Table of contents :

Introduction

-

Background

-

Research Purpose

-

Research Questions

-

Research Methodology

Chapter I : Light as a Compositional Tool

- The Evolution of Light

- Sound-Light Interaction - Scriabin’s Vision of Total Art

- Can Light be an Instrument?

- Interdisciplinary Art Forms with Light

Chapter II : The Reciprocal Transformation of Sound and Light

1. Bidirectional sound-light interaction

- Light Responsive Systems (Sound-to-Light Interaction)

- Sound Responsive Systems (Light-to-Sound Interaction)

- Simultaneous Sound-Light Systems

2. Light Devices and Sources in my Composition

- Photovoltaics: Solar Panels as Microphones

- Amplifying Light: Using Contact Microphones to Articulate Light

- Oscillators and Photoresistors as Light-Sensitive Devices

- The work of Viola Yip: Blurring the Boundaries of Sound, Light, and Movement

Chapter III: Applications in my Music Practice

- Belling in Sunrise, Drumming in Twilight (2022)

- Shadows in Three (2023)

- Stages (2024)

Chapter IV: Conclusion: Expanding the Horizons of Light and Sound Integration

Bibliography

Introduction

Background

Light has always evoked strong emotional responses in me, with different intensities, colors, and movements shaping my creative vision. This connection is rooted in experiences from my childhood, especially with my father, who, as a journalist, always brought his camera to family events, instinctively searching for the best light to capture each moment. This emphasis on “finding the good light” sparked my appreciation for how lighting can frame an experience.

Living in different environments has further shaped my fascination with light. The lighting in Taiwan, with its bright, white intensity, creates an environment that feels energizing and vibrant, often inspiring me to stay productive even late into the night. This constant glow of the city adds a dynamic pulse to the surroundings, shaping a lively atmosphere that always feels alive. By contrast, the Netherlands offers a more subdued, warm lighting atmosphere, encouraging a different rhythm in my work, one that invites reflection and a deeper focus on the natural world around me. Living between Taiwan and the Netherlands, I noticed how light plays a distinct role in how I see and connect with my surroundings. Experiencing these two distinct lighting cultures has enhanced my appreciation for how light shapes our environments, emotions, and interactions, fueling my desire to create immersive, more-than-auditory experiences that blend sound and visual dimensions in my work.

The quality of natural light in the Netherlands has long been a significant factor in the work of painters such as Johannes Vermeer. His paintings often capture a unique relationship between light and space, emphasizing how light can reveal textures, create atmosphere, and evoke emotion. Art historian Svetlana Alpers discusses how Vermeer’s use of natural light was integral to his artistic vision, as he carefully observed how daylight interacted with interior spaces to shape his compositions.1 The way Vermeer allowed light to guide the viewer's attention is something that resonates with my work, particularly in the exploration of light as a compositional element.

These reflections on light remind me that light is not just an external phenomenon, but an active force that shapes our experiences, perceptions, and creative processes. Just as Vermeer’s paintings cannot be separated from their careful use of light, my own compositions seek to merge sound and light as equally vital components, creating performances that invite audiences to both hear light and see sound. A pivotal moment in my artistic journey occurred during the Gaudeamus Festival 2021, where Igor C. Silva's piece "Follow," performed by Stephanie Pan and Ensemble Klang, captivated me. The performance featured lights projected onto the stage backdrop and floor, requiring Pan to precisely memorize her movements to align with the beams of light. The dynamic interplay of light and sound inspired me to explore integrating light into my own compositions. This inspiration was further solidified during a composition group lesson when a classmate's piece, intended to include light, was presented without it due to a technical issue. The absence of light left the performance feeling incomplete, highlighting how light can enhance the emotional depth and immersive quality of a musical experience. This realization deepened my understanding of the interplay between sound and light, driving my passion to create similarly impactful works.

Nowadays, many people are strongly influenced by visuals, and this perspective plays a big role in how I approach composition. This visual-dominant perspective, combined with my visually inspired approach to composition, drives me to make light a central compositional tool. By blending lighting with sound, I aim to create performances that resonate both sonically and visually, capturing attention and enhancing engagement through a compelling, bimodal experience.

Research Purpose

Through my experiences attending musical performances, I've always been captivated by the power of light design. There's something truly mesmerizing about how light can draw your attention, sometimes even overshadowing the music itself and becoming the star of the show. This fascination has led me to explore the idea of bringing light to the forefront of performances, treating it not just as an accessory, but as a core element of the composition.

I'm particularly intrigued by the idea of composing with light, where the music is influenced by visual elements, creating a more synchronized and immersive experience. Imagine how incredible it would be to perceive visual and audio elements together in perfect harmony! This approach could transform the way we experience performances, making them more dynamic and engaging.

Inspired by artists like Viola Yip and Hugo Morales Murguia, who integrate light, sound, and physicality in their work, I aim to investigate how light can become a fluid and responsive medium. By doing so, I hope to expand the boundaries of musical performance, positioning light as an integral compositional parameter. This research seeks to explore new possibilities for integrating visual and sonic elements, ultimately enhancing musical creativity and transforming the relationship between performance and space.

Research Question:

How can light be redefined as an active compositional element in live music performance, dynamically interacting with sound to shape the performative environment and enhance the physicality of both the performer and audience experience?

Research Methodology

This research employs a practice-based approach to explore the role of light as a compositional element in contemporary music. As a composer, my methodology focuses on hands-on experimentation with technologies like photoresistors, Digital Multiplexing (DMX) lighting, and analog oscillators, guided by self-learning and input from artists like Hugo Morales Murguía.

The methodology includes:

Artistic Experimentation and Composition Development:

-

Integrating light as an active musical parameter to influence form, performer interaction, and audience perception.

-

Developing real-time interactions between DMX lighting and musicians.

Exploring performer-controlled lighting systems and structured improvisation to test light-sound interactions.Case Studies and Artistic References:

-

Analyzing works by artists like Viola Yip, Hugo Morales Murguía, and Ryoji Ikeda to understand light’s role beyond traditional stage design.

-

Comparing approaches to bidirectional light-sound interaction to align with my artistic vision.

Technical Investigations and Material Studies:

-

Building and modifying light-sensitive instruments and programming DMX-controlled lighting for real-time performance.

-

Testing various light sources to examine how different intensities and angles affect sound.

Documentation and Reflection:

-

Recording performances, analyzing feedback, and adapting compositions based on practical insights and audience responses.

Chapter I : Light as a Compositional Tool

1. The Evolution of Light - From Fire to Semiconductors

Light has evolved from a simple, functional necessity to an integral element of artistic and technological innovation. Early light sources were primarily natural and organic, with fire as the dominant human-controlled means of illumination. For ancient cultures, fire was not only essential for survival but also played a central role in social and ceremonial activities. In many Indigenous tribes, fire was the heart of ritual gatherings and performances. For example, the Native American Plains tribes often incorporated fire into their Sun Dance ceremonies, which included singing, drumming, and dancing in circles around a central fire. Similarly, the African San people performed their Trance Dance around a fire, where the interplay of light and shadow heightened the spiritual and communal aspects of the ritual. These ancient connections between fire, movement, and light laid the foundation for the interplay of light and performance in later art forms.23

As societies advanced, light sources became more refined; oil lamps and candles improved in efficiency, allowing for greater manipulation of the living environment. This foundation of artificial light provided a basis for human activity after dark and contributed to early architectural and societal structures. These early forms of lighting, though rudimentary, facilitated activities ranging from communal gatherings to the development of artistic expression in the form of theater. For instance, in ancient Greek theater, stages were strategically built on hills to harness the full potential of the sun, which illuminated dramatic performances while keeping the light out of the audience's eyes. In contrast, Italian theaters began using candles in the late 1500s, with architects like Sebastiano Serlio discussing their use.4

