Clef Notation

Bach’s terminology is not the only way to keep the recorder and traverso apart. His use of clefs often provides confirmation, given that Bach used a different clef for each of the two woodwinds.

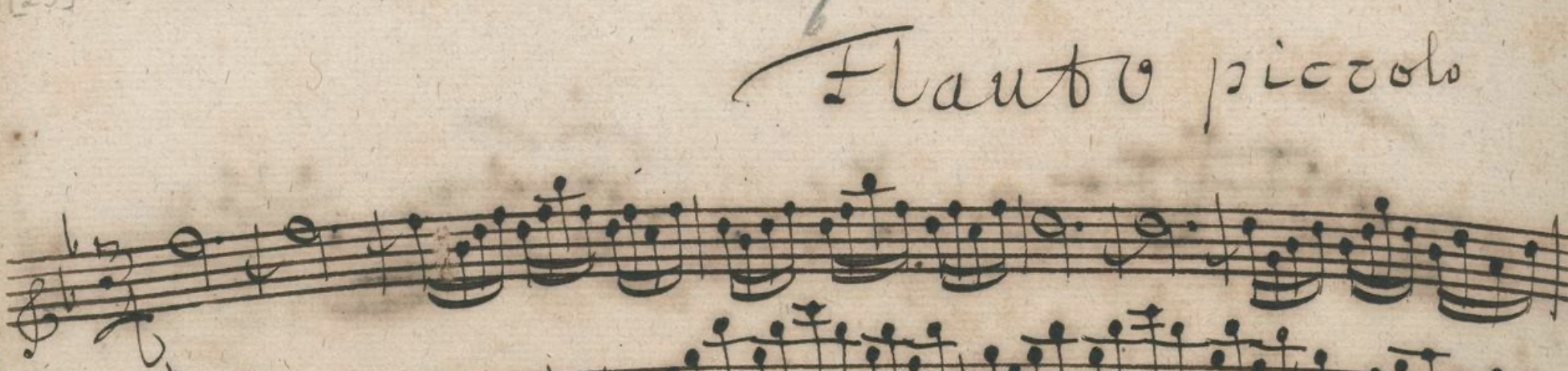

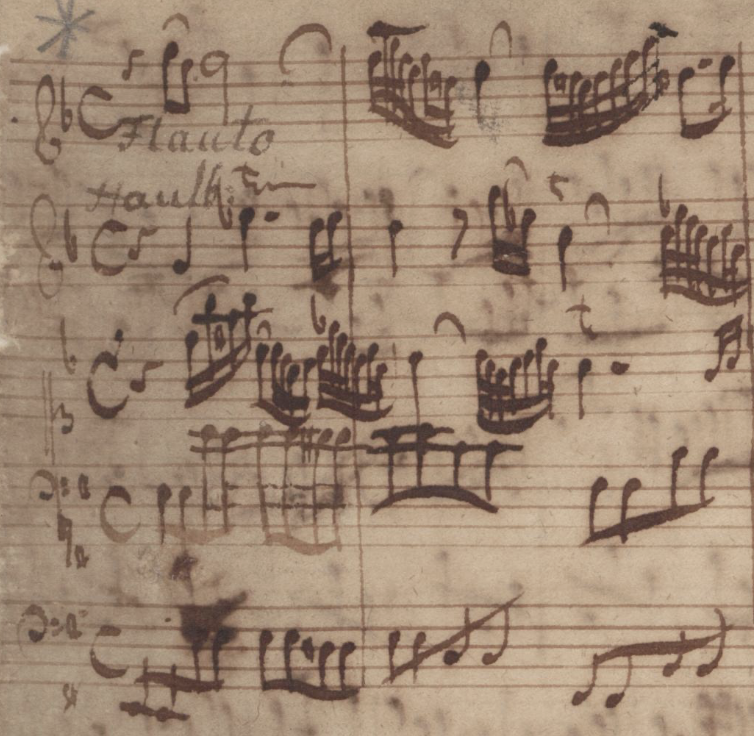

Bach used the French violin clef (g1 on the first line) for the recorder. One of the advantages of this practice was that Bach would need fewer ledger lines when he wrote for the recorder's high register, as he frequently did. This practice can be traced back to the Renaissance, when “clefs and clef-combinations served, in part, as compositional tools to regulate vocal (and instrumental) ranges”.1 Writing the recorder part in the French violin clef was common in Germany and France during the Baroque period, and even continued into the 19th century, as can been seen in the Musikalisches Lexicon from 1802 by German theorist Heinrich Christoph Koch (1749-1816): "Weil es mehr Höhe als Tiefe hat, so pflegt man die Notenstimmen für dasselbe in den französischen Violinschlüssel zu schreiben, um bey den höhern Tönen der vielen Nebenlinien der Noten überhoben zu seyn."2

