Ben Spatz develops an “epistemology of practice” in his inspiring volume What a Body Can Do: Technique as Knowledge, Practice as Research. Spatz makes a distinction between technique and practice, defining technique as knowledge, structuring “our actions and practices by offering a range of relatively reliable pathways through any given situation” (Spatz 2015, 26). Practice, on the other hand, in Spatz’s thinking refers only to “concrete examples of actions, moments of doing, historical instances of materialized activity” (op. cit. 41). So in Spatz’s vocabulary, technique is repeated in variations to enable an accumulation of practice-based knowledge.

Why is audience membership not a practice?

When I started to work with the concept of the audience, I struggled with the issue of a research practice. I had made an observation that audience membership in performances is different from making them in terms of practice, in two ways.

Practice is an integral and explicit part of making artistic performances, and it consists for the most part of preparation for public performances. In the local context of institutional theatre in Finland, it is a standard structure to have 40 rehearsals; rehearsals are appointments, in which the working group gathers to practice the upcoming performance. In addition actors normally practice on their own. In the fine arts-based genre of performance art, practice of this kind is not a standard, but artists usually consider they have a practice, which in general means their individual and idiosyncratic way of preparing and executing performances, a way they develop their skill through repetition. Also those performing artists, whose performance practice is improvisatory, use a lot of time practicing the abilities they need for that. All of these aspects of practice function as development of skills, accumulation of bodily knowledge and preparation for public performances.

Like practices of making, also audience membership is repeated with variations, accumulating bodily knowledge and receptive skills. However, there is also a difference in register present. Audience members’ conscious effort to develop skills and the preparation they engage in before attending an event are minimal. Skills do develop. This can be perceived for example in feelings of comfort and discomfort audience members experience in performances, especially if they contain a participatory aspect. If one attends participatory performances frequently, they are likely to be more at ease with them than someone who has never attended one before (see as an example the audience responses in Draft 7). But even those who attend participatory performances frequently, like myself, do not really aim to develop their skills, at least nobody talks about it. Juha Varto writes: “for the practitioner, understanding involves skill; for the recipient, interest” (Varto, 2018, 78). Moreover, their preparation for events of audiencing is remarkably scarce. One makes a choice to attend, books a ticket, arranges time on that date, arrives at the site. Nothing even remotely comparable to the 40 four-hour rehearsals the actors engage in.

Secondly, as Spatz articulates, practice is active, composed of moments of doing, which also links it to making performances. This can be illuminated by an etymological perspective. The etymology of practice suggests that it is “active”, “effective”, “fit for business” and leads to “accomplishing”, “succeeding” or “coming to an end”. Acting, as well as agency, originates from "doing, driving, setting in motion". Performing in turn denotes “doing, carrying into effect, finishing, accomplishing” while doing comes from “making, acting, performing, placing”. One could say these terms form a family of meaning: to practice, to act, to perform and to do, as well as the related nouns a practice, an act, an action, a performance and agency, refer to similar phenomena. The makers of art are engaged in performing and acting. Performances are practiced or they are based on a practice. Both practices and performances are in the realm of doing and they express the agency of the makers of art. (Online Etymology Dictionary, accessed 21.1.2025)

Audience membership in contrast includes by default a deferral of action. Without exception, all performances I can remember having attended have started with a transfer of agency from me, the audience member, to the makers or performers of the work. In more experimental works, this relation can develop into a complex dynamic overlap of agencies, a significant number of them also distributed to me. But even then the primary agent is the maker. The research practice at hand is an example of this kind of dynamic: in my experiments, I make a gesture of retreating from the center of attention and hand plenty of agency over to audience members. Regardless of that, my preparatory work renders me as the authority of the performative event.

The audience reserves their agency to grant their attention and a limited space-time of activity and performance to the makers. The implicit order of things is that the performers (as etymology suggests) do things and the audience (as etymology suggests) perceive the things done by the performers.