The introduction of electric light marked a revolutionary shift in both daily life and artistic expression. The advent of electric lighting began with early innovations like Humphry Davy's electric arc lamp in 1800 and Thomas Edison's practical incandescent bulb in 1879, which brought a new level of control and reliability to illumination. This breakthrough not only extended the day into the night but also paved the way for the electrification of entire cities, transforming the urban landscape. Electric lighting allowed for greater manipulation of space, enabling artistic creators to explore new dimensions in theater and performance. By the 20th century, the emergence of fluorescent and later Light Emiting Diode technology further expanded lighting’s capabilities, offering brighter, more energy-efficient solutions. LEDs, in particular, introduced not only a more efficient and safer lighting option for large spaces but also provided artists with the ability to control light digitally, integrating it with coding and mapping software for immersive and interactive art installations. Here, light evolved from a simple functional tool to a dynamic, programmable element of artistic expression.5

2. Early explorations of Light and Sound in 20 century : Scriabin’s Vision of Total Art

Alexander Scriabin’s work presents a fascinating early exploration of integrating light and sound, particularly in Prometheus: Poem of Fire and his concept of the clavier à lumières ("keyboard with lights"). While my research does not focus on color as a primary element, it acknowledges the historical significance of Scriabin's use of light as part of his artistic vision. His clavier à lumières aimed to project colored lights corresponding to specific musical pitches, creating an immersive sensory experience. However, my interest lies less in Scriabin's use of color and more in his broader vision of interactive, embodied performance.

Scriabin believed in the transformative power of music and envisioned an artistic revolution capable of elevating humanity's spiritual consciousness. Inspired by Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk (total artwork) and the theosophical philosophy of Vladimir Solovyov and Helena Blavatsky, he sought to create a multi-sensory, immersive experience through his unrealized masterpiece, Mysterium. This "temple of sound and light" was imagined as a space where performers and audiences would participate collectively, erasing the boundaries between stage and audience. The interactive nature of Mysterium, with its integration of sound, light, aroma, and movement, demonstrates Scriabin’s innovative approach to performance.

Although his plans may seem fantastical, they remind me of modern interactive theater and also the ways audiences engage in performances today, such as mosh pits at metal concerts, where physical movement becomes another form of tribute to the performers.6 Scriabin’s vision of an interactive theater suggests an intimate connection between performers and the audience, where everyone contributes to the sensory environment. This idea is particularly inspiring when considering how light and shadow interact with the human body to shape the perception of performance. The immersive, almost ritualistic quality of his work parallels contemporary practices where audiences actively participate in the artistic process, blurring the line between creators and spectators.

However, my approach to sound-light interaction differs significantly from Scriabin’s. While he focused on synesthetic color-music relationships, treating light as a symbolic extension of musical harmony, my work explores light as an independent compositional tool that interacts with sound and movement in real time. Scriabin’s clavier à lumières was designed to translate pitch into fixed color associations, reinforcing the structural elements of his compositions. In contrast, I approach light as a dynamic and responsive medium—one that can shape and be shaped by performance conditions. Moreover, whereas Scriabin imagined a grand, all-encompassing artistic spectacle in Mysterium, dissolving the boundary between performer and audience through shared sensory immersion, my performances often highlight the physical presence of the performer and the interactive possibilities between light and movement. Rather than aspiring to a transcendent, spiritual experience, my work investigates the material and perceptual properties of light—how it behaves in space, how it interacts with objects and performers, and how it contributes to the dramaturgy of a piece.

Scriabin’s contributions to sound-light interaction remind us of the endless potential for performance spaces to evolve into dynamic environments. While his vision was rooted in a mystical and symbolic approach to audiovisual synthesis, my research takes a more pragmatic and exploratory stance, focusing on real-time interaction and the physicality of light in performance. By understanding Scriabin’s historical influence, I can further refine my own approach—one that treats light not as a mere accompaniment to music but as a performative force in its own right.

3. Can Light be an Instrument?

Based on my previous experiences working with light, I’ve come to realize that light is no longer just a supporting element in my pieces. It’s not simply a tool for enhancing mood or decorating the stage—it’s part of the musical discourse, sometimes even the essence of the performance. If you take away the visual aspect from light-related music works, the whole piece can lose its meaning, like a body without its spirit. This realization has led me to consider light as an instrument in its own right.

We usually think of instruments as things that produce sound—a piano, a violin, or even the simplest percussion instrument. But if we shift our perspective, does an instrument really have to produce sound? It can be any medium that conveys artistic intention,influences audience perception, and interacts with the audience. In that sense, light absolutely qualifies as an instrument. In some contemporary practices, light is used to create rhythm and dynamics much like a traditional instrument. The turning on and off of lights can establish a pulse, while gradual changes in brightness can mirror the rise and fall of musical phrases. In live performances, lighting changes can serve as cues, transitions, or emotional shifts that guide the audience’s perception of the music. For example, performances by the artist Ryoji Ikeda often feature synchronized light and sound, creating immersive audiovisual landscapes that blur the boundaries between the two senses.

The relationship between light and sound can also become interactive. In experimental works using photoresistors or solar panels, light itself directly triggers (and generates) sound, making the boundary between the visual and the auditory even more fluid. In these cases, light becomes more than just a passive visual enhancement; it becomes an active participant in the musical process. This approach brings new possibilities to interdisciplinary art, where performers can “play” light just as they would any other instrument.