The traverso on the other hand is always notated in the treble clef (g1 on the second line) by Bach. His contemporaries followed the same pattern, as can be seen in the duets from Telemann’s Der getreue Music-Meister (1728-1729). In this collection,3 the version for two Flauti dolci is notated in the French violin clef, and the version for two Flauti traversi is written in the treble clef.

The flauto piccolo parts from both BWV 96 and 103 are written in the French violin clef, confirming the need for a recorder. Confusingly, the flauto piccolo part from BWV 8 is written in a treble clef. Of BWV 8, two different versions were written. One in E major from 1724 (BWV 8.1) and one from 1746/47 in D major (BWV 8.2). The original parts of both versions have survived. Although there is no original score, a copy by Carl Friedrich Barth (1734-1813) from around 1755 has survived.4 In this score, there is no mention of a flauto piccolo. The original flute part of the E major version, a manuscript copy by Christian Gottlob Meissner (1707-1760), is marked as Fiauto piccolo, written in D major and in the treble clef. However, a big cross has been drawn over this part,5 with the indication to play from another sheet. This sheet is marked Travers and is also written in the treble clef, but this time in E major. In addition, several alterations have been made to this traverso part. According to the German musicologist Helmuth Osthoff (1896-1983),6 these alterations were possibly made by an anonymous traverso player who would perform this piece. This presumed performer has transposed some passages an octave down to avoid playing too many notes above e3. These alterations can be seen in the Neue Bach-Ausgabe of BWV 8.1 (E major version).7

In my opinion, there is a good possibility that Bach wrote the crossed-out recorder part from BWV 8.1 with an excellent recorder player in mind, but that this expert, due to illness or otherwise, was not able to play during the performance.8 Another, less talented, player had to stand in for him. Not only did this new player have to perform the cantata on traverso instead (perhaps he was not so skilled on the recorder), he also was not very comfortable playing higher than e3, resulting in the alterations he made to the 1st and 4th movements.

This poses a strong dilemma: should BWV 8.1 be played on recorder or traverso? As an instrumentalist, I am convinced that the 1st movement would work best on a recorder in a1, or third flute, given that the tessitura is a1-e3. Although it is rather high, it would also be possible to play the 1st movement on the traverso, as it is often done. However, it seems strange to me that in this version on traverso, the bottom notes d1 until g♯1 would not be used at all.

The 4th movement of BWV 8.1 has a much larger range of e1-a3. Although this would fit on the traverso, it would be exceptionally high. The movement would be perfect for the recorder in a1, if not for the few notes below a1 at the end of the movement. Since these low notes would be hardly audible anyway and could gently be omitted or transposed (as might have been done, had the flauto piccolo player been available), I find a performance of this movement on the recorder in a1 more convincing. The final choral can either be played on traverso (in 8va) or on the recorder in a1, playing an octave higher than in the 1st and 4th movement.

Pitch

In the second half of the 17th century, the popular French instruments spread out over Europe. At first these low-pitched woodwinds were imported by the French musicians themselves, but soon they were copied and adapted by the local instrument makers. In Nuremberg, Germany, Johann Christoph Denner (1655-1707) and Johann Schell (1660-1732) “applied for permission from their guild to make and sell Hautbois and Flûtes douces” in 1696.9 French low-pitched woodwinds thus encountered the higher German pitch.

To accurately discuss the different pitches around J.S. Bach, I will make use of the same system as the American/Canadian oboist, recorder player, and musicologist Bruce Haynes (1941-2011) used in his A History of Performing Pitch from 2002:10

Johann Joachim Quantz (1697-1773) wrote that “the high Chorton began to be replaced by Cammerton in Germany, as some of the newest and most famous organs of the present time testify”.11 In this new system, the Chorton was at A+1 and the Cammerton at A-1.

