying (once or constantly) the playback speed of a sound by using a tape machine

● collage-making using the same patch as in “plod”

● voltage-controlled ring modulation (where the modulation is affected by the amplitude of the sound source being ring-modulated)

● voltage-controlled filtering (where the cut-off frequency and resonance are modulated by the frequency and amplitude characteristics of the sound source being filtered)

and in some cases, combinations of the above.

In Kania’s words, these interpretations of the materials and how they would be layered, edited, mixed and transformed in the studio, would be the “thick sound structures” (the “rock track”). However, in my case these thick structures do not manifest thin “songs” as Kania puts it, but most importantly themselves (!); bringing the creative studio procedures in the foreground of the composition. In other words, what was important for me in this composition was not to present a documented performance of the score materials but the different generations of transformations of these materials as a result of several “studio performances”. With the term “studio performances” I am referring to all these actions which take place during the production phase of a studio composition and contribute to the construction of the sonic elements which make up a piece of music. One example could be the track “The Chrome Plated Megaphone of Destiny” from the Mothers of Invention’s album We’re Only In It for The Money (1968), where the focus of the music is on how the sounds are changed through studio experimentation and using it as a compositional tool.

5. Conclusion

Nowadays electroacoustic music composition works more as an umbrella term which includes a diverse range of practices: studio composition, computer programming, analogue and digital signal processing, algorithmic composition, live electronics, improvisation, sound art, field recording, composing by using the spatial aspects of sound and all possible combinations of the above. At the same time, we are experiencing an increased interest among creative musicians to exploring and rediscovering early-stage studio production techniques, workflows and ways of using older (analogue) electronic devices for music-making.

Therefore, I believe that studying the studio practices and production techniques of 60s to mid 70s experimental rock can offer a fresh perspective on this field. For example by taking advantage of the creative possibilities of analogue equipment, techniques and workflow, referring to their usage in rock music, as a source of musical orientation difficult to find in the limitless possibilities offered by computer-based composition. Various technical aspects of music-making in the 1960s entailed what might be considered “technical limitations” by today’s standards, but I see these as opportunities to seek creative solutions which serve the music I am interested in making.

Each part of the case studies in this essay can be expanded and investigated in more detail and depth both in theoretical and practical terms. This can be done by exploring the creative possibilities of a wider variety of studio techniques and their application to compositional ideas. We also saw how the notions of “studio improvisation” and “studio as instrument” can be approached as a compositional method; something which is worth delving deeper. In both rock and electroacoustic music, spontaneity has often been incorporated into composition, creating a connecting thread between rock music and free improvisation, a path which can be explored by creating improvisational scenarios (open scores, recording setups, etc). These scenarios could be informed by the study of improvisatory elements found in the intersections between experimental rock and electroacoustic music.

Working with analogue equipment to design techniques or compositional ideas, which could anyway be done easier and faster using digital tools, gave a sense of musical variation to my music not possible to be achieved by other means. In my case, musical variation equals to sound variation. An analogue audio signal flow is made out of a variety of stages including a number of different interconnected physical devices or tools which don’t leave the sound unaffected. For example, a sound which is recorded and played back on a tape machine and then amplitude-modulated by an analogue low frequency oscillator (LFO) module will eventually feature more signal noise and/or other unique frequency alterations as opposed to doing something similar in the digital domain. As Melle Jan Kromhout (2021: 104) argues in The Logic of Filtering

[…] the sound that comes out of the speakers at the end of the chain is shaped as much by the specific conditions at the moment that the “original” first sounded, as by all of the filtering channels that subsequently shaped its sonic contours along the way. It is impossible to determine where the one’s influence ends and the other’s begins.

These irregularities printed in the sound, regardless of their subtlety or crudity, are not treated as something I need to remove from my music in order to increase the level of “fidelity”. Instead, they are embraced as musical and sonic materials or modulation signals ready to be used creatively for music making and thus contributing to an aesthetically and sonically varied output.

In addition, my processes of manipulating sound were heavily influenced by the tools and studio techniques I used, as well as the conditions in which I put myself to compose. Having to physically move inside the studio space from one device to the other and spending more time to interact with tools, creates a slower and non-linear way of working. If we approach this more abstractly, when you enter the premises of a studio, you physically exist in the “insides” of an instrument, affecting on how it’s different parts operate and function. Thus, every compositional idea, device combination, or sound transformation technique could not be exactly (intentionally or unintentionally) duplicated, resulting in extremely diverse musical results.

All the different steps I followed to create these compositions contained several degrees of spontaneity and systematicity which I find extremely interesting to continue exploring, documenting, expanding and creatively applying through the studio practices mentioned in this essay. I look forward to doing this through artistic research, where my findings are not intended to “restore” the music in question but to act as a starting point for new music of my own.

References

Borders, J. (2001). Form and the Concept Album: Aspects of Modernism in Frank Zappa's Early Releases. Perspectives of New Music, 39(1), 118-160.

Cobussen, M. (2017). The Field of Musical Improvisation. Leiden University Press

Davies, S. (2001). Musical Works and Performances: A Philosophical Exploration. NY: Oxford University Press.

Everett, W. (1999). The Beatles as musicians: Revolver through the Anthology. New York: Oxford University Press.

Guesdon, J., Margotin, P., Elliott, R. G., & Smith, J. (2017). Pink Floyd: All the songs: The story behind every track. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal.

Kania, A. (2006). Making Tracks: The Ontology of Rock Music. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 64(4), 401-414.

Kromhout, M. J. (2021). The Logic of Filtering: How Noise Shapes the Sound of Recorded Music (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190070137.001.0001

Magnusson, T. (2019). Sonic Writing: Technologies of Material, Symbolic, and Signal Inscriptions. USA: Bloomsbury Academic. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ryan, K. L., & Kehew, B. (2009). Recording the Beatles: The studio equipment and techniques used to create their classic albums. Houston, TX: Curvebender Publishing.

[1] The principles of voltage control were developed in the early 1960s by Don Buchla and Bob Moog, working independently. Their work was in turn based on some circuits designed for the RCA Synthesizer in the 1950s, and the work of Lamonte Young in the 1940s. Voltage control was a major step forward; prior to that time, synth parameters were usually controllable only manually by knobs or switches, which severely limited the playability and expressiveness of the instrument.

See

https://electronicmusic.fandom.com/wiki/Control_voltage

(accessed 1/2/2023).

[2] A time stretch effect in which the duration of a sound is decreased but without altering its pitch.

See https://electronicmusic.fandom.com/wiki/Time_stretch (accessed 1/2/2023).

[3] A set of parameter settings, signal routings, and possibly patch cord configurations that produces a particular sound on a synthesiser. The word "patch" stems from the fact that the first mass-produced synthesisers were modular synthesisers, and on these sounds were formed by using patch cords to route signals from one module to another.

See https://electronicmusic.fandom.com/wiki/Patch?so=search

(accessed 1/2/2023).

[5] This information derives from a personal communication with John Kilgore who worked as an apprentice at Apostolic Studios in NYC between 1967 and 1969. There, he observed Frank Zappa as he made the albums We're Only In It For The Money, Lumpy Gravy, Uncle Meat and Cruising with Ruben & the Jets. Retrieved from: https://www.johnkilgore.com/about-1 (accessed on April 29, 2019).