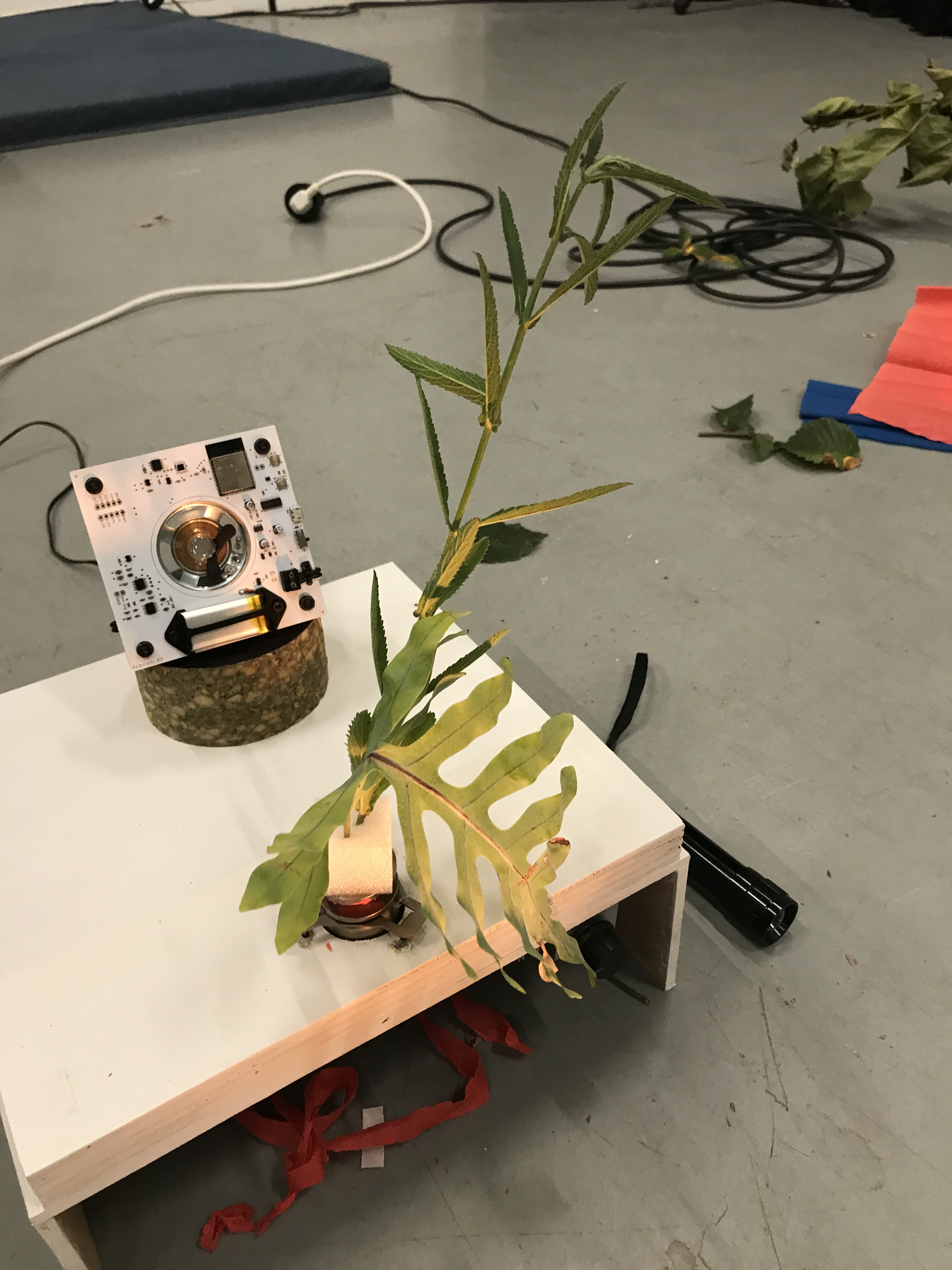

This idea became personally significant to me in 2021 when I performed Komorebi, an instrument invented by iii (Instrument Inventors Initiative), at Taiwan Culture Night at Sociëteit De Witte Den Haag. I was one of three performers playing Komorebi as an instrument, using one hand to hold it and the other to control a flashlight. Throughout the performance, we explored different ways of interacting with light, with the intensity and movement of the flashlight directly affecting the sounds produced by Komorebi. At the end of the piece, we placed Komorebi on a stand in front of a spinning motor with plants and flowers attached, allowing light and movement to merge into a final sonic and visual gesture. This was my first time performing with light in person, and it profoundly influenced how I perceive light as an active performative element.

In a broader sense, contemporary music often involves elements that cannot be fully appreciated through traditional audio recordings on platforms like Spotify or SoundCloud. Visual music,7 multimedia performances, and site-specific installations demand to be experienced live (or through formats like video), where the interplay of light and sound can be fully appreciated. Fischinger’s films demonstrate that music accompanied by visuals creates a unique form of expression, one that transcends traditional auditory compositions.

Jennifer Walshe, in "The New Discipline," explores how contemporary performance practices, especially those involving interdisciplinary elements like sound, light, and movement, continue to redefine what constitutes musical expression. Walshe’s work addresses how artists are pushing the boundaries of traditional music, challenging not only the way we perform but also what we consider to be a musical instrument. Her exploration of evolving compositional practices resonates with the use of light as an instrument, further emphasizing the fluidity between different artistic mediums in live performance.8

When we consider light as an instrument, we begin to redefine what music performance means. Making music nowadays doesn’t always have to involve producing sound at all. Instead, it can focus on creating rhythm through visual elements, conveying emotions through light, or even embracing silence and stillness as integral components, as John Cage showed us. Darkness, for instance, can be the visual equivalent of a musical pause—a moment of intentional stillness that creates contrast and focus. Playing with shadows, dimmers, and movement transforms light into a narrative tool, capable of telling a story in its own language. This challenges traditional notions of what constitutes an instrument and expands the boundaries of performance art. Nicolas Collins, in his seminal book Handmade Electronic Music: The Art of Hardware Hacking, explores how simple electronic tools, including light-sensitive components, can be repurposed in music composition and performance. Collins highlights how tools like photoresistors and lightbulbs allow artists to engage in "hardware hacking," using everyday materials to craft novel instruments that blend sound and light in many ways.9

Artists working with interdisciplinary forms have utilized light not merely as an effect but as an active medium for interaction. For example, in the work of Viola Yip, which will be explored further in Chapter II, light interacts with sound through technologies like photosensors and relays, transforming light into a tactile and responsive element of the performance. This system creates an environment where light directly influences sound production, further exemplifying how light can behave like an instrument in its own right, one that responds to human gestures and manipulations. While this example is notable, the broader landscape of light in contemporary performance showcases its growing role as a performer, alongside or even in place of sound.

In short, the use of light as a performative medium aligns with contemporary trends in performance art, where music is no longer confined to auditory experiences alone. Instead, performances often incorporate visual, spatial, and physical dimensions that demand to be experienced live or through multimedia formats. This evolution reflects a broader artistic shift, where the boundaries between sound, light, and movement blur to create immersive environments that cannot be captured in traditional recordings. In this context, light becomes an instrument not only because it contributes to rhythm, dynamics, and narrative, but also because it evokes a sensory connection, challenging us to rethink what it means to perform, compose, or experience music.

4. Interdisciplinary Art Forms with Light

Light has never been merely a tool for illumination. It is a trace of time, a memory of emotions. In various cultures and artistic disciplines, light has been constantly redefined—from the painter’s brushstrokes to architectural designs, and now in modern performance arts. Light has evolved beyond a physical presence, becoming a language of emotion, a medium for storytelling, and a central element in rituals across cultures.

Many interdisciplinary artists explore the relationship between light, space, sound, and movement. For example, Olafur Eliasson’s installations use both natural and artificial light to provoke sensory reflection. His The Weather Project at Tate Modern in London featured a massive sun-like light source accompanied by mist, recreating a natural atmosphere indoors.10 In his work, light becomes a psychological space, a temporal experience, and a reflection of human perception.

In theatre and dance, light is often used to create rhythm and narrative, becoming an integral part of the performance. Modern dance choreographer Alwin Nikolais, for instance, designed lighting as a form of "visible music," where the interplay of light and movement guides the audience’s emotional journey. In works like Crucible, dancers’ limbs appear and disappear behind a mirror, illuminated by dynamic lighting effects such as colors and slide projections. The soundtrack, composed of sound effects, and the reflections of the dancers in the mirror create an immersive illusion. Fingers, hands, and forearms emerge, bathed in red light, inviting the audience’s imagination to fill in the unseen. As the performance progresses, different rhythms, body movements, color changes, and pattern projections transform the atmosphere. Throughout the piece, the dancers are never fully revealed, emphasizing the central role of light in shaping perception and narrative.11

Robert Henke's Lumière series explores the integration of light as a primary compositional element in audiovisual performance. Initiated in 2013, the project evolved through multiple versions, each refining the synchronization between laser visuals and sound. In "Lumière I" (2013), three white light lasers were directly linked to sound generation, but this method presented challenges in achieving intuitive audiovisual coherence. "Lumière II" (2015) introduced a more advanced system, featuring colored lasers and a dedicated FM synthesis engine that allowed precise synchronization through MIDI-triggered events. "Lumière III" (2017) further expanded on this, blending improvisational energy with structured compositions.12 By decoupling sound and visual control signals while maintaining an underlying synchronicity, Henke's work redefines light as an instrument, treating it as an active agent in musical expression.