Mühlhausen 1707-1708

This pitch difference of a major second between Chorton and Cammerton can be seen in two cantatas with recorder from Bach’s time in Mühlhausen. In BWV 106, only the recorders are in Cammerton F. All the other parts are notated in Chorton E♭. In BWV 71, the recorders, oboes, bassoon and cello are notated in Cammerton D and the other parts in Chorton C.

Weimar 1708-1717

In Weimar, no less than three different pitch relations can be found in the original sources: a major second, a minor third and no pitch difference at all. The evidence strongly suggests that the organ in Weimar was at Chorton A+1.12

When looking at the Weimar cantatas with woodwinds in general, an interesting pattern emerges13. Whenever Bach writes Oboe or Faggotto, in the Italian way, the pitch difference with the other parts is a major second. However, when he writes Hautbois or Basson, in the French way, the difference is a minor third. This points to the use of two different Cammertons in Weimar, namely that of hoch-Cammerton at A-1,14 and tief-Cammerton at A-2,15 resulting in the given pitch relations when Chorton is at A+1. Most of the cantatas with recorder have a pitch difference of a minor third.

In BWV 208, all the parts are in Cammerton F. In BWV 182, the recorder is notated in tief-Cammerton B♭and all the other parts in Chorton G. In BWV 152, the recorder, oboe, and viola d’amour are notated in Cammerton g and the other parts in Chorton e. Although there is no original source for BWV 161, later copies suggest that the recorders were in Cammerton E♭and the other parts in Chorton C.16

BWV 208 seems to be the exception, with all the parts at the same pitch. Most likely, this cantata was performed at a different location, with all instruments at tief-Cammerton.17 BWV 63, a Weimar cantata without recorders but with oboes, shows the same phenomenon.

Cöthen 1717-1723

The original sources of Bach’s music from this time show no signs of different pitch relations. Since there was no need for church music at the calvinistic court in Cöthen,18 Bach focused on chamber music. The performing pitch in Cöthen was rather tief-Cammerton (A-2 or A-1½) than hoch-Cammerton (A-1), as can be deducted from the vocal parts from this time.19 Since they are higher than most of Bach’s other vocal works, it seems that they were intended to be performed at a lower pitch. Also, “several of Bach’s principals at Cöthen had come from Berlin after Friedrich Wilhelm fired his band in 1713”,20 where the performing pitch had been tief-Cammerton. Three decades later, when Quantz had entered the court of Frederick the Great (1712-1786), tief-Cammerton was still the performing pitch in Berlin. Quantz’ sound ideal on the traverso was best reflected by this lower pitch, as he favored a “dicken, runden, männlichen, doch dabei angenehmen Ton”.21

Leipzig 1723-1750

In Leipzig, we know from Bach’s predecessor Kuhnau that both the organs in the Thomas- and Nicolaikirchen were at Chorton A+1,22 and that almost from the moment he began to take over the direction of church music, he “eliminated the use of Chorton and introduced Cammerton, which is a major second or a minor third lower, depending on which is most convenient.”23 So, in Leipzig, the organ transposed instead of the winds.

Bach’s use of tief-Cammerton and hoch-Cammerton in Leipzig can be seen in the two versions of the Magnificat BWV 243. The first version from 1723 with two recorders is in E♭major and the second version from 1732-1735 with two transverse flutes is in D major, whereas Chorton C remained stable in both versions.24 An E♭in tief-Cammerton is the same as a D in hoch-Cammerton. Perhaps, Bach was forced to revise the Magnificat because the tief-Cammerton woodwinds were no longer available for the second performance in the 1730’s.