A bipolar system

This asymmetric relation can be visualized as a magnetic system, where two poles exist in opposite ends of the same axis. This polarity is familiar from professional and theoretical discourses of performing arts, especially if the themes of audience or participation are addressed (Fischer-Lichte 2008 and Rancière 2009 are good examples of theorization based on a bipolar substructure). Performance versus its reception, activity versus passivity, the stage versus the auditorium.

As if to support these discourses, live performances typically materialize this polarity. The active performers who set things in motion, carry into effect, act and do, are faced with those who receive, spectate, listen and reserve their agency for the purposes of the performance. Namely, the performers encounter their audience. This polarity is noticable from the earliest documented forms of performing arts to the present day, in all kinds of variations. An asymmetric relation between those who perform and those who are in the audience is constant: the performers prepare themselves for the performance and initiate the event by placing themselves and/or the results of their actions before their audience. The audience in turn prepare themselves only minimally compared to the performers and become attentive when the performance is initiated.

While contemplating these points, I started to hesitate using the word practice to denote events of audience membership. My question was: if artists have a practice, what do audiences have? To be a member of an audience is arguably something that is done with the body: an audience member enters the site of the event, situates their body in the space in relation to other bodies, takes positions, moves, uses all their senses and is affected in multiple ways, for example. Also, a member of an audience is not devoid of agency: there is a complex negotiation of power and responsibility taking place in any performance, be it that in most cases it is rendered invisible by the conventions surrounding it. Audience members have the option to interrupt the performance if they do not accept what is taking place—ethical responsibility is included in attendance. Thirdly, most audience members become audience members repeatedly, attaining “practice-based knowledge” and accumulating expertise in how to be in the audience of those genres of art which they repeatedly attend.

It seems clear that audiencing has practice-like properties—it is not a non-practice. However, it is also significantly different from an artistic practice, as I have analyzed above. The polar and asymmetrical relation between performing and audience membership suggests that the essential function of an audience is not doing something, performing, acting or practicing. That said, it is not a complete opposite of those attributes either, rather the doing, performing, acting or practicing into which the audience takes part is another kind of practice. My proposal of a term for this other kind is parapractice.

Parapractice as a term

The term parapractice is inspired by the terms 1) paratheatre, used by the Polish theatre director Jerzy Grotowski to address his experimental work in 1970s that abandoned some of the basic elements of theatre, such as the division between performers and audience, and 2) para-social, introduced in the context of psychiatry by Donald Horton and R. Richard Wohl (Horton et al. 1956) and referring to one-sided relationships and interactions between a media user and media persona. The pre-fixe para derives from beside, as in parallel: beside one another; two lines that lie on the same plane but never meet (Online Etymological Dictionary 2 November 2023). Paratheatre would then be something that takes place on the same plane as theatre, but never actually becomes theatre; para-social relations would take place beside social interactions but would never acquire their reciprocity.

Grotowski’s work, while utilizing performer techniques developed in the realm of theatre, aimed at transcending theatre, renouncing the one-sided or asymmetric relation between an actor and a spectator to enable direct face-to-face meetings. This adventure envisioned a form of art without “the division into the one who watches and the one who acts, man and his product, the recipient and the creator”. (Schechner 1997, 208-11.)

This “sentimental project” (Schechner 1997, 209) is akin to Allan Kaprow's aim to “eliminate the audience” by developing Happenings (Kaprow 2006, 102-4), with the genre difference of the obliterated audience: Grotowski experimented with a theatre without audiences, Kaprow with a fine arts -based performance without audiences. In both cases the idea was that the audience would be wiped out as a function. People, who do not belong to the group who make a specific work, are still invited to attend. However, these people are ideally stripped of any exteriority in relation to the work or any functional opposition with the makers. They acquire other functions, such that of ritual participants. The aim of Grotowski and Kaprow would then be to bring their audiences to the realm of practice.

With no straight experience of Grotowski’s and Kaprow’s works, it is hard to tell whether their work took place before audiences or as a ritual communities. Either way, the concept of paratheatre is valuable for the purposes of my research. It proposes a realm of art, which commits to some of the fundamental aspects of theatre and rejects some of them. It pays respect to the genre by adapting and re-adjusting its name. In this way I propose that audience membership is a parapractice. It takes place on the same sphere of phenomena as practice, but it will never acquire the prioritisation of action inherent in a practice.