Interestingly, shadow plays have historically used light and shadow as narrative mediums. Traditional shadow puppetry tells stories through the interplay of light and darkness, creating a world between reality and imagination. Contemporary artists like Christian Boltanski reinterpret this ancient form by using light and shadow to explore themes of memory and existence.13 Shadows, as ephemeral forms born from the absence of light, evoke a sense of time passing and the impermanence of life.

In my work, I explore the intersection of light and sound as an integrated, real-time compositional element. Unlike Eliasson, whose installations create immersive visual environments, or Henke, who synchronizes light and sound through precise digital systems, my approach is rooted in the physicality of analogue oscillators and real-time performer interaction. By incorporating photoresistors and DMX-controlled lighting systems,my intention is to create performances where light is not just a medium but an active participant—generating sound, shaping spatial perception, and responding dynamically to performers. In my work, light serves as both a tangible material and a vehicle for sensibility. From natural sunlight and moonlight to meticulously designed stage lighting, every beam carries the warmth of time and memory. When light enters performance art, it no longer merely illuminates the stage but helps bridging the gap between the audience and the performance space. The language of light transcends both sound and vision, requiring no translation yet reaching deep into human perception. It can gently caress a space or strike the senses with intensity, shifting between presence and absence. As a compositional tool, light transforms space, projects memory, and challenges our perception of time. In contemporary interdisciplinary art, it is no longer an auxiliary element but a central force, sometimes even the sole performer. Through my work, I aim to push beyond traditional notions of lighting in performance, allowing it to coexist with sound, movement, and space in an evolving dialogue that invites the audience into an expanded sensory experience.

Chapter II: The Reciprocal Transformation of Sound and Light

1. Bidirectional Sound-Light Interaction

In contemporary performance, sound and light are not just complementary elements but interconnected forces capable of influencing and shaping each other in dynamic ways. Traditionally, light has been used to support music, but current artistic practices view it as an active participant, engaging in bidirectional interaction with sound. This interaction transforms performances into immersive experiences.

Although I have no formal engineering background, I have learned about the mechanics of sound and light interactions through self-study, primarily from resources provided by teachers in the conservatory and online materials.I am not focusing on the detailed workings of all these technical systems. Instead, I want to explore some methods of interaction between sound and light that I find artistically inspiring and interesting that have influenced my own artistic work. In this chapter, I will explore how I divide these interactions into three sections based on their underlying mechanics: Sound-to-Light, Light-to-Sound, and Mutual Interaction. I will illustrate each of these mechanisms with examples that I think are good representatives of this type of interaction, showing their artistic and functional importance.

- Light Responsive Systems (Sound-to-Light Interaction)

Light responsive systems are advanced technologies designed to generate and control light based on various stimuli. These systems create dynamic, interactive, and immersive lighting environments by reacting to inputs such as sound, touch, vibration, and physical motion. In this discussion, the focus is on the interaction between light and sound, which forms the core of this research.

In popular music, such as in nightclubs and discos, lighting systems often respond to the beat and rhythm of the music. This synchronization visually amplifies the music’s energy and mood, enhancing the overall experience. During live performances, lighting systems can be synchronized with both the music and the performers' movements, creating an integration of visual and auditory elements. One way this is achieved is through sound-controlled lighting circuits, where the brightness of lights is adjusted in sync with the sound captured by a microphone (or via MIDI).14 These sound-controlled light circuits are common in discos, bars, and parties, where lights react to the surrounding music in real time. A typical configuration involves the use of an electret microphone (mapping the amplitude of the music signal) to control the lighting's intensity.

Beyond music, this interaction is also present in theme parks, where sound-responsive lighting enhances rides and shows. Fireworks displays, such as those at major events like the New Year's Eve celebrations, often feature lights that explode in perfect sync with musical scores. In everyday life, sound-to-light systems can be found in home décor, such as LED strips that change color based on background music, or in children’s toys that light up when they make noise. These examples show how the connection between light and sound is deeply integrated into both artistic expression and everyday experiences.

- Sound Responsive Systems (Light-to-Sound Interaction)

Technologies like photoresistors and solar panels allow performers to translate light variations into sound. In "Forcefield" by Hugo Morales Murguía, performers manipulate flashlights to alter sound textures via light-sensitive circuits and photovoltaics.15 Additionally, the piece consists of the movement of four performers around a rotating light. Each performer wears a solar panel on their chest, which produces a sound whenever the rotating light hits it. The signal of each panel is routed to a quadraphonic system placed around the audience, who are seated right outside the performance area. The sound generated by the light in combination with the moving panels creates a form of “physical human sequencer.” Furthermore, each performer uses three sorts of handheld lights that they direct to their own panel, creating another layer of sound interacting within the sonic environment. These systems enable artists to explore new forms of expression beyond conventional auditory experiences.

Another example of light-to-sound interaction is "In Memoriam Michel Waisvisz" (2009) by Nicolas Collins. In this piece, a candle's flickering flame controls the tuning of four oscillators, transforming subtle variations in light into shifts in pitch. The performer influences the flicker using a small fan, introducing an element of physical interaction that disrupts the light source and alters the sound. This approach highlights the organic and unpredictable nature of light as a musical parameter, where the oscillators respond dynamically to real-time fluctuations. Similar to "Forcefield," this piece demonstrates how light can function as an active component in sound production and a fundamental part of the musical process.16

- Simultaneous Sound-Light Systems (Mutual Interaction)

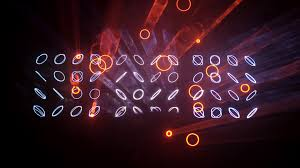

Some works generate sound and light from a shared source, ensuring perfect synchronization. In works like "Test Pattern" by Ryoji Ikeda, sound and light are generated from the same data source. In this piece, Ikeda uses a combination of digital audio signals and visual patterns derived from the same dataset, creating a unified sensory experience. The sound and light patterns evolve together, reinforcing each other and producing an immersive environment. The composition of both light and sound as an intertwined entity offers a deep exploration of perception, demonstrating how visual and auditory elements can function as equal partners in a performance. Through this approach, "Test Pattern" highlights the potential of light to be more than a passive component in music, instead presenting it as a dynamic, compositional tool.17 The use of video as light such as in "Test Pattern" has further expanded my interest in how visual elements can enhance live performances. I will elaborate on these ideas and their influence on my work in the next chapter.

Another example is "錯置現象" ("The Displacement") (2013) by Lien-Cheng Wang. This piece scatters musical instruments and speakers across the performance space, with sound and light emanating from all directions. The audience experiences an immersive environment where they can freely explore different auditory and visual effects by moving through the space. The performance combines electronic sounds, computer composition, and traditional percussion instruments, creating a complex interplay between digital technology and live performance. Wang’s work emphasizes the spatialization of musical instruments and the relationship between sound, space, and light, offering a unique exploration of how technology can extend the possibilities of solo percussion performances.18

2. Light Devices and Sources in My Composition

In relation to some of the systems mentioned above, in my compositions, I have explored the use of light not just as a visual element but also as an active, dynamic source of sound. This experimentation has led me to incorporate several innovative devices that utilize light to influence and create both sound and performance.