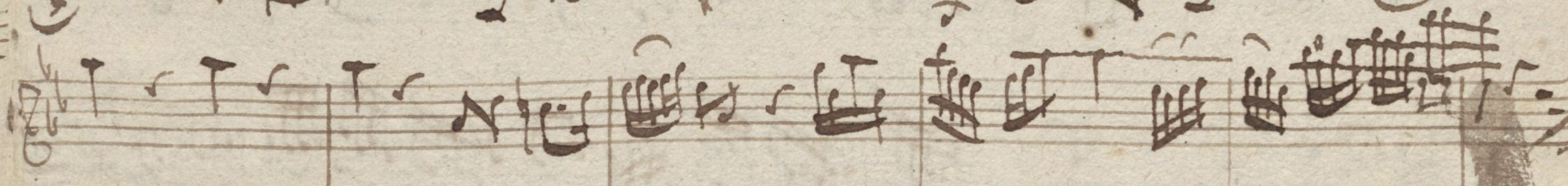

BWV 182 Himmelskönig, sei willkommen was reperformed in Leipzig in Cammerton G (and not in B♭as in Weimar). This forced Bach to rewrite the recorder part, since the transposition of a minor third down meant that the lowest notes from the Weimar version did not fit on the instrument anymore. This can clearly be seen in e.g. bars 5 and 6 from the aria Leget euch dem Heiland unter.25 The American conductor and musicologist Joshua Rifkin (1944) wrote that “we might ask if Bach did not in fact have it (the Leipzig version of BWV 182) perform on the transverse flute”.26 I do not agree with him on this point, because even though he is right that the new part was written in the atypical treble clef, the part clearly says Flauto. Also, if the part had been played on the traverso, the mentioned alterations to the part would not have been necessary, since the traverso easily plays down to e1, whereas the recorder does not.

BWV 161 Komm, du süße Todesstunde has a Leipzig version in which the two recorders are replaced by two transverse flutes. This second version is in Cammerton C, making it sound a whole tone lower than in Weimar, just like the Leipzig version of BWV 182.27

Tonalities

The tonalities Bach used most often for the traverso are, in decreasing order: D major, G major, B minor, E minor, A major, F♯minor, E major and D minor.28 D major is the best tonality, since the traverso itself is in D. The more fork-fingerings the tonality has, the more challenging it is to play strongly. Fork-fingerings are naturally weak notes on the instrument, caused by the need for opening a hole and closing one or two holes below it to create the right pitch. On the traverso, these weak notes are e.g. g♯, f and b♭. The best tonalities thus contain the fewest fork-fingerings, but at the same time, the stronger and weaker notes on the instrument give each tonality a different color.

Bach’s most used tonalities for the recorder in f1 are, again in decreasing order: F major, B♭major, G minor, C major, D minor and G major.29 Since the recorder has a different root note than the traverso, the fork-fingerings appear on different notes, resulting in other good tonalities. One could say that keys with sharps are generally better on the traverso, whereas keys with flats are better on the recorder. On recorders with a different root note, different tonalities will work better.

Tessitura

The range Bach uses for the traverso is d1-a3; the same range as Quantz gives in his fingering chart.30 Whereas g3 is necessary in fourteen of Bach’s works,31 a3 only appears in the Partita BWV 1013 for solo flute as the climax of the first movement. Since the a3 is needed three times in BWV 8.1 (also in stepwise movement), I am again unconvinced that this piece was originally meant for the traverso. Not to mention the frequent need for g♯3 in the same cantata; a note Bach never wrote anywhere else for the traverso. I believe that for this reason, Bach rewrote BWV 8 in D major for the performance in 1746/47. In this key, the traverso part works perfectly well, with g3 as the highest note.

The effective range Bach used for the Flauto is f1-a3, making an alto recorder in f1 the standard instrument for his compositions. Bach only asks for an a3 in the 2nd and 8th movement of the first version of BWV 182 and in the 1st movement of the Leipzig version of BWV 18. In most works, g3 is the highest note. Even though most fingering charts from the time go until this g3, Majer’s fingering chart from 1732 goes all the way until b3.32 Telemann even writes a c4 in the 3rd movement of the F major sonata from Der getreue Music-Meister.33

The recorder range is different in each of the three cantatas with flauto piccolo. BWV 96, with a sounding range of f2-f4, should be performed on a sopranino recorder (a recorder in f2). BWV 103 has a sounding range of e2-f♯4 and should be played on a recorder in d2 or sixth flute. On this flute, the f♯4 is as high as the a3 on the recorder in f1. Therefore, an excellent instrument and a skillful player is needed. As discussed, BWV 8 should be performed on a recorder in a1 or third flute.

A few thoughts on the f♯3 on the recorder in Bach’s works

The f♯3 on a recorder in f1 is a challenging note, because it is almost always too sharp. The modern solution for this problem is to lower its pitch by covering the bell of the instrument with one’s knee. In historical fingering charts however, this technique has not been mentioned. Covering the bell of the recorder is also an impractical technique for the player, especially in faster movements. On this topic, I share the view of the British flutist and musicologist Edgar Hunt (1909-2006): “Sounds produced by stopping the end of the recorder again are, I think, unlikely to have been used in the eighteenth century in the formal atmosphere of a court orchestra: they seem more suited to the relaxed style of today."34 To me too, this technique feels awkward and unconvincing when performing works by Bach.