The parapractical nature of audience membership can be further elaborated with the help of philosopher Antti Salminen, who describes prefix para- as a parasitical linguistic element, which lives of other words and twists their meaning but rarely turns them into their own antithesis. “It is not a negation and therefore its dialectic is residual, unpredictable and asymmetric”. Paralanguage belongs to the materiality of language, “anticipating, excessing, deceiving and implying”. (Salminen 2015, 119; my translation) Audiences embody the residual and excessive dimensions of performances, the unarticulated and unexpressed traces of staged actions, the silent resonances which are not discharged as performed agencies but merely as involuntary sounds, restless movements and micro gestures implying something ambiguous.

Paratechnique

How does one then parapractice? For an artist like myself parapractice easily becomes productive and practicesque—I often start to analyse my own experience and use it for the purposes of developing my thinking. A parapractice in a purer form would be much less useful. A suitable metaphor is the realm of dreams. Following the thought that was induced in me by Jenni-Elina von Bagh’s A Prologue (referred to in Chapter 2.1), an audience member has to be awake and dreaming at the same time. Audience membership can be described as a parallel condition to that of dreaming: the body yields to a relatively passive state while consciousness travels in a contingent, but resonant way. The more active the role of the audience body becomes, the less room there is for this subconscious level of the art event. Paratechnically, the parapractice of audience membership has to do with skills of surrendering oneself, in the company of others, to dreams triggered by performances, while staying awake. Paratechnique has thus a paradoxical quality, familiar also from spiritual meditative practices, in which techniques are intentionally used in order to strip the practitioner of intentionality. To parapractice is to balance between a conscious intention and its absence. In the frame of my study, paratechniques of audience membership are particularly connected with the resonant quality of audience bodies and the inherent dynamics of consonance and dissonance, fluctuating in complex patterns constantly within an audience body. The development of these paratechniques would be a subject for further study.

Making audiencing a practice

Could there be a way to liberate audiences from their subordinate position? Could audience membership acquire the status of a verb and could audiencing in fact be a practice contrary to what I have argued above?

In 2011 I took part in developing a workshop with the title Spectator Education. It was organized by the Reality Research Center and taught by artists Pekko Koskinen, Risto Santavuori, Pilvi Porkola and myself. We devised a five-day dramaturgy of exercises and discussions, aimed at equipping the participants with techniques of audiencing. We had noticed that while artists go through an education of several years to learn how to make works, spectators have almost no educational possibilites of any kind to develop their spectatorial abilities, except for occasional outreach events organized by theatres and other institutions. We found the idea of educating spectators to be funny, even absurd in the prevalent cultural paradigm of the time.1 Now I would argue that this was because the context of art does not support practices of audiencing as such but is based on a supposition that audience bodies are subordinated to performances. The workshop and its motivations anticipated the concept of parapractice proposed here.

In and around the Reality Research Center of the early millennium there were also other experiments, which prototyped practices of audiencing in the guise of art and gently questioned the hegemonic maker-audience-polarity. In the Gateless Gate, created by Eero-Tapio Vuori and Jukka Aaltonen and staged originally in 1999, the performer guides audience members to a gateway of a residential building and provides chairs for them to sit on. Then they sit and look through the gate into the street for an appropriate duration, usually between 45-55 minutes. The events taking place on the street become the performance through this framing. While the Gateless Gate is instigated by its makers, within it audiencing can be prototyped as a practice, since the performative events that take place become performative events only through the existence of the recipients. (Gateless gate August 2021, see also The Wall 2011)