- Photovoltaics: Solar Panels as Microphones

One such device is the solar panel, which I employed in my piece "Stages" (2024). For this composition, I repurposed the solar panel as a microphone to produce direct sound. The solar panel reacts to variations in light intensity, generating electrical signals that create distinctive noise. In "Stages," I assigned the harpist to press a pedal that triggers a white screen light via a projector. Instead of displaying images, the projector is used solely for its light, emitting sharp, urgent flashes. The solar panel, positioned in front of the projector, responds to these bursts, generating sound that accompanies the percussion set. The resulting chaotic texture—produced by mallet strokes on the harp and the interplay between the solar panel and the intense light bursts—forms a central element of the piece, merging visual intensity with sonic volatility.

This approach is reminiscent of Ryoji Ikeda’s innovative work, where video screens serve as enormous light projectors. In Ikeda’s installations, the video screen is not merely a display but a powerful light source that produces pulsating beams which act as both visual and sonic material. Like Ikeda, I treat light as an active force rather than a secondary effect; the light from the projector is integral, directly influencing the sound generation. This method challenges conventional boundaries between sound and light, demonstrating that light can be manipulated much like a traditional instrument.

- Amplifying Light: Using Contact Microphones to Articulate Light

By utilizing a four-channel dimmer in "Belling in Sunrise, Drumming in Twilight" (2022) I was able to create intricate light patterns that influence the rhythm of the oscillator. In this composition, I used the dimmer to control four spotlights, adjusting their intensity and creating shifting light patterns. These light patterns act as a rhythmic guide for the oscillator, triggering different pitches and rhythms based on the light they receive through a light sensor (photoresistor). By gradually switching between different light patterns, I was able to manipulate the light’s rhythmic structure, creating an evolving interplay between light and sound. As I controlled the dimmer, I shaped both the sonic and visual components of the piece, allowing the lights to dictate the oscillator’s behavior while also establishing a dynamic atmosphere on stage.

In "Stages" (2024), I incorporated contact microphones attached to the crotales. When the percussionist strikes the crotales, the vibrations are picked up by the contact microphones and, through Max MSP, transformed into a signal that triggers four spotlights positioned behind the performers. The contact microphones amplify the sounds of the crotales, and the Max MSP system processes these signals, converting them into light cues that activate the spotlight. This interaction between sound and light heightens the visual and auditory intensity of the piece, creating a connection between the physical act of striking the instrument and the sudden shift in lighting, amplifying the emotional impact of the performance.

The photoresistor-controlled oscillator, the solar panel, the light dimmer, and the contact microphone with spotlight trigger are just a few examples of how I use light as an active component in my compositions. These devices and techniques highlight the potential of light to directly influence sound production, turning light into a dynamic, responsive instrument that shapes the auditory experience. In works like "Belling in Sunrise" (2022) and "Drumming in Twilight and Stages" (2024), light patterns not only create visual effects but also play a crucial role in driving the rhythm and frequency of the sound. These works showcase my ongoing research into light as both a compositional tool and a sonic instrument, challenging the traditional roles of light and sound in performance. These processes will be analyzed and described in more depth in Chapter III.

- Oscillators and Photoresistors as Light-Sensitive Devices

Another device I have used is an analogue oscillator with a photoresistor, which is popularized by Nicolas Collins in his book Handmade Electronic Music. In this setup, the pitch of the oscillator is proportional to the amount of light it receives. When light levels are low, the oscillator produces discrete pulses. As the light intensity increases, these pulses accelerate and merge into a perceivable pitch. The oscillator operates using a triangle wave, creating smooth, evolving tones that respond sensitively to changes in light intensity. For me, the sound produced by the oscillator is a low, raw tone—its deep, resonant quality pairs well with metallic or skin sounds, adding texture and complexity to the overall sonic landscape.

Additionally, in my piece "Pressure Tree" (2023), I expanded on the idea of the oscillator, but this time without using light. Instead, I replaced the photoresistor with two open cables, cutting the ends to expose the wires, which I used as brushes on an A1-sized paper to create a painting. The method works by using the conductivity of the ink and water on the paper, which is picked up by the two brushes, to determine the pitch of the oscillator. This creates a unique interaction between the visual art and the sound, making the oscillator's pitch change based on the conductivity of the materials on the paper. This approach showcases how the concept of the oscillator can be adapted and expanded in creative and unconventional ways.

3. The Intergration of Sound, Light, and Movement

In my compositions, I find that the integration of light and sound alone sometimes lacks the excitement of live performance that I am striving for. Without performers actively interacting with these elements, a piece can easily become more like an installation rather than a musical performance. For me, the core of a live performance is the dynamic interaction between the performers, their physical presence, and the expressiveness that comes from their movements. This is why movement has become a very important part of my work, as it not only enhances audience engagement but also helps shape the musical narrative.

While working on "Belling in Sunrise, Drumming in Twilight" (2022), I faced challenges when trying to notate (the sound/actions) of the oscillator, especially in the second movement, where the oscillator plays solo. To solve this, I started thinking about how to incorporate movement and began experimenting with choreography. I was inspired by Taichi, with its slow, meditative movements, and thought about how the performer’s body could help express the light and sound in a more natural and immediate way. This approach not only helped me resolve the problem of notating the oscillator but also created a direct connection for the audience to engage with the music. The choreography allowed the music to be visualized and performed, offering the audience a clearer understanding of the music through both what they see and hear. Since then, movement has become increasingly important in my compositions—not just as a solution to technical challenges, but also as a way to bring life to the performance, creating a true, unfolding experience on stage.

The work of Viola Yip: Blurring the Boundaries of Sound, Light, and Movement

With this in mind, I am inspired by the work of composers like Viola Yip. Her unique way of combining light, sound, and movement—where the boundaries between the body and audiovisual elements are blurred—challenges and expands my understanding of how these components can work together in a performance.

Viola Yip is an experimental composer, performer, sound artist, and instrument builder whose work reimagines the boundaries between sound, light, and the body in live performance. Her practice challenges conventional notions of musical composition by integrating light as an active, responsive element, rather than a static visual accompaniment. In doing so, she explores how audiovisual performance can extend beyond traditional instruments and notation, creating immersive and multisensory experiences.

Central to Yip’s approach is the idea that the body is not just a vehicle for producing sound but an integral part of the audiovisual composition itself. In her experiments, she builds instruments that transform physical movement into sound and light interactions. One of her earliest explorations involved placing a sensor on a table while holding two light bulbs in her hands. By adjusting the bulbs' proximity to the sensor, she could manipulate sound parameters in real time. This experiment underscored the role of the body as an expressive force in the performance—not just activating the instrument but becoming an inseparable part of the audiovisual composition. Unlike traditional instrumental performance, where bodily movement is often a byproduct of sound production, Yip’s work makes movement a primary compositional element, blurring the line between sound, gesture, and light.

This emphasis on bodily presence, however, is not a fixed rule in her work. In some projects, Yip moves away from physical performance entirely, shifting focus toward the interplay of light and shadow. Her recent Bulbble variation piece with flowers shadows is a striking example, where she eliminates her own presence on stage, allowing the movement of shadows to take precedence. Instead of a performer manipulating sound and light, the composition unfolds through shifting light angles, casting complex floral patterns that evolve over time. This shift raises a fundamental question: Can light itself perform? In removing the performer, Yip allows light and shadow to act as the primary agents of transformation. While this contrasts with her previous works that foreground bodily interaction, it still follows the same philosophy—treating non-sonic elements as musical material.