In my experience, Majer’s fingering for the f♯3 (ø13457) is too sharp on alto recorders in A-1. On alto recorders in A-2 however, the fingering works much better, if gently played. The following table shows in which of Bach’s compositions an f♯3 is required (the given ranges are as notated in the original sources):

| BWV | Title | Rec. 1 | Rec. 2 | Rec. 3 | f♯ |

Origin |

| 25 | Es ist nicht gesundes an meinem Leibe | g1-g3 | Yes | Leipzig, 1723 | ||

| g1-e3 | No | |||||

|

|

f1-d3 | No | ||||

| 161 | Komm, du süße Todesstunde | g1-g3 | Yes | Weimar, 1716 | ||

| f1-g3 | No | |||||

| 182 | Himmelskönig, sei willkommen | g1-a3 | Yes | Weimar, 1714 | ||

| 1049 | Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 | g1-g3 | Yes | Cöthen, 1721 | ||

| f1-g3 | No |

As discussed earlier, the recorders in BWV 161 were pitched in tief-Cammerton. Given that, in my experience, Majer’s suggested fingering works better on recorders in A-2, I believe that it can be used for the high f♯'s in the first recorder part. The necessary trill on the f♯3 in the 5th movement can be played by fingering g3 as ø1346 (as Majer suggests), adding 5 and 7 for the trill. Since the first recorder part of BWV 161 does not descend below g1, it has been suggested that it could have been played on a recorder in g1,35 transposing down a major second. This theory allows the f♯3 to be played as a simple e3 (ø1245). However, this is not a practical solution, since it would result in uncomfortable fork-fingerings (as if playing the 5th movement in F minor). Majer’s fingering can also be used in BWV 182, since it was written for a recorder in A-2 as well.

BWV 25 was written in Leipzig and in C major. An original transposed organ part in B♭major shows that the pitch relation between Chorton and Cammerton was a major second.36 The recorders were thus pitched at A-1, and not in A-2 as in BWV 161 and 182. As mentioned, Majer’s fingering for f♯3 would likely have been too sharp on these higher recorders. Instead, the use of an alto recorder in g1 for the first part would work well, allowing the performer to finger the 3rd movement in the pleasant key of F major (and playing the f♯3 as an e3).

As mentioned above, BWV 1049 (composed in Cöthen) was most likely written to be performed in tief-Cammerton (A-2), allowing the use of Majer’s fingering. Playing the first recorder part on an alto in g1 would be practical in performances of BWV 1049 at hoch-Cammerton (A-1), fingering the piece in F major. Thus, the technique of covering the bell of the recorder is not necessary when Bach's music is played in its historical pitch. In my opinion, either Majer’s fingering or the use of a g-alto offers a historical solution.

Flutes in Bach’s orchestration

Compositions by Bach including only one recorder are quite rare. Apart from the flauto piccolo cantatas, only BWV 152, 182 and 1047 ask for a single recorder. Much more often, there is a need for two recorders. In BWV 25, 122 and 175, all written in Leipzig, Bach makes use of three recorders. In the last movement of BWV 46, Bach doubles the two recorder parts in the two oboe da caccias, making a total of four recorders. In BWV 244, the recorder parts are written in both the doubled 1st and 2nd violin parts, but this seems to be a practical issue rather than an invitation to play the movement O Schmerz with four recorders.37

Not counting the solo sonatas, Bach still wrote slightly more works for one traverso than for two. Three transverse flutes are asked for in BWV 206, and BWV 244 has four flutes. Bach only combined the recorder and traverso in the same composition in BWV 8, 96, 180, 244 and the first version of 249,38 but never in the same movement.

The arias in three parts (traverso, voice and continuo) are always written for a single traverso. Bach’s use of two transverse flutes in unison in Ich folge dir gleichfalls from BWV 245 is the only exception. However, the same type of arias for recorder are more often to be played in unison, namely in the 5th movements of BWV 39 and 119,39 and in the aria Ach, Herr, lehre uns bedenken from BWV 106. Leget euch dem Heiland unter from BWV 182 and the flauto piccolo aria Kein Arzt ist außer dir zu finden from BWV 103 are the exceptions.