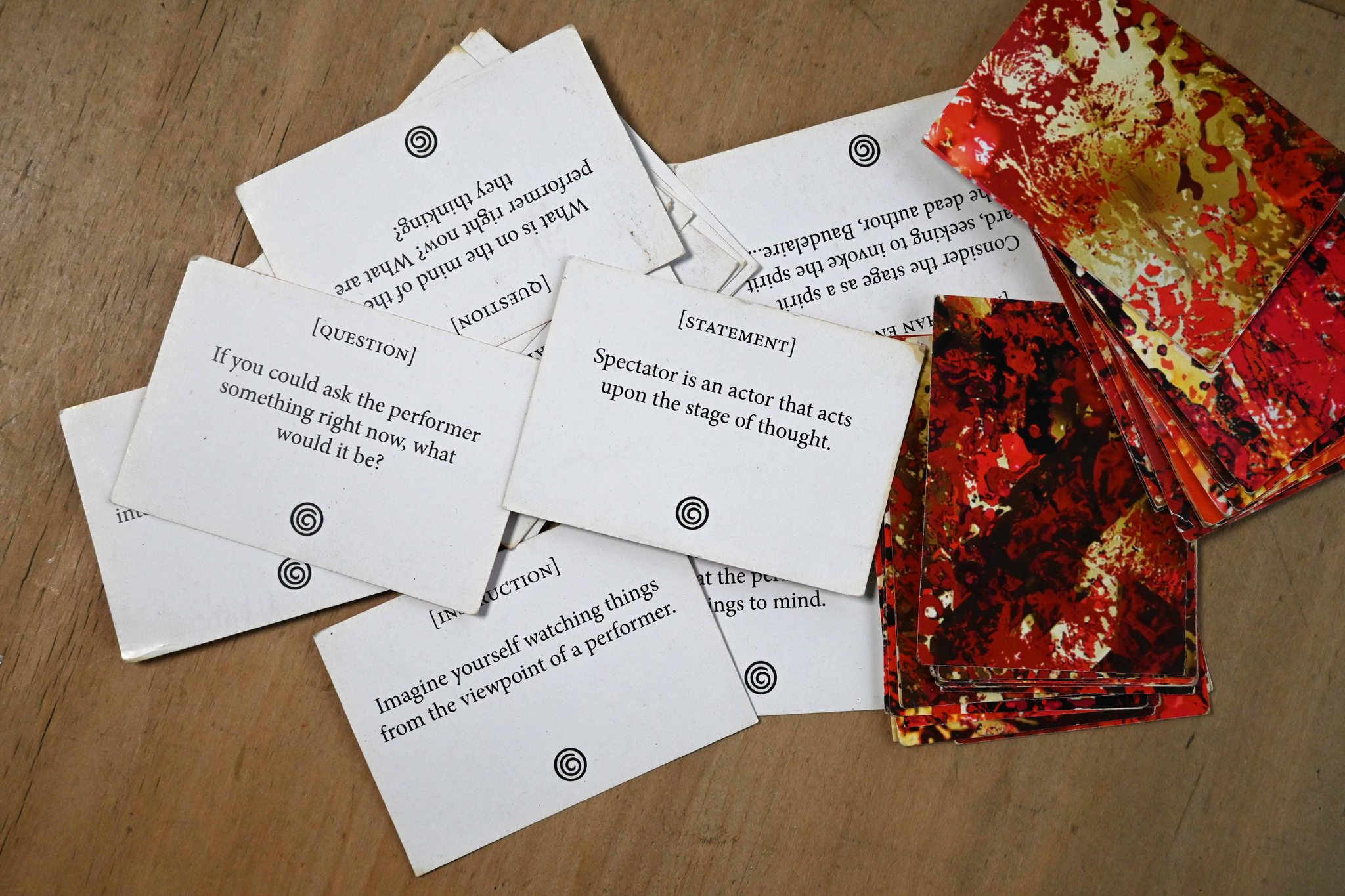

Pekko Koskinen and his collaborators appropriated several phenomena by framing them as performances under the title Staged Larceny: they “stole” a performance by another artist, the public figure of the populist politician Timo Soini and the televised Independence Day Celebration at the presidential palace2. For example, the audience members of Staged Larceny arrived at the venue where Doris Ulich’s work more than enough was performed. They were handed a deck of cards, each of which provided a different kind of spectatorial orientation with which to approach the appropriated performance. One of the makers of Staged Larceny, game designer Gabriel Widing, described the actively distanced perspective on audience membership that participants of Staged Larceny would utilize:

We will be entering the territory of this performance disguised as typical “spectators”. Now, what is a spectator? Spectator is a observatory being that operates near performances, staying mostly still and silent, thus making itself less noticeable—a spectral ghost, of a sort. From this, nearly invisible position, they observe and consume things such as performances. They also serve as cultural shields against the eruptions of performances—a buffer between the rawness of performance, and the regularity of everyday life. (Widing 2011)

Koskinen’s and Widing’s approach was a way of reversing the subordinate relation of the audience and the performance as well as prototyping a way any cultural phenomenon could be approached via active audiencing. (Staged Larceny November 2011)

As a third example, the experiment devised by Anniina Väisänen in her BA thesis (and applied by me in Draft 21) framed a pre-scheduled 5-minute period of her life, once a day for a duration of 30 successive days, as an esitys/beforemance. Each day of January 2013 when her alarm went on she would take the position of an audience member in relation to her environment and let go of this position five minutes later when the alarm would ring again. (Väisänen 2013)

The Gateless Gate, Staged Larceny and Väisänen’s experiment Tosi esitys (Eng. The Real/Actual/True Beforemance) gave their audiences tools with which they could gain audience agencies that could be repeated with relatively small effort independent of their authors. There have been also more extensive and influential endeavours to develop receptive practices. Composer and accordionist Pauline Oliveros was a pioneer through the development of techniques of deep listening (The Center for Deep Listening, accessed 16.11.2024). Building on Oliveros’s work, Tanja Tiekso suggests that listening is a skill independent from music; the purpose of music is to help us enter the state of listening (Tiekso 2024). Rajni Shah’s experiments on listening are closely related (Shah 2021a&b). What differentiates practices of insubordinate audiencing from theories that emphasize the recipient’s role in art (such as reader-response theory regarding the genre of literature (Castle 2013, 153-159) or Jacques Rancière’s Emancipated Spectator regarding theatre (Rancière 2009))—as well as from journalistic or curatorial practices taking place in audiences—is that the former do not need the initiative from a maker.

I consider that the propositions of insubordinate audiencing call for a reformulation or an expansion of the institution of art. If this kind of sensitivity would be supported and cultivated by our educational system and powers that be, the emancipated spectator could invite a state of audience resonance on their own initiative, experiencing the everyday from the perspective of a spectator—events would appear performative as a result. To acquire and maintain that kind of state, practicing would most probably be necessary. And for audiences to become emancipated, this practice would need to have a collective dimension and substrate. This kind of development would be akin to classic Avant-garde art practices with revolutionary aspirations: the annihilation of art through artistic means and subsequent breaking through to the other side: to reality, to life. This kind of interpretation would differentiate audiencing from Debordian spectatorship—whereas the spectatorial dynamic, as Teemu Paavolainen articulates, is based on “passivity and separation” (Paavolainen 2024, 122). Audiencing, as well as audience membership as it is presented in this study, is defined by complicity and resonance.

My proposal is that audience membership is procedurally secondary within the current context of art, but experimental artistic practices can challenge definitions of art and propose emancipatory perspectives for those engaged with it. By developing a practice of audiencing, the submissive position inherent to the definition of an audience can be dismantled. This research project does not extend further to this direction—I do not develop or document the techniques of audiencing, although that would be an interesting project in itself. My focus is on audience membership as a parapractice, as something that is not by default based on a conscious effort to develop anything. I aim at disclosing the parapractice taking place in audience bodies and thus making us more aware of the resonant potentialities we habitually stay unaware of.

1 Since then, for example Baltic Circle International Theatre Festival and Moving in November Festival have arranged workshops and structures in which the audience membership of their program is facilitated and surrounded by collective discussions. New Performance Turku Biennale has a program of curating and training “audience embassadors”, local people from different demographical groups, who invite and assist new audiences for the biennale. Also different Helsinki-based institutions have recently prepared instructions for their audiences, for example Zodiak Center for New Dance, Totem Theatre as well as art museums Emma and Amos Rex.

2 I collaborated with Koskinen in the operation which framed the Independence Day Reception as a performance by Reality Research Center.