The contrast between these two approaches—one where the body is central, and one where it is absent—raises interesting parallels and distinctions with my own work. In my performances, movement functions as a choreographic element within the audiovisual system. The body is not just a controller or trigger but an expressive force that exists together with light and sound. In pieces like Shadows in Three, I explore how physical gesture interacts with electronic and light-responsive elements, making movement an inseparable part of the composition. Yip’s work challenges me to consider different perspectives: How does the removal of the performer alter the audience’s perception of sound and light? Can a performance exist without a visible performer at all? Moreover, Yip’s approach to light resonates with my own exploration of its role beyond illumination. Both of us use light as a dynamic, compositional force rather than a static effect. However, while Yip’s Bulbble (2019) translates light intensity into musical structures via relays and photosensors, my research often focuses on the bidirectional interaction between sound and light—where one element actively influences the other in a continuous feedback loop.19 Her emphasis on shadow as a performative medium also raises intriguing possibilities for my work: Can shadows function as a counterpart to sound, just as light does? Could the absence of light be as expressive as its presence?

Through her unconventional mapping of light, sound, and movement, Yip expands the vocabulary of interdisciplinary performance, offering new ways to think about embodiment, absence, and audiovisual interaction. Her work challenges the notion of what constitutes an instrument and where performance begins and ends. In examining her practice, I find new ways to reflect on my own approach—on the role of movement as choreography, the agency of light in composition, and the ever-fluid relationship between performer, space, and technology.

Chapter III: Applications in My Music Practice

In this chapter, I will delve deeper into the practical applications of light-sound interactions in my compositions, building upon the foundational concepts and examples introduced in the previous chapter. By exploring specific pieces such as "Stages" (2024), "Pressure Tree" (2023), and "Belling in Sunrise, Drumming in Twilight" (2022), I will analyze how light is not merely a visual element but an active, dynamic component that influences sound production and performance. This chapter will examine the technical and creative processes behind these works, highlighting how light-responsive systems and innovative devices like solar panels, photoresistors, and contact microphones with DMX spotlights are integrated into my compositions. Through this analysis, I aim to demonstrate the potential of light as a compositional tool and sonic instrument, challenging traditional boundaries between visual and auditory elements in music.

1. "Belling in Sunrise, Drumming in Twilight" (2022)

Introduction

"Belling in Sunrise, Drumming in Twilight" (2022) marked the beginning of my exploration into integrating light as a compositional tool. Composed during my bachelor's studies as part of the KOnstruct 22 project, the piece is designed for four percussionists and two light-based oscillators with live electronics. It is divided into four movements, each with its own unique approach to light, sound, and movement.

Movement 1: Darkness and Sound Exploration

The first movement is characterized by minimal light, emphasizing silence and subtle sounds. The stage is mostly dark, with only a faint glow from an LED candle. This movement is about sound exploration and serves as a listening session for the audience. The oscillators and other percussion instruments, such as vibraphones, wooden sticks, and singing bowls, create delicate pulses that invite the audience to focus on the nuances of the sounds. The low light level guides the audience's attention, creating a sense of anticipation and intimacy.

Movement 2: Solo with LED Candle and Oscillator

The second movement is a solo for the oscillator and LED candle. The performer executes a choreography inspired by Taichi, holding the LED candle in one hand and a photoresistor in the other. The movements are fluid and graceful, with the light from the candle interacting with the photoresistor to generate sound for the oscillator. A plugin sound effect is used to modify the oscillator's sound, making it more airy and flowing, complementing the Taichi-inspired movements. This section highlights the interplay between light and sound, with the performer's actions directly influencing the sonic output.

Transition Between Movements 2 and 3

Between the second and third movements, there is a brief transition where the soloist brings the candlelight to the bass drum. As the candlelight is extinguished, a spotlight suddenly illuminates the bass drum, signaling the start of the next movement. This transition is crucial in maintaining the flow of the performance and preparing the audience for the upcoming section.

Movement 3: Drumming and Choreography

The third movement features all four percussionists gathering around the bass drum for a powerful drumming session. The performers' movements are choreographed, adding a visual dimension to the auditory experience. The drumming is intense and rhythmic, with the percussionists' actions synchronized to create a cohesive and dynamic soundscape. This section emphasizes the physicality of the performance and the unity of the ensemble.

Movement 4: Interplay of Light and Sound

In the final movement, two of the percussionists move to the back of the stage, standing in front of two background boards with their hands steadily placed, sensors facing the spotlights. The other two percussionists continue playing the bass drum. The spotlights, connected to a light dimmer pack, create different patterns that produce varying rhythms. The interplay between the programmed spotlight patterns and the live sound manipulation creates a dynamic and engaging audiovisual experience. The sound engineer and I sit at the back of the audience, controlling the light and sound effects in real time, ensuring a seamless integration of the visual and auditory elements.

Light Design

The light design in this piece played a significant role in shaping both the sound and the visual experience. LED candles, eight spotlights connected to a dimmer pack, and top-down theater spotlights projected onto the bass drum were carefully integrated. In the first part, low light created a sense of pause, shaping the mood and guiding the audience's attention. The second part featured the soloist's LED candle and photoresistor interaction, where the choreography and light formed the primary focus. The final section’s spotlight rhythms, programmed through the dimmer pack and manually controlled during the performance, added layers of visual rhythm, complementing the sonic patterns. Through this process, I realized that light not only interacts with sound but also serves as a powerful theatrical element, guiding the audience’s focus and enhancing their experience. Thoughtful placement of light is especially crucial for transitions between scenes, as it creates a seamless flow and draws attention to key moments on stage.

Insights and Reflections

This piece taught me valuable lessons about using light as both a compositional and theatrical tool. I discovered that light could interact with sound to create dynamic textures but could also serve as a visual element that guides the audience’s focus. The use of LED candles and spotlights emphasized the importance of precise light placement, especially during transitions between sections.

Additionally, working with raw oscillator sounds, such as triangle waves, revealed challenges in blending them with acoustic instruments. Experimenting with oscillators first, instead of deciding the instrumentation upfront, represented a new compositional approach for me. The process highlighted the need for flexible solutions, particularly in addressing technical issues like malfunctioning oscillators, cables, and dimmer packs.

Finally, incorporating choreography in the second part, where the notation relied on movement rather than traditional scores, offered performers more freedom to focus on sound quality and stage presence. This experience helped me understand the potential of light to create emotional and structural coherence in a performance, setting the foundation for future explorations in sound-light interaction.

2. "Shadows in Three" (2023)

Introduction

"Shadows in Three" (2023) was my second participation in the KOnstruct project, created during my master’s studies. This piece draws inspiration from traditional Taiwanese shadow theater (皮影戲), but instead of using paper puppets, I chose to have three percussionists use their bodies—hands and faces—to create a more direct connection between sound and visual elements. The concept was also influenced by a poem from Li Bai (李白): "舉杯邀明月,對影成三人" (Raising a cup to invite the bright moon, facing shadows to form a trio), where the poet imagines himself drinking with his shadow and the moon, forming a trio.

The setup included a bass drum skin suspended vertically on a large tam-tam frame, acting as a screen for shadow play. A contact microphone attached to the bottom captured the sound of hands striking the drum skin. The piece is divided into three parts. The first introduces the performers’ faces and hand gestures with alternating light on and off, creating a mysterious visual atmosphere without sound. In the second part, the performers begin to produce rhythms and patterns by striking the drum skin, guided by choreographed movements. The final section adds a second layer of blue light, representing the moon, as the sound is enriched with live electronic effects and a photoresistor-connected oscillator, generating raw, textured sounds.

Light Design

The light design for "Shadows in Three" was simple but intentional, using two light sources: a yellowish spotlight connected to a dimmer and a circular LED light set to blue. These lights played distinct roles in shaping the mood and guiding the narrative of the performance. The yellow spotlight highlighted the performers’ hand movements and facial structures, creating sharp contrasts and vivid shadows on the bass drum skin. This interplay of light and shadow directly informed the audience where the sound originated, enhancing the sound-visual connection.

In the final section, the addition of the blue LED light transformed the atmosphere, embodying the poetic imagery of Li Bai’s moonlit scene. Although the design used minimal equipment, we experimented with angles, intensity, and timing to achieve the most striking and theatrical effects. The simplicity of the setup allowed the shadows and their interaction with sound to take center stage, emphasizing clarity and focus over complexity.

Notation and Choreography

The notation for this piece is handwritten, which allowed me to integrate choreography for the hands and faces directly into the score. Above the staff, I included a small circle representing the drum skin (screen), using different colors to represent different performers. Arrows indicated the starting positions and movements of the performers on the screen. This approach provided a clear visual guide for the performers while allowing for expressive movement.

The choreography was carefully designed to blend with the rhythmic parts, and for the notated sections, I used traditional rhythm notation alongside graphic elements to indicate the performers’ hand movements. This combination provided clarity while allowing space for expressive movement.

Insights and Reflections

Building on lessons from my previous work, I intentionally kept the instrumentation minimal in this piece to avoid overloading the sound texture. Instead, I relied on electronics to add depth and dimension when needed. Collaborating with Simon Kalker as our sound engineer, we integrated live electronic processing to complement the acoustic elements. This approach highlighted the balance between simplicity and richness in sound. The choreography was carefully designed to blend with the rhythmic parts, and for the notated sections, I used traditional rhythm notation alongside graphic elements to indicate the performers’ hand movements. This combination provided clarity while allowing space for expressive movement.

This project reinforced my desire to create pieces that are not only aurally engaging but also visually striking. The shadows served as a crucial storytelling element, bridging the gap between the auditory and visual experiences for the audience. Through this work, I discovered that light can function as more than just an accessory; it is a vital compositional tool that enhances the narrative and emotional impact of a performance.

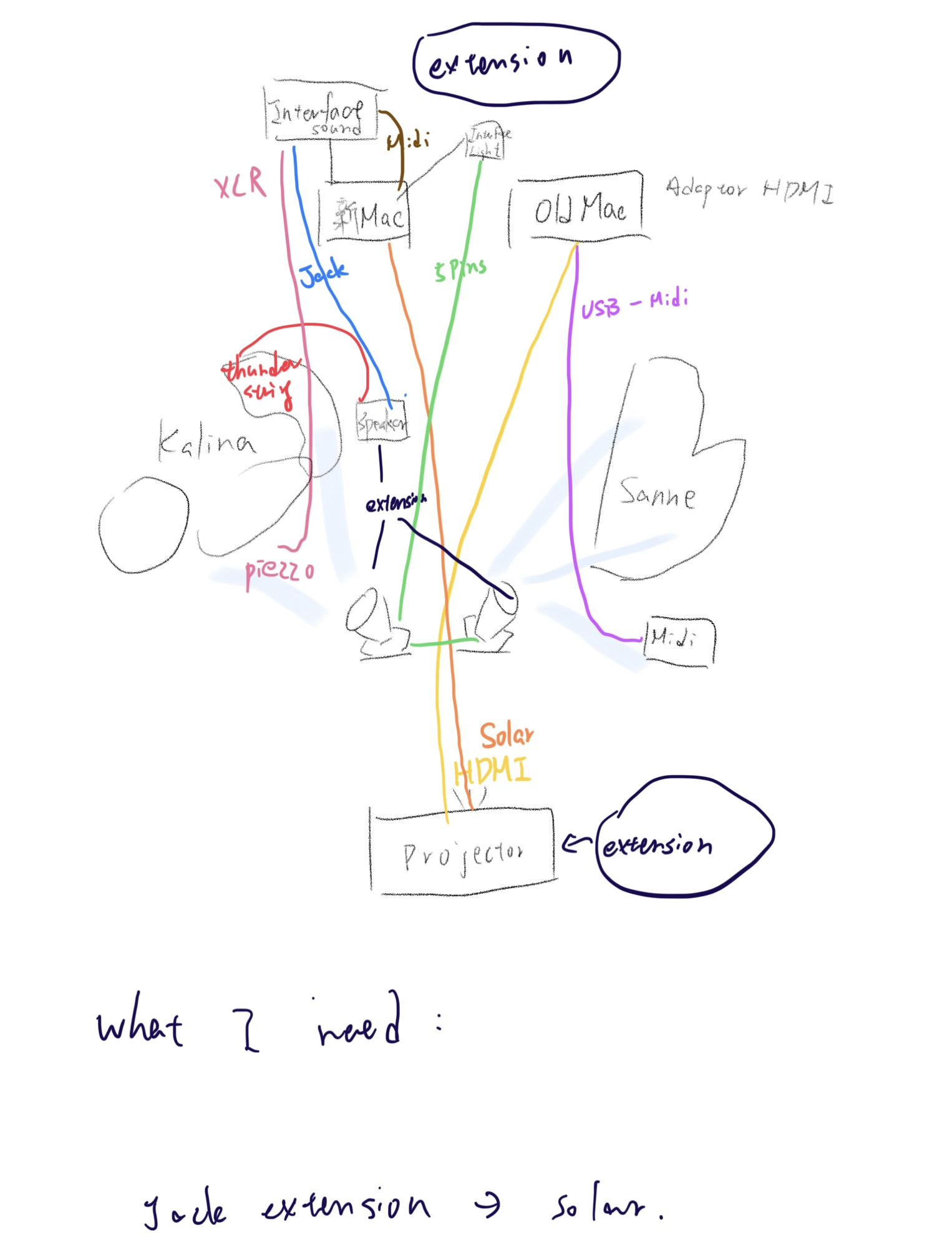

3. "Stages" (2024)

Introduction

"Stages" (2024) is a piece I composed for harp and a variety of percussion instruments, including pipes, gongs, crotales, woodblocks, tom-toms, a floor drum, a side tom-tom, a thunder string, and timpani (with superball). This work was created for the final master exams of Sanne Bakker and Kalina Vladovska, who are both very interested in multimedia and contemporary works. The inspiration for this piece came from the devastating earthquake that happened on April 3, 2024. During the trial sessions, I tried to combine ideas of light, sound, and electronics. We experimented with a solar panel connected to a projector, controlled by a pedal operated by the harpist, and a contact microphone connected to the crotale stand to trigger spotlights. However, these elements did not come together as one cohesive piece. The earthquake inspired me to think about the chaos and the silence between different stages, with the light representing the contrasting scenes one might witness during such an event.

Light Design

The light design for "Stages" is divided into two parts, each serving a distinct purpose in the composition:

-

Solar Panel as Microphone: The solar panel detects light and produces noise directly. I connected a pedal from a projector to the harpist, allowing them to press the pedal and change the slides. The projected image is not a traditional image but rather a stark contrast of white and black, creating a bold, square-like light effect. This part aims to depict the chaotic situation, with the harpist using a mallet to strike the harp, which is prepared with bells hanging on the top of the low strings. The light from the solar panel is intended to be impactful and shocking, mirroring the random noise (white noise) produced by the harp. Simultaneously, the percussionist improvises on the tom-tom and thunder string, adding to the chaotic atmosphere.

-

Contact Microphone and Spotlights: A contact microphone attached to the crotale stand sends signals to Max/MSP, which then triggers four spotlights behind the players, facing the ceiling. This part is more delicate and silent, featuring soft harp, crotale, and woodblock sounds. The crotale, with its rich harmonics and echoing sound, provides a stark contrast to the noise of the first part. The spotlights are programmed with a delay effect, so after the strike of the crotale, the light remains on for 0.5 seconds and then fades out over the next 0.5 seconds. This creates a visual echo that complements the harmonic and echoing qualities of the crotale, enhancing the delicate and serene atmosphere of this section.

Performance and Audience Reception

We first performed the piece for Sanne's exam using only two spotlights facing the audience. However, the strong light beams were uncomfortable for the audience, who were not expecting such intensity. For the second performance, we switched to four spotlights facing upwards towards the ceiling and positioned behind the performers. This adjustment created a more immersive and less intrusive lighting experience.

Challenges and Learning

The mapping of all audio, lights, projection, pedal, and microphone elements was incredibly challenging. In this piece, I was not only composing but also acting as a technician, which allowed me to learn a great deal about the technical aspects of multimedia performance. The experience was demanding but also highly rewarding, as it expanded my skill set and deepened my understanding of integrating light and sound in contemporary works.

Insights and Reflections

I was not so satisfied with the piece and felt completely ashamed after the concert. However, some people really liked it and asked Kalina for my contact information to commission new pieces. Even a harpist in Florida asked to perform this piece at a contemporary music festival there. I was totally shocked.

Looking back, I think there are areas I would improve in the piece. The notation is very simple, but the harpist and percussionist have a lot of complex rhythmic counterpoint, which makes it challenging for them while the audience couldn't hear it well, I guess (since no one mentioned it after the concert). I think another approach, like simple notation but complex sound, could be more effective.

Chapter IV: Conclusion. Expanding the Horizons of Light and Sound Integration

This research explores the integration of light as a compositional element in contemporary music, using it as an active force that interacts with sound and performance. Through works such as "Belling in Sunrise, Drumming in Twilight," "Shadows in Three," and "Stages," I have examined how real-time electronics and interactive lighting shape musical perception, spatial awareness, and performance dynamics. The bidirectional interaction between sound and light—whether through oscillators responding to light or sound-triggered lighting—demonstrates how these elements influence musical structure and expression. By analyzing historical and contemporary approaches, this research highlights how light can function beyond traditional stage design, becoming an essential part of musical composition.

Building on these ideas, I am currently developing a new project with Bl!ndman string quartet, where I integrate DMX lighting to react in real time with each string play. This work will premiere at the 2025 Spring Festival, further advancing my research into dynamic light-sound relationships. Additionally, I am excited about the opportunity to collaborate with a professional light artist in the Pictures in the Exhibition project. This project involves composing a piece inspired by a painting for percussion and piano duo, which will later be included in a full film production directed by percussionist and filmmaker Konstantyn Napolov. This collaboration will allow me to expand my understanding of light design in performance. At the same time, I am exploring the role of light in connecting different artistic disciplines within a concert setting. In "Cello from West to East," a production featuring cellist Sheng-Chun Lin, dancer Jae Eun Jung, and walking/visual artist Chun-Yao Lin, I aim to use light as a unifying element between music, movement, and spatial expression. These ongoing projects reflect my commitment to deepening the relationship between sound and light in performance, and I look forward to discovering new possibilities through future collaborations and creative experiments.

Ultimately, this research underscores the potential of light as a compositional tool, expanding the boundaries of contemporary music by integrating it with sound in ways that create new forms of artistic expression. Moving forward, I hope to continue refining these concepts and developing new methods for light to interact with sound, space, and performance in meaningful and innovative ways.

Bibliography

Alpers, Svetlana. The Art of Describing: Dutch Art in the Seventeenth Century. University of Chicago Press, 1983.

Street Art Museum Tours. "Exploring the Artistic Genius of Johannes Vermeer: A Journey Through His Masterpieces of Light and Color." Blog. Accessed March 1, 2025. https://streetartmuseumtours.com/blogs/blog/exploring-the-artistic-genius-of-johannes-vermeer-a-journey-through-his-masterpieces-of-light-and-color.

Artforum International. "Olafur Eliasson: The Weather Project." Artforum, 2004. https://olafureliasson.net/artwork/the-weather-project-2003/.

Prague Youth Theatre. "A History of Lighting Design: From Sunlight to Stage Light." Prague Youth Theatre Blog. Accessed March 2, 2025. https://pragueyouththeatre.wordpress.com/2019/09/17/a-history-of-lighting-design-from-sunlight-to-stage-light/.

University of Bristol. "The Chamber of Demonstrations: Reconstructing the Jacobean Indoor Playhouse." Drama Department. Accessed March 2, 2025. https://www.bristol.ac.uk/drama/jacobean/research3.html.

Brockett, Oscar G., and Franklin J. Hildy. History of the Theatre. 11th ed. Boston: Pearson, 2010.

Brougher, Kerry, et al. Visual Music: Synaesthesia in Art and Music Since 1900. Thames & Hudson, 2005.

Cage, John. Silence: Lectures and Writings. Wesleyan University Press, 1961.

Chion, Michel. Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen. Columbia University Press, 1994.

Collins, Nicholas. Handmade Electronic Music: The Art of Hardware Hacking. New York: Routledge, 2006.

ElectroSchematics. "Sound Controlled Lights Circuit." Accessed March 3, 2025. https://www.electroschematics.com/sound-controlled-lights/.

Evers, Frans. The Academy of the Senses: Synesthetics in Science, Art, and Education. 2012.

Guarnieri, Massimo. "The Rise of Light." Paper presented at the 2015 ICOHTEC/IEEE International History of High-Technologies and their Socio-Cultural Contexts Conference (HISTELCON), August 2015.

Henke, Robert. "Lumière." Accessed March 3, 2025. https://roberthenke.com/concerts/lumiere.html.

Holmes, Thom. Electronic and Experimental Music: Technology, Music, and Culture. Routledge, 2020.

Ikeda, Ryoji. "Datamatics [Ver. 2.0]." Performance Notes, 2018.

Ikeda, Ryoji. Test Pattern. Accessed February 25, 2025. https://www.ryojiikeda.com/test-pattern/.

iii Collective. "Komorebi: An Instrument That Translates Light into Sound." Instrument Inventors, 2023. https://instrumentinventors.org/instructions3/.

Moritz, William. "The Dream of Color Music, and Machines That Made It Possible." Animation World Magazine 2, no. 1 (April 1997). Accessed January 5, 2025. https://www.awn.com/mag/issue2.1/articles/moritz2.1.html.

Moritz, William. Optical Poetry: The Life and Work of Oskar Fischinger. Indiana University Press, 2004.

Nichols, Rob. "A Brief History of Visual Music." Farsi Design Studio, March 4, 2020. https://www.farsidestudio.com/articles/what-is-visual-music.

Nyman, Michael. Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond. Cambridge University Press, 1999.

"Alwin Nikolais." Numeridanse. Accessed March 3, 2025. https://numeridanse.com/en/publication/crucible/.

Smithsonian Institution. Handbook of North American Indians: Plains. Vol. 13. Edited by Raymond J. DeMallie. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, 2001.

Voegelin, Salome. Listening to Noise and Silence: Towards a Philosophy of Sound Art. London: Continuum, 2010.

Walshe, Jennifer. The New Discipline. 2016. https://www.jenniferwalshe.com/writings/TND.html.

Wang, Lien-Cheng. 錯置現象 (The Displacement). 2013. https://soulblighter0122.blogspot.com/p/blog-page_17.html.

Yip, Viola. Interview by Katherine Teng. Zoom meeting, November 19, 2024.

Yip, Viola. "Biography." Viola Yip Official Website. Accessed November 20, 2024. https://www.violayip.com/